Reclaiming a Fugitive Landscape

Introduction

Slaves were allowed three day’s holiday at Christmas time, and so it was over Christmas that John Andrew Jackson decided to escape.

The first day I devoted to bidding a sad, though silent farewell to my people; for I did not even dare to tell my father or mother that I was going, lest for joy they should tell some one else. Early next morning, I left them playing their “fandango” play. I wept as I looked at them enjoying their innocent play, and thought it was the last time I should ever see them, for I was determined never to return alive.

To run by day or by night? To flee on a road or in the woods? To rely upon subterfuge or unadulterated boldness? These were life-or-death decisions for a fugitive slave. When John Andrew Jackson fled a Sumter District plantation in South Carolina, he made strategic choices for his survival. He had a pony and rode mostly on roads, talking his way out of confrontations. Jackson gambled on his plausibility and charm. Most of all, he clung to a faith in his ability to mislead others with his own imagination. He crafted his own terrain.

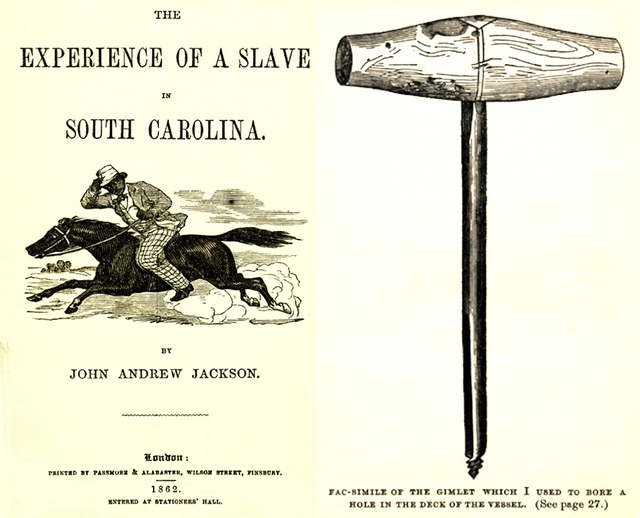

Jackson wrote of his escape in an 1862 memoir entitled The Experience Of A Slave in South Carolina. While his memoir was composed some fifteen years after his 1846 escape, many of the details Jackson recalled were precise. Some of them, though, represented a hazy dreamscape of horror—a perspective blurred by fear and despair. He sought, as he explained it, to see from above:

I may as well relate here, how I became acquainted with the fact of there being a Free State. The “Yankees,” or Northerners, when they visited our plantation, used to tell the negroes that there was a country called England, where there were no slaves, and that the city of Boston was free; and we used to wish we knew which way to travel to find those places. When we were picking cotton, we used to see the wild geese flying over our heads to some distant land, and we often used to say to each other, “O that we had wings like those geese, then we would fly over the heads of our masters to the ‘Land of the Free.’”

But Jackson’s flight from South Carolina did not begin with the furtive acquisition of a pony that allowed him to traverse 150 miles of roads, rivers, and swamps. Rather, it began with imagining the landscape from a bird’s eye view. It was Jackson’s ability to project a higher vision of his own relationship to the land, mentally flying from South Carolina itself, that enabled his more physical flight.

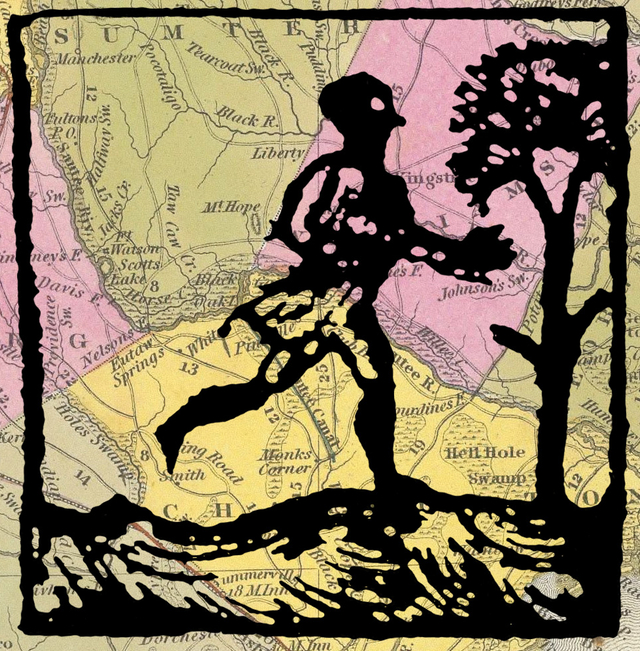

Jackson escapes his pursuers on horseback, from from his memoir, The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina (London, 1862). American Antiquarian Society

