Sürgün

Feodosiya, Crimean Peninsula

1944

A knock broke through the veil of Ayshe’s sleep. Or did it? Ayshe was not sure what she’d heard. But she was awake now, and something had stirred her. Usually there were only dogs barking at this time of night, or, on occasion, drunken fisherfolk shouting down at the tiny port. These heavy hours, at the very start of a new day, were so thick with darkness that they tired anyone who tried to move within them. Yet something had been moving. Ayshe rolled to her side and inched upward, as if freeing her ears to the open air would allow her to hear better.

Nothing. Her family slept on, bundled in blankets and nestled on the thick top of the earthen oven that warmed their dacha. Her mother lay below on her cot on the ground, with her strong arms lying at her sides. A rhythmic snore escaped her mouth, which gaped open to show the few remaining teeth in her gums.

Ayshe was upright and more awake now. She was sure something from outside had disturbed her sleep. There was a tension in the night: the sense of a being moving silently outside. She shivered, and as lightly as she could without disturbing her brother and sister, pulled the wool shawl that served as their pillow from under their heads and up around her slender shoulders. She looked about the room.

Another knock. This time it was loud and uncompromising. It was not a knock to wake up the house, Ayshe thought, but a knock to warn of imminent entry. Before Ayshe’s astonished eyes the door burst open, revealing a black silhouette framed against the moonlight. Ayshe cowered in the corner, and tried to remember whether any weapons were within reach. She thought of the iron firerod, which she and her mother used to turn the embers in the oven that warmed their home. It was on the other side of the room, near her mother’s cot. If she could just slip down from the oven somehow, unnoticed…

“People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs,” boomed the voice. Ayshe jumped. People’s what? she thought. It sounded like a Soviet office. And this person was speaking Russian. Ayshe’s sister and brother were stirring, pushing back their blankets with alarm and blinking in confusion. Her mother’s rhythmic snoring had ceased, and she was looking up from her cot, bewildered by the black figure in the doorway.

“Who is there?” Ayshe asked in her Turkic tongue, more alert and ready to talk than her stunned mother or confused sister and brother. Part of her voice got lost in her throat.

“I am an officer of the NKVD,” replied the black silhouette, in Russian.

“The… NKVD?” Ayshe replied, this time in Russian. She was the only member of her family fluent enough to converse with the Russian troops, though her mother understood the language when it was spoken by others. The thought of the NKVD scorched Ayshe’s brain like a red coal. The Soviet police. One month ago Red Army troops had come to expel the Germans from the Crimean peninsula; she and her neighbors had welcomed them with relief. But soon the Soviets had installed the same checkpoints, and began asking for the same things as their predecessors; food, accommodation, women, and some people’s lives. The people of darker skin, or different features, like Ayshe and her family, were treated especially badly. Ayshe’s aunt had said that in a village near Sevastopol, the political center of Crimea, two families of Turk-Meskhetians had been brutally murdered by the Soviets. Ayshe knew her own people, Islamic and not Christian like the Russians, were held in similar regard to the Meskhetians. But in their homely dacha, in the village of her ancestors, she thought they were safe.

“You, as members of the Crimean Tartars, have been ordered to leave this, your place of residence, and the Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic of the Crimean Peninsula, immediately,” the voice continued.

Ayshe stared blankly. She felt her young brother, Musa, huddle next to her, and grip her arm.

“Leave… here?” she managed.

“To leave immediately,” restated the officer. “You have been found guilty of massive collaboration with Nazi troops, and partisanship against the Soviet Union and her Red Army.” Ayshe looked around at her small family, cowering before this demon-like figure, just as they had cowered before the Nazis at checkpoints around Feodosiya. Collaboration with the Germans?

