Time and the Maya Apocalypse: Guatemala, 1982 and 2012

When you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, you must realize that she will soon be laid desolate. Those in Judea must escape to the mountains, those in the cities must leave it, and those in the country districts must take refuge in it. For this is the time of vengeance, when all that scripture says must be fulfilled. Alas for those with child, or with babies at the breast, when those days come!

Luke 21:20-23

This is the account, here it is:

Now it still ripples, now it still murmurs, ripples, it still sighs, still hums, and it is empty under the sky.

Here follow the first words, the first eloquence:

There is not yet one person, one animal, bird, fish, crab, tree, rock, hollow, canyon, meadow, forest. Only the sky alone is there; the face of the earth is not clear. Only the sea alone is pooled under all the sky; there is nothing whatever gathered together. It is at rest; not a single thing stirs. It is held back, kept at rest under the sky.

Whatever there is that might be is simply not there:

only the pooled water, only the calm sea, only it alone is pooled.

Whatever might be is simply not there: only murmurs, ripples, in the dark, in the night.

Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of the Mayan book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings, translated by Dennis Tedlock (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985), p. 72.

I. An Act of God

It was three in the morning on February 4, 1976. The rural Guatemalan town of Chimaltenango was asleep. Populated at that time mainly by Kakchiquel Maya, Chimaltenango was (and is) the gateway to Guatemala’s Maya highlands. The Pan-American Highway cut through the heart of the town, a vital artery that carried the outside world to Chimaltenango but also emphasized the local people’s isolation and marginalization from urban, Ladino Guatemala.

One minute later, at 3:01 am, the earthquake hit.

It registered 7.5 on the Richter scale and was followed by a second powerful 5.5 aftershock on February 6. By official count it killed 22,545, wounded 70,000, and displaced more than a million people—all numbers which probably underestimated those killed, injured, and left homeless in the nameless shantytowns that ringed the nation’s capital, Guatemala City, and in remote rural areas. Even Guatemala City, located 54 kilometers from the epicenter, was shattered; its water supply, telephone system, and electrical grid so damaged that even after repairs they would function erratically for at least a decade to come. Chimaltenango stood at the epicenter. The earthquake killed 9000 of the town’s people immediately, while many more succumbed to trauma and injuries in the weeks and months following the disaster. It destroyed every single building in town, save for a local health clinic, the town hall, and one private home.

In the wake of the tragedy, Chimaltenango’s survivors began to rebuild. For the many indigenous Mayas who had long infused their Catholicism with pre-Columbian traditions of cycles of destruction and rebirth, this was nothing less than cosmic business as usual. Yet for the growing number that turned from those beliefs to an increasingly relevant Pentecostal Protestantism, it was “an act of God.” In the post-earthquake Maya highlands, this was not figure of speech: a survey conducted by INCAP (Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama) just a few days after the quake in nearby Santa María Cauqué showed that 75% of local respondents attributed the earthquake, in one way or another, to “God’s will.”

Whoever was responsible, he or she was just getting started.

For some, it’s easy to smile at the turning over of the Maya long-count calendar on December 21, 2012. Certainly, it’s seized the imagination of New Agers and others who find it appealing to imagine an apocalyptic end to a post-industrial, polluted, and highly capitalized post-modern world—an end predicted by an ancient and noble indigenous culture, no less. The end of the Maya calendar cycle has attracted hype from both mainstream and alternative media for years, echoing the fin-de siècle prognostications that surrounded the Y2K panic at the turn of the last century. Although Maya experts such as noted epigrapher David Stuart dismiss such end-of-the world scenarios as “nonsense,” excitement about 2012 continues to build on websites and blogs (none run by Mayans themselves) that purport to have esoteric insider knowledge about the so-called “prophecies.” Never stopping to question the futility of capital accumulation at a time when humankind has only months left to live, any number of New Age entrepreneurs, travel agencies, and even the occasional anthropologist have been happy to cash in on the anticipated catastrophe. Potential prophetic purchases include books, paraphernalia—not least of all a protective Mystic Mayan Power Cloak available on an exclusive website and disaster-tourism packages to key Mayan ruins for those who wish to witness the End of Time from a ringside seat.

But what if the apocalypse already happened? And what if the world never even noticed?

