Mapping Babel: A Sixteenth-Century Indigenous Map from Mexico

Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

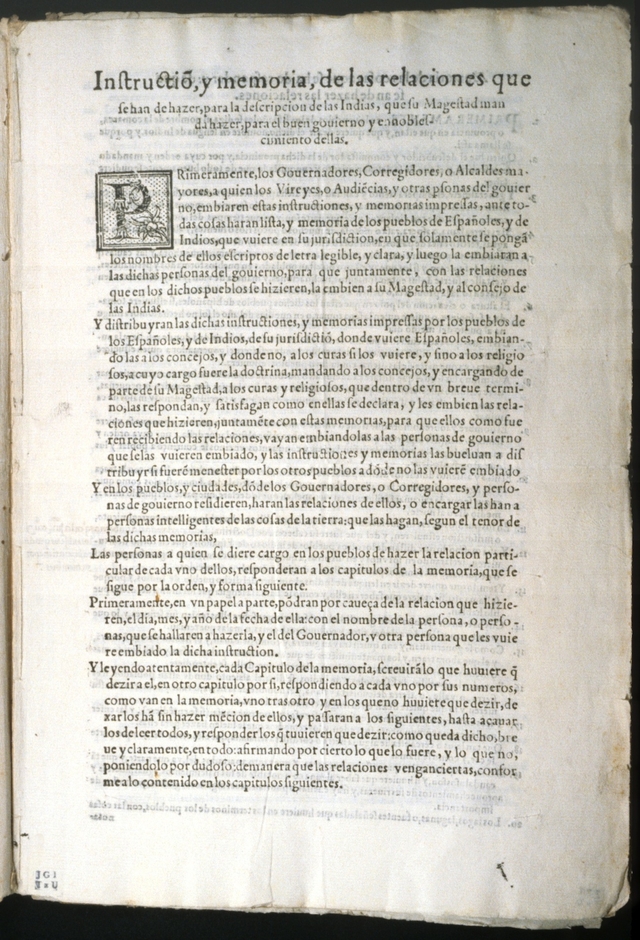

In the late 1570s, a printed broadsheet from the King of Spain was sent out to local officials in cities and towns in his American domains. In an itemized list, it asked for information about local climate, geography, history, economy, and religion—a proto-survey.

We can think of the questionnaire—with its bold heading, “Instructiõ, y memoria”—as the initial domino that set off a cavalcade of acts of translation, particularly in New Spain, the region encompassing modern-day Mexico and Guatemala. It passed from the central hub of the imperial bureaucracy in Mexico City out to crown officials in the provinces. There, they considered its fifty questions with care, and in indigenous majority cities and towns (there were many) they called native leaders into their office, often called the casa real. An interpreter translated the questions into Nahuatl, or Zapotec, or Mixtec, or whatever the common language was. If Europeans believed that the world’s once-unified language had broken at Babel and scattered across the face of the earth, then Mexico’s hundreds of indigenous languages sat at the extreme frontier of that linguistic diaspora.

In those Mexican casas reales, the replies were translated back into Spanish, set down in alphabetic script on expensive imported paper, carried back to Mexico City, and then shipped to Spain. Today, these replies, known as the Relaciones geográficas, are collectively the most important source for regional history in the sixteenth-century New World—their raw data translated into the clean prose of a historical text.

The printed text of the Relación Geográfica questionnaire, 1577. Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

The line of falling dominos, those translated questions and replies passing from one mind and hand to another, had an offshoot that began in the early set of exchanges in one casa real. Question ten asked for a pintura, a term that might be translated to tlacuilolli in Nahuatl, understood to be a map of the town or region. But the tlacuilo (the person who created the tlacuilolli) was more than a scrivener. Rather, he (and sometimes she) was understood to have the capacity to translate immaterial knowledge into visible form. Every act of putting a brush loaded with pigment onto paper was an inquiry into the nature of the world.

Cempoala region with rough area covered on the map or pintura of the Relación Geográfica of Cempoala highlighted. Google Earth

The pintura from the region of Cempoala is one of these acts of translation. It shows us a region to the northeast of Mexico City, and on the expanse of paper, measuring 67 x 81.5 cm, its creator has depicted a region of about 600 square miles.

