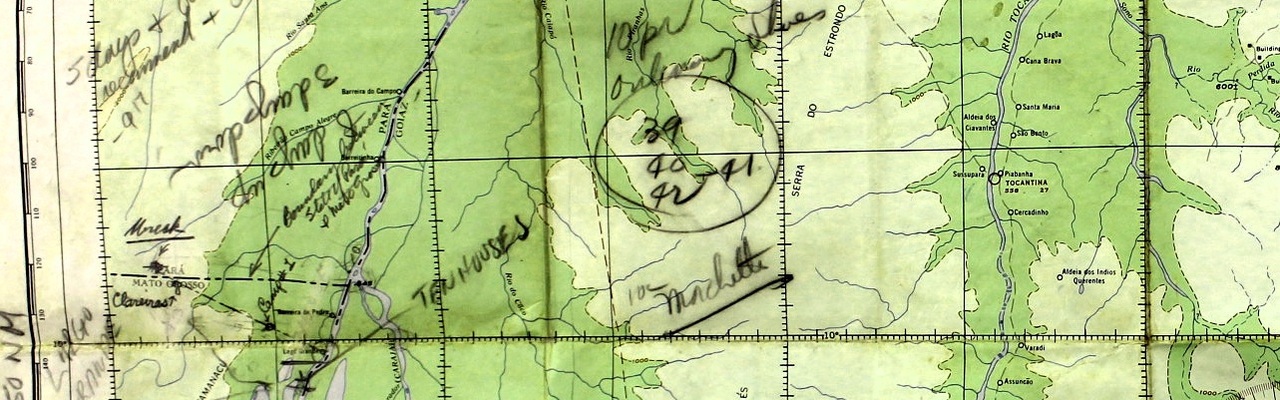

Map used by the land expedition to find the wreckage of PanAm flight 202.

Map used by the land expedition to find the wreckage of PanAm flight 202.

Amazonia 1952: FOUND

It was a fall morning, but hot enough to make me sweat. As I climbed into the library elevator, the frigid A/C gave me a chill. Par for the course in Miami.

Ding. Eighth Floor—Special Collections. I left the elevator, greeted the friendly librarian and sat down for another uneventful day of browsing corporate documents from the PanAmerican World Airways collection. I asked for a yet another cardboard box full of memos, charts, letters and clippings, and then arranged the tools of my trade on the sterile black Formica desk. I sat back down. Looking out the window southwards, over the ocean towards Cuba, I let my thoughts drift.

Like the PanAm clippers that once flew south from Miami carrying wealthy passengers into exotic fantasies promised by travel posters, I was looking forward to Brazil. I should have been there by now, but bureaucratic barriers had delayed me from that phase of my research. Instead, I was in this modern office building, biding my time while my friends hurried to more exotic places and stranger archives. They sat in colonial prisons in Mexico City, imperial counting houses in Sevilla, and museum closets in Washington, sorting through obscure alchemical texts, sailors’ diaries, letters from revolutionaries, and even shelves full of pre-Columbian skulls.

Miami was exciting, but I had lived in Florida for many years and was ready to ship off for my own tour of archival duty. I was anxious to visit collections all across Brazil—imagining it as a frenetic adventure, as if Jack Kerouac had been an archive rat in On The Road. I was feeling a historian’s version of wanderlust.

A squeaky cart carrying five boxes rolled around the corner, interrupting my daydream.

This was a five-boxes-at-a-time kind of archive. Within the five delivered on the cart was a treat: some battered aviation maps that had needed care from the document restoration specialist before reaching my gloveless hands. I picked box number nine, and pulled out the first item, a thick manila envelope with the phrase “Jungle Episode 1952” written across the front.

I arranged it gently on the desk, as if I were handling a relic. I opened my camera’s shutter. Click. And then I opened the envelope.

A raucous pack of wild boars exploded from the jungle. It was a dark evening in early May, 1952, near the Araguaia river in the eastern Amazon. The expedition’s members—Carajá Indians, Brazilian workers and PanAm employees—scrambled into the trees and waited as hundreds of menacing tusks passed beneath them. It was just one of the many hazards they faced as they hacked through thirty-six miles of dense rainforest to reach the wreckage of PanAm flight 202.