Today, the small Central American nation of Guatemala is noteworthy for a series of extremes. First, it has the largest indigenous majority of any Latin American nation. The Mayan population, descendants of the great empire-builders of the so-called Classic Period (c. 250-900 CE), makes up more than 60% of the current population.

Second, Guatemala is home to what was once the region’s longest-running civil war. Over thirty six years, nearly 200,000 people died violently at the hands of their own government. This figure tops the combined number of people who died in the other, better-known countries of Central America (El Salvador and Nicaragua) during the civil wars of the 1980s.

And lastly, it is the most Protestant nation in Latin America. Although they are a very traditional people deeply vested in their own culture and their own understanding of history, many Maya “Indians” are Protestant, a trending factor among Guatemalans as a whole. More importantly, upwards of 80% of Mayan Protestants are Pentecostal.

None of these facts are unrelated, and what follows is a history of how Guatemalan’s eschatology—the interpretation of end times—following the catastrophic natural disaster of 1976 tied them together.

At its core, however, this story is far more specific and brutal. Although Guatemala’s civil war lasted for thirty-six years, the most concentrated period of murder occurred after the earthquake, between 1981 and 1983, when the Marxist-hunting government of Efraín Rios Montt, a general whose neopentecostal church had missionary ties to the United States, conducted a scorched-earth campaign against its own people, killing some 20,000. Although this period is commonly known as la violencia (the violence), the Maya remember the period by a series of other names as well. Of the 20,000 who died, 80 percent were Mayan, and many of their number were Catholics that had been called to political and social activism through their involvement in a movement called Catholic liberation theology. The government’s assault on their lives, politics, and culture during this period was so invasive, and so horrifically complete, that their survivors are inclined to call it the “Mayan holocaust”—or, as one elderly Mayan woman referred to it: the “desencarnación”, the loss of flesh, or loss of being. Some members of their community were so traumatized that they turned away from Maya Catholicism and became Pentecostals—like Ríos Montt.

Yet if they did so, it might not have been for the reasons Ríos Montt meant. Instead, Maya Pentecostalism could be regarded as a natural outgrowth of one of the Maya’s oldest cultural survivals: a belief in an apocalypse that would bring not a Christian-style end of the world, but a resetting of a long calendar cycle; a calendar cycle that included not only the recent violence but also the Maya’s entire history of conquest and subjugation; a calendar cycle that has been, quite frankly, awful.

II. Time and the Maya Apocalypse

The Western study of Maya understandings of time and space might be said to have begun in 1701, in the important prehispanic religious center of Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (then known as Santo Tomás Chuilá), when a Spanish Dominican friar named Franciso Ximénez decided to write down the mythico-history of the Ki’che people. With the help of native informants who recited the ancient texts, which until that time had been transmitted orally from one generation to the next, Ximénez transcribed the manuscript into the Roman alphabet and translated it into Spanish, making the first “official” modern copy of the text. Despite its lack of internal organization, and Ximénez’s haphazard approach to capitalization and punctuation, it became famous as the Popol Vuh, or the Book of the Council.

Others, however, call it another name, one that hints at how Mayan belief had absorbed colonial Catholic teaching, rather than the other way around: the “Mayan Bible”. Although Ximénez’s difficult manuscript now rests at the Newberry Library in Chicago, its stories of multiple creations, of Xib’alb’a—the underworld and its holy denizens—of important calendar cycles and of genealogies, stayed out in the world. Mayan beliefs have long rested comfortably within the Christianity of Catholicism, and for centuries Mayans passed down the Popol Vuh through oral tradition and other means of transmission—public dances and private rituals held in caves and other sacred spaces. Today, some Mayans use the Popol Vuh, and two other ancient texts in tandem with the canonical Christian bible to participate in a Catholicism defined by a worldview that Mayan people call “cosmovisión.”

