Feet First: Walking in Houston

Between the Archives and the Streets

People told me that I shouldn’t just walk through Houston. But I was there researching the city’s history, literally studying its streets, and I wanted to know them.

I’d seen the Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps and highway plans. Noted how each year’s edition illustrated the slow transition from the solid outlines of homes to the dotted lines of proposed rights-of-way and then, with finality, to the heavy stripes of expressways. I needed to see the spots in the city where those lines ran off the page. The world I walked through—between the archives, the libraries, the universities—complicated my vision of Houston. The city’s past collided with its concrete and steel now.

The warnings I heard about walking through the city didn’t come wholly from worries for my safety as a pedestrian. Some were you-just-don’t-want-to-walk-on-the-wrong-side-of-the-track glances from folks who’d lived in Houston for years. From white people, looking out for one of their own. “Don’t walk on the northside.” “Be careful in the Third Ward.” I didn’t heed them. I didn’t want to find blank spaces in my memories. I wanted to push against what those warnings left unsaid.

Noon on the northside looks a lot like noon in every other part of Houston, it turns out. The light rail is under construction on North Main Street. I cross into the neighborhood by walking through the Judge Alfredo Hernandez tunnel. The archives say the tunnel is an example of the engineering triumphs of the early 1900s. Dozens of train tracks above, four lanes of road below, yearly floods avoided, few accidents. The change in temperature, from sun to dark, raises goosebumps. The sudden darkness leaves me blinking. The tunnel smells like tunnels smell: piss and damp concrete. The pedestrian pathway is raised above the road surface hidden behind thick concrete pillars. I don’t linger.

Out into the sun again. Detour signs point traffic away from the rail line. I hop onto the concrete traffic barriers placed over the sidewalk and walk along them towards Poppa Burger, an old drive-thru that could have been a set for Happy Days. The light rail construction probably hasn’t helped business. There are thirteen of us there while I eat. Two older men. A family of seven. Myself. Three workers—two cooks and the cashier. I was told I couldn’t walk here, but heard I had to eat here: the cognitive dissonance between nostalgia and assumption. I eat to a soundtrack of soft voices and cooing pigeons. The French fries are delicious. I look out at the city where one doesn’t walk.

Discovery Green, Downtown Houston

Moving through a city on foot can be connective, but it also feels intrusive. Some paths, like the Columbia Tap rails-to-trails bikeway, a route that cuts through the center of the Third Ward, open into backyards and once-private porches. Views once afforded only to the closed eyes of freight cars and to bored teenagers balancing on the tracks. Such pathways disorient. Homes and businesses open towards the street, not the old rail line. Approaching the buildings from this angle is like introducing yourself to someone by placing a hand on the small of their back. The view from behind is more intimate. Some homes have chipped paint or sagging sashes. Others, tiny gardens and neatly arranged patio furniture. One resident placed a plank bridge across the ditch from the pathway to the gate of their wrought iron fence. Two or three bikes rest against the bars, ready. Still others seem to be boarded up against the eyes of the walkers and riders that pass them by. High fences. Shuttered windows. Signs that ward off the eyes of passersby.

The north end of the rails-to-trails path comes towards downtown Houston and passes near Discovery Green, a park space in front of the city’s main convention center. The park has only been in existence for a decade. Prior to the lake and the amphitheater, the playing field and the dog park, it was two parking lots for the titanic George R. Brown Convention Center. Prior to the parking lots, the land stood at the heart of Texas Eastern Corporation’s grand design for a modernistic city center—a 1960s vision plucked from a Bel Geddes scale model—replete with monorails, skywalks, and underground traffic flow. In the humid days of early summer, the Green buzzes with activity. Its jumping fountains pull hundreds of Houstonians in from the hot streets. The space is democratic. Where lines of Chevrolets and Fords once waited for their office-working owners to return, parents now chase toddlers across the playscape. The present overwhelms the landscapes of the past.

