Indelible Ink: The Deep History of Tattoo Removal

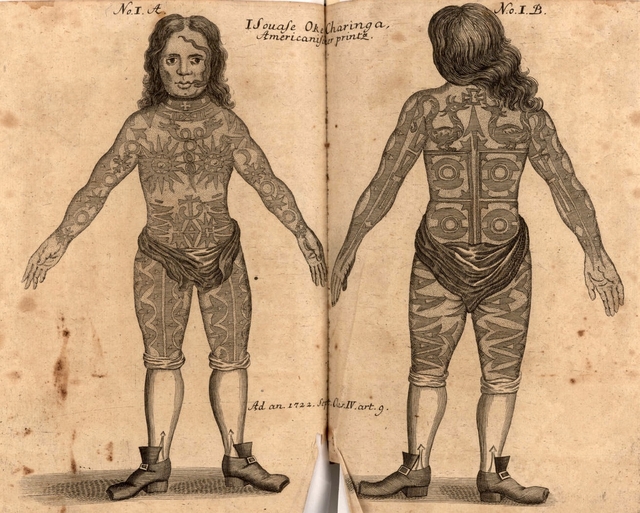

Europeans and indigenous Americans being judged at the court of Nature for modifying their bodies, from the frontispiece to John Bulwer’s Anthropometamorphosis (London, 1656). Wikimedia Commons

In 1681, after several months of raids on Spanish settlements, a group of English pirates traipsed across Panama on their way to the Atlantic. An accident involving gunpowder had left the buccaneers’ surgeon, Lionel Wafer, too injured to walk with the others, and he was subsequently left behind somewhere in Darién. Staying with the region’s Kuna people while waiting for his leg to heal, Wafer noted his hosts’ “delight” in decorating their bodies both with temporary paint and with “finer figures … imprinted deeper” into the skin. These latter figures, he wrote, were first sketched on the skin, “then they prick all over with a sharp Thorn till the Blood gushes out; then they rub the place with their Hands, first dipp’d in the Colour they design; and the Picture so made is indelible.” Wafer himself was painted by the Kuna, but either declined to be tattooed or was not offered the opportunity.

One of his companions, however, received “one of these imprinted Pictures” and then “desired” Wafer, perhaps with a hint of desperation, to get it “out of his Cheek.” Wafer’s best efforts as a doctor and surgeon made little difference, however: “I could not effectually” remove it, he reported, even “after much scarifying and fetching off a great part of the Skin.”

The growing ubiquity of the tattoo in contemporary culture (21% of the U.S. population now has at least one tattoo, according to a 2012 survey) has diluted some of the shock and fascination such markings used to generate. But an even greater factor behind the diminished reaction to modern tattoos may be the ready availability of effective removal procedures. With a whole industry standing by to correct tattoo regret, getting inked now might seem to many only a semi-permanent body modification.

While these contemporary laser removal techniques are only around forty years old, efforts to erase or rewrite tattoos are much, much older. One of the earliest written descriptions of a procedure can be found in the Tetrabiblon, a sixth-century encyclopedia of medicine written by a doctor named Aetius, who practiced in Alexandria and Constantinople. He wrote:

They call stigmata things inscribed on the face or some other part of the body, for example on the hands of soldiers … In cases where we wish to remove such stigmata, we must use the following preparations … When applying, first clean the stigmata with niter, smear them with resin of terebinth, and bandage for five days … The stigmata are removed in twenty days, without great ulceration and without a scar.

In the Mediterranean world of Aetius’s era, those most likely to be tattooed were soldiers—marked by the state with the number of their unit, as a preventative measure against desertions—and slaves who were tattooed either for the crimes that had resulted in their enslavement or as punishment for misbehavior (common tattooed phrases included ‘Stop me, I’m a runaway’). While there were also sacred tattoos throughout the Mediterranean, intended to mark their bearers as devotees of particular gods, many tattoos marked control by a human master: something that might have made former soldiers and slaves eager clients of Aetius.

By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, documentation of tattoo removal was often found in accounts of Europeans in contact with cultures overseas—particularly, although not exclusively, societies in the New World. The failed effort to remove the English pirate’s facial tattoo was not the only attempt at such a procedure in the early modern Atlantic world. A number of French, Spanish, English, and Native American sources suggest that people of the period could regret their permanent body modifications just as much as modern people do.