Still, the very phrase “Mayan Christianity” is fraught. Although generalizations veer toward inaccuracies, the Mayans responded to the Spanish colonization first by fighting, then by retreating to remote and often mountainous rural regions, as far as possible from Spanish-imposed domination. Once there, they recovered as much of their original religion and lifeways as possible, re-inventing those that were lost. Broadly speaking, Maya spirituality today focuses on three key principles of balance and harmony: peace with the natural world that sustains life; peace with other people (including the dead); and peace with the deity—or, perhaps, deities. Although Mayan Christianity includes the belief in one God, it also involves prayer to many saints, gods, and spirits, such as Noj, one of the “owners” of mountains, or Maximón (San Simón), a trickster god with a saint’s name who assists in affairs both noble and nefarious, and is increasingly associated with protection for those making the long “illegal” trip to work in El Norte. These sacred beings are often considered to be present in spatial geography, particularly in mountains, which provide a sacred landscape visible in nearly every corner of Guatemala. Conventional wisdom has it that a person can see an active volcano from any given place in Guatemala. It’s little wonder that people would understand the natural topography to be living and holy, brimming with life force.

Atop this sacred, spatial geography of the “cosmovisión” lies Mayan religion’s complex system of numerology, divination, astronomy, and prophecies. This concern with time and counting is most famously expressed in the 260-day-calendar cycle used by almost all Mayans today, a vestige of the ancient Mayan Long Count. In Mayan thinking, time is an attribute of the sacred, a central sacrament of Mayan spirituality, and a subject of “overwhelming preoccupation.” “It would be more appropriate to call the Maya worldview a chronovision,” Miguel Leon-Portilla said more recently. “[T]o ignore the primordial importance of time would be to ignore the soul of this culture.”

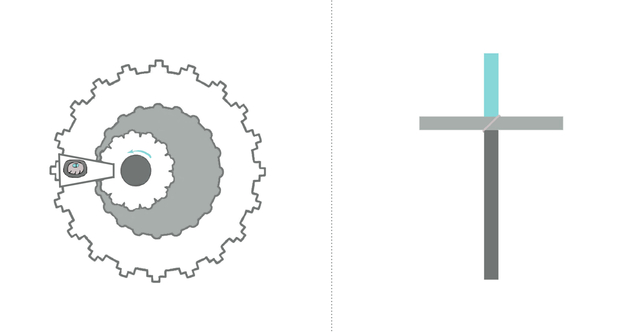

For the Maya, however, time moves differently than it does for Westerners. It is not linear. It turns in cycles, where history can be both anticipated and sometimes repeated. In eras both ancient and modern, Mayan time follows cycles of different lengths that run simultaneously and intersect at given points, something like interlocking cogs on differently-sized wheels. The tzolkin is a 260-day cycle, consisting of one cycle of twenty name days, and another of thirteen regular days. This combination of cycles within tzolkin is known as the Calendar Round. The tzolkin operates within a larger solar cycle known as the Haab, which consists of 365 days. The Haab, in turn, combines with a Venus cycle of 584 days; these, meshing like two wheels in a gear, produced the revolution that was known as the Short Count.

The Short Count operates within a much larger cycle known as the Choltun, or the famous Long Count, wherein time cycles are based upon nested cycles days that are multiplied by the sacred number of twenty. A Choltun is made up of thirteen cycles of 144,000 days (baktuns)—just over 394 and a quarter tropical years, or cycles of the sun. (Recent scholarship suggests that that the Maya believed the Choltun operated within yet another nested set of cycles known as the Great Long Count, consisting of 24 regular Long Counts. If such was the case, this renders concerns about 2012 especially irrelevant.) The Maya believed that the Long Count began at the beginning of the first manifestation of the cosmos, which dates, in our way of figuring it, to August 11, 3114, BCE. The Long Count lasts for 5,125 years, or thirteen cycles of 144,000 days (baktuns). We’re currently in the thirteenth and final baktun, which will draw to a close in December 21, 2012. This is the day 13.0.0.0.0 in the Maya Long Count, a date in “close conjunction with the Winter Solstice sun and the crossing point of the equator of the Milky Way and the path of the sun, what the ancient Maya recognized as the Sacred Tree” — Yaxche, the ceiba, the tree of Life, an axis mundi that unites heaven and the underworld with the terrestrial world. It also brushes up against Christmas and the western New Year, thus inter-nesting significant holy days from one tradition into another.

Contrary to dire media predictions, the pre-Columbian Mayans did not actually believe that the world would end in apocalypse at the end of the Long Count cycle. According to the Choltun, after Dec. 21, 2012, a new cycle will begin.

