March: Interview with Nate Powell and Andrew Aydin

In June, the Supreme Court struck down the crucial condition of the 1965 Voting Rights Act that required state and local governments with a history of discrimination to receive the Department of Justice’s approval when changing voting rules. Survivors and heirs of the Civil Rights movement decried the decision, worrying that the court had effectively rolled back a generation’s efforts to assure the right of poor and minority Americans to vote.

“What the Supreme Court did was to put a dagger in the heart of the Voting Rights Act of 1965,” Congressman John Lewis, U.S. Representative for Georgia’s 5th congressional district since 1986, told the press. “This act helped liberate not just a people but a nation.”

Lewis would know. Born in 1940, in Alabama, Lewis first aspired to be a preacher, giving sermons as a child to the chickens under his care. At twenty, as a black student at the American Baptist Theological Seminary, Lewis committed himself to the philosophy of nonviolence, which he and other students employed during a series of famed sit-ins to end racial segregation in Nashville’s lunch counters. In 1961 he was one of the first thirteen Freedom Riders, activists who challenged Southern laws enforcing racial segregation on buses. After police-sanctioned beatings by whites and Klansmen in Birmingham, Lewis and Diane Nash, a fellow member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), defied the federal government’s go-slow stance and kept the Riders fighting. In 1963, now chairman of SNCC, Lewis was the youngest member of the “Big Six” leaders of the Civil Rights movement who helped organize the 1963 march on Washington. In 1964, he again put his body on the line, leading a campaign to register black voters in Mississippi. And on March 7, 1965, Lewis and Hosea Williams led the “Bloody Sunday” march over Alabama’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, which ended when Selma police and state troopers rode down, tear-gassed, and beat protestors. His skull fractured, Lewis spoke to the press, demanding President Lyndon B. Johnson’s involvement. Johnson sent the Voting Rights Act to Congress ten days later.

As a Congressional Democrat, John Lewis is as committed to progressivism, justice, and nonviolence as he was in his youth. And in a most unexpected way, he remains in the vanguard. This past August he published the most radical rendition of his road to the Voting Rights Act yet: a comic book.

Titled March, co-written with his press secretary Andrew Aydin, and illustrated by New York Times-bestselling comic book artist Nate Powell, it is the moving first volume in a projected three-volume trilogy covering Lewis’s life in the Civil Rights movement. Elsewhere in this issue we offer a seven page excerpt from March. For this feature, Aydin and Powell took time before San Diego’s Comic-Con to discuss March and its publication by Top Shelf Productions with Appendix editor Christopher Heaney. Interviewed separately, their responses were interwoven for the sake of continuity. Aydin and Powell each shared their thoughts on what it was like to adapt a sitting Congressman’s story to a medium that Congress itself almost eviscerated during its 1954 hearings on the impact of comics on juvenile delinquency.

Aydin and Powell addressed the thorny question of whether history teachers should use Lewis’s graphic memoir as a primary or secondary source. They also debated the necessity of depicting violence in a comic book devoted to working towards nonviolence and love in politics today.

Also revealed? That John Lewis’s involvement in the Civil Rights movement was itself inspired in his youth by a comic book about Martin Luther King. We hope that March might similarly inspire others. As King himself said, “The arc of the Moral Universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” In the wake of 2013’s assault on the Civil Rights Act, The Appendix presents this glimpse into John Lewis’s decision to share his own arc in one of the most bendable mediums of all.

InterviewerJohn Lewis grew up in Alabama, studied in Tennessee, and ended up becoming a Congressman from Georgia. And along the way he read a very influential comic book—one we’ll discuss in a moment. The two of you also grew up reading comics in the South, no?

AydinI’m from Atlanta, born and raised. I grew up in a community where the history of the Civil Rights movement was something we talked about. I think the first time I went to the King Center I was in preschool. My mother was sort of a free spirit. She never stopped me from exploring my own curiosity. I grew up without a dad—he left when I was very young, and I never really knew him—so part of that curiosity went towards finding strong male role models. And if there’s one place that’s dominated by men, it’s comic books. I would read these stories and find some sort of natural relation to them. I think the first time I got a comic was when my grandmother bought me one at a Piggly Wiggly in western North Carolina. Uncanny X-Men, with a lenticular cover.

PowellI was born in 1978. I grew up in a military family for the first ten years of my life, so I lived for a while on a base in Montana and in elementary school I lived in Montgomery, Alabama. When my dad retired we returned to Little Rock, Arkansas, where we lived when I was a baby. My parents and my brother, they all still live there. I’ve been drawing and reading comics since I was three or four years old and have been approaching it very seriously as a creator since I was twelve. It’s one of those things I’ve never looked back from.

InterviewerWhat was your awareness of local history when you were a kid?

PowellGrowing up with my parents, who were Mississippi baby boomers, I definitely was exposed to the 1950s and the 1960s history of the entire south. But really any kid grows up [in Little Rock] being very aware of the Little Rock Nine and Little Rock Central High and what happened there in 1957, and the place it holds in American history.