For enslaved people, geography has had a fraught and haunting significance. It resonates most powerfully in their memoirs but also glows in their interviews and recollections from later years. Whether slavery adhered to place or to the person was, of course, the question that framed the entire division of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America into ‘free states’ and ‘slave states.’ And worst of all, of course, were the ambiguous status of Kansas, Oklahoma, and the territories yet to be delineated in that cruel rubric of the antebellum period. How much did ‘place’ in the United States define citizenship, freedom and identity? Could one ever escape?

Jackson’s flight suggests a possible answer. If locale fundamentally defined identity, then one could assert the rights of citizenship or national identity by claiming one’s physical relationship to the larger land of America. Those rights were fragile, however, as Jackson soon discovered. The 1850 Fugitive Slave Act rendered slaves liable to forcible return to plantations no matter where they were, which effectively made geography within the United States irrelevant to one’s status. Under such a law, could a place ever be reclaimed or reoccupied under different terms by someone who fled bondage?

Could a person even buy back the land that enslaved them?

John Andrew Jackson’s flight and eventual return to South Carolina illustrate how one man worked out these questions not just logistically, but also imaginatively. At one point during his escape, Jackson was asked, “Who do you belong to?” With no easy answer at hand, Jackson replied simply, “I belong to South Carolina.”

For whatever reason, the retort satisfied the interrogators, who let him be. Jackson’s carefully-crafted remark, however, suggests how profoundly his identity was tied to his sense of place. As he continued in his memoir, “It was none of their business whom I belonged to; I was trying to belong to myself.” But before he could verbally sever his enslavement to the land, he had to do so physically. Jackson’s fascinating memoir shows us how he did so through a traceable, mappable flight—and then, after the war, how he reclaimed that landscape on wholly different terms.

The Flight from Sumter

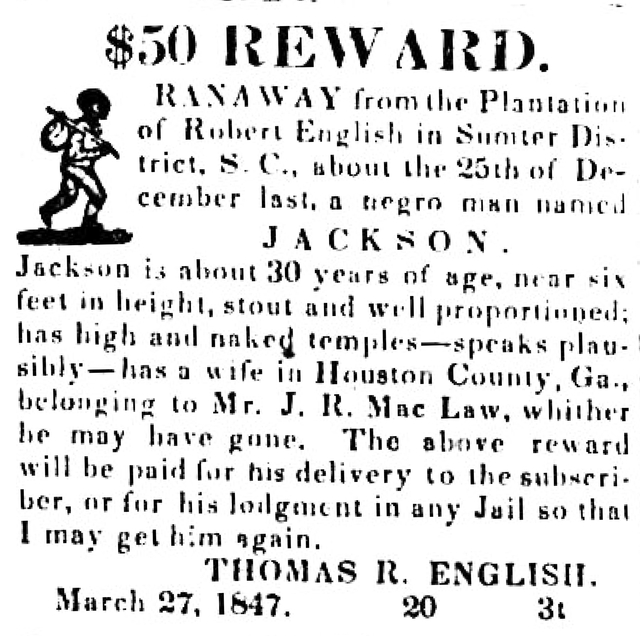

Although many accounts of runaway slaves from the antebellum South survive, the story of John Andrew Jackson’s escape is something special. Finding an advertisement calling for the capture of a specific person is rare in slave history, but we have found a detailed one seeking Jackson. We can use that advertisement alongside his own account of his escape, and our own geographical understanding of the region, to triangulate his multiple routes to freedom. Not only can his specific and vague references to landmarks help us re-imagine his route over rivers and roads, thus validating his claims, but we can also discover how freedom-seekers like Jackson manipulated their enslavers’ notions of flight.

In other words, Jackson didn’t run the way his former masters thought he would run. Nor, later in life, did he run in the way we might imagine him running. His path provides us with a unique glimpse into how one slave lived out his lifelong imaginary navigation of his surroundings and inner life. It reveals a multi-layered meaning of landscape that Jackson believed he could reclaim before he died, and that we might still reclaim for him today.

