The Curse of Coherence: Cold War CIA Funding for Oulipo’s Confidence-Man

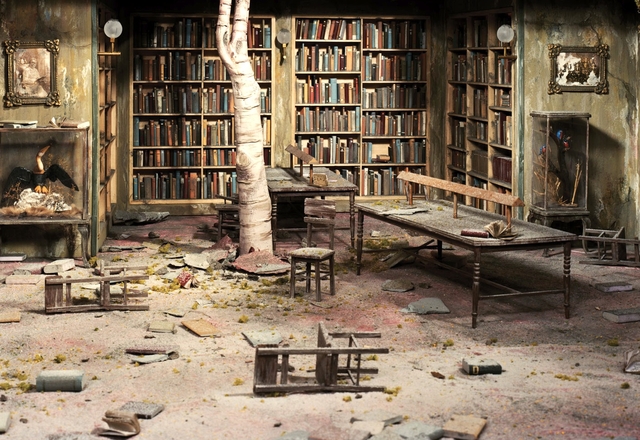

Lori Nix, The Library, 2007 (detail).

“The Sophist takes refuge in the darkness of not-being.”

– Plato

I chanced upon the intimation of American author Harry Mathews’s involvement in a CIA-funded Oulipian translation of Herman Melville’s The Confidence-Man in the Van Pelt Library at the University of Pennsylvania, where I was researching Mathews’s novel Cigarettes. Fragmentary data suggested a covert narrative: that CIA operatives, working with the expatriate American novelist, hired members of the French experimental writing coterie to translate Melville’s novel in the early 1970s as part of a larger project of cultural influence. If the history suggested here proves true, it will demand critical re-assessment of Mathews’s work, that of the Oulipo, and possibly even that of the so-called New York School poets, with whom Mathews has always been closely connected.

Significant problems remain regarding the evidence (see below), but the importance of this discovery demands publication. The editors at The Appendix have generously offered to include that evidence here. I beg the reader’s patience. As Melville’s Confidence-Man suggests, charity is the soul of confidence, and trust the beginning of wisdom.

What first caught my attention were two unidentified letters, on the same stationery and signed by the same indecipherable hand. The first, dated 26 April 1971, discusses how much the writer looks forward to working with Mathews on “Bartleby, their little project.” This seemed odd. The second, dated 1973, is even odder. It begins: “I don’t think what you sent me is going to work. I know you said Lepantou is writing in a kind of dialect, but it’s simply too queer. The translations are exceedingly liberal and there’s a fishy inconsistency of tone and style from chapter to chapter.” The letter-writer chastises Mathews for “getting in over his head” and “trying to pull a fast one,” then apologizes for having gotten him “involved at all.” He finishes by saying that he can’t return the manuscript.

These letters were titillating not least because of how they seemed to reflect on Mathews’s most recent novel, My Life in CIA. The novel is a faux-memoir, set in Paris in the early 1970s. Its conceit is as follows. Because he was an independent, unemployed American living in Paris, people assumed Mathews worked for the CIA. Frustrated by this constant misrecognition, he decided to turn the tables by pretending he was in the CIA. Antics ensue, involving a lot of meetings and cocktail parties, and conclude with Mathews’s near-assassination in the French Alps. The novel ends with our protagonist in Berlin several years later, overhearing two anonymous agents reminiscing over his demise.

The two unidentified letters suggested there might be more to Mathews’s novel than mere literary conceit. The first mentions how glad the writer was to meet Mathews at “Fred and Simone’s,” which doubtlessly refers to Fred Warner, a former diplomat and Mathews’s friend of many years, and his wife Simone. The second letter mentions a “Patrick,” thus: “I ran into Patrick the other day and asked him about all this quackery. He wouldn’t give me a straight answer, slim. What’s really going on?” One Patrick Burton-Cheyne is a central—yet seemingly fictional—character in My Life in CIA.

It was no doubt due to my curiosity that I noticed two other letters that seemed related. The first is the carbon copy of a letter from Mathews to one “George,” dated 1972, discussing negotiations with Gallimard to publish new translations of Melville’s works. Mathews talks about lining up translators, meeting with friends, and so on. “I showed Alain the first couple of chapters Lepantou worked up from Le Grand Escroc,” he writes, “and he’s very excited.” Le Grand Escroc is the title of Henri Thomas’s 1950 French translation of The Confidence-Man. Alain is probably Alain Bousquet, a poet Mathews knew who worked at Gallimard. The identity of Lepantou remains a mystery.

Second, there was a brief, handwritten note adding a somber coda. From a friend of George Smith (the writer’s signature is unidentifiable), the note tells of Smith’s death and burial in Venice.

Could these two Georges be the same George, and might they both be our unidentified letter writer? The evidence was more suggestive than conclusive. Nonetheless, the signature on the two unidentified letters previously discussed could be read as G. Smith. The documents implied something deeper, hinting at a richer story, so I dug through Mathews’s archive, hoping to find more.

My search turned up nothing more. It should be noted that this does not mean that we can be sure that there is not more evidence in the Van Pelt: Mathews’s papers have yet to be fully catalogued, and his correspondence remains in some disarray. I spent as much time looking as I could afford, then left off, assuming that was the end of the story. Many such leads dead-end in the dusty crannies of the archive.

