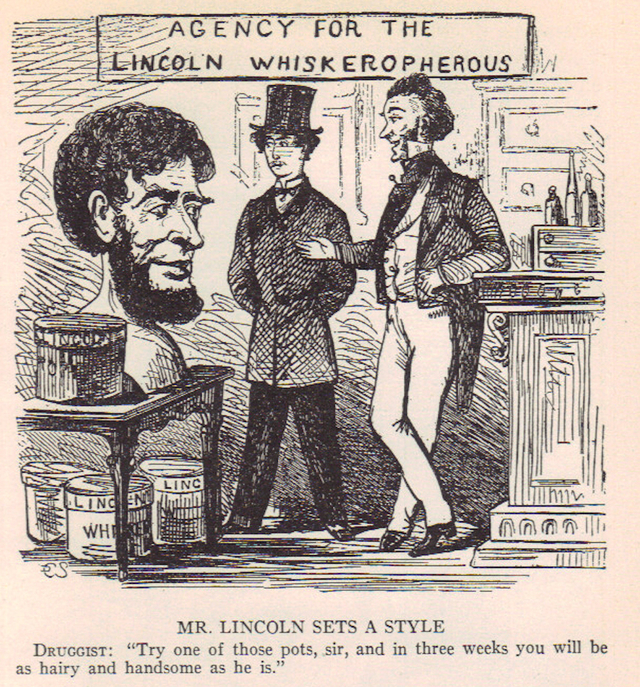

The Beard That Wasn’t: Abe Lincoln’s Whiskers

It’s a familiar story. On October 18, 1860, the Hon. Abraham Lincoln of Springfield, Illinois—Republican nominee for President of the United States—received a letter from eleven-year-old Grace Bedell, of Westfield, New York. Though a confirmed Lincoln supporter herself, Bedell worried that others, including one or more of her brothers, might need convincing. As a remedy, she suggested the candidate grow facial hair. “[I]f you let your whiskers grow,” Bedell told Lincoln, “I will try and get [my brothers] to vote for you.” Sweetening the proposition, Bedell added that “all the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husbands to vote for you and then you would be President.” A bold child, Bedell closed by asking Lincoln to “answer this letter right off.”