Fifteen or forty years from now the Green might be gone. Perhaps a new parking lot, a hotel, or a highway will stand where the Green is now. A scholar, studying shared social spaces or downtown redevelopment, might sit at a table in an air-conditioned archive and peruse the collected history of this place. A glossy magazine article, a laudatory speech, and photographs of happy families watching a Charlie Chaplin movie on a lazy summer evening.

From collected documents we draw pictures of history, ignoring what lies outside of our lines. The actors we encounter solely in the archives often seem to be cardboard cutouts, destined to repeat the same prerecorded message over and over. All we hear from them are their quotes in the newspaper or a testimony delivered to the City Council. The vagaries of action and reaction, the motions and emotions of the speaker are only rarely displayed in the record. In the archives the situation is controlled. The pages can be turned. The folder can be closed. The box can be ignored.

Back on the Green, ice cream melts and runs down the hand of a small child watching dogs wrestle in the fenced-off play area. The stickiness shines, unrecorded for posterity.

Summer Street

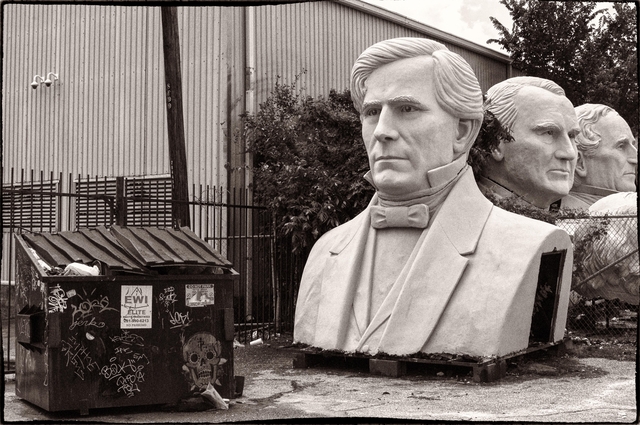

When you turn off of Sawyer, warehouses funnel you towards a gate at the western terminus of Summer Street. All at once they come into view. Forty or so vague shapes. Fallen smoke stacks? Abandoned tractor-trailers? Vague silhouettes stretch away from a chain-link fence.

Once you reach the gate, the shapes come into focus. Faces, not industrial castoffs. Crafted, not abandoned. Thomas Jefferson’s head is at least twice my height. Andrew Jackson’s could be three times that once you count his well coiffed hair. All forty-four presidents are there in various conditions of disrepair. Some need replastering. Others, a face lift or just an adjustment of their bowtie. At the back of the property a forty-foot version of the Beatles towers over the former heads of state. The storage yard abuts a train track. While no passengers get to inspect the bald spots of our nation’s leaders, at least the engineers of the oft-passing freight trains have a chance to glimpse Millard Fillmore’s head through George Harrison’s legs.

These plaster molds sit outside the warehouse of sculptor and artist David Adickes, near downtown Houston. The work in the yard forces history, art, and present-day Houston together. To find it, you have to walk or drive into the heart of the once-bustling industrial core between Washington Avenue and the Katy Freeway. The workspace stands surrounded by dozens of warehouses that look just like it. It sneaks up on you; at first you think you are on the wrong street. Only your arrival under Teddy Roosevelt’s mustache signals you’ve found Adickes’ building.

But Houston’s industrial past, a past that brought the grain silos and rail tracks to Summer Street, is transitioning. Not just to house art workshops and galleries, but to the new trappings of urban living. Two blocks from cement plants, trucking platforms, and sculpted leaders lies a Super Target, a luxury apartment building, and a Payless Shoes. Peaked and rusting roofs of tin and galvanized steel give way to flat-topped shopping centers and humming climate control. I walk through this evolution, my thoughts divided. James Madison’s smirk, the passage of time captured in the changing pallet of Washington Avenue’s businesses, and the pieces of this part of Houston’s history that I’ve come across in the archives all swimming in my vision. It’s hard to tell whether the city is coming or going. It’s impossible to see which parts are being erased, which are being drawn for the first time.