The end of a calendar cycle is no a small matter, however. It is a time of great change. The Popul Vuh explains that creation has come to a complete end on three prior occasions, resulting in our current era, the fourth creation, which we inhabit as Hombres de Maíz, or People of the Corn. The decades leading up to the end of the calendar cycle, especially of a Choltun, are a dangerous and liminal time. In prior creations, there was a lapse of time between the destruction of one creation and the beginning of another. For example, the baktun we’re in, the thirteenth, began in 1,618, preceded by the toppling of so many Old and New World societies in the decades before. Therefore, the end of this Choltun should fall only after one creation had already come to its end.

By our calendar, that would have been sometime between 1980 and December 2012.

III. Roofing for the Soul

In the days and weeks that followed the destruction of Chimaltenango and the rest of the Guatemalan countryside, it was clear that the earthquake had shaken more than buildings and houses; it had also rattled Guatemala’s soul. A survey conducted shortly after the event found that no fewer than seventy-nine out of 101 families surveyed—nearly 80 percent—believed the quake to be either a sign of God’s displeasure or a divine call for redemption.

What God was displeased with, and what needed to be redeemed, however, was up for debate. As both a natural catastrophe and metaphor, the earthquake shattered the already fragile social and governmental infrastructure of the country. Politically, the country had been ground zero for the U.S.-led Cold War in Latin America since 1954. That year, the newly-empowered CIA helped orchestrate the overthrow the government of Jacobo Arbenz, the more progressive of two presidents who were freely elected during Guatemala’s so-called “Ten Years of Spring” (1944-1954)—a brief respite in the nation’s long and sad history of repressive, authoritarian governments. Following the Arbenz coup, the nation fell into a downward spiral of violent reprisals between a repressive military government and those who sought to overthrow it for something like Castro’s Cuba. By 1976, the country was sixteen years into an unevenly matched and bloody civil war between Marxist guerrillas (the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity or URNG) and a military-controlled government, whose U.S.-trained/led/guided death squads had carried out Latin America’s first systematic wave of “disappearances” of labor and peasant leaders.

Guatemala was and is a traditionally Catholic country, but in the disaster’s aftermath the Church was roiled by divisions that not only kept it from acting decisively, but also may have helped pull the country further apart. On the one side—representing the interests of the rich, the powerful, and the entrenched— was the deeply conservative Archbishop, Mario Casariego, the nation’s “pastor.” Only a few hours after the first round of shaking was over, the night of February 4, Casariego chided the traumatized country for the demonstrations, strikes, and radical political mobilization that he said had earned God’s punishment.

Yet for Catholic lower clergy and laypeople who were engaged with Liberation Theology—the Latin American Catholic Church’s turn, beginning in the 1960s, from millennium-long alliance with the powerful toward a “preferential option for the poor”—the earthquake was a trumpet call to social action. It was God’s sign that it was time for Guatemalans to build a tierra nueva, literally a “new land,” based on a radical, but also very Biblical foundation of economic and social justice. In the days immediately following the quake, priests, nuns and lay workers organized a series of land invasions of marginal urban areas around Guatemala City’s vast barrancas (ravines) and property seizures in the name of homeless and displaced people. As one priest explained,

the intense joining together of people-church in relation to the housing problem resulted from our theological contextualization of the earthquake. We said that the earthquake was God’s signal that we should leave the ravines to search for a communal identity.

The 1976 earthquake added such unprecedented momentum to the growing popular resistance movement that social scientist Phillip Berryman later described it as a “detonator” of revolution.

In the middle were the Mayan traditionalists, who strongly identified themselves as Catholics but whose lived religion freely mixed Mayan beliefs and Christianity. What they needed, at least at first, was not politics but material aid and a more literal, less metaphorical explanation of why their lives had been up-ended. For many, the explanation that made the most sense came not from the Catholicism they had worshipped their entire lives, but a “new” Christianity—one that would expand rapidly in the months and years that followed: that of the Protestants whose influx of aid agencies after the earthquake had offered spiritual succor along with relief supplies, a practice popularly dubbed “lamina por anima,” or roofing for the soul.