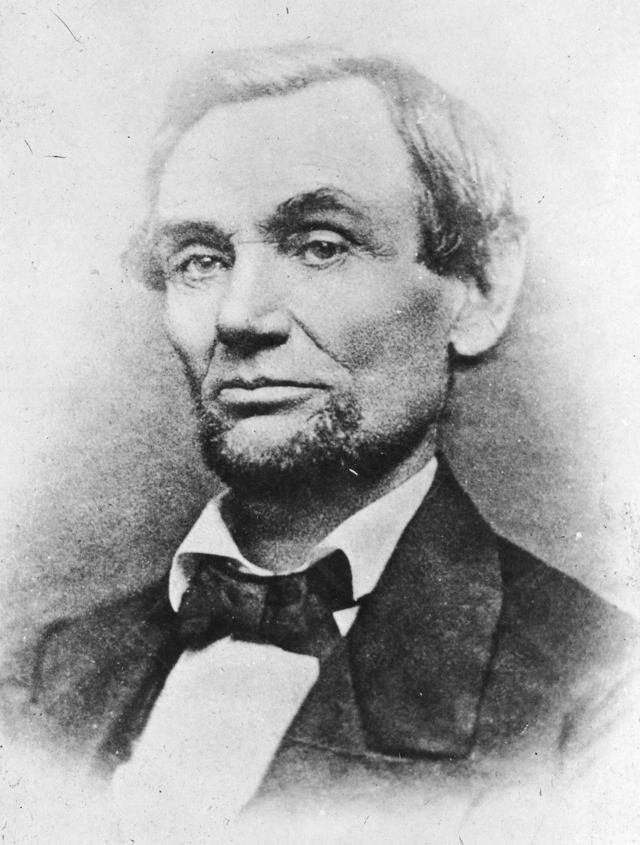

And so he did. Replying the following day, Lincoln thanked Bedell for her letter but questioned her advice. Having “never worn any” whiskers, Lincoln wondered, “do you not think people would call it a silly affect[at]ion if I were to begin it now?” Although Bedell did not respond, the future president resolved the question to his own satisfaction, commencing his life as a bewhiskered statesman in early November, shortly after sitting for his last clean-shaven portrait. By the fifteenth of that month, Lincoln’s facial hair was long enough to elicit comments. His friends, according to New York Herald writer Henry Villard, teased him for “putting on [h]airs.” Later than month, when Lincoln sat for Chicago photographer Samuel G. Alschuler, he wore the beginnings of a respectable goatee. And by February 1861, when Lincoln departed Illinois for the capital, he wore what modern Americans would call a ‘wreath beard.’

The first image of Lincoln with whiskers. Photograph by Samuel G. Alschuler, Nov. 25, 1860. Library of Congress

It was an extraordinary transformation. For the first and only time in American history, a president-elect dramatically changed his personal appearance between his election and inauguration. In the process, he rendered the vital visual paraphernalia of democratic politics—the prints, campaign pamphlets, and cartes de visite that cemented ties between politicians and the electorate—irrelevant. Why would Lincoln take such a potentially-alienating risk? What did facial hair do for Abraham Lincoln that being clean-shaven did not?

Lincoln’s army of biographers have offered a number of explanations. David Herbert Donald, for instance, suggested that Lincoln’s beard lent the president-elect “a more authoritative and elderly … visage.” William C. Harris speculated that it was intended “to give his face a more dignified and mature look befitting a national leader.” And Harold Holzer—the most prolific authority on Lincoln’s beard—claimed that the president-elect grew his facial hair in an effort to discard his “image as frontier railsplitter,” thus transforming “Honest Abe into Father Abraham.” Lincoln’s beard, in other words, lent him patriarchal gravitas. In the face of widespread doubt about his ability to manage the secession crisis, the president-elect at least “looked up to the job.”

There are only two problems with this argument. First, Lincoln didn’t have a beard. He had whiskers—an enormously important distinction in mid-nineteenth century America. And second, Lincoln’s whiskers didn’t signify maturity, statesmanship, or gravitas, but rather urbanity: civilized, metropolitan grace. They were more Beau Brummell than John Brown, intended and interpreted as a rebuttal to claims of rustic rudeness, rather than those of dithering impotence.

This is not to suggest that Lincoln’s whiskers were wholly without patriarchal connotations. Facial hair was in a state of symbolic flux at the outset of the Civil War—a state of affairs the savvy sixteenth president likely understood and exploited. But in the months between November 1860 and March 1861, Lincoln’s whiskers were seen—first and foremost—as an effort at fashionable urbanity.

Imagine yourself in Lincoln’s enormous shoes. You are a tall, gangly man with lantern cheeks, elephantine ears, and asymmetrical lips—an ugly drink of water, even by the standards of an unsightly era in men’s appearance.

It is December 1860. You have just been elected President of the United States. Politicians in South Carolina are openly threatening to leave the Union. There are dire rumblings throughout the Deep South. In your worst nightmares, you imagine Missouri and Kentucky—even Maryland and Delaware—severing their ties to the government in Washington. Disunion, civil war, bloodshed on land and sea—these are suddenly real and present dangers.

And the worst part? Nothing in your experience—not your time in the Illinois state legislature, your unsuccessful bid for the U.S. Senate, your single term in the U.S. House of Representatives, even your log cabin childhood or your career as a frontier lawyer—nothing has prepared you for the job you’re about to assume.

So what are you going to do? Are you going to follow the stern example of President Andrew Jackson, who, during an earlier moment of secessionist panic, reportedly threatened to hang the first rebel he could get his hands on from the first tree he could find?

No. You are going to grow whiskers. And to further inspire awe in your opponents, you are going to tell everyone that you did so on the advice of an eleven-year-old girl.