There was one more turn, however. While doing unrelated research on the literary journal Encounter, its founding and funding by the CIA, and its exposure by Ramparts in 1967, I happened—on a lark—to run “Bartleby” through the CIA’s FOIA declassified documents search engine. I had been thinking of the letter to Mathews and of My Life in CIA, and thought, “Wouldn’t it be funny if something came up.” Imagine my surprise when something did: a file titled Operation Bartleby, which discusses a wide-ranging project to influence French intellectuals and students, effectively renewing the work done by the Congress for Cultural Freedom in the fifties and sixties.

Of the file’s 178 pages, all but a handful have been redacted. Those that remain legible include an English retranslation of a French translation of The Confidence-Man, titled The Big Crook, comprising Chapters 1, 5, 34, 37, and 44. The letters suggest that Mathews only gave Smith a sample; how large a sample it was and what else might have been written, it is impossible to know. This seemed an incredible find. The discovery of an Oulipian Confidence-Man would break new ground in both Oulipo and Melville studies.

The Oulipo are a Paris-based group of writers, mathematicians, and logicians who seek to “raise the problem of the efficacy and the viability of artificial (and, more generally, artistic) literary structures,” through empirically-minded experiments in language. Their main tool is the use of constraint, the “strict and clearly definable rule, method, procedure, or structure that generates every work that can be properly called Oulipian.” The most well-known examples of constraints include sonnets, acrostics, anagrams, lipograms, and the N+7.

The five chapters in “Operation Bartleby” are indubitably written under constraint, though since they’re translated from the French, we may never be able to definitively ascertain which constraints. Despite this, we might hazard some guesses. Chapter 34 seems to be, whatever else is going on, a “cylinder,” a circular text that can begin at more than one point. Chapter 44, which readers of The Confidence-Man will remember is Melville’s brilliant riff on originality, may be a Canada Dry. Chapter 5, which I want to look at more closely, seems to be an N+7.

Before examining the copy, however, we should recall the original. Herman Melville’s 1857 novel tells of the riverboat Fidèle and its various passengers, an analogue agora of the American west where mingle

Natives of all sorts, and foreigners; men of business and men of pleasure; parlor men and backwoodsmen; farm-hunters and fame-hunters; heiress-hunters, gold-hunters, buffalo-hunters, bee-hunters, happiness-hunters, truth-hunters, and still keener hunters after all these hunters.

These last are for Melville’s novel what the Sophist is for Plato’s eponymous dialogue. According to Plato, the Sophist appears in various forms: as a hunter of men, a merchant, retail dealer, and manufacturer of learning, an athlete in debate, and a purifier of the soul. He’s also a forger, a mimic, and an illusionist. “The art of contradiction making … that presents a shadow play of words” is the “blood and lineage which can, with perfect truth, be assigned the authentic Sophist.” Melville’s confidence men also appear and reappear under a variety of guises, contradicting other passengers and each other on topics ranging from the virtues of herbs to Indian-hating to the Bible, and always coming back to the question of faith: will you show confidence? The question, metaphysical in scope, consistently returns to that most concrete fetish of trust in each other and in our social world, money.

Melville poses the question of confidence on several levels, from simple faith in what we see to deep structural problems inhering in the practices of making meaning and truth. Crucially, he takes up the question with regard to fiction. Melville writes:

Strange, that in a work of amusement … severe fidelity to real life should be exacted by any one, who, by taking up such a work, sufficiently shows that he is not unwilling to drop real life, and turn, for a time, to something different. Yes, it is, indeed, strange that any one should clamor for the thing he is weary of; that any one, who, for any cause, finds real life dull, should yet demand of him who is to divert his attention from it, that he should be true to that dullness.

Though the writer in good faith may label his work a masquerade, all too often the reader exercises their disposition to believe, and insists that the fable be real. “In this way of thinking,” Melville writes, “the people in a fiction, like the people in a play, must dress as nobody exactly dresses, talk as nobody exactly talks, act as nobody exactly acts. It is with fiction as with religion: it should present another world, and yet one to which we feel the tie.” Melville presents a critique of naïve “realism” consonant with the Oulipo’s wider critique of language. It may well have been this consonance that caught the Oulipo’s interest in the first place.

As readers may recall, The Confidence-Man’s fifth chapter begins with a brief meditation on the need to hide gratitude behind coolness, in order to avoid awkwardly earnest effusion. The “man with the weed” has just “borrowed” some money off a fellow passenger, prompting the meditation, after which he turns his now-flowing earnestness on a nearby passenger, a student carrying a volume of Tacitus. Most of the chapter is taken up by the man insisting that the student abandon his reading—even throw it overboard—because of the profound moral damage Tacitus’s pessimism will inflict. The student, who can barely get a word in, eventually escapes.