Although Protestant missionaries from mainline denominations like the Presbyterians and Methodists had worked in the country for a century, the explosion of conversions that followed the earthquake and the nadir of the civil war can be traced to the late 1960s, when US-based mainline missions, fearing expropriation but still wanting to offer a “spiritual alternative to communism,” turned their work over to native leadership. Guatemalan Protestantism began to assume a local character—and that local character usually meant an affinity for Pentecostalism, a experiential variety of Christianity that involves a bodily experience of God (“baptism in the Holy Spirit,”) and emphasizes “signs and wonders” like miraculous healing, speaking in tongues, and prophecy.

While radical Catholics had read the earthquake as a call to social action, these evangélicos (the Spanish word for all Protestants), cast the earthquake and ensuing violence as a literal sign from God that the end was near. The Pentecostals were best positioned to catch the spiritual fallout. One denomination in particular, El Calvario, a Guatemala City-based Pentecostal church, benefited from a member’s earlier prophetic dreams of tectonic cataclysm. Taking her divinations seriously, El Calvario’s congregation had warehoused large amounts of food and emergency aid, a stroke of foresight that convinced many in the earthquake’s aftermath of the church’s spiritual legitimacy, and, indeed of Pentecostal churches in general.

Pentecostal denominations grew by leaps and bounds. Although the statistics are imperfect, in 1960 approximately five percent of Guatemala had been Protestant. By 1980, they made up nearly a quarter of the overall population. And two years later, one of those post-earthquake converts—a non-Indian elite and General named Efraín Ríos Montt whose neopentecostal church, Iglesia Cristiana El Verbo, had originated as part of the “Jesus Freak” movement in 1960s California—became Guatemala’s president. Or more accurately, its dictator.

IV. When the Saints

By 1983, Chimaltenango was again reeling from catastrophe, but this time at the hands of human, rather than tectonic forces: those of the Guatemalan army.

Ríos Montt and his military junta took control of Guatemala’s government in March of 1982, ostensibly to bring law and order to a country that had seemed to teeter on the brink of a Marxist take-over. In the late 1970s, Guatemala’s guerrillas had built a substantial presence in certain parts of the country. The government believed they had significant links to Cuba, Nicaragua’s newly-victorious Sandinistas, and El Salvador’s FMLN, which also appeared at that time to be on the cusp of success. More devastatingly, the governments preceding Ríos Montt believed that the popular resistance enjoyed wide support among the indigenous population, and labeled the Catholic activists that ministered to that indigenous population “communists” and “subversives.” Believing they were dealing with a cadre of leftist guerillas who, following Mao’s dictum, swam among the Maya population like fish, prior governments had made the horrific decision to drain the sea.

Ríos Montt did not disagree. From 1982 to 1983, his army carried out a scorched-earth campaign in the Guatemalan highlands to route the guerrillas and anyone they thought might possibly be aiding and abetting them. A “scorched earth” campaign is exactly what it sounds like. In Chimaltenango, as in other areas of the so-called “zones of conflict” (areas that the Army identified on a map by color coded push-pins in red, yellow, and green as rebel territory), this meant that soldiers entered Maya villages and formed “civil patrols” of local men to identify guerrillas or their sympathizers. Local informants, shrouded in a hood to hide them from incrimination (even though a lifetime of proximity made individual voices easily identifiable), singled out “subversives” from among their friends and family. These were immediately taken into military custody, never to be seen again. Men, women, and children were burned alive in their homes. Soldiers hastily executed and buried many in mass graves, while homes and cornfields were razed to the ground.

By 1983, the army had routed the armed resistance and, by its own count, eliminated 440 indigenous villages entirely. Twenty thousand had died and an international emergency relief agency noted, “a large segment of the Indian population is facing starvation and social disintegration.”

The actions of Ríos Montt’s army also blew a hole through in the country’s religious landscape. The scorched earth campaign tore through the ranks of the Catholic lower clergy and laypeople who had doubled down on Liberation Theology, and the Maya Catholics who had been caught in the middle. For those who felt as if the world was ending, Pentecostalism offered immanent succor. One urban Pentecostal group briefly published a newspaper in order to cover the apocalypse. Its final edition, the third of a Trinitarian three, probably published in late 1982, carried the very present tense headline, “El Señor Viene [The Lord Comes]: His return is imminent, this is an alert.” The issue featured articles with titles like “Earthquake: plagues, general commotion, and many afflictions, the sun and moon will be darkened, and the mountains will fall”, “The Final Cataclysm;” “Know the signs: the sound of the trumpet, declares Paul of Tarsus,” and, reassuringly, “The Teacher: Do not be Afraid: Trust in Me.”