This is the argument that some of the finest, most-careful of Lincoln’s many biographers have made about his whiskers. And, strange as it is, their argument rings true because it corresponds with our image of Lincoln as the Alpha and Omega of American civic religion: a marble man of strength and wisdom.

But in the months before his inauguration, Lincoln was anything but Abrahamic—let alone Christ-like. An untested rube who won a mere forty-percent of the popular vote in the 1860 election, Lincoln was widely believed to lack the experience and authority that the secession crisis demanded. Why, then, was he at such pains to emphasize Grace Bedell’s role in his changed appearance? Why did he make a point of stopping in Bedell’s tiny hometown of Westfield, New York—explaining to the assembled crowd that “it was partly on her advice that he … let his whiskers grow”? Why, in full view of some of the country’s leading journalists, would he step down from his Washington-bound train and greet his correspondent with a much-publicized kiss?

As political theater, the incident was inspired. It demonstrated Lincoln’s attentiveness to correspondence, his concern for the disenfranchised, and his fatherly tenderness—all esteemed virtues in the nineteenth-century United States. But while the Bedell story may have provided a laudably paternal explanation for Lincoln’s decision to grow a beard, the choice hardly resounded with patriarchal authority. Little about the incident suggested Abrahamic fortitude. Among a number of commentators, in fact, the Bedell story actually served to undermine his gravitas. A New York Herald writer, for instance, characterized Bedell’s letter as “foolish” and denounced Lincoln’s behavior as “beneath the dignity of the office to which he has been elected.” Contrasting Lincoln with Confederate president Jefferson Davis, the Herald writer found the former wanting. Unlike Lincoln, Davis had traveled from Mississippi to Alabama without having “told any stories, cracked any jokes, [or] asked the advice of the young women about his whiskers.”

He was not without alternative explanations for his changed appearance. In October 1860, a group of die-hard Republicans wrote to their candidate in a state of distress. After carefully considering the daguerreotype images of Lincoln they wore on their lapels, they arrived at “the candid determination” that he would be “improved in appearance, provided you would cultivate whiskers.” Earnest supplicants, the ‘True Republicans,’ as they called themselves, testified to Lincoln’s power in a way that Bedell’s precocious familiarity did not. If Lincoln had wanted to portray himself as a master of men, this surely would have offered a more flattering explanation for his decision. But instead he singled out Bedell. Clearly, then, Lincoln’s whiskers—and the story he told about them—were intended to communicate something other than Abrahamic authority.

What Lincoln’s facial hair was meant to convey becomes clearer when we consider the language that the president-elect and his contemporaries used to describe it. While we moderns presume to call Lincoln’s facial hair a beard—“the most famous beard in the history of the world,” according to The New York Times’ Adam Goodheart—Civil War-era Americans would have recognized the president-elect’s facial hair for what it was: a fine set of whiskers. In fact, a thorough search of a leading digital newspaper database reveals that between November 1860 and March 1861, only two of dozens of commentators used the word ‘beard’ to describe Lincoln’s appearance.

This was not coincidental. The words ‘beard’ and ‘whiskers’ connoted distinctive styles in mid-nineteenth century America—and contemporaries used the words differently than we do. The word ‘whiskers’ typically referred not only to bushy cheek growths—to massive sideburns and muttonchops, as it does in the present—but to what we would call a ‘wreath beard’ as well: to facial hair configurations that met beneath the jaw. Edgar Allan Poe, for example, described one fellow writer as having “[t]hick whiskers meeting under the chin,” and another whose “hair and whiskers are dark, the latter meeting voluminously beneath the chin.” One might even use the word whisker to refer to what we would call a moustache. Writer Edward L. Carey, for instance, referred to a character with a “whisker on [his] upper lip” in a story entitled “The Young Artist.”

