Calypso’s Island: A Short History of the Apocalypse

Mesopotamia, circa 2000 BCE:

Orphans of Ur

O my flooded, washed away

Brickwork of Ur!

My good house, my city,

you who have been piled in heaps,

As I lay myself down with you

in a breach in your good ravaged house,

I shall, like a fallen ox

never be able to rise again.

– Anonymous, “Lamentation over the destruction of Ur,” c. 2000 BCE, from Thorkild Jacobset, The Harps that Once…: Sumerian Poetry in Translation, 447-8.

How does one survive an apocalypse, let alone remember it? Who writes the history of the end of the world?

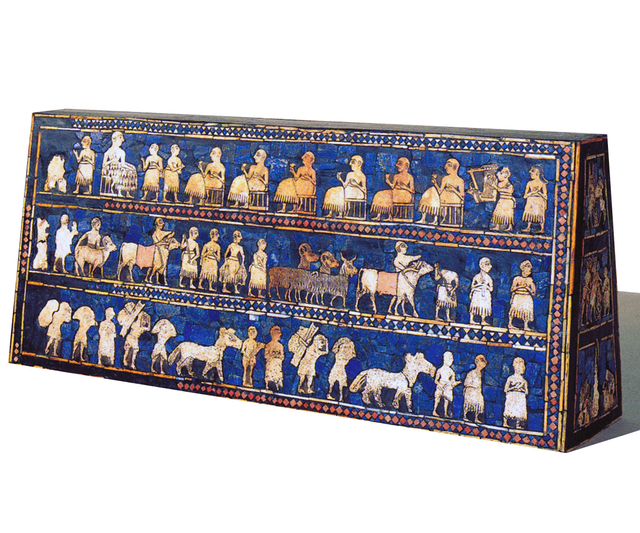

At the time of its destruction four thousand years ago, Ur was the largest city in the world. Indeed, up to that point, it was the largest city to exist in the history of the world. Having emerged as an agricultural settlement in the late Neolithic, Ur’s citizens gained nourishment from barley, onions and emmer wheat coaxed from the fertile black soil of the Persian Gulf floodplains. As its power grew, conquered neighbors sent gold, silver, lapis lazuli, incense, sheep and slaves as tribute. The Kings of Ur enforced the earliest known code of laws, prescribing rules for everything from slave marriages to the proper punishment for false accusations of sorcery. Ur’s scribes created some of the earliest known written records. One could make a convincing argument that Ur invented Western civilization.

In 2004 BC, soldiers from the emerging empire of Elam in present-day Iran overran the city’s fortifications and killed or enslaved many of its citizens. For the inhabitants of Ur, it truly was the end of the world – or, at least, of their world. Remembering the disaster decades later, the survivors produced some of the earliest poetry in the historical record. These poems are dark lamentations, frightening, violent and nihilistic in tone. They speak of the night air filled with “burning pieces of clay” and of terrorized townsfolk “crouch[ing] down at the wall,” the Elamites “chewing them up/ like a pack of dogs.” The gaps and destroyed spaces in the text itself mirror the erasure of Ur’s society:

O city of […], you have been destroyed.

O city of [high walls,] your land has perished.

O my city, like an innocent ewe your lamb has been torn away from you;

O Ur, like an innocent goat your kid has perished.

These poems are the earliest post-apocalyptic narratives. They document a world that would never exist again. The Sumerian language spoken in Ur was what linguists call an “isolate”: a tongue with no known relatives and no modern-day speakers. The culture that gave rise to farming, cities and writing became submerged beneath repeated invasions—Elamite, Akkadian, Assyrian, Persian, Greek—until eventually it was all but forgotten, even by those who inherited it.