Ríos Montt also hinted at the good news, and from no less a pulpit than the presidential palace. During his 1982-83 presidency and throughout the scorched earth campaign, he trumpeted his religious beliefs, never so clearly as on his Sunday night television broadcasts to the nation. These were officially known as “discursos del domingo”—Sunday discussions, but were often known as Ríos Montt’s “sermons.” A charismatic leader in every sense of the word, Ríos Montt believed that he was leading his people into a prophetic moment in the nation’s history, what he called “an historic moment, a moment of national awareness” and “a marvelous time.” God and the nation had a covenantal relationship, he declared in April of 1982: “We rely on God, we rely on God … because He has given authority: you and I and the Junta of Guatemala, the entire family (la familia completa) … Guatemala has a different image … we have a agreement (compromiso), between Guatemala and God. (emphasis mine).

Ríos Montt was not alone in this sense of destiny. Certain sectors of Guatemala’s rapidly growing Protestant population believed that the evangelical chief-of-state’s administration represented a crucial dispensational moment in Christ’s unfolding plan. This was “God’s hour for Guatemala” (la hora de Dios para Guatemala), proven by the bonanza growth in the church’s share of the religious market. The worldwide “church growth” movement, known as “iglecrecimiento”—a clever neologism combining “iglesia,” church, with ‘crecimiento,” growth—sought to rapidly evangelize nations where Protestantism had recently taken root, like the Philippines and Korea. As a rejoinder to Liberation Theology, Guatemala offered a near perfect case study for what iglecrecimientistas called “dominion theology”: by the early 1980s the country’s population was 30 percent Protestant—making it the “most Protestant” country in all of Spanish-speaking Latin America.

A vocal minority of Guatemalan evangelicals, including the leadership of the general’s church, Verbo, argued that Ríos Montt’s presidency, along with the uptick in Pentecostal conversion, signaled the fulfillment of the biblical prophecy leading to the Second Coming of Christ. That Guatemala was embroiled in a fratricidal war only offered further evidence of Guatemala’s prophetic moment. As one iglecrecimientista wrote, “The crisis of ethical and social order that we confront in this country is that of a nation crying out in search of God.”

While Ríos Montt never claimed actual messianic status for himself, by mid-1982, his “sermons” showed how his understanding of that prophetic moment in history had begun to change. God’s relationship was no longer with Guatemala, but with every Guatemalan; it was not just a loving relationship, but a punitive one too. During the height of his rural scorched earth campaign, Ríos Montt admonished his people: “God loves us, God loves Guatemala, God loves you,” he explained, “and those who He loves he disciplines, He loves and He smites (golpea), so that you wake up and react and start to look for what truly matters, that you reconsider your importance, your humility, you reconcile yourself with Him, your creator, with your King, with your Lord.”

By building a theological framework around Guatemala’s suffering, even at the hands of the security forces that he himself commanded, Ríos Montt constructed a salvation narrative that appealed to the desperation of everyday Guatemalans, even as it justified his own government’s violence: God tests his most beloved.

The hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the first permanent Protestant missionary to Guatemala, celebrated with great fanfare in October of 1982, suggested to many Protestants that God’s tests were not in vain. After months of planning, Protestants flooded the capital from all accessible parts of the country; approximately 300,000 convened in the Campo Martí (a military parade ground in central Guatemala City) to pray, sing, and to hear evangelical leaders (including the man known as “the Latin American Billy Graham,” televangelist Luis Palau) and Ríos Montt himself pray and offer thanks for Guatemala’s redemption. One participant in the centennial celebration recalled, “As we sang, ‘When the Saints go Marching In,’ we could almost visualize our heavenly home, we felt we were almost flying through the air toward a glorious encounter with Christ Jesus.”

V. The Pan-American Highway Revisited; or Protestantism and the Maya Apocalypse in Rural Guatemala

Beyond the Campo Martí, beyond Guatemala City, in rural places like earthquake-rocked Chimaltenango, threaded by the Pan-American Highway, rates of conversion to Protestantism were actually much higher than in urban areas. In conflict zones, the repression of Catholics and other overwhelming circumstances drove people to seek out new religious options with new explanations for their hardships. This was not a retreat to a foreign God. Among Mayan Protestants, many belonged to locally-based Pentecostal denominations that had few, if any, direct ties to the foreign missionary organizations that had had a long but relatively unproductive history in the country.