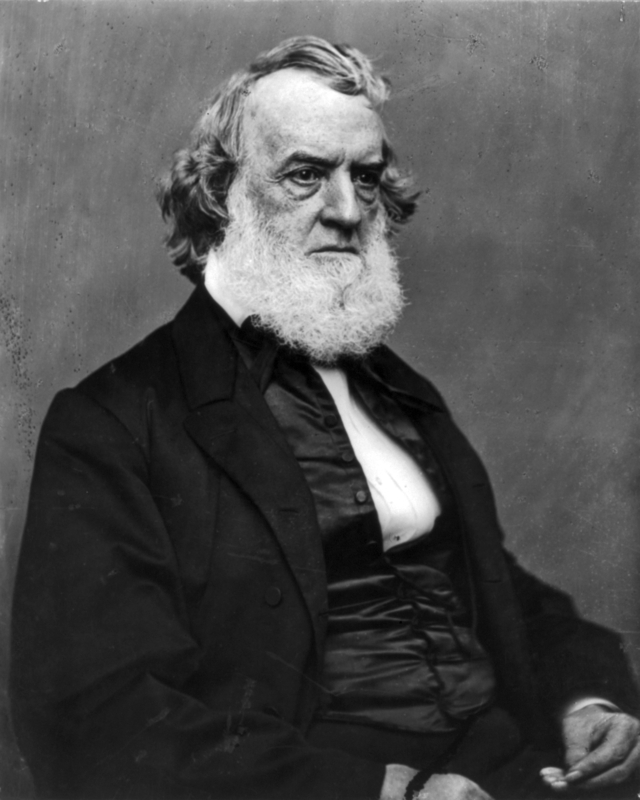

‘Beards,’ on the other hand, were more unruly affairs. In an article in the American Phrenological Journal entitled “Wearing the Beard,” for instance, the anonymous F.W.E. instructed beard-wearers that, contrary to the practice of bewhiskered men, “Thou shalt not cut it off at all, but let it grow. Let it grow, all of it, as long as it will.” What often distinguished beards from whiskers, then, was neither facial real-estate nor the length of one’s hair—one might wear a short, untamed beard-in-the-making or a long, carefully-sculpted set of whiskers—but rather one’s relationship to the work of men’s grooming. Hairy men who continued to visit the barber, trim their mustaches, or wax their locks wore whiskers; men who let their facial hair grow unrestrained sported beards.

A survey of these words in the pages of Godey’s Lady’s Book—antebellum America’s best-selling periodical—indicates why the distinction mattered. While whiskers appeared on the faces of European noblemen, professional military men, and dashing young dandies, beards were most closely associated with Biblical patriarchs, unkempt gold prospectors, and messianic radicals.

A fine beard in the nineteenth-century sense. According to a Mr. Dicey in MacMillan’s Magazine for May 1862, U. S. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wore “a long white beard and a stupendous white wig.” Wikimedia Commons

Prince Albert sported the former—a style that signified a refined and restrained ideal of male comportment. John Brown, by contrast, wore the latter, harkening back to a militant, even Biblical, vision of manhood. Thus, it was the beard, and not whiskers, that connoted the kinds of Abrahamic virtues that Lincoln biographers have discerned in the president’s facial hair—the fearsome strength and gravitas he was so apparently lacking.

What, then, did contemporaries make of Lincoln’s whiskers? Even the most complimentary assessments of his new appearance did little to boost his patriarchal profile. “Old Abe,” wrote an enthusiastic correspondent for the Lexington, Illinois Globe, “is commencing to raise a beautiful pair of whiskers, and looks younger than usual.” The Democratic Albany Argus, claimed that “[t]he country does not want wisdom or courage in its Executive, but beauty. … Lincoln knows it, and he is up to the crisis!” And the New York Herald’s Henry Villard repeated the joke that “Abe is putting on [h]airs.”’