“You shall be deported at once. Dress, pack your belongings. Your name will be called in the central rynok in twenty minutes, at a role call administered by NKVD officials. If your entire family is not present you will face immediate… punishment.” The black silhouette turned to leave. Ayshe saw the profile of his high forehead, remarkably calm and flat. She noticed his pointed khaki cap, the glint of the Soviet insignia, the fringe of an epaulet that danced on his shoulder as he turned. “Your number is 2/42. Do not forget it.” As he stepped heavily from the threshold his high black boots, polished like statues, glinted in the moonlight. He left the door gaping like a mouth open in fright. Musa began to quietly sob. Beside him, their sister Elgar was awake but silent.

“Mama?” said Ayshe, too astonished to know what else to do. “Mama? Did you hear that?” Her mother was moving out of her cot. “I heard,” she said.

“And what do you think?”

Ayshe and her mother’s eyes met across the room. Her mother’s gaze was uncertain. She looked both roused by fear and paralyzed by that same fear. Her eyes were lined with the hard-earned wisdom of having survived in a harsh reality, and Ayshe knew her mother’s pragmatism had kept her family safe until now. Eventually, her mother’s gaze fell from Ayshe’s. “Ayshe,” she said steadily, so that Ayshe was mystified by her sudden calm, “this is no time to talk. We must move.” Ayshe felt tears start in her eyes and a ball of anger clench in her throat. Her mother was already out of bed. She took a round candle from the floor beside her cot and crossed the small room to the earthen oven. There she opened the metal oven door, and held the candle to a still-burning ember. The wick sputtered and lit, and a delicate glow filled the room.

Just then, another figure stood in the doorway. Again, it was a large male, but this time he did not look like an officer. In the light of the candle Ayshe took in his khaki uniform; the buttoned cotton coat with a patch at the collar, the cotton trousers, the brown leather boots. His face was rigid beneath his cap, and he did not look at any one of them now lit by the candle flame but stared indifferently into the room. He held a rifle between his hands. The blade pointed up, over his shoulder, to the night sky outside. It was unmistakably visible, and real.

“Twenty minutes to roll call!” the soldier barked. Then he turned from the doorway and left, unblinking, with that same unfocused gaze, as though his eyes had not seen anything.

Ayshe’s mother was already rolling up the heaviest blanket from her cot into a tight bundle. Ayshe watched incredulously as her mother strode to the door and slammed it shut. Then she went to the shelves on the back wall, opposite the door, and pulled aside the muslin curtain which covered them. She took out a large chunk of cured meat—their biggest and only remaining piece of meat from last summer—and wrapped it in a muslin rag hanging on a nail from the lowest shelf. This she carried to the cot. She returned to the food shelves, and took down a smaller chunk of sala—the pig’s fat which filled them with energy—and a glass jar of pickled cucumbers, a smaller jar of pickled onions, and the large knobby end of a loaf of black bread. These she also brought to her cot, and placed them on the woolen blanket that was remaining. She returned to the food shelves, and collected more of the same.

Seeing Ayshe’s immobility, she snapped: “Get dressed.” Ayshe kept staring at her in disbelief.

“You’re… you’re going to do what he asked us to?”

“We must, Ayshe. Get moving. Wake up!” She barked this last order at Musa and Elgar, who were both peering around the room with moon-round faces. Their mother was charged, moving faster, on full alert. Musa sat up but Elgar remained partially hidden under the blankets.

“But why? This is crazy!” Ayshe shouted. Her mother paused between the food shelves and the bed. She had a small bottle of plum alcohol in her hand.

“They are Soviets. He was an officer of the secret police! They have wanted us gone from here for a long time, Ayshe.” Her jaw was taught, her face rigid. “The Russians in this town, I’ve heard them say it. ‘The Tartars take all the good land.’ ‘The Tartars will be deported.’ He was not joking. There was no humor in his voice tonight.”

“But why? It is a joke to say that we have collaborated with the Germans! Papa’s been fighting for the Red Army for four years now!” Her mother, who had returned to wrapping the meat, sala, pickles, bread, and alcohol tightly in the wool blanket, turned back to Ayshe. Her eyes flashed with anger. Even in the half-light Ayshe could see them glinting, like the beady eyes of a wolf.