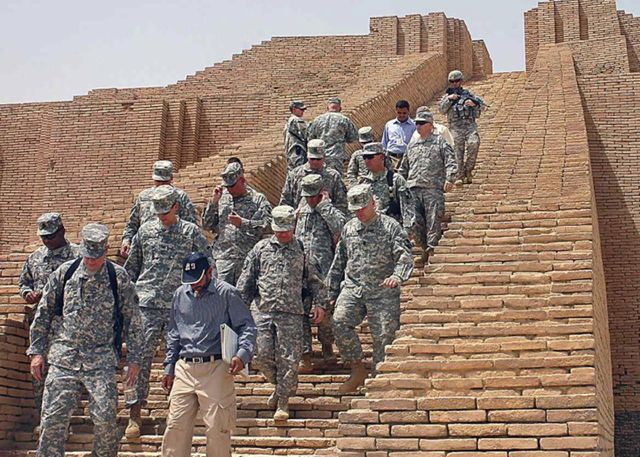

And yet we can write about Ur today. This is apocalypse’s central paradox. If we define apocalypse as the ending of existence, writing its history becomes impossible: no one would remain to realize that nothing remained. In practice, though, world-endings have had survivors. There are men and women living in the ancient Sumerian heartlands – the governate of Dhi Kar in Iraq, to be precise – who are direct descendants of the people of Ur. Indeed, some of them may well have labored to rebuild Ur’s great ziggurat during its reconstruction under Saddam Hussein. The rebuilding took place during the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, a strange re-figuration of the Sumerian-Elamite wars that had led to the temple’s destruction 4,000 years earlier.

Brigadier General Michael Lally and Col. Dan Hokanson, joined by other US army officials, tour the Ziggurat of Ur on July 31, 2009. Photograph by Spc. Cory Grogan. Used under Creative Commons license (CC BY 2.0). (Via the official US Army Flickr page.)

In a real sense, though, Ur did die. Ur’s patron diety—Nanna, the lunar god of wisdom, depicted as an old man with a flowing beard of lapis lazuli—was forgotten. Followers of Marduk, Ahura-Mazda, Yawheh and Allah worshipped their foreign gods upon the ruins of his shrines. The apocalyptic destruction described in the lamentations for Ur was real.

Apocalypse, however, is a strange and ambiguous word. Deriving from the Greek apokalyptein, or “uncovering,” its present-day meaning of world-ending disaster is underlain by an older connotation of revealed knowledge or illumination. An apocalypse is both a knowing and an unknowing; it is the end of history, yet also the revelation of new information. Apocalypse both buries and unearths.

San Diego, 1997:

Heaven’s Gate

I want you all to know that I was a member of Heaven’s Gate from 1994-1997. I know everything worth knowing about them and I can say with absolute, undeniable certainty, that Heaven’s Gate was indeed “The Second Coming of Jesus.”

—Rio Diangelo, sole survivor of Heaven’s Gate, as published in LA Weekly, March 21, 2007.

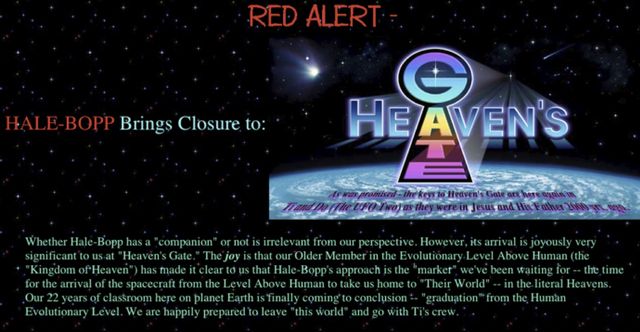

San Diego, California witnessed another form of apocalypse in March of 1997. The Heaven’s Gate cult believed that their bodies were mere ‘vehicles’ for an eternal spirit that would move to a more evolved plane of existence upon leaving its physical container. The cult leaders proclaimed that year’s Hale-Bopp comet to be the sign they had been waiting for: just before the comet reached its perihelion on April 1, 1997, thirty-nine cult members ate overdoses of phenobarbital in apple sauce and laid down to die in their San Diego mansion.

There was only one survivor: Rio DiAngelo. DiAngelo came so close to joining the rest of his “class” in their “departure,” as the Heavens’ Gate members put it, that he had a uniform prepared for his final moment on earth. Yet at the last moment he chose to survive so that the cult’s message would be passed down.

Splash page from heavensgate.com, a website made by the members of the Heaven’s Gate cult in 1997 and maintained on web servers even after their death by the mysterious Teleh Foundation.

