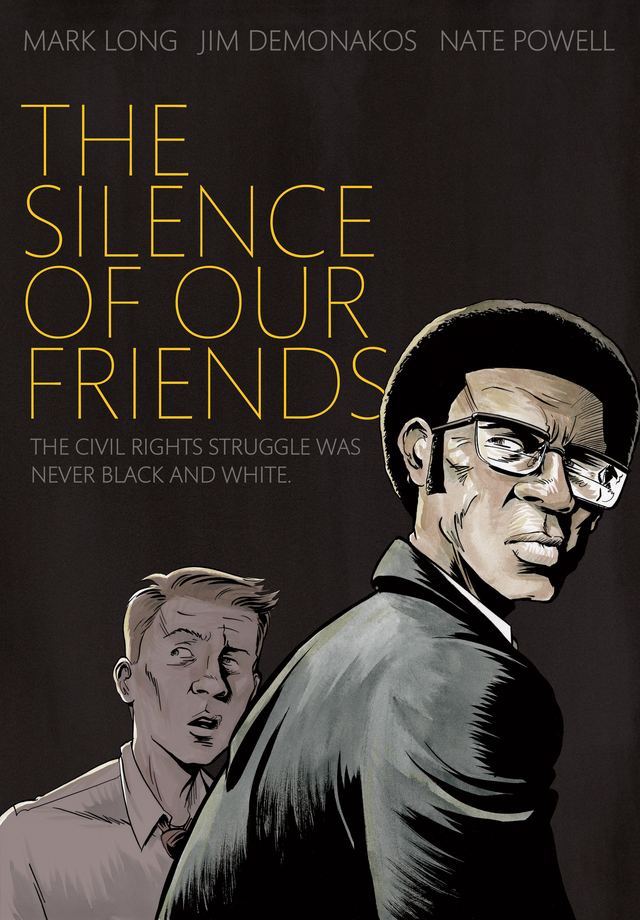

The Silence of Our Friends

Elsewhere in this issue of The Appendix, we interview Nate Powell, the illustrator of March, Congressman John Lewis’s graphic memoir of his life and fight in the Civil Rights movement, and excerpt from its pages. This wasn’t Powell’s first foray into the racial history of the American South, however. In 2012, First Second Books published The Silence of Our Friends, his collaboration with co-authors Mark Long and Jim Demonakos on a memoir-like novel about Long’s childhood in 1960s Houston. In the wake of March’s wide media success, Appendix local history editor Hannah Carney turns back to The Silence of Our Friends to explore how it navigated that similar terrain of history and memory.

The story begins in suburban Houston, 1968: a wide, empty street, power lines stretching to the horizon, neat low-slung ranch houses with evenly clipped lawns, a big car with flashy fins. A young white boy crouches behind a bush, pretending to creep up on a Vietcong soldier. After some shouting and mild blackmail, he lets his sister join in. Later they join their mother and watch the now-infamous footage of the execution of a Vietcong soldier by Vietnam’s Chief of National Police. Their earlier game suddenly seems less playful. The boy stands glued to the screen, and his sister comforts their horrified mother.

It’s a moment of intense foreshadowing: in the months to come, the family’s father will become involved in a more homegrown episode of police violence, when a peaceful protest of black students in Houston ends in a hail of police bullets and a landmark court case.

The friendship between the boy’s father, a white journalist named Jack Long, an African American Texas Southern University professor named Larry Thompson, and their families lies at the heart of The Silence of Our Friends, a recent graphic novel based on a little-known chapter of civil rights history. Its author, Mark Long, grew up in Houston in the 1960s and experienced much of what happens in the novel. Jack Long is based on his father and Thompson is based on a black activist named Larry Thomas. Together with co-author Jim Demonakos and artist Nate Powell, Long uses the graphic novel format to craft an authentic and believable re-creation of his memories of the not-so-distant past. The result is a deeply moving, often unsettling portrait of American racism as compelling for adults as it is for high school history classes.