“The Meskhetians—the Umerovs by Sevastopol—the last things they saw were the rifles of the Soviets. This is what happens to people who stay in the wrong place. Get dressed.” Her irises were so dark they seemed to merge with her pupils now, so that each eye was a black circle framed by white. “We must believe he said the truth. If he said the truth, that means we now have only five minutes to get ready. Ayshe, do what I ask. Get dressed, in your warmest winter clothes. Put on your valenki.”

“But…” Ayshe couldn’t go on, her voice was dead in her throat. For a minute, her mother softened. Ayshe saw in the light of the candle that her mother was just as scared as she. The whites of her eyes were even larger, and she was breathing rapidly in her upper chest. Her long, graying hair frizzed out from her plaits and framed her brown face. Her wide, squashed nose and almond eyes were so familiar to Ayshe she could conjure them in her sleep. The creases around her eyes—from laughing, but also from squinting too long in the hot sun while she worked their shared farm—gave Ayshe a sense of both hope and the unstoppable passing of time.

“I know it’s spring,” her mother responded. “It’s not winter anymore. But we need to be prepared. I have heard… some things, about where they plan to take us. Get your valenki, and your heavy woolen shawl, and your heaviest winter dress. Put them on over your bed clothes. Keep your bed shawl on.” Ayshe still didn’t move. “Now, Ayshe!” she snapped. “Then help Musa and Elgar into their clothes.”

Ayshe refused to move—until she heard the rifle shot. The shot must have been a short way off—perhaps at the top of the lane, on the hill overlooking Feodosiya. The single clap silenced the room, and what seemed like the world outside. In the ringing silence, a dog barked once. Then the quiet resumed.

Their mother turned to Musa, who was still clinging to Ayshe. Musa was only seven, but he felt the power of that gun shot. He had understood the tension in the room and he had watched breathlessly as the darkened figures had loomed in the doorway and barked out evil-sounding phrases. He sniveled as his mother turned towards him and he reached out his arms for her. But she did not pick him up. “Musa,” his mother said, as though the gunshot had made her even calmer, and more rational. “This is a good game for you. Get down from the bed, and pick out your strongest trousers and your longjohns and your thickest wool coat. Put those on—”

“On top of my bed clothes, mama?” he managed to say. Musa did not know what the Soviets were, or how they were different from the Germans. He was in his second year of the Tartary school and had taken poorly to the Russian language. But his teachers said that he was a perceptive and willing child.

“Yes, on top of your bed clothes. Then take your valenki, your best winter boots, from the outside shed and bring them to Ayshe. Do it as fast as you possibly can—it’s a race.” Without hesitation, Musa jumped from the bed and ran to the wooden chest by the back door. He began to tear out clothing piece by piece, searching for the winter clothes stored at the bottom.

Ayshe managed to slide to the dirt floor. The feel of its reassuring coolness on her foot soles sturdied her. She looked at Elgar, who was lying half-hidden in the bed, still shaking beneath the blankets. Elgar, she thought, would need a lot of help. She was nine, a year and a half older than Musa, but so timid and shy she was almost always silent. Though they were separated by eight years, Ayshe felt very close to her little sister. While her mother would do everything to help Musa, the only boy in her family, Ayshe knew she must protect Elgar. If there was something brutal outside their dacha, making its way through her town like a tornado, Ayshe would ready herself to face it.

Almost all of the houses along her lane had been roused. Frantic families, lone adults, and Soviet soldiers and officers were crossing back and forth. The soldiers moved up and down the lane, barking orders, occasionally butting against one another in play. Their odd, shrill laughs sounded deliberately cruel alongside the despairing shouts of Ayshe’s neighbors. She heard voices she recognized. “Khan! Khan! Where is Khan?!” called a young male voice two doors away, and she knew that must be Mameti Jemilev, looking for his dog. Perhaps he hoped to bring Khan with him. Ayshe thought again, with a chill, of the gunshot. It was not clear what the source, or victim, of the shot had been. Her stomach tightened with the strangeness of it all. In the bustling, teeming lane, the scene seemed almost friendly. Except it was nighttime, and panic was twisting the air.