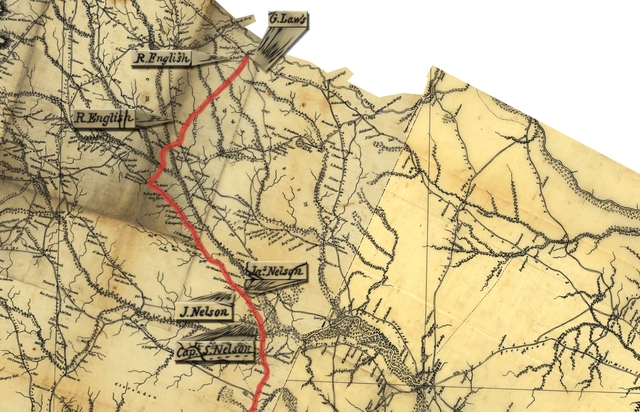

The particulars of Jackson’s storied life are as follows: he was born in Sumter District, South Carolina in about 1825 and was owned by Robert English, a successful landowner with various properties and a host of relatives to share and trade slaves with. The plantation Jackson lived on was in a town once known as English Crossroads, later as Magnolia, and finally as Lynchburg. Despite a brutal life of labor and abuse, he found some brief happiness with Louisa, a young woman he married who lived on a nearby plantation owned by the Law family. His owners objected to his marriage and to his spending time with his wife and Jenny, the daughter Jackson and Louisa conceived. Despite repeated whippings for leaving his plantation to be with Louisa, Jackson remained devoted to his family and determined to keep crossing the land between the English and Law plantations.

In 1846, however, Jenny and Louisa were sold or sent to Houston County, Georgia. Jackson’s devastation knew no bounds, and he resolved to use the rapidly-degrading sanity of Robert English to his advantage. With his owner collapsing into dementia, oversight and discipline of the plantation were lax. Jackson began to hatch a plan for escape. If he couldn’t join Jenny and Louisa, he would escape slavery entirely and perhaps someday, somehow be reunited.

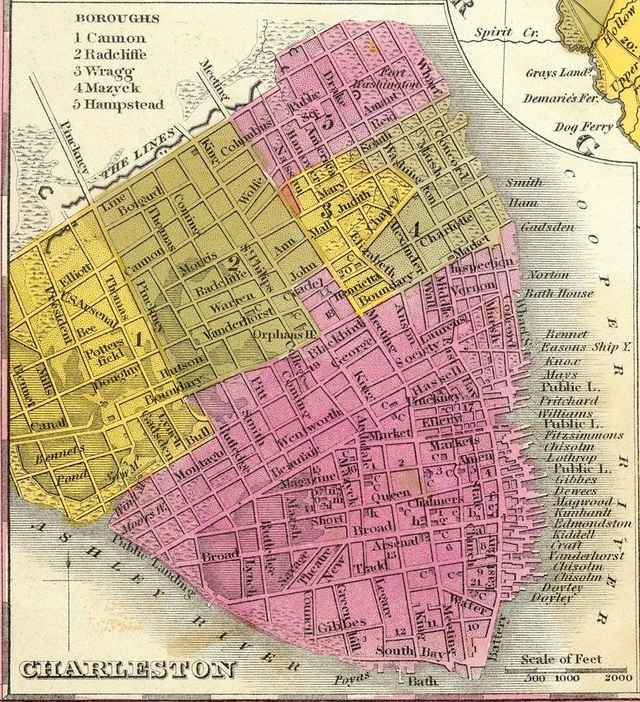

Jackson managed to trade some chickens for a pony that a neighboring slave had somehow obtained. He hid the pony deep in the woods. On Christmas day, he took advantage of the customary three-day holiday and fled on horseback for Charleston. He had often been to Charleston to drive his master’s cattle to market and knew the route well. Unlike many fugitives forced to brave unknown terrain, Jackson’s flight to Charleston was through familiar turf.

It was still dangerous, however, and while he had not worked out the details of what precisely he would do in Charleston, simply and plausibly traveling the over 100 miles of main roads to the city was going to be his greatest challenge. Jackson’s flight over that landscape was thus both typical and atypical of the larger fugitive slave experience.