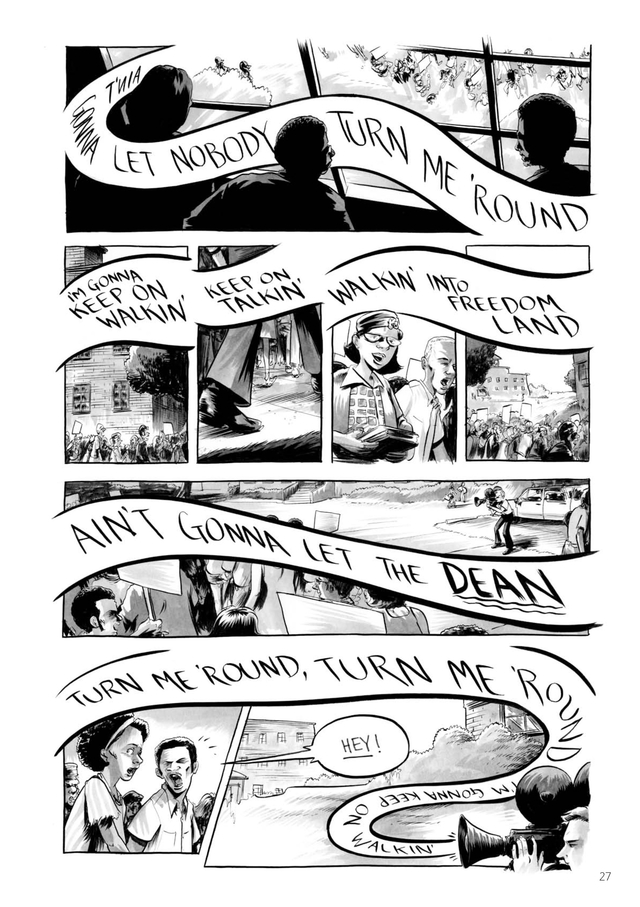

In the graphic novel, Long meets Thompson while working as a television reporter in Houston’s Third Ward. During a protest to allow the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee on TSU’s campus, Thompson stands up for Long when a group of African American students threatens to take away his camera and kick him off campus. Long is the only reporter in Houston who tries to provide balanced coverage of the Third Ward, a predominantly black neighborhood, and its student protests. As the leader of those protests, Thompson risks a professional alliance with Long that becomes more personal as they introduce their families to one another.

The graphic novel crescendos with two intensely-charged scenes that test the relationship between these two men and demonstrate the ugliness and violence of segregated Houston. The first begins with a nonviolent student protest on the TSU campus that is met with escalating police brutality, from billy clubs to pistols and machine guns fired at unarmed black students in a university dormitory. During that violence, a Houston police officer is killed, and the novel reconstructs the trial of five students accused of having shot him.

Powell’s illustrations bring the protests and trial to life. They evoke a palpable sense of the violence: police march in formation like soldiers, heavily armed with pistols in holsters and rifles slung across their backs. Billy clubs come down on the bodies of protestors on the ground: KRAK! THUD, THUMP. The authors cut from the scenes of repression to Jack Long behind the camera, his inert lens filming the growing violence. Powell leaves the scenes viewed through Long’s camera in pencil, uninked, their faint glassiness mimicking the television screens on which all of this will later be aired. This effect creates an interesting distance that makes the brutality feel more real.

Jack is both within the violence and without. The police hit him with a billy club and yell at him to leave. He stays, and amidst the chaos he sees Larry fall and get beaten by the police. Larry calls out to Jack for help, but the reporter instead retreats under a breezeway with other officers and keeps filming. The noise and violence seem less insistent for a moment. Jack has fulfilled his role as a journalist, but he has also betrayed his friend.

During the book’s second climax, the trial of the five black TSU students wrongly accused of killing an officer during the protest, Long’s testimony of the event proves crucial—showing that the officer was shot accidentally by a fellow cop. The scene, however, is the novel’s weakest moment. According to the author, Mark Long, it’s the only part of The Silence of Our Friends that is not based on a true account of what happened to him, his father, or Larry Thomas: neither Thomas nor Long was involved in the trial. Long explains, “We used the trial as a way to bring the antagonists and protagonists together, and very deliberately made it the climax, because it would be an opportunity for the characters to articulate in an elevated sense their motivations.” It indeed feels deliberate, but it doesn’t benefit the book.