Sig Byrd’s Houston

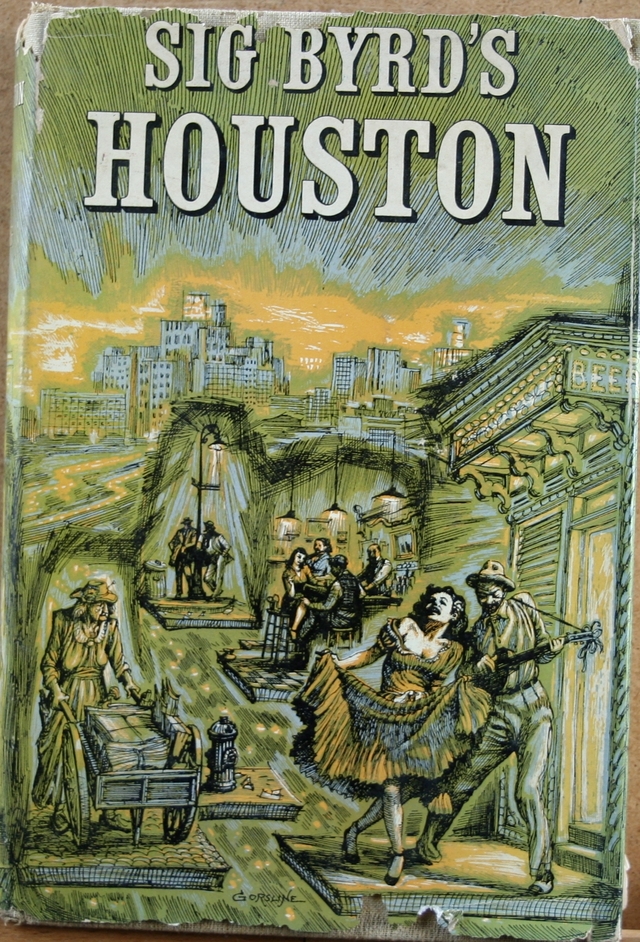

Sigman Byrd walked these same streets as a reporter for the Houston Chronicle in the 1950s. Monkey-bit. Gafftop. El Jefe. Greasy Smith. Byrd filled his columns with the characters that populated Houston’s grimier side. He walked through places with names like Catfish Reef, Pearl Harbor, and the Big Casino. He stopped, talked, and jotted at cantinas, beer joints, and flophouses. He talked of businesses come and gone and of drifters who had drifted on. His articles weren’t for the people who lived in Catfish Reef. I doubt the men, like Handsome Easley, who dodged cops and tried to scrape out a living in the Fifth Ward, had time to read the four column inches devoted to their story. This was voyeur journalism. Byrd wanted Houstonians living in River Oaks or Sharpstown to know that in the heart of their city a body could “get faded, get your picture made, your shoes shined, your hair cut, your teeth pulled. You can buy lewd pictures, and in the honkytonks you can arrange for the real thing.” Far from their tree-lined, gentle suburban streets, the avenues of downtown Houston offered “quietly cruel streets, where rents are high and laughter comes easy, where violence flares quickly and briefly in the Neon twilight, and if a dream ever comes true it’s apt to be a nightmare.” Byrd wrote of these places so his readers could learn their city without stepping through its streets.

The cover of Sig Byrd’s Houston (1955) showed the hard-luck characters that populated Houston’s juke joints, cantinas and flop houses.

Are my walks any different than Byrd’s? What about the words I write? Who do I write for and what type of city am I presenting?