Fugitives from slavery each had their own horrible story to tell and their own circumstances that led them to seek freedom though “self-theft,” to use the parlance of runaway advertisements in newspapers of the time. But there are some general patterns within the flights of men and women enslaved in the inland South.

To begin with, a vast majority of runaways likely left without any specific plans to abscond north. Rather, they were often fleeing immediate punishment or danger with the intent of returning once the circumstances or threat had changed. A northern escape was a colossal undertaking for people enslaved in the Deep South who had little access to trains or boats. The geographic challenges alone were huge.

Another common motivation for short-term flight, sometimes termed petit marronage, was what took Jackson to visit Louisa; individuals would leave their plantations to see parents or spouses for limited periods of time. This resistance-through-flight was dangerous, of course, for punishments upon return could be murderous. Whether calculated or impulsive, those kinds of flight were still powerful acts of defiance that indicated to overseers or masters that some treatment would not be endured. Despite threats of violence and cruelty, men and women still held some negotiating power: labor was a temporal force, and it meant more at planting or harvest time. If a person could hide for even a week or two, they could deprive their master of labor at an exceptionally critical moment. Punishing that slave too harshly upon their return could be only a pyrrhic victory.

Jackson’s flight this time, though, was the less common form of escape: a grand marronage. He was heading south to Charleston, with plans to then head north for permanent freedom. He had no knowing assistance from anyone, black or white, and he traveled on the roads in plain sight on a pony.

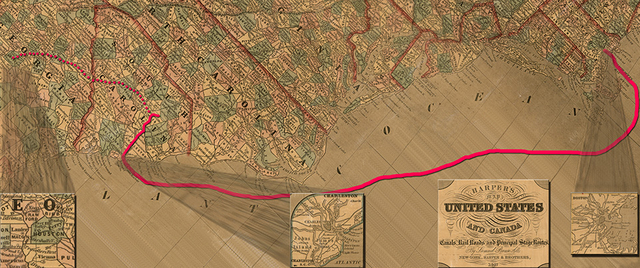

Jackson navigated three kinds of terrain. The first, he imagined and flew over as a bird. The second was the actual historical space of South Carolina and points north that the maps below retrace. Jackson navigated its four essential stages:

Christmas Eve, 1846: Jackson travels through the woods on his pony, stopping at G. Nelson’s plantation: I hastened to the woods and started on my pony. I met many white persons, and was hailed, “You nigger, how far are you going?” To which I would answer, “To the next plantation, mas’re.” But I took good care not to stop at the next plantation. The first night I stopped at G. Nelson’s plantation. I stopped with the negroes, who thought I had go leave during Christmas.

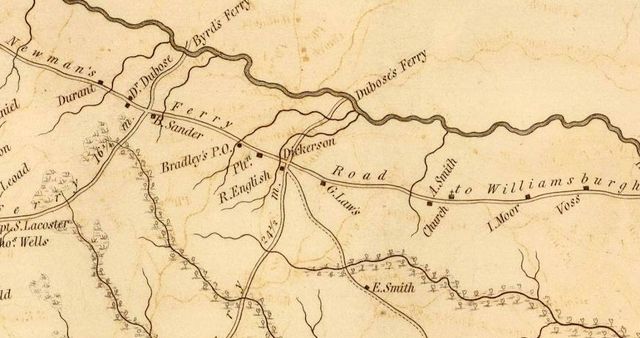

Composite of two USGS Topographic maps digitized by the University of Texas Perry-Castanada Map Library

Christmas Day, 1846: Jackson crosses the Santee River just east of the above stretch, then travels to Shipman’s Hotel, leaving at midnight. Jackson probably crossed the swampy and twisting Santee one unmapped quarter mile to the west of this surveyor’s close up: Next morning, before day, I started on for the Sante [sic] River. The negro who kept that ferry, was allowed to keep for himself all the money he took on Christmas day, and as this was Christmas day, he was only too glad to get my money and ask no questions; so I paid twenty cents, and he put me and my pony across the main gulf of the river, but he would not put me across to the “bob landing;” so that I had to wade on my pony through a place called “Sandy Pond” and “Boat Creek.” The current was so strong there, that I and my pony were nearly washed down the stream; but after hard struggling, we succeeded in getting across. I went eight miles further, to Mr. Shipman’s hotel, where one Jessie Brown, who hired me of my master, had often stopped. I stayed there until midnight , when I got my pony and prepared to start. This roused Mr. Shipman’s suspicions, so he asked me where I belonged to. I was scared, but at length, I said, “Have you not seen me here with Jesse Brown, driving Cattle?” he said, “Yes I know Jesse Brown well. Where are you going?” I answered him, “I am going on my Christmas holiday.” This satisfied him. I was going to take a longer holiday than he thought for.