In April of 2012, a reporter in Las Vegas spoke briefly with someone who may or may not be Rio DiAngelo. This person claimed to be a representative of the Teleh Foundation, an organization that continues to maintain the Heaven’s Gate website some fifteen years after the death of every member of the cult besides DiAngelo. Although this source insisted that the Heaven’s Gate cult members were “the finest… individuals that were on this planet,” the anonymous representative was highly critical of the apocalyptic beliefs surrounding the date of December 21, 2012: “Our own opinion is that it is a bunch of nonsense. The world will still be here on December 22.”

Surviving an apocalypse is a lonely business. Yet in a sense, there can be no apocalypse without a survivor. It was DiAngelo who discovered the bodies of his fellow cult members. He filmed the macabre scene with a camcorder, following directions that the cult’s leader had sent to him in a UPS package. And DiAngelo continues to uphold its teachings – the final survivor of a religion that collectively chose to end its own earthly existence. “I am alive,” he wrote in 2007, “because I have discovered something so extraordinarily important to the world that it needs to pass on to you in its most true and accurate form.”

Like the survivors who lamented Ur, Rio DiAngelo is an orphan, irreparably cut off from the context that made his life whole. Yet they are also witnesses, and in their act of witnessing they join the ranks of those who survived. Their lives are split between endings and beginnings, between knowing what came before and what came after.

Winter, 1811:

Comet Vintages and Failed Apocalypses

“I arrose [sic] and beheld to my great Joy the stars fall from heaven, yea, they fell like hail stones: a litteral [sic] fulfillment of the word of God as recorded in the holy scriptures and a sure sign that the coming of Christ is close at hand.”

– Journal of Joseph Smith, 1833, in reference to the great Leonid meteor shower of 1833

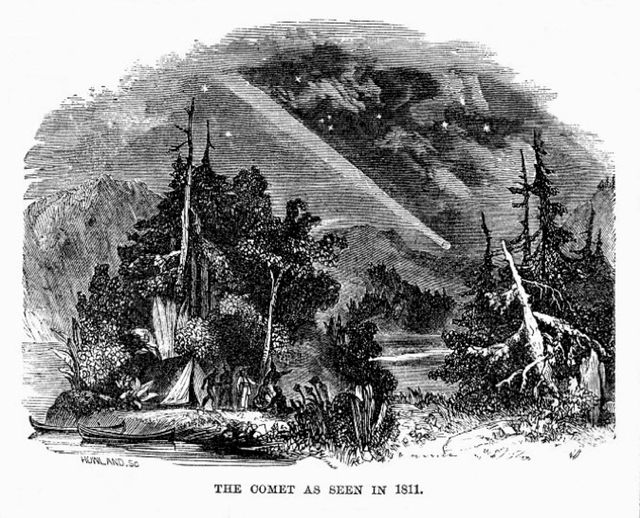

Stargazers in the fall of 1811, gazing to the northwest in the hours after sunset, would have beheld a luminous, hazy object whose light seemed to increase with each passing night. In early October, an Ohio newspaper reported that its glowing center was “obscured by a dense Atmosphere” and quoted a local savant who claimed that the approach of great comets altered the earth’s “subterraneous waters,” thereby warping the earth’s shape from “a spherical to an oval figure” and causing fossils and bones to be deposited in the depths of the earth. The article warned that comets such as these were “generally attended with extraordinary tides and tempests.”

Temperatures dropped that winter and the new comet’s hazy light grew brighter and brighter in the night sky. Earthquakes, droughts, and even unexpected military defeats seemed to augur a change in the natural order of things. Comets and other astral phenomena had figured in the apocalyptic imaginary since the time of Ur, when early cuneiform prophecy manuals first associated Mars with the God of War, Venus with the Goddess of Love, and comets with famine, disaster and war. In some cases – such as in the destruction of Ur – these earliest written prophecies were hauntingly accurate.

Yet the early nineteenth century – an age of millenarian prophecies and societal upheaval – showed what happened when predicted apocalypses failed to arrive.

“The Comet as Seen in 1811,” Merry’s Museum, (New York, 1858), Vol. 35, pg. 127.