Admittedly, the last two comments originated with Lincoln’s political opponents—men with good reason to mock the president-elect’s appearance. But even his most enthusiastic supporters tended to describe his whiskers in terms that diminished rather than augmented his stature. One writer, for instance, suggested that Lincoln’s facial hair gave him “a more sober and serene outlook … like a serious farmer with crops to look after, or a church sexton in charge of grave affairs.” It was no doubt earnest praise but hardly an august comparison for a man about to assume the presidency, let alone the mantle of Biblical patriarchy.

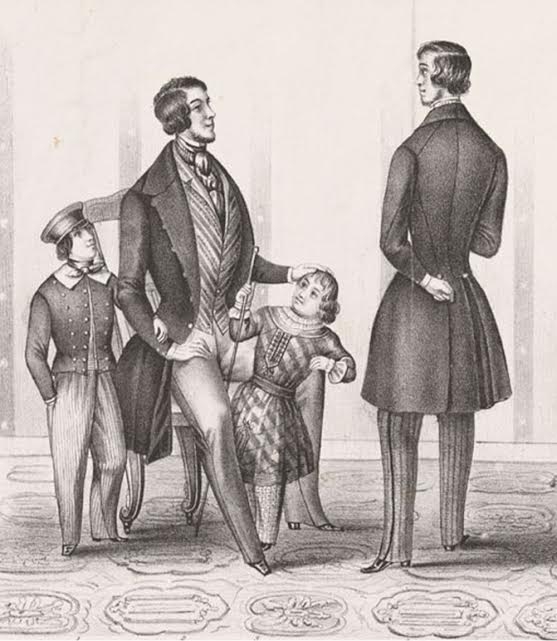

Whiskers as tokens of urbane refinement: detail of John Taylor, “Philadelphia Fashions, Fall & Winter 1845, by Samuel A. Ward & Asahel F. Ward,” lithograph. Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Rather, Lincoln’s whiskers were meant to signify urbanity and refinement. Adopting a fashionable style of grooming—the wreath of whiskers that had been a fixture of men’s fashion for decades—Lincoln offered a visual counterpoint to persistent barbs about his rough manners, rural upbringing, and rustic sense of humor. Holzer, then, was at least partly right about the meaning of Lincoln’s whiskers. He was, in fact, shedding the campaign image of the frontier railsplitter. But instead of adopting the look of a firm patriarch (or even a stern sexton), he was cultivating the appearance of a man of the world: a person of humble origins but hard-earned cultural capital.

Bewhiskered family men: detail of Edward Williams Clay, “Shankland’s American Fashions for the Fall & Winter of 1854 & 5,” lithograph. Library of Congress

He had good reason to do so. Since assuming the national stage, Lincoln had been dogged by doubts about his social graces. An article from the Columbus, Ohio Crisis, for instance, lampooned his ignorance of classical languages, while informing polite readers that Lincoln had only recently “abstained from facetiously designating hotel napkins as towels.” And one contemporary, recalling an encounter between the former Secretary of the Navy George Bancroft and Lincoln noted a “most striking” contrast between the two: “the one courtly and precise in his every word and gesture, with the air of a trans-Atlantic statesman; the other bluff and awkward, his every utterance an apology for his ignorance of metropolitan manners and customs.” Eager to dispel these aspersions—especially in light of unfavorable comparisons between himself and the stately Jefferson Davis—Lincoln grew fashionable whiskers, not a patriarchal beard.

What does this story tell us about Old Abe Lincoln? Besides the obvious—that the “most famous beard in American history” was not a beard at all—it reveals something about the nature of power in Civil War-era America. Taking command of a sinking ship of state and confronted with dire questions about his fitness for office, Abraham Lincoln chose a set of symbols that emphasized urbanity over more obvious emblems of authority. Calling on an old set of ideas about gentility and power, the president-elect claimed, in effect, that the right to rule hinged as much on politeness as on patriarchal strength or the imprimatur of the people. It’s a strange story, to be sure. But it reminds us of the extraordinary currency of symbols like these: that faced with national dissolution and civil war, Lincoln sought the urbane sophistication required for his job in, of all places, his hair.