On the night of April 29 1952, PanAm flight 202 had failed to report at one of its radio checkpoints between Rio de Janeiro and Port of Spain. It never arrived at its destination, Port of Spain, from whence it would have continued north to New York City. The search planes went up, and on the morning of May 1, one spotted a fresh clearing in the dense jungle. There it was—the charred wreckage of a Boeing StratoCruiser, last seen taking off Rio’s Santos-Dumont Airport with forty-one passengers and nine crew members aboard. After circling the site for hours and seeing no survivors, the search plane’s pilots decided there was no point in risking more lives by launching their team of parachute paramedics. They returned to their base in Belém and started making plans for a ground expedition.

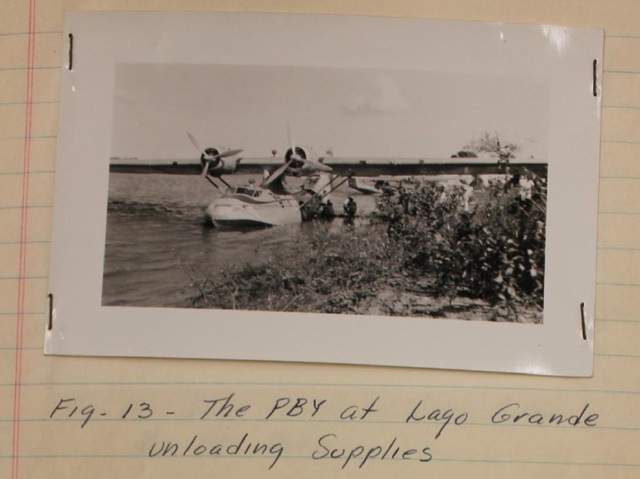

Brazilian and North American air force officers and crash investigators, along with representatives of PanAm, scrutinized the maps and decided to land an amphibious airplane as close to the crash as possible, at the village of Lagoa Grande on the Araguaia River. Once there, they arranged a staging camp and asked for the help of the Brazilian “Indian Protection Services”—the bureaucracy charged with controlling interactions between outsiders and indigenous peoples. The agency sent one of its officers along with a group of Carajá Indians to serve as guides. They set off as soon as possible. It would be tough work. They would have to hack through thirty-six miles of dense forest. With trees rising over a hundred feet tall and casting a permanent shade, they were not cutting a trail: they were a digging a tunnel through the forest’s thick underbrush.

That night in early May, as the wild boars finally passed, one of the Carajás leapt from his treetop shelter to fell one with an arrow. Dinner was better than the usual military ration that night, but the team kept moving at a grueling pace. They had other threats to worry about. As wet as the Amazon seems, this area was a hard place to find potable water. The expedition often relied on drinking water collected from vines and leaves while one of the Carajás ranged ahead searching for streams.

Even maintaining their sense of direction was difficult, and without radio equipment, so was communication with the outside world. They received instructions from the main camp by airplane. If the cutting party heard an engine, they would light a smoke signal (their trail was invisible by air), and the airplane would circle and drop a package with directions or other messages.

Back at the Lagoa Grande base camp, a second drama was unfolding. The official expedition realized that they were not the only search party out there. Further survey flights revealed parachutes on the nearby treetops. Another group of rescuers was already walking around the wreckage! The morning papers confirmed it: an independent group of paratroopers, financed by the boisterous ex-governor of São Paulo, Adhemar de Barros, had parachuted directly into the crash site. A tawdry war of words began. Barros was planning to run for President of Brazil in the next election and the official expedition accused him of grandstanding, launching his own operation for political gain. Barros shot back, arguing that there might be survivors, and the Americans lacked the courage to reach the site by parachuting in from their airplanes.

Humphrey Toomey was the director of PanAm’s operations in Latin America at the time, and it fell to him to coordinate the official rescue operation from Lagoa Grande. He sent a letter to the Brazilian Air Force in Belém, pleading for them to intervene and stop the rogue expedition. The authorities agreed, but the parachutists were already on the scene. Toomey was afraid that they might disturb the wreckage and ruin the investigation. Perhaps he paced around the camp anxiously, then turned to one of the mechanics that PanAm had flown in from Miami, asked for a match, and lit a cigar.

Or at least that’s what I think he did. Back in Miami, 2011, right as I pulled Toomey’s letter to the Brazilian authorities from the musty envelope, a matchbook fell out onto the archive’s black table. It was from a Miami Beach bar named “The Lighthouse.” This “Jungle Episode 1952” envelope contained Toomey’s personal papers from the expedition, and included a number of other odd items, as if everything he had on him during the expedition had been shoved into this envelope and filed away by an assistant.

The matchbook, along with many of the documents mentioned here, can be seen by clicking through the supernotes to the right of each paragraph.