In front of Ayshe’s doorstep, a family of three had stopped to rest with two large bundles of clothing. Their faces were strained and their skin pallid against the darkness. They stood, breathing heavily. Ayshe recognized them as her people, Tartars.

“Where have you come from?” Ayshe addressed them in Tartary.

“South of the old port,” replied the woman, referring to the poorest quarter of Feodosiya, half a mile away. Her long hair was undone, and her silk shawl had fallen from her head to expose a lined brow. Her head looked naked and vulnerable without her shawl, but she did not bother to reset the headdress. Her two male children stared helplessly at Ayshe. The boys had bare feet, and one was in only his bed clothes. Ayshe thought they must have been nearly teens, but they looked tiny and frail beside their heavy loads.

“Will you make it with those bundles?” Ayshe asked.

“We have to,” replied the woman. “Our clothing, our food, without their father…” And without further explanation, she hoisted one of the bundles onto her shoulder, and instructed the children to pick up the other. They did so, one on each end, their faces pinched tight.

The first petals of spring were swirling from the trees. A late night breeze, stolen from the ocean, lifted the woolen hem of Ayshe’s dress as she stood on the threshold. She shivered despite the warm air. In the dacha behind her, her mother gathered their last possessions and pulled final pieces of clothing onto her children. Ayshe stood watching the world for a short twenty seconds that felt like two hours. She could see the big, thick-soled impressions of a hundred heavy boots that had churned up the sandy lane before her. Another family—a large one this time—was making its way towards Feodosiya’s center. Five scantily dressed children were trailing behind a young woman and her two elderly parents. The woman had a small baby clasped in her arms. Ayshe thought she recognized them as her neighbors from the next lane over, the Chobanovs. They did not even look her way as they passed. Perhaps they didn’t recognize her, Ayshe thought. Feodosiya was a town of thousands.

But in the lanes surrounding the town center like this one, everyone knew their neighbors well. Why hadn’t the Chobanovs acknowledged her?

It’s true that Ayshe and her family were poorer than many other Tartars of their town, and most certainly poorer than the Russians. They lived only on the food they grew, foraged and sometimes sold, and they made clothing from the wool of their small shared farm. But despite their poverty, Ayshe had always loved living outside of Feodosiya’s cramped central zone. They had space for a small garden and were closer to the land beyond the town’s limits, which they worked during the day. She could walk to the market for family necessities, or down to the seaport for scraps of fish leftover from the day’s catch, and then be home again in ten minutes. In the center proper, families often crowded together in one building. Since the war had begun, many families shared one room, for security as much as for pooled resources. So many men and women had been taken away by Stalin to work in factories or serve in the war, and such high numbers of them had been lost at the Battle of Kiev. Even more were disappearing along the front, fighting the Germans. Ayshe still prayed for some news from her papa, who had been serving there for many months.

At the thought of her family, Ayshe turned back into the dacha. Her mother and siblings were dressed, loaded from head to foot in their heaviest winter gear. Already, Musa was complaining that he felt hot.

“It’s because we are inside Musa. Now, we must get going.” Ayshe’s mother hoisted one of the bundles to her shoulder. She had rolled it into a tight cylinder and tied it with thick twine, so it looked like a roll of blankets or clothing. Only Ayshe knew there was food inside. Ayshe picked up the second bundle, a felted wool cylinder comprised of the two heaviest blankets from their beds. Inside, they had placed small bottles of their homemade alcohol, and a clay tub with the resin of the Mastic tree. This resin was a powerful healer. The family extracted it from the tree and used it medicinally for wounds and internal pains. Ayshe’s mother brought it everywhere.