Long, Demonakos and Powell do a better job showing characters’ motivations in the small, quiet scenes that make up the rest of the book. One evening at the Long’s house, Mark’s sister Julie tattles on her brother and says that he went “nigger knocking”—ringing doorbells and then running away. The parents are horrified by Julie’s casual racism, as unsettled as the reader by how easily Houston’s greater racism—the family had recently moved there from less-segregated San Antonio—seeps into their children’s lives and becomes normalized.

When asked about the scene, Long explains that “a big theme in the book is the violence of language.” The use of the word “nigger” and “that kind of banal, everyday, insidious racism” the word implies are more important to understand, says Long in an interview, than the “mean sheriff who might as well be a Nazi.” It’s not just the Bull Connors we should study and talk about. It’s the ordinary people who go about their lives, oblivious or willfully ignorant to the ways that racism boosts them up and shoves people of color down.

Long and his collaborators are unstinting in their portrayal of white racism and Jack Long’s other flaws, which feel painfully real in the narrative. Before dying of cancer in 2009, Jack Long was deeply involved with the writing process and barely hesitated before signing off on the use of his former alcoholism as a key plot point. He had become sober long before, and had worked as a drug and alcohol counselor in Texas prisons.

Long tried to track down Larry Thomas and his family before writing the book, but he wasn’t able to locate them—the two families lost touch sometime after the sixties. It’s hard not to wonder how the novel might read had the two men kept in touch, and had Thomas contributed his own perspective during the writing of this story.

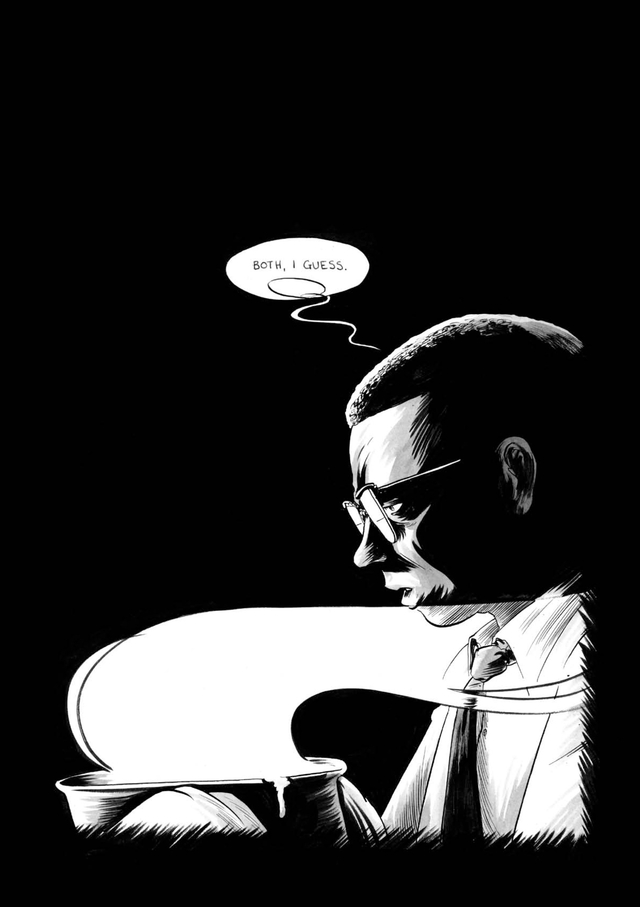

Still, The Silence of Our Friends rings true in its portrayal of the initial wariness of a friendship between a black and a white man in Houston in 1968. In one scene, Larry Thompson and his wife Barbara prepare dinner for their family. Larry tells Barbara that he wants to invite Jack over to their home, and Barbara objects; African Americans didn’t typically invite white people into their homes at this time in Houston. She asks whether Larry wants to “use [Jack] or be friends with him?” On a single page with a black background, Larry stands in profile and answers “both, I guess.”

In a corner of popular history that sometimes resorts to heroism and cliché, the nuance of The Silence of Our Friends offers a deeply personal take on the impact of racism in our country, and is as relevant for students as it is for adults. With hard-won realism, the graphic novel ends not with the conclusion of the TSU Five’s trial but with the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. In a beautiful sequence of panels, Powell illustrates a march in King’s honor. Long and Thompson—or Thomas—walk beside each other along with their families. The two men join hands. A final haunting quotation from Martin Luther King gives the book its title and turns Long and Thomas’s friendship over for scrutiny one last time:

“In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”