Across the Atlantic from Ohio, in Western Europe, the victorious soldiers of the French Empire lauded the heavenly apparition as Le Comète de Napoléon (“Napoleon’s Comet”). 1811 had marked the apex of Napoleon’s power, and he apparently deemed the comet a sign of divine favor. It is debatable whether or not the appearance of this cosmic harbinger actually influenced Bonaparte’s decision to mount his disastrous attempted conquest of Russia, as is sometimes claimed – but it is at least the case that contemporaries thought it did. For Pierre, the hero of War and Peace who mounts a doomed attempt to assassinate Napoleon, this comet presaged great changes: under its pale light, he falls in love and enters “a realm of beauty.” An acquaintance warns Pierre about an apocalyptic prophecy that our hero conflates with the appearance of the comet and his own future:

Writing the words L’Empereur Napoleon in numbers [according to Hebrew numerology], it appears that the sum of them is 666… This discovery excited him. How, or by what means, he was connected with the great event foretold in the Apocalypse he did not know, but he did not doubt that connection for a moment. His love for Natasha, Antichrist, Napoleon, the invasion, the comet… all this had to mature and culminate, to lift him out of that spellbound, petty sphere of Moscow habits in which he felt himself held captive and lead him to great achievement.

For Napoleon himself, the comet was instead a harbinger of disaster: the Russian Campaign he launched in the months following its appearance killed 380,000 men out of his force of half a million and led to the downfall of the French Empire.

For the most part, of course, the comet was not read as a true sign of apocalypse, but merely as a signal of great events: Pierre toys with prophecies from Revelations, but his focus on his future success makes it plainly evident that he didn’t actually expect Napoleon’s Comet to usher in the Second Coming. Nor did the French: even as Napoleon was leading his Grande Armée to ruin, French winemakers were crafting a celebrated vintage—the “Comet Year” wine—that eventually yielded one of the most expensive bottles of wine ever sold: the 1811 Chateau d’Yquem, which fetched 75,000 pounds in 2011. Clearly the winemakers who harvested, barreled and aged this vintage—famed for its longevity—were looking forward to a long future.

Meanwhile, in Lexington, Kentucky, an anonymous newspaper reporter took stock of the cosmic significance of the “very severe shock from an Earthquake” that hit what was then the American west—the trans-Appalachian backlands and river valleys that had been newly purchased from the French by President Jefferson. As the article noted, Mother Nature “had been prodigal in the exhibition of her phenomena, during the present year.” The earthquake briefly caused the Mississippi River to run backwards, tornados had “ravaged the continent from Maine to Georgia,” and the ocean itself was disturbed by “Volcanic terror” that had created new islands. The reporter believed that the “fiery Comet [which] has for many months appeared in continual view” had presaged these apocalyptic events, which the reporter believed were signs that God, “in spasmodic fury,” could “no longer tolerate the moral turpitude of man.”

Echoes of Sumerian prophecy in the land of bourbon and horse races. Americans of the early Republic were every bit as fascinated by the symbolic meaning of astronomical portents as the people of Ur or the UFO cults of 1990s California. Indeed, Mormonism itself was born in this ferment of apocalyptic astronomy.

Owing to the phenomenal success of their religion in the twentieth century, we tend to envision Mormonism as exceptional and unique. Yet Joseph Smith’s Latter Day Saints were only one group among dozens of small, fervent congregations that formed around charismatic leaders during the era of the Second Great Awakening. Moreover, mainline Protestant observers of these sects in the 1830s were far more preoccupied with the followers of one William Miller than those of Joseph Smith. The reason for their worry was simple: Miller and his followers, the Millerites, believed the world would end on October 22, 1844.