In the rush of pulling on clothing, Ayshe had thought to place the only sentimental item she owned into the pocket of her dress. It was a small, pressed flower, folded between thin, delicate paper. She had found this flower in a field outside their mosque the summer before. Its deep purple petals, so striking against the yellow-brown of the field, had caught her gaze. They looked mysterious somehow, as though a girl could be shallowed up by their rich dense color if she stared at them long enough. There, in the field, with the broken-down mosque behind her, and German troops rolling by in jeeps, Ayshe had felt this special flower might be a doorway into another land. At home she pressed it between the only paper she had—two thin sheets she had made by hand at school from the ground fibers of the flax plant. Now it sat, folded in her pocket, thin, delicate, and secret.

Ayshe hoisted the second bundle to her shoulder, took Elgar by her small hand, and left the dacha. “Should we close the door, mama?” Her mother’s face was the color of the grey ash left after burning the branches of the Mastic tree. “Yes, Ayshe,” she said. She had Musa’s hand in hers, and was already beginning to walk up the lane towards their town center. Ayshe let go of Elgar and reached behind her to pull the stout, wooden door of their home closed. She did not think this would be the last time. Even at seventeen, and even with a full education, Ayshe thought they would return.

A cacophony of voices was bubbling up from the main rynok of the town. As Ayshe and her family approached, Ayshe noticed it wasn’t the sort of drunken yelling of her townsfolk that she was used to, nor even the derisive laughter of the soldiers in the lane just now, but a frenzied howling, like the sound of fighting cats. As Ayshe strained to listen, she could separate out two sounds: a commanding shout that barked out intermittently, and a high-pitched response. Ayshe’s heart banged in her chest. She dropped Elgar’s grasp for a moment to draw her shawl closer, and her sweaty hand slipped from the woolen material.

Her small family trod onwards. In their valenki, the thick felt boots their mother had demanded they wear, their steps were labored and slow. Musa again complained of overheating. Elgar strode diligently onwards, saying nothing. Within a few minutes, they reached the edge of the square.

“This is a mistake!” Ayshe heard a single voice yelling now. It reverberated off the brown stone buildings and across the cobbled ground. “We’ve betrayed no-one!” There was a response from the other side—but quiet, too quiet for Ayshe to hear. It was drowned by a rhythmic sound that seemed to come from the far side of the square, through the loamy streets to the north: the stomping of men, the pulse of boots on earth. A chill danced up Ayshe’s back. It was the sound of marching. They were coming from the train station, she thought.

When Ayshe and her family entered the rynok proper they saw it was already full of people. Tartar families, like her own, stood huddled around the square’s two large Ash trees, or on the edge of the square with all the possessions they had managed—or thought—to grab in ten minutes: coats, scarves, candles, framed photographs of men missing in the war. One young girl clung uncertainly to a dining room chair. NKVD officers, like the one who had knocked on their own door, strode back and forth from one of the rynok’s main buildings, papers or loud speakers in hand. A handful of them were standing on a makeshift raised platform in the center of the square. An angry huddle of Tartars had gathered about them.

“Roll call for East Feodosiya, lane numbers 1 to 50, begins in three minutes!” boomed the voice of one of the officers. The small crowd cried out in response. Again, a single, high-pitched voice broke over the noise. “You must give us a reason for this! There has been no collaboration with the Germans! We suffered at their hands!” When the officers ignored this call, the man continued to cry, “Speak to me!”

“Everyone, stand back from the podium. Find your families. Group into numbers,” came the only response.