The matchbook seemed to have accumulated quite a few miles. Turning it over in my hand, I guessed that it was picked up by a PanAm mechanic at the Miami Beach bar, flew in his shirt or pants pocket to the heart of the Amazon, then was loaned to Mr. Toomey, who took it with him to Rio de Janeiro. Then, sometime after Toomey’s untimely murder in Rio de Janeiro, it flew back inside the envelope to Miami to become a part of the archival collection at the University of Miami. Before returning to Miami, it likely also made a stop at the corporate offices of PanAm in New York City along the way, where the archives previously resided.

The envelope contained quite a few interesting and mysterious items. One was a letter Toomey received from a psychic, claiming not only that were there survivors, but that he knew where they were. “He should go to a place (probably Indian village) called Gatatuaton where seven survivors will be found.” The psychic also warned that “he must return to Belém” because “the supposedly friendly Indians with him now, are not friendly.”

Another letter was more poignant, suggesting how the accident and PanAm’s recovery mission themselves crashed into the consciousness of the more hard-up residents in the area. In shaky handwriting, a farmer wrote a note to “Mr Toomey” claiming seven years of accounting experience and asking for a good placement at the PanAm offices in Rio de Janeiro.

Some were just sad, like the prepared script that PanAm provided to employees for condolence calls to the families of the victims. There were English and Portuguese versions of it, since many of the passengers were Brazilian: “This is _(name)_, of Pan American World Airways. I called you again to convey our continued sympathy and condolence and also because of our wish to reassure you that everything possible is being done to gain access to the location of and thoroughly investigate the accident.” At one point, the script instructs the PanAm employee to stop and listen to the victim’s family:

(AWAIT ANSWER AND MAKE WRITTEN NOTES AT THIS POINT, IF APPROPRIATE)

Sitting in the archive, I took some notes myself. They probably were not “appropriate.” Archival notes—the rawest form of historical analysis—are hardly ever “appropriate.”

Back in 1952 the investigation crew still had to deal with the competing expedition. With the paratroopers already in place, they decided to abandon the trail cutting enterprise (after days lost hacking through dense jungle) and fly directly to the crash site on a US Air Force helicopter that had just been delivered from Panama. After a few helicopter flights, the investigators set up camp near the parachutists from São Paulo. Tensions between the groups developed immediately, and only grew as supplies dwindled.

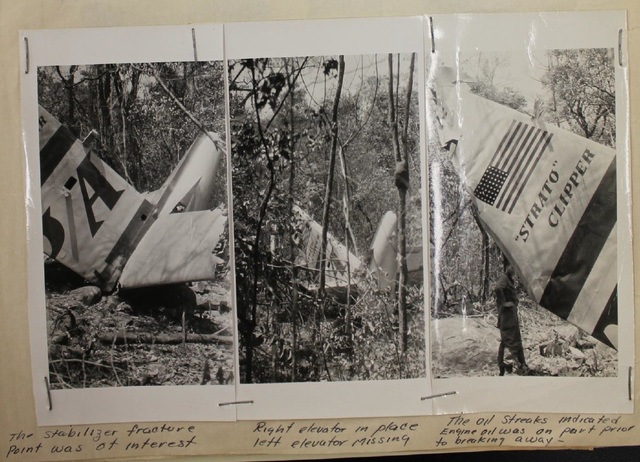

Meanwhile, the investigation began. The psychic had been wrong: there were no survivors. Air safety specialists sketched the layout of wreck, which helped them reconstruct the intricacies of the aerial accident. The way a metal cable was frayed, how an oil slick formed on a surface, or how a particular sheet of steel had torn were all valuable clues that hinted at what had happened and offered knowledge that could prevent future tragedies. Indeed, earlier that year PanAm flight 526A had made a successful water landing (technically known as ditching) near Puerto Rico, but many confused passengers could not leave the plane in the rough seas and sank with the plane. That very crash was the reason why passengers today receive detailed instructions on how to exit a plane and float in the case of a water “landing.” Hence the herculean efforts to investigate PanAm Flight 202: it could someday save lives.

It became clear that these were less than ideal conditions for a detailed technical investigation, however. Adhemar de Barros’ paratroopers hadn’t packed well. They ran out of supplies and there wasn’t enough water at the site for both their group and the official investigators. Without a trail back to home base, supplies could only be airlifted in by helicopter; because of the height of the trees, the helicopter had to lower the supplies with a rope that was not long enough. The delivery package dropped, rupturing its water containers. The PanAm expedition’s nerves were also frayed by the paratroopers’ technique for scaring off animals in the darkness: they threw grenades into the jungle at random hours of the night.