Tattoo removal in the past, however, reflected something more powerful than transient personal taste. Attempts to undo seemingly permanent body modification remind us how much the cultural aspects of physical appearance mattered, particularly in determining personal and collective identities. Inks and dyes, fixed under the skin, told stories about one’s past: who one knew, where one had been, even who one had been. One might wish, or others might insist, that such stories be ignored, forgotten, erased. This is the underexplored side to the history of body modification: regret, resentment, and painful policing of aesthetic and social boundaries.

Put another way, a tattoo could stamp such strong social or cultural affinities that it needed to be scrubbed from the body’s record.

“Souase Oke Charinga, Americanischer printz,” in David Richter, Sammlung von natur- und Medicin- wie auch hierzu gehörigen Kunst- und Literatur-Geschichte (Leipzig, 1722). The John Carter Brown Library at Brown University

1698, Brest, France: Interrogation notes outline a conversation between an Intendant Desclouzeaux and two brothers, Pierre and Jean-Baptiste Talon. The tattoos upon the Talons’ bodies were one of the topics of discussion.

A remarkable set of journeys had brought the Talons back to France, which they had left fourteen years earlier as members of the final, disastrous La Salle expedition. They were young children when their parents had joined the venture, which was intended to locate the mouth of the Mississippi and then establish a colony some distance inland. Failing to spot the river, the expedition dissolved in the wake of La Salle’s assassination by some of his own disgruntled colonists and an attack by Karankawas on the expedition’s settlement at Fort St. Louis. Pierre and Jean-Baptiste, along with their three siblings, were some of the group’s only survivors.

Pierre was taken in by the Hasinai, another local Native American community, while Jean-Baptiste and the other children were adopted by Karankawas. A few years later, Spanish parties searching for evidence of their French rivals found the Talon children, and they were taken to Mexico City, where they became servants in the viceroy’s household. The oldest brothers then entered into Spanish military service until the ship they served on was captured by the French. Surprised to find survivors from La Salle’s voyage on a Spanish ship, French officers escorted the brothers to France, questioning them closely about the lands along the Gulf Coast, the Indian societies they had lived among, and what Spanish intentions toward the area were.

The report said little about how the siblings looked after years living in coastal Indian communities and then in New Spain, except for this:

the said Talons … fell into the power of the savages, who first tattooed them on the face, the hands, the arms, and in several other places on their bodies as they do on themselves, with several bizarre black marks … These marks still show, despite a hundred remedies that the Spaniards applied to try to erase them.

There are no portraits of the Talons, nor any more detailed accounts of their “bizarre black marks,” but we can get an idea of their appearance from a 1687 description of another Gulf Coast castaway. Enríquez Barroto, one of the Spanish captains searching the coast for the French ‘interlopers,’ had instead found a Spanish child named Nicolás de Vargas living with Atákapas along what is now the Calcasieu River in southwestern Louisiana. Barroto reported that the boy had “a black line that goes down the front to the end of his nose, another from the lower lip to the end of the chin, another small one next to each eye and, on each cheek, a small black spot. Like the nose, the lips also are blackened, and the arms are painted with other markings.” The Talons would likely have had similar tattoos.

Desclouzeaux’s notes say nothing more about the “hundred remedies” that the Talons had been subjected to. One suspects that some of them were painful, or at the very least unpleasant—perhaps as much as the original process of being tattooed. Why had the Talons’ Spanish hosts (or captors, depending on one’s perspective) tried so hard to scrub away the traces of the children’s pasts?

As the viceroy’s family scoured the Talons’ skins in Mexico City, their efforts might have been influenced by stories of Gonzalo Guerrero, a Spaniard who famously landed in Yucatán in 1511 as the result of a shipwreck. Stories about the castaway were more legend than fact, but all agreed that Guerrero had joined the Maya and refused to rejoin Spanish society despite efforts by the Cortés expedition and others to recover him. A key reason he supposedly gave to Spanish messengers for his permanent transculturation? His tattoos. Chronicler Bernal Díaz claimed Guerrero told an envoy: “I am married and have three children, and they have me as a lord and captain … go yourself with God, for my face is tattooed and my ears are pierced. What will those Spaniards say of me if they see me like this?”