Of course, General Ríos Montt’s strong association with Pentecostalism and the counterinsurgency strategy unquestionably influenced some Maya to convert to Protestantism in the interest of self-preservation. There was undoubtedly an element of spiritual “me-too-ism” as people used evangélico identity as a shield to protect themselves from the violence raging in the countryside.

Yet to attribute the conversion boom, which plateaued in the early 1990s, to simple expedience seriously underestimates the impact that Protestant conversion had on society and individual lives. The all-out military assault on the highlands had destroyed families, villages, and, where it had still been strong, the costumbre (lifeways) that had lent indigenous communities their distinctive identities for hundreds of years. In those spaces of utter hopelessness, hope grew back. Small Maya Pentecostal congregations formed in society’s remnants, an effort at recovery that one pastor referred to as “trench faith.” In abandoned storefronts, private houses, or even palm-front shacks, local leaders built makeshift churches. Shaped around local knowledge but with a Protestant theology and sensibility, people found ways to reconstruct shattered lives and to wrest meaning from the anomie of violence.

The meaning that they fought for, however, might not have been as new as it seemed. Culturally, Pentecostalism’s interpretation of the meaning of violence and the immanence of the Second Coming—specifically in the late twentieth, early twenty-first century—may have felt familiar. While Protestantism adamantly rejects the kind of “syncretism” and “idolatry” that they strongly associate with Catholicism, the Mayan “cosmovisión” of apocalypse that nestled within Spanish Catholicism also fits within modern Mayan Pentecostalism. Mayan Pentecostalism remains as informed as Maya Catholicism by a larger cosmovisión of the earth, humanity, and the cosmos shared by indigenous pastors and church members alike.

Prophecy and the apocalypse are areas where Pentecostalism and traditional Guatemalan Mayan beliefs most noticeably overlap. Believers in both systems receive messages from the supernatural in dreams, sacred texts, or in an altered spiritual state. St. John’s apocalyptic visions in the Book of Revelation also remain as appealing to Pentecostals in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries as they likely did to Catholics in the sixteenth and seventeenth. Nearly all Mayans, regardless of what they believe, consider themselves Christians, so it shouldn’t be at all surprising that St. John’s visions fuse so readily with the Long Count calendrical prophecy, conflating the Second Coming of Christ with the late twentieth, early twenty-first century end of the Choltun. Many of the first Protestant missionaries were just as premillenialist as the earliest Catholics: their message of Christ’s imminent Second Coming inadvertently recalled the old Mayan worldview of chronovision. Even within the autochthonous Mayan Pentecostal theology that developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the old premillenist-chronovision themes predominate.

A second resonant aspect of Mayan apocalyptic thinking came not from ancient native spirituality but from Catholicism: the sacralization of suffering as anticipated in the “time of tribulation” described in the Book of Revelation. To be sure, traditional Mayan religion, like many religions, includes a strong element of fear and disease. Even today, for example, many people fear the capricious nature of the Tzuultaqa’, the “owners” of mountains, who, along with various saints and thinly-disguised deities, can wreck havoc with personal and community lives and fortunes. Contemporary Mayan history itself is defined by loss and oppression. But it is the Catholic contribution to contemporary Mayan belief that makes suffering something greater than simple misfortune. As one scholar explains, Catholicism makes “suffering no longer a punishment, a providential way of correcting offenses, but, rather, a way of purification.” Mayan Protestants expressly reject the gods, daykeepers, and mountain spirits of the traditional world, but many also nonetheless retain the ancient Christian idea, now fully Mayanized, that suffering is a way of advancing the Kingdom of God. This they found in abundance during the period of la violencia.

At the other end of these struggles was a great reward. As subscribers to the doctrine of premillennialism, Mayan converts to Protestantism (especially Pentecostalism) in the early 1980s believed that the Second Coming of Christ was imminent—but only after the Great Tribulation, a period of signs, wonders, suffering and trials for God’s people. The parallels between the biblical descriptions of this prophetic ordeal and the reality that so many Guatemalans were living were almost too numerous to mention. Earthquake, fire, death, and internal exile—it felt like nothing less than the breaking of the Seven Seals of the Apocalypse: “There was a violent earthquake and the sun went black … the whole population … took to the mountains to hid in caves among the rocks … For the Great Day of His anger has come and who can survive it?” (Revelation 6:12-17).