Making matters even worse, the helicopter, the team’s only link to the main camp, was suffering from a mechanical malfunction and only had a limited number of flights left. The official party made the decision to evacuate. They took their final notes and photographs, buried the bodies in a mass grave, and started leaving by helicopter.

Humphrey Toomey reads a prayer he prepared on the field, as they buried the fifty passengers and crew members. The handwritten notes seen in his hands can be read by viewing the notes for this article.

If only it were so simple. The paratroopers, with no way back, wanted a guaranteed ride out of the crash site. The American helicopter was on its last legs and could barely airlift the official investigators. One PanAm employee, irritated, later wrote in his notebook that when they asked “What about us?” he was tempted to reply, “You jumped in, why not try jumping out!”

Tensions reached a crescendo when the “Adhemar de Barros” expedition demanded that one of the Americans stay behind to ensure that they too would be evacuated. Scott Magness, from the US Civil Aeronautics Administration, and Major Miranda Correa, from the Brazilian Air Force, volunteered to act as collateral for the paratroopers—in essence, to become hostages. The helicopter pilot offered Magness an opportunity to covertly jump on the helicopter, but he pointed out that their Colt .45’s were no match for the paratroopers’ machine guns.

The story was already a media sensation in both countries. To keep the tragedy from tipping into a disgrace, the official expedition agreed to the deal. The American helicopter airlifted the rest of the investigators out, leaving behind Scott Magness, Major Correa, and the paratroopers’ second demand: a large power chainsaw. The paratroopers used the chainsaw to open a landing strip long enough for a small plane to land and ferry them out.

Their mission over, the official party radioed a message across thirty-six miles of forest to the main camp at Lagoa Grande: “Mission Complete. All persons dead. Recognition impossible, bodies buried, some personal effects recovered.”

“Some personal effects recovered.” Sitting in Miami, I felt chastened. I hadn’t yet considered the real people, and their belongings, at the center of this tragedy. The next archival envelope I opened made them impossible to avoid.

“Items recovered from Flight 202,” it read. It contained a half-destroyed five Franc bill, a pair of airmail letters, and a travel itinerary never completed.

The money, I later discovered, probably belonged to Lucie Marie Claire Pardieu. She was a French nun from the Sacre Coeur order, returning from a convent in Uruguay. There is a letter from the Sister Superior authorizing PanAm to bury her remains.

The airmail missives were also touching. In one, Richard Temple, in Jamaica, wrote to Lucy Wood, in Buenos Aires, to excuse himself for not sending little Anthony (their son) on a flight to spend the holidays in Buenos Aires. “I know how terribly disappointed you must be, but am sure that you will understand.” The boy was sick, and the doctor warned that his appendix might flare up. Anthony’s illness might have saved him, as he was not on the flight himself. Sadly, he might have also missed his last opportunity to see his mother. The letter was among many items belonging to Lucy found on the wreckage, including a Canadian passport, a certificate of good behavior from the Argentine government, and two valises. “Five cotton bunny heads” and “children toys” were also among the items recovered by investigators. I wondered if they had been presents Lucy was bringing for Anthony.

The list of recovered items written up by the investigators was a snapshot of the workers, the children, and the wealthy travelers who died together—toys, a smashed roll of Kodak film, a flight attendant’s lapel pin and union card, Uruguayan, Brazilian, Argentine, Canadian and English passports, thousands of dollars in travelers checks, calling cards, gold watch, a pearl necklace, a girl’s photograph…

There was also the travel itinerary for Mr. and Mrs. Heinel’s month-long vacation. They had travelled to New Orleans, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo, staying at various high-end hotels in rooms with “twin beds and a bath.” They had taken a steamer to Rio de Janeiro, and spent a few days riding the cable car to the Sugarloaf and enjoying the “marvelous city.” In Trinidad, they looked forward to a tour by “private car with English speaking chauffer-guide […] through groves of Cocoa, Nutmeg, Coffee, passing the Great Samaan, the most famous tree in the West Indies.”

They never saw the Great Samaan. Flight 202 stopped along the way.

It was 4:30pm and it was last call at the archive. I gently placed these delicate documents, moldy from their long layover in the heart of the Amazon, back in their box. The friendly librarian, Steven Hersh, placed them on hold so I could continue reading them in the morning.

I took the elevator down and walked out into a balmy Miami afternoon. I got in my car, and started driving aimlessly through Miami. I wondered if might stumble upon The Lighthouse Bar and Restaurant. If I did, I wanted to order bourbon, neat, and ask for some matches.