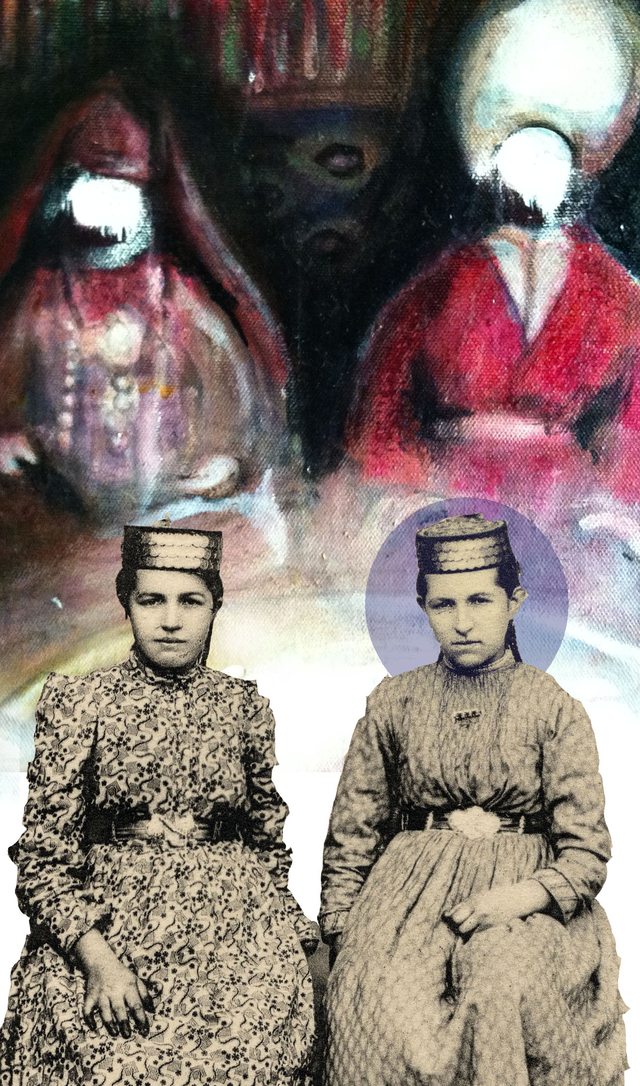

The cool detachment of the officers incensed the crowd and distracted it from the rumbling vibration of the approaching soldiers. As Ayshe scanned their faces, she realized she recognized many of these villagers. The dark hair, the high cheekbones. The karakol hats, rounded with short sides, which were perched on the male heads, the wool or silken shawls that covered the females. The long tunics on the men, the wide-skirted, full-length dresses on the women. They were all her own people. But they could not hear the soldiers coming. Ayshe sensed the military mass bearing down on the square. This, she thought, was why the officers were so calm and dismissive. At any moment the Red Army would come surging into the square, sweeping up dissenters and knocking over anyone who stood in its way. The soldiers would carry their ugly rifles at the ready, like the rude, unseeing soldier who had stood at her threshold.

She clasped Elgar’s hand, and pulled her close to their mother and Musa. “Let’s move to the farthest corner of the square,” she whispered to her mother. “I can hear soldiers coming.” Her mother, now white with fear and weakened, readily deferred to Ayshe. They turned to the left and skirted the edge of the square to the south west corner, where the crowd was sparsest. At the entrance to the church bell tower there was a small alcove. Ayshe crowded in with her family. They’ve lured us here, she thought, so that they might slaughter us easily. How foolish we were to obey! She glared then at her mother’s obstinate face, her set jaw, her drooping, tired skin. She doesn’t know about the real world, thought Ayshe. She’s too old to understand that you mustn’t follow these people. If only I had been strong enough to say no! She felt ashamed for the stupidity of her family, and the stupidity of her people, so easily talked into their own death trap.

A voice interrupted her thoughts. “Sürgün, sürgün! It is sürgün!” She listened to this unfamiliar Turkish word. The voice went on: “They say we are traitors, and barbarians. They are coming—now—the whole Red Army, to teach us for ‘deserting,’ when we have done nothing!” Ayshe peered out of the alcove, and recognized Amet Kadyrov. He was a shorter, dark-haired young man with coal-colored eyes that glinted in the light of a kerosene lamp he held out before him. Ayshe put Elgar’s hand in her mother’s. “One moment, mama,” she said. And she ducked out of the alcove and walked over to Amet.