Jackson reaches Charleston, where he lives for approximately a month: I reached Charleston by the next evening.

Jackson works at the wharfs, and eventually finds a boat to Boston: I joined a gang of negroes working on the wharfs, and received a dollar-and-a-quarter per day, without arousing any suspicion.

But there was a third terrain as well—the terrain he feigned, the verbal map he left to confuse any pursuers.

When questioned by white people he met along the road, for example, Jackson misdirected them:

I met many white persons and was hailed, “You nigger, how far are you going?” To which I would answer, “To the next plantation, mas’re;” but I took good care not to stop at the next plantation.

His landscape was broad, and he was traveling far, but he when he spoke to white people he projected the microcosmic space they expected him to live in: traveling to the next plantation over. He became, at most, a slave running errands. (The population of free people of color in the decades right before the Civil War was small but significant, likely only a few thousand for the entire state. He thus may have also “passed” as an unchallenged freeman on the roads.)

Land and space weren’t his only stage to act upon; he also played with time. When a suspicious innkeeper asked where he was headed, Jackson answered, “I am going on my Christmas holiday.”

“This satisfied him,” he added in his memoir. But “I was going to take a longer holiday than he thought for I reached Charleston next evening.”

Jackson’s greatest feint, however, may be in how he misdirected the Reverend Thomas English, his owner’s son, who managed his father’s plantation and its slaves. When we discovered the advertisement that the Reverend placed in the Sumter Banner in March of 1847, approximately four months after John Andrew Jackson fled, we realized how deeply English was fooled.

Jackson was able to escape in part because Thomas English was looking in the wrong direction. Rather than seek his wife to the west in Georgia, as English believed, Jackson had chosen to head south, to Charleston, a route he knew from previous work leading cattle.

The timing of English’s advertisement also suggests how terrain and speculative marronage were tied. While Jackson’s disappearance was presumably discovered shortly after Christmas of 1846, the first advertisement for him didn’t appear until late March of 1847. This lengthy time lapse suggests that English initially suspected a case of petite marronage, wherein Jackson had merely fled temporarily to avoid a whipping and would soon return. Only after a few months did Thomas English place the advertisement speculating that Jackson had fled over 300 miles to Houston County, Georgia. By then, however, Jackson had already worked for a month on the docks in Charleston before stowing away on a Boston-bound vessel, thus making it North, to freedom.

Reclamation

English misjudged Jackson’s strategy, his temporal plans, and his vision of the terrain. But the slaveholder did get one thing right: Jackson would work for years and at great risk to himself in a futile attempt to free his family.

Jackson’s life after his escape from South Carolina was rich and complex. He labored in Massachusetts for a few years, desperately saving money and networking with abolitionists in order to negotiate the purchase of his wife and baby girl, still enslaved in Georgia. Yet after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, Jackson quickly realized the danger he was in. His master had been making inquiries about him up North, and had commissioned a sort of bounty hunter or agent to track him down. He had to give up on purchasing or ever reuniting with his family. This time, with the assistance of conductors on the Underground Railroad, Jackson made his way north to Canada, where he settled amongst the free black population of St John, New Brunswick.

Jackson married again in Canada and a few years later sailed to England where he lectured for several years about slavery, publishing his memoir The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina in 1862. He chose to return to the United States after the Civil War and spent his remaining years with a third wife in Springfield, Massachusetts. He regularly traveled to and from South Carolina over the next 30 years, seeking to alleviate the plight of the freed men and women there. Jackson collected donations for clothes, farm equipment, money, and food for orphans and the destitute in Lynchburg, the township of his former plantation.