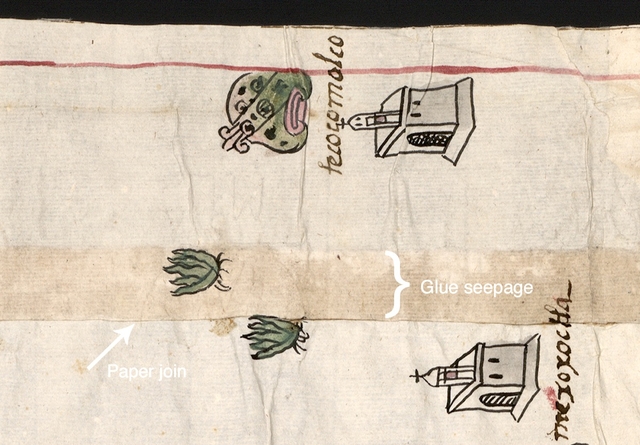

The first act of translation came with the material surface. Native paper was unsized and flexible, and native painters would pound together sheets to achieve the size appropriate to the object being represented. The Cempoala map was created out of imported European paper. Valued for its smooth surface, European paper came in set parameters. But rather than having their map conform to the standardized European sheet size, Cempoala’s artist(s) made the Spanish paper resemble its indigenous counterpart, piecing sheets together. The lines set on the image below mark the four large sheets, with two narrow additions across the top.

The map of the Relación Geográfica of Cempoala, with paper joins highlighted in white. Diagram by the author

The detail below shows where one of the narrow strips was attached: the slightly darker surface below the join results from the adhesive seeping through the paper. Why the modification? Was the map’s maker guided by an ideal set of proportions? Was s/he copying an extant map?

Relación Geográfica of Cempoala detail showing join of paper strips. Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

The paper shows one act of translation. But what were the others that took place to create the map? What other languages—the language of the body, the language of the sacred—found a place on its surface?

In our experience of the physical landscape, it is our mobile body that is the orienting pivot in space. Modern maps and landscape paintings demand that our body be static, fixed in space, viewing from one point, one orientation.

The Cempoala map, however, has no fixed orientation, and the presumed viewer is a mobile one, the body alive in space. To see the map, you must move around the work, reorienting yourself to its features. You must step back, away, to see the whole, and come close to see the hand of the painter, knowledge translated into paint.

Relación Geográfica of Cempoala, detail of Tepemaxalco. Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

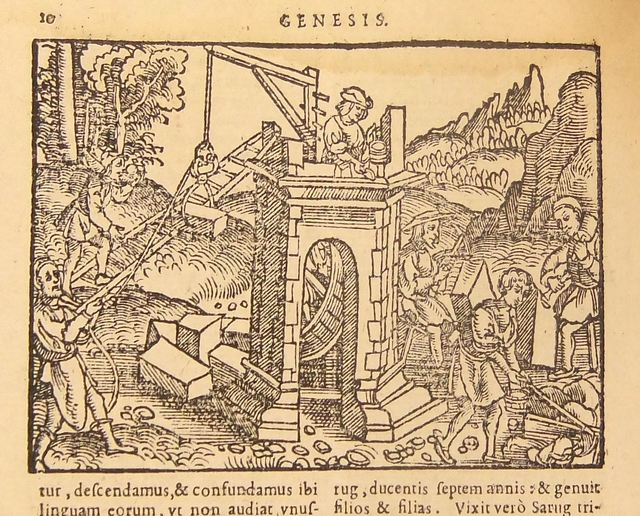

Seen up close, the map links image and word. The town of Tepemaxalco is shown—as are others on the map—with a conventional sign for a Christian chapel: a small building drawn in perspective with one side marked by a shadowing grey wash, topped with belfry and cross. This icon is itself a translation, almost certainly originating in one of the European prints that the native painter knew. Below is one such woodcut, set into a Bible printed in 1561 and imported to Mexico. In the scene from Genesis, the Tower of Babel is erected, and in the illustration, the basic conventions for rendering in perspective and shading are set out.

Unknown artist, The tower of Babel, from Genesis 11, Biblia Sacra, ex postremis doctorum omnium vigiliis (Lyon: Jacob de Millis, 1561), 10. Christoph Keller, Jr. Library, General Theological Seminary, New York, NY

Tepemaxalco registers the shattering of a common language in other ways. Across the map, names appear in both pictographic and alphabetic script. The pictograph for Tepemaxalco registers some of its Nahuatl components: tepetl, ‘hill,’ maitl, ‘hand,’ xalli, ‘sand’ and co, ‘place of.’ Below, the name is written in alphabetic script, probably introduced by the Franciscans who evangelized this region. The writer used both a different instrument—note the thin, sharp lines made by the edge of the pen’s nib on the ‘e’ and the ‘p’—and a different ink, iron gall, revealed by the rusty brown.

Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

The red pigment seen on the cactus fruit was derived from the crushed body of the cochineal bug, which feeds on the leaves of the nopal cactus. Red visually unifies the nochtli—the blood-red fruit of the cactus, likened in pre-Hispanic period to the human heart—and the bell of the church, a new sonic presence in this landscape, rung to mark a Mass or a death.

The place-name of Cempoala. Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

The signal act of translation is to be found in the place-name of Cempoala itself, which dominates the map. The name derives from the Nahuatl cempoalli, or ‘twenty,’ but this is not a logograph. Instead, it is an enormous bell-shaped hill symbol. The figure at the top is an indigenous noble, wearing discs of turquoise in his pierced ears and lip, his hair bound by a red leather strap. The artist revealed its deeper nature in this visual sign by covering it with the diamond pattern of the skin of the earth monster, Tlaltecuhtli, whose body had been ripped apart to create the habitable world.

The symbol’s central axis is dominated by another nopal cactus, and on this one three birds cluster. Easily identifiable are the nectar-loving hummingbird, to the left, and the owl. The bird on the right looks like a great blue heron, with the rusty legs of the heron translated to a pinkish underbelly here. An anecdotal nature scene translated from European landscape painting? Perhaps not. Instead, it may be a depiction of the great world trees that supported indigenous Mexico’s skies, at whose top perched a celestial bird.

Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

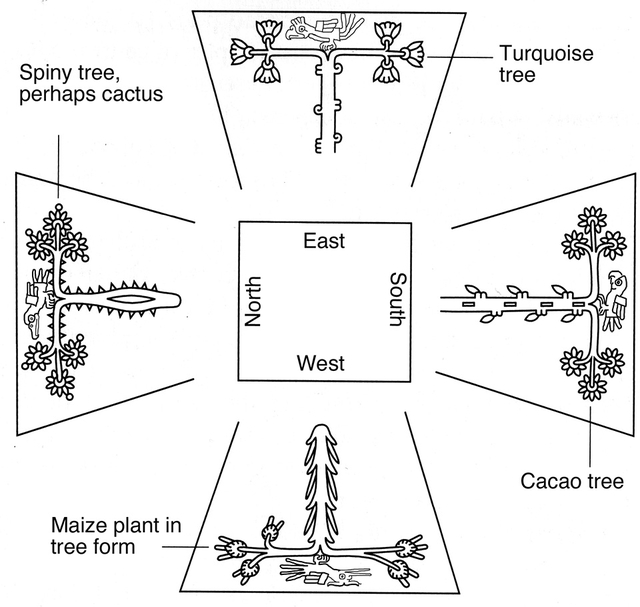

The image below is drawn from the diagram of the cosmos that opens the Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, a pre-Hispanic sacred manuscript. Here, in each of the four quadrants of the world, a bird sits at the top of a world tree. In Cempoala, it is unresolved why the artist represented three birds when one would suffice, but the inclusion of such a potent symbol within the place name shows the deep imprint of long-held spatial templates.

Drawing of the four directions of the world, after Codex Fejérváry-Mayer, fol. 1r., fifteenth-early sixteenth century. Diagram by the author

The map of Cempoala was a stopping point for that initial domino-chain of translations. Sacred ideas about the world were set in painted forms. Color-saturated pictographs settled down with alphabetic script. The features of the landscape were compressed and frozen on a flat page. But we can also see the Cempoala map as the starting point for yet further translations and transformations. When experiencing the physical landscape, the viewer stands at center, but in viewing the Relación Geográfica of Cempoala, the map itself becomes the central pivot in the encounter. And in the fragments of the map reproduced here on a computer screen—cut out and isolated from the larger whole, scaled up and scaled down—an encounter with the centuries-old object is translated afresh into a digital language.

Even today, the scattering across the face of the earth continues and new languages are born.

The author and The Appendix would like to thank Michael Hironymous and the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas, and Rev. Andrew Kadel and the Christoph Keller, Jr. Library for making their images freely available to a larger public.