Amet’s eyes were almond-shaped like her own, and as Ayshe drew closer she thought they seemed to be fighting to remain cool, steady. They flicked nervously across the faces of the small group gathered before him. His lamb’s wool karakol was tilted to the side of his head at a bizarre angle and, in the orange half-light of the lamp he held out before him, he looked as though he hadn’t slept, as though some deep part of him was disturbed. Crazed, despite his tone of reason. Ayshe then noticed the heavy boots he wore. Also, winter boots. What did he and mama both know?

“Amet,” she said, “it’s me.” Amet turned to her.

“Ayshe.” He bowed his head in acknowledgment. “Ayshe, I am sorry to see you here too.” For a moment, his eyes rested warmly on hers. Ayshe had shared class with Amet in the Tartary school. Amet had been a good student. He and Ayshe competed for the top grades in history and rhetoric and outperformed each other in Russian. Outside of school Ayshe, like Amet, had been teased and taunted. The Russian and Ukrainian children had called her ‘rusalka chernaya,’ the black mermaid, for her dark complexion and dark hair, and the idea, Ayshe sometimes thought, that she was only half-human.

“What is sürgün, Amet? I’ve never heard this—sürgün. What does it mean?”

“Sürgün, sürgün,” said Amet woefully. “That is exile. Forever exiled. That is what they will do to us. They are counting us up now, like chickens, so they can set us in cages and send us to exile.”

“But where? On the mainland? In Ukraine?”

“No Ayshe, I do not know, but I think it will be far from here. I have heard the Soviets have sent many Volga Germans and Turkic people from the Union into remotest Siberia.”

“Siberia.” The descriptions of Siberia she had read in her school text books rushed to her mind. She pictured vast expanses of white, with only carts and buggies led by horses and donkeys through the snow. She knew too, that there were long, dry summers in Siberia, and that contrary to the way everyone talked about it, it could be a hot place. That heat too could be devastating for a family without shelter or a home.

“Yes, Siberia. Stalin has set up Gulags there.”

“Gulags?” This was another unfamiliar word.

“They are labor camps. We will be little more than slaves.”

In the square, the noise of the shouting was becoming louder. Amet and Ayshe turned towards it. The Tartary crowd was climbing up onto the rough platform of the officers. An officer was yelling through a loudspeaker: “Get back from here. Get back. If you do not move, you will be shot!” The marching sound was unmistakable now, and the crowd in the center of the square was panicking. A handful of soldiers had returned from rounding up the Tartars of the town, and they strode indifferently to the centre of the square, and began to butt the protestors with the ends of their rifles. Ayshe turned to Amet. “We must get away from here, this is very dangerous.”

“Yes. They are just waiting for the army now. I must get to my mother and father,” Amet stated. His parents were elderly, Ayshe recalled, and his father had avoided enlistment for that reason. “Yes, go to them,” she said.

“Do not try to run away from this Ayshe. Else, the soldiers will get you, or the Russian townsfolk, and that will be worse than sürgün. The best you can do is keep your family together, and stay living.” Amet bowed his head to Ayshe. “And do your best,” he said, “to speak Russian to them, and only Russian.”

As Ayshe crossed the few yards back to the alcove, a single shot rang out from the rynok center. Then, one more. She turned to see two officers on the podium firing their hand guns into the air. A warning. The small crowd around them was quickly dispersing. Ayshe was about to turn back to her family when she was forced down to the ground by a roaring noise. It swarmed over her and shook her entire body. Sharp painful jabs, echoing all around the square, punctuated the air. Ayshe felt as though these jabs were punctuating her own lungs, stopping her own breathing. The needling, shocking noise of rifle fire was blasting through the rynok. The marching soldiers poured into the square, having at last reached their target. Their rifles sounded for a moment or two longer, then stopped. In the chilling calm that followed, the marching of more and more soldiers was heard, as they surrounded the square. A wailing began, in the north of the square—the point, Ayshe thought, where the soldiers had first entered and fired in response to the officers’ warning shots. On her hands and knees, Ayshe crawled the remaining distance to the alcove and sat with her shaking, weeping family.

Ayshe’s tears soaked into her heavy winter clothes; the clothes meant to save her from the winter her mother had somehow seen coming.