My Houston is built by archives and walkabouts. Seen through my eyes and subject to my interpretations. Like my scholarship, my experience of Houston passes through my own set of expectations, fears, and knowledge. I spent only eight months in the city. Can I make claims about its past and present? Or does my brief stay make my views an illusion? How many will read me and think, “this guy doesn’t know Houston at all?” Do I sensationalize like Byrd? (I am trying hard not to.) Or are there universal parts of Houston somewhere in these phrases, as there were in his? I’m not sure that the Houston I’ve painted is the Houston others know. It is a city littered with memories. Snippets of documents and facts. Old facades and new developments. People I’ve watched on the streets and traced on paper. I’ve walked through all this and I’m still not sure I know how to find my way.

Marguerite Johnson Barnes Collection, Woodson Research Center, Rice University

Allen Parkway opened in the 1930s. Back then it was called Buffalo Parkway, named for the bayou that ran alongside of it. It carried Houstonians from downtown out to the then-developing, but already trendy, Memorial Park area. Dr. Sam Adams grew up in the all-black Fourth Ward just south of Buffalo Bayou and west of downtown. In the 1920s his family moved a few blocks further west and established a home just below the bayou. At the time of their move this was the outskirts of the developed city. A young Adams recalled playing in the wild growths alongside the water and running home through forests. Shooting turtles off logs and watching flood waters rise and recede. In the late 1920s and early 1930s the city began to build a road. The Adams’s neighbor hitched up a mule team and pulled clear the stumps as others hacked away at the bayou’s underbrush. The muleteers sang instructions and helped grade the surface. The macadam top eventually gave way to asphalt. The two-lane road to the six-lane Allen Parkway.

The Gregory School, the city’s first black elementary school, is now a library. An archive of Houston’s black history. It sits in the old Fourth Ward. New Houston is creeping in around it. Colorful, metal-roofed condominiums. A several-hundred unit apartment complex. But pieces of the former life remain: across the street from the Gregory School sits a large mostly-vacant lot. A few shotgun houses in various states of falling squat inside chain-link fences. These old homes, new, or at least newer, when Dr. Adams was a boy, now wait for historic renovation. They’re boarded up against the weather and the curious. Raised up on cinder block foundations. Raised up against floods and the passage of time. The Gregory School protects the records of these houses, the stories of families. The photographs of front porches and church suits. It documents rising downtown skyscrapers and sinking next-door homes.

Down the street is Founder’s Memorial Cemetery, a registered Texas Heritage Site. It’s the resting place for several heroes of the Texas Revolution and one of the founders of the city of Houston. Few, if any, of the families whose lives are documented at the Gregory School were buried here. Their cemetery lies west down Dallas Street another mile. They lived their lives a stone’s throw from Heritage. Many of their homes still wait for historical markers.

I walk through the Fourth Ward. Past a midday church service. Past the cemetery and the Public Storage Warehouse. I aim my feet towards the bayou. Walk the same ground that Dr. Adams would have walked as a child. I break through the neighborhood. He broke through the underbrush. We reach the water’s edge. My way is clear. Stands of trees mark the remnant of the forest Adams played in. I walk on an exercise trail, an asset for a livable city. I am meant to walk here. With the city’s natural history, its one unchanneled bayou on my right. With the city’s economic pulse, a string of high-rise businesses, a Whole Foods, and a branch of the Federal Reserve on my left. This path runs alongside Allen Parkway. It’s asphalt. Laid by heavy machines, pavers, rollers. Laid without singing—or at least without mules. I am meant to walk here. A white guy in tennis shoes, out to keep in shape. I am meant to walk here. A historian tugged between the new and the old, the read and the seen. Don’t go to the northside, don’t go to the Third Ward. Walk by the bayou, see its public art. Use the pedestrian bridge, not the overpasses. Walk on the bayou trail where the city’s past/present/future frame your sight and roll forward together like the languid water of the bayou towards Galveston Bay.

I roll forward. I close my eyes, straining to pick out the shouts of mule drivers from the hum of passing cars. A biker whizzes past me on the path. I look over my shoulder for others. At the water’s edge I see Dr. Adams taking potshots at painted turtles.