Rolena Adorno has argued that the Guerrero tales reflected Spanish fears of hidden heretics or conversos undermining religious purity. In turn, Guerrero’s decision to stay with the Mayas may have reflected his fear of those fears. The stories also registered concern that appearance, behavior, and identity were all easily mutable: Guerrero’s tattoos might transform him, irrevocably, into a Mayan warrior.

Once the Talons were back in French hands, there is no evidence that their countrymen prioritized erasing their tattoos, as the Spanish had. Far from it. Instead, they hoped to utilize their altered appearances, and their knowledge of indigenous languages, to aid new French expeditions to the Gulf region as translators and guides. The French officers placed the two Talons with a Canadian company that accompanied Pierre Le Moyne, sieur d’Iberville, on his second voyage to the Gulf. The five Talon siblings, accompanied by their stubbornly indelible tattoos, continued to circulate through the Atlantic, some remaining in France, others settling in Louisiana and Canada.

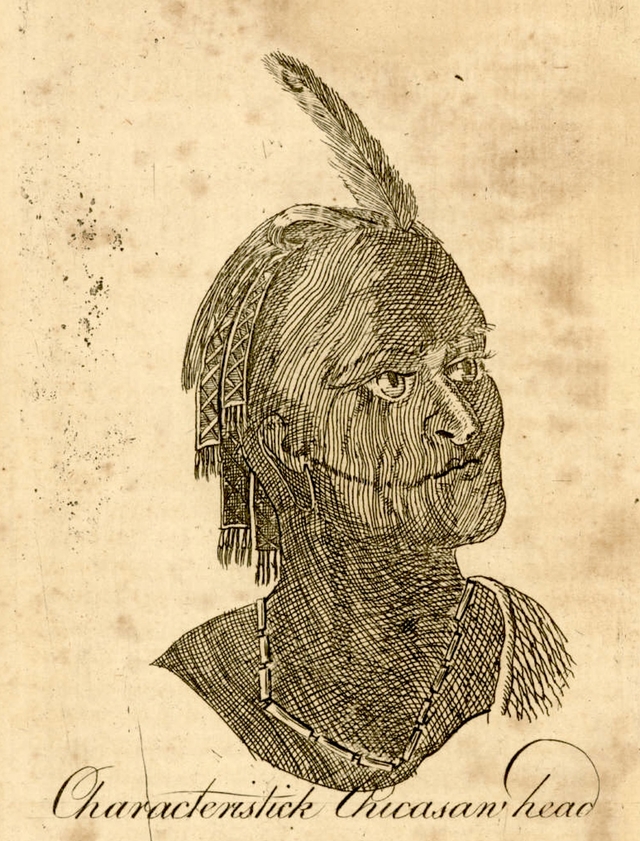

Bernard Romans, A concise natural history of East and West-Florida (Philadelphia, 1776), 58. John Carter Brown Library at Brown University

The Talons did not report how they felt about their tattoos. They may have valued them, or they may have sought their erasure. Some of those tattooed, however, wanted to keep their markings, only to find themselves subject to the violent interventions of others.

