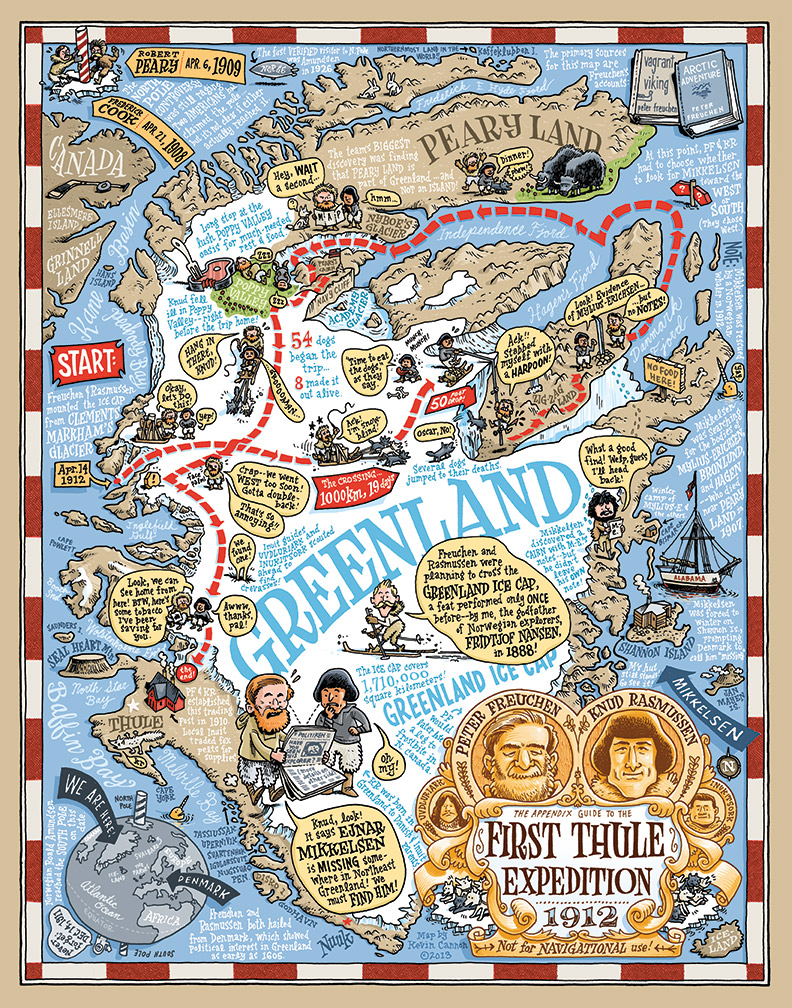

The Appendix, Appendixed.

Cold Cartography:

The First Thule Expedition to Greenland, 1912

Kevin Cannon knows his science history. As one half of the Minneapolis-based cartooning studio Big Time Attic, Cannon has co-illustrated graphic histories of evolution, the space race and bickering paleontologists in the American West. On his own, he’s the creator of Army Shanks, a hard-drinking pirate, former member of the (fictional) Royal Canadian Arctic Navy, and star of two largely hilarious and surprisingly moving graphic novels, Far Arden and Crater XV. Kevin Cannon and the other half of Big Time Attic, Zander Cannon—no relation—built up a buzz for Crater XV and Zander’s new work, Heck, with an ambitious digital project named Double Barrel.

Impressed by the Double Barrel initiative and knowing Kevin’s interest in the history of exploration, The Appendix reached out to see if he might have a comic history to contribute. He did us one better and proposed a “cartographic biography” of a little-known Danish explorer named Peter Freuchen who explored Greenland, lived with the Inuit, lost a leg to frostbite and, in one disastrous episode, claimed that he dug himself out of an ice cave with a knife formed of his own frozen excrement. Freuchen’s life turned out to be too rich, in fact, so Cannon hunkered down to create a cartographic chronicle of the First Thule Expedition, in 1912, in which Freuchen and the Inuit-Danish explorer Knud Rasmussen traveled a thousand kilometers across Greenland’s inland ice by dogsled. “I think polar exploration had gripped me because of its grittiness and lack of sexiness,” Kevin explains. “There are no Jack Sparrows in polar exploration.”

The beautiful and wry result, this issue’s ‘The Appendix, Appendixed,’ bookends the conversation this issue started with our ‘Open Source’ on the Cempoala map of sixteenth-century Mexico. Similar to the Cempoala map, a very local representation of an indigenous community, Cannon warns readers that the map is his personal interpretation of events, meant to

excite and inspire people who—like me—once viewed Greenland as a big ice-covered rock. Real historians and cartographers will note that besides the obvious fact that the scale is completely off, certain place names are incorrect as I used Freuchen’s account more than modern maps. Due to space limitations, I was also forced to leave out certain anecdotes, like Freuchen’s dive underwater to fetch his lost theodolite or the fact that Freuchen himself was on the Mylius-Erichsen expedition that started the whole chain of events in the first place.

For those stories, he recommends Freuchen’s memoir, the terrifically titled Vagrant Viking. In the meantime, we hope you get lost in Greenland with Freuchen, like we did.