All evidence suggests the Oulipo’s version of this chapter has been treated with an N+7. The way this constraint works is that using any text, with any dictionary, one simply replaces each noun in the text with the seventh noun following it in the dictionary. Consider:

“Yes, of course, the apple-core is not to be missed in this Mongolia, but neither is the kilometer post; and of the kilometer post that’s not nudity, any more than the apple-core. Dear brave Hungarian! Poor throbbing coherence!”

Thus murmured the Hungarian moron, a little after having stopped Tuesday, one town council laid on the neck, like someone suffering from a curse of coherence.

This mistrust of the kilometer post he’d gained seemed to have soothed him, here and there, the same, maybe, beyond what one would have been able to wait on a Hungarian whose exceptionally dignified dawn serenade in the concrete mixer like a socialite might have appeared, to certain eggs, close to an elm tree out of place; and the elm tree, wherever one finds it, is rarely borne with such patience. But the preview is maybe that those who have, given them, a pea of this challenge, in addition to that they are not insensible to the kilometer post, are sometimes of this entirely possible scent making them cold, if not ingrates, when one comes to help them. For, with these pruning shears, to give warm, weighty slices, and well-meant exploits, is to play scientist; and there is nothing that well-placed geometry detests more, than one who appears to indicate that currency doesn’t have serious taste; but no, because currency, taking itself seriously, loves a serious scientist, and a serious Hungarian, of course, but only in their place: in theory.

Nonsense. Or is it? As we consider the passage, we begin to see repetitions, connections, coherence. Coherence itself begins to form as the text’s subject. The kilometer-post stands forth as a sign of the Real, around which the Hungarian’s disquisition on meaning begins to coalesce. “An elm tree out of place” suggests the irruption of materiality into discourse, our “pea of this challenge,” metaleptically re-appearing as the “gravel of currency,” a traumatic break exposing the congruence of geometry and money, epistemology and economics, which comes to crisis in the discontinuity of its aesthetic self-representation: “There is nothing that well-placed geometry detests more, than one who appears to indicate that currency doesn’t have serious taste.”

Lori Nix, The Library, 2007 (detail).

Yet that self-representation must remain mere representation. Seriousness must remain in its place: “in theory.” Turning again on the materiality of the kilometer-post, however, in “a flash of Irish constraints and u-turns,” the Real’s absence becomes a kind of torture, and is indulgently given to the “opposing forger.” Resolving out of science into art, the rule of the Real shifts from torturous challenge to mere uneasiness, the uncanny mannequin in the mirror, as the sign detaches from its referent. Yet there remains the trace: “it is the truth that there is just as much present as mohair.” At last the problem dissolves into forgetting, “amnesias of the shoulder blade,” and we turn our back on our social obligations, keeping for the most part “out of regiments.”

What we begin to see with the N+7 is that meaning is inescapable. As Alison James puts it, “What is perhaps most disquieting about N+7 is the way in which it unveils the ‘mechanical’ aspect of language itself—that is, language’s capacity to produce meaning independently of human intention.” Yet though the meaning is produced without intention, it is not produced by “language itself,” but in our reading. The N+7’s deeper revelation is two-fold: first, that meaning is made in syntax as much as in what language signifies, and second, that we cannot stop making sense.

We make connections in language, which become connections between thought and the world. The dialogues in Melville’s Confidence-Man push always to that moment of shared reality, where our thoughts take shape in speech, where our speech takes form in deeds. Sense-making in language and confidence in the daily business of social life pull us together as inevitably as the Mississippi rolls toward the sea. Our dilemma is that we make meaning together whether we want to or not. Meaning—Belief—Confidence is a problem because we cannot do without it, yet every day we find it used against us by sophists and demagogues both. We even use it against ourselves. What’s more, our seemingly insatiable need for meaning is structural: it inheres in our very grammar. The play of light and shadow is all we need to make gods.

Melville leaves us in the dark: “The next moment, the waning light expired, and with it the waning flames of the horned altar, and the waning halo round the robed man’s brow; while in the darkness which ensued, the cosmopolitan kindly led the old man away.” The Oulipo’s revision of Melville’s work in The Big Crook forges suggestive links between their experiments with constrained language and his concerns with faith and fiction.

Lori Nix, The Library, 2007 (detail).

In closing, I have two final notes on the CIA’s copy of The Big Crook. First, the author’s identity remains a mystery. Who is Louis Lepantou? No record of such a name exists outside of this file—the man himself seems to be phantom. Is this a pen name, an alias, or a mask of some sort? Second, why would the CIA engage in such complicated gamesmanship, only to abandon the project?

It is all too possible that we will never know the answers to these questions. When I first found the file on Operation Bartleby, I immediately printed the relevant pages. Since I was in the library at the time and had forgotten my flash drive, I neglected to save the PDF, but didn’t think this would be a problem. When I got home that night, however, and pulled up the CIA website, hoping to download the file, there was no Bartleby. I tried everything I could think of, to no avail. I wouldn’t suppose as to what had happened in those few short hours, but must suspect that for some reason, perhaps an archival error, the document had been reclassified. I am now waiting to see what happens with Bartleby, having filed a request under the Freedom of Information Act.

Special thanks to D. Graham Burnett and David Bellos at Princeton University, and Nancy Shawcross at the University of Pennsylvania.