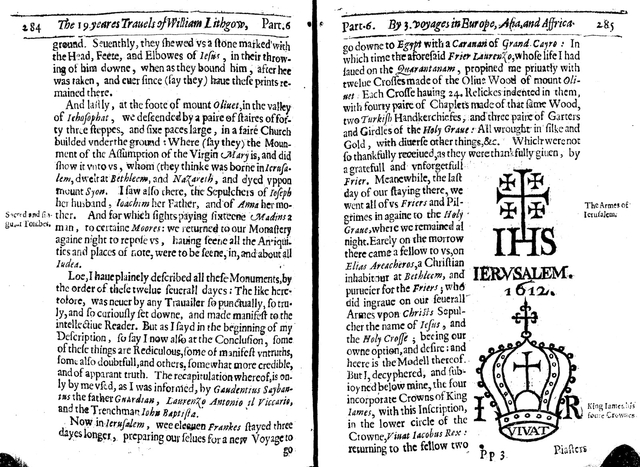

A Scottish traveler to Jerusalem in the early seventeenth century, William Lithgow, participated in what was a common practice for pilgrims to the Holy Land: receiving a commemorative tattoo, the so-called ‘Jerusalem mark,’ while visiting the site of Jesus’s tomb. Lithgow paid two piasters, he later wrote, to have “the name of Jesus and the Holy Crosse … engraved” on his right arm. A courtier to King James VI and I, Lithgow asked the tattooist to add to this image “The Neuer-conquered Crowne of Scotland, and the now Inconquerable Crowne of England, ioyned also to it; with this inscription, painefully carued in letters, within the circle of the Crowne, Viuat Iacobus Rex.”

Returning from his pilgrimage, Lithgow was detained in Spain upon suspicion of being a spy. There, he claimed, he was imprisoned and tortured—and when his captors discovered “the marke of Jerusalem … joyned with the name and Crowne of King James” on his arm, they “gave direction to teare asunder, the name and Crowne” of what they called “that Heretike King, arch-enemy to the Holy Catholike Church.” Lithgow’s torturers wrapped cords around his arm, then tightened them until they cut “the Crowne, sinewes, and flesh.” Permanently maiming him, this act was intended to punish, and to erase Lithgow’s bodily connection to his Protestant king and country. An unintended effect, of course, was to give Lithgow a claim to martyrdom on behalf of his “matchlesse Monarch”.

Lithgow’s tattoo was attacked by his captors as a symbol of beliefs they found offensive, a sign of faith and loyalty they rejected. A tattoo celebrating a British, Protestant king would have been, under any circumstance, unappealing to Spanish Catholics. But in other settings, it was not the tattoo’s symbolism or imagery that made it a target for removal, but rather the unauthorized body that it appeared on.

Lithgow’s tattoo from Jerusalem, as depicted in William Lithgow, The Totall Discourse of the Rare Adventures and Panful Perigrinations (London, 1632), p. 151. Wikimedia Commons

Examples from Native American communities demonstrate collective enforcement of standards regarding who merited tattoos. Trader James Adair, living among Chickasaws in the 1740s, wrote, “the blue marks over their breasts and arms [are] … as legible as our alphabetical characters are to us.” Adair asserted that these “wild hieroglyphics” were used in order to “register” their bearers “among the brave.” The implications for one’s status, if tattooed, were profound. Signs of achievement, tattoos could also single out captives taken in war for particular torture. Adair suggested that fighters taken captive who were “pretty far advanced in life, as well as in war-gradations, always atone for the blood they spilt, by the tortures of the fire,” arguing that it was by their tattoos that an individual’s war history was known. Such risks, however, were outweighed by the prestige the “hieroglyphics” carried within one’s own community, leading some, Adair wrote, to give themselves tattoos without having first performed the deeds necessary to earn them. “The Chikkasah … erazed any false marks their warriors proudly and privately gave themselves—in order to engage them to give real proofs of their martial virtue,” Adair commented. In a public shaming, the perpetrators were “degraded … by stretching the marked parts, and rubbing them with the juice of green corn, which in a great degree took out the impression.”

One might call these tattoos forged or counterfeit, except that neither term is quite accurate: the tattoos themselves were real, as the culprits had been painfully and publicly reminded. But the social motivations behind them were judged as unjustified by others, who then required that the claims made by the marks under the skin be nullified. Anthropologist Alfred Gell has argued that “a tattoo … is always a registration of an external social milieu,” adding, “the apparently self-willed tattoo always turns out to have been elicited by others, and to be a means of eliciting responses from others.” While the universality of this claim is debatable, it does suggest a corollary: that tattoo removal is also a registration of a social milieu, either prompted—or forced—by relations between people.

Whether voluntary, as in the case of Wafer’s buccaneer companion, or involuntary, as for Lithgow, the removal of early modern tattoos demonstrates how high the cultural stakes were for those with body modifications. The social alienation of having an unusual or collectively disapproved-of appearance, it seems, could be more agonizing than the “scarifying and fetching off a great part of the Skin.”