Ending there, however, underemphasizes Jackson’s determination to link land to his freedom. An 1866 newspaper notice in the Springfield Republican reveals the audacious coda that Jackson attempted to give to his life—and to the land where once he was a slave:

John Andrew Jackson, formerly a slave and a fugitive from the South, and lately from Europe, is in this vicinity receiving clothing and supplies to send to the destitute negroes, through the aid society, at No. 76 John Street, New York. He is also trying to raise funds to purchase his old master’s plantation, so that the former slaves may go to work on it, on their own account. He comes plentifully indorsed, and is apparently worthy of assistance in the causes he represents.

[italics ours]

John Andrew Jackson wasn’t merely returning to a region where he had friends and relatives. He was trying to purchase back the very land on which he had picked cotton, the site where his sister had been murdered, the farm where his mother was repeatedly whipped and where he himself had been brutalized. Jackson’s land claim was one born in blood.

As he stated during the escape: “I belong to South Carolina.” It wasn’t an idea he forgot. In an interview of 1893 he told a reporter that he longed to return to South Carolina to die:

… I’m getting old and feeble and I only want to live till I get the money for the Home, and then I will go down to Old Carliny and there is where I want to die, down in my old cabin home.

We can perhaps best understand his intent to reclaim his landscape, the land he had painted with his blood, by looking at the anecdote that closes his entire memoir—the final image to which he, and his readers, must bear witness. In this final passage he tells of a local Sumter slave owner, “Old Billy Dunn” who had whipped a man to death

… and dug a hole in the field, and threw him in without coffin or anything of the kind, just as dogs are buried; and in the course of time, the niggers ploughed up the bones, and said, “Brudder, this the place where Old Billy Dunn buried one of his slaves that was flogged to death.”

I, John Andrew Jackson, once a slave in the United States have seen and heard all this, therefore I publish it.

J. A. Jackson.

The title page and an illustration from Jackson’s memoir, The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina (London, 1862). Documenting the American South, University of North Carolina

Landscape / Escape

So did Jackson actually return to die in South Carolina? It’s hard to say.

He may not have succeeded in buying the exact plantation he had worked, but he did for at least some period own a small parcel of land about six miles from the English family home. As The Watchman and Southron reported in August of 1894, the land of John Andrew Jackson was to be sold for taxes owed.

But had he lived there? His last known location dates to 1896, when the New York Herald Tribune remarked that “John Andrew Jackson lost his satchel in New York City November 18 in Water-st., containing all his clothes; please return to Police Headquarters.” Since Jackson had lost things in previous years and advertised for them in newspapers, this final trace rings true. He may have died there; it’s hard to imagine him returning to South Carolina in his destitute or elderly state.

And yet, for a man who against all expectations had traveled the world, this kind of final and triumphant return still seems believable—especially if we see that return to his primal landscape as the final stage of his escape.

We generally associate ‘landscape’ with ‘escape’ only inasmuch as landscape is something to be crossed or triumphed over in order to achieve escape. Perhaps it hinders or perhaps it assists the escape. The close sounds of the term might also lead us to associate the natural world as itself an “escape” from an unnatural world.

That association, however, is more fraught and complex than instincts suggest. Despite being close cognates, the ‘landscape’ and ‘escape’ have fundamentally distant origins. ‘Landscape’ arises from the Dutch term landschape which suggests a state of being of the land. Initially it was used as a painterly term, the artistic perspective or creation of the land’s very essence or state of being. (‘-Scape’ here functions as a form of ‘-ship’ as it might appear in more familiar terms such as ‘friendship’ or ‘seamanship.’ Only in the last century or so has it taken on the modern sense of it as ‘arrangements of natural forms.’) ‘Escape’ however, comes from Old French: the term eschaper, essentially the removal of a cloak, presumably in order to flee.

The terms share no linguistic lineage, but their overlap is telling. Escape’s origins are revelatory: the unmasking/uncloaking that can allow one to run. Landscape’s painterly origins, which convey a state of being, actually complement the notion of escaping as revelation. Jackson remade the land precisely because he escaped from it. Jackson may never have been able to purchase his master’s land, but he remained invested in it through human bondage, the blood he left behind, the bones he remembered—and flight.

Susanna Ashton is grateful to the University of South Carolina’s Lewis P. Jones Visiting Research Fellowship at the South Caroliniana Library as well as Clemson University’s Cyber Institute which supported this work.