This, indeed, was Guatemala’s kairos, its prophetic moment: to bear witness to the Great Tribulation but to rise, faithful and triumphant, with the Lord on the day of His final Coming—an interpretation which vested logic and meaning into what was otherwise inexplicable suffering. It was a theodic answer—theodicy being the question of how a loving God permits evil—to the riddle of otherwise incomprehensible violence. “These are the people who have been through the great persecution, and because they have washed their robes white again in the Blood of the Lamb, they now stand in front of God’s throne and serve him day and night in his sanctuary; and the One who sits on the throne will spread his tent over them … and God will wipe away every tear from their eyes.” (Revelation 7:16-17, after Is. 25:8).

For the Mayan Pentecostals who experienced la violencia, who had moved from folk Mayan Catholicism to Pentecostalism, this was centuries of religious belief made flesh. It was the hope of reaching the end of an era—perhaps a baktun—of suffering that began after the first Spanish conquest. It was the final turn of a cycle, a closing narrative of divine judgment and salvation that was Maya and Christian simultaneously, that sacralized the nation’s struggle, providing a metaphysical logic sufficient to explain even the deepest suffering of the Guatemalan people.

VI. History and the Maya Holy Spirit

General Efraín Ríos Montt’s epitaph as a horseman of the apocalypse, or a prophet of the Second Coming, would be debated in his own lifetime. He “found it easier to apply the Old Testament law, summarized in ‘an eye for an eye, tooth for tooth,” fellow Protestants criticized. “[H]e has not wanted to, nor has be been able to apply the spirit of the New Testament to his government.” On August 8, 1983, Ríos Montt was ousted in a coup d’etat, after a group of fellow Army officers and powerful businessmen—all smarting from Ríos Montt’s prohibitions against graft and moral chidings to give up their mistresses and girlfriends—judged him a religious kook and no longer fit to hold office. The violence he had presided over continued, however—a genocide of the Maya people later publicized in the human rights campaigns of people like Rigoberta Menchú and, more importantly, in truth commission reports and in the courts. Ríos Montt dodged prosecution for decades, but on January 26, 2012, Guatemala formally indicted Ríos Montt for genocide and crimes against humanity.

Still, Ríos Montt remains influential as a political leader even today. It seems that his place in Guatemala’s history is (at least for the time being) as much framed by his own hagiography and by local understandings of theology as by secular measurements such as human rights and democracy. Membership in Guatemala’s evangelical churches hasn’t reached the levels pastors once hoped, but it continues to trend upward, though far more slowly than in years past. And although the theological trends in Guatemalan Protestantism in general have begun to shift to other themes (prosperity gospel and spiritual warfare among them), the interest in apocalyptic interpretation among many Mayan Protestants remains strong. The 2012 election to the presidency of one of Ríos Montt’s loyal generals, Otto Pérez Molina, was but one back-to-the-future convergence with the difficult past. Among a people steeped in history’s cycles, it perhaps fueled hope that the present era of very literal, very personal suffering and violence is soon coming to an end.

In a sense, this conflation of destiny and time is more Mayan than Western: as Fernando Escalante Gonzalbo has noted, “in the traditional Christian idea, world history does not, strictly speaking, have meaning.” Quoting Voegelin, Gonzalbo continues, “Only transcendental history, including the early pilgrimage of the Church, has direction toward its eschatological fulfillment. Profane history, on the other hand, has not such direction; it is waiting for the end; its present mode of being is that of saeculum senesecens, of an age that grows old.”

In Mayan life, however, it is the ageless, not aging, chronographic cycles that unite the sacred with the profane—that see in everyday events, and recent history, the promise of change. As devout Christians, Mayan Pentecostals do not dread the end of the age, but anticipate it. Although disappointment ran high when the year 2000 came and went without event, the churches see hope on the horizon: today, December 21, 2012, ends the baktun that saw the Maya under Spanish domination, that saw the horrific violence of twentieth century Guatemala. The new baktun begins now.

“If ye have ears, then listen.”