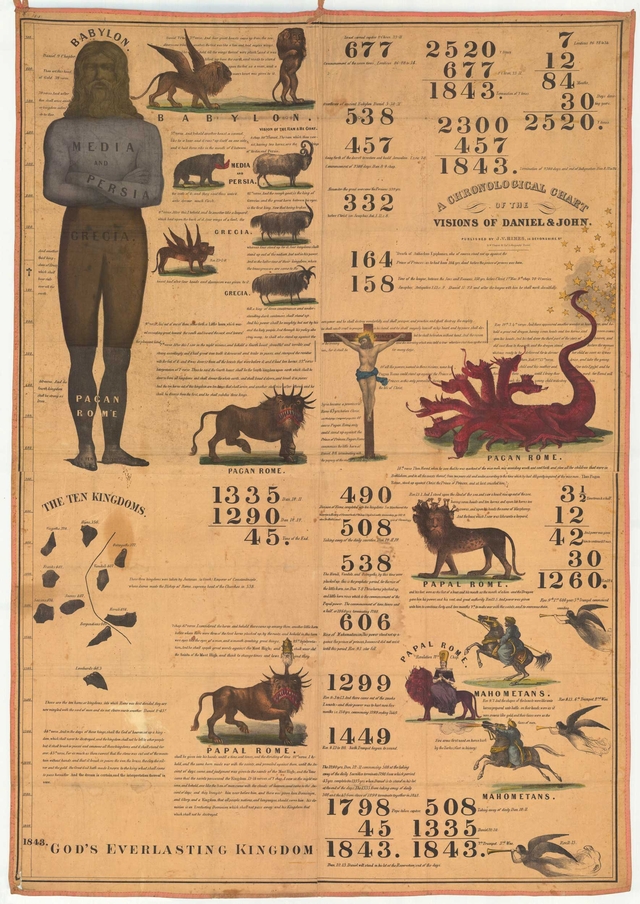

Millerite prophetic chart from 1843, from P. Gerard Damsteegt, Foundations of the Seventh-day Adventist Message and Mission_ (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 1977), 310.

The appearance of a new comet—one bright enough to be visible at high noon—in the spring of 1844 seemed to signal the truth of Miller’s prophecies. Yet the day of reckoning itself, October 22, was a disappointment. Miller was said to have appeared on a hill wearing white robes and preaching, but Christ did not appear. One follower, O. J. D. Pickands, conjectured that the Savior was floating on a cloud above them and needed to be coaxed down via prayer. The remaining Millerites didn’t vanish.

As described by historian Rachel Ozanne in the supernote accompanying this paragraph, many continued to hope for the return of Jesus. One branch of Millerites began to claim that something fundamental had changed on October 22, 1844: Jesus, they believed had “entered the heavenly sanctuary.” This group would become the Seventh-day Adventists. Apocalypses can lead to unexpected beginnings.

Escaping Calypso’s Island

I saw him once on an island, weeping live warm tears

in the nymph Calypso’s house—she holds him there by force.

He has no way to voyage home to his native land.

– The Odyssey, Book 4, Robert Fagles translation

In The Odyssey, Homer’s eponymous hero is tormented for seven years by Calypso, a goddess who inhabits an enchanted island called Ogygia. The Roman writer Plutarch speculated that this island lay “far out at sea, distant five days’ sail from Britain,” in the same region as Atlantis. Homer himself was more vague, calling it an “island worlds apart,” abundant with vines, violet-studded meadows, clear springs, and groves of alders, poplars and cypress that sheltered “owls and hawks and the spread-beaked ravens of the sea.” At the heart of the island, covered over with vegetation, lay a hidden cavern where Calypso tended a blazing hearth of cedar and sweetwood. Here she sang a song of enchantment while weaving endlessly at a golden loom.

Calypso’s name came from the Greek word kalyptein, to cover or conceal. She was a hidden immortal, a magic-worker and holder of secret knowledge who lived beneath the earth. Perhaps originating as a primeval goddess of death, her name shares a root with both ‘cell,’ which entered medieval English as a description for a monk’s chamber, and with ‘Hell’– the ultimate concealed place beneath.

It is also the antonym of the word “Apocalypse”: Calypso conceals, apocalypse reveals.

In order to carry news of Calypso’s enchanted island to mortals, Odysseus had to escape, to survive, and to remember. So too do all refugees of apocalypse. To know the history of the end of the world is to survive it. Escaping Calypso’s island is the process that carries history along, hopefully unending, even as the End of History is proclaimed anew by each new generation and each new culture. Like Odysseus, we all want to go home, despite the fact that the home we left is not the home we return to. There are beginnings in these endings – even as we throw glances over our shoulders at the many who never escaped.

The author would like to thank Rachel Ozanne for her assistance.