InterviewerYou’ve shared a story, Nate, about driving past a KKK rally when you were a kid.

PowellBasically it was that in 1983, when I was living in Montgomery, my family and I were I think going up to Anniston, Alabama. And there’s a small town a little bit outside Anniston and we were driving through at lunchtime, and in the middle of the town square there was a fully costumed Klan circle, and they were definitely circled around a giant cross. Now, in my memory the cross was burning but I can’t say with a hundred percent certainty that it was actually burning. The whole experience was so bizarre and uncomfortable to me that I asked my parents, “What’s that?” There was this moment of hesitation where my parents looked at each other before they told my brother and me a little about it. It was my first exposure to racism or the perception of people being of different races or ethnicities as a defining characteristic.

InterviewerHow did March come about?

AydinI was working on Congressman Lewis’s campaign in 2008 as his press secretary, but I was 24 and I was by far the youngest person in the room. There were always these consultants around, and they were teasing me for going to a comic book convention after the campaign was over. That’s not so common or popular in politics.

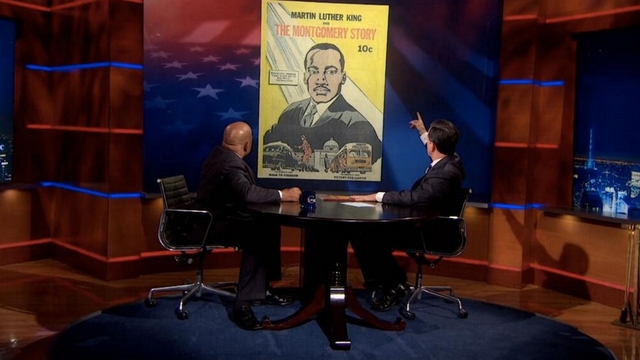

But the congressman stuck up for me and said, “You know there was a comic book during the movement? It was incredibly influential.” And that turned out to be Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story. I went to learn about it, and there was this epiphany moment of, “John Lewis, why don’t you write a comic book?” I asked and I asked and one day he turned around and said “Ok I’ll do it, but only if you write it with me.” It was a put-up or shut-up moment.

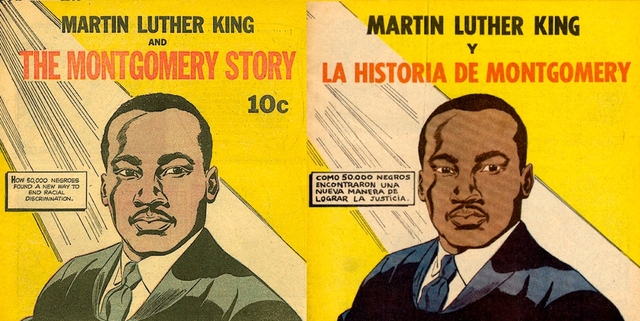

Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, a comic that inspired Congressman Lewis as a young man. It has been translated into Spanish, Arabic, Farsi, and other languages.

InterviewerMartin Luther King and the Montgomery Story is an absolutely fascinating element of this story. It was a comic book published in 1958 by the Fellowship of Reconciliation—or F.O.R., a group committed to the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence—and it dramatized the 1955 bus boycott in Montgomery Alabama for readers. Andrew, you said in another interview that copies of Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story have made it to South America, South Africa, Vietnam, and in 2011, Egypt. How is it that people keep rediscovering this comic?

AydinIt’s usually some geek like me. The art historian Sylvia Rhor has written about how [the Egyptian activist] Dalia Ziada learned about it in about 2006, and [got] it translated. In 1959, when it was banned in South Africa because it was deemed inflammatory, I think it was the Christian missionaries who were getting it through the Fellowship of Reconciliation’s Network. It ended up in Vietnam because of Hassler, the guy who wrote it, who went to Vietnam and became involved in the nonviolent response to the conflict. The Spanish-language version is the one that least is known about. The rumor is that Cesar Chavez used it during the worker’s rights movement in 1968. If that is the case, that would be huge, but it’s never been substantiated in any documented way.

InterviewerYou’ve been researching Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story for a while. How did it get made?

AydinEvery time I turn over a new rock there’s something waiting underneath. I just found a cache of 75 pages of documents from the organization that gave the grant that funded that comic book. You can see the drama of the situation where this was this one hell-bent man, Alfred Hassler, who really wanted to do this, who really thought it could work.

Interestingly, the comic book hearings [in Congress that tried to link the medium to juvenile delinquency] made Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story more possible because it left so many people out of work, who were looking for any gig they could get. Former comic book publishing companies converted into non-profit publishing companies, publishing on-demand academic and educational comic books. The company that produced Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story for the Fellowship was owned by a guy named Eliot Caplan, who was the brother of [the cartoonist] Al Capp [creator of Li’l Abner]. The guy who helped Alfred Hassler write the script was Benton Reznick. But if you look him up in The Ten-Cent Plague, David Hajdu’s book about the comic book hearings, he’s listed in the back as one of those who never worked in the comic book industry again. And yet, here we find that after supposedly being drummed out of the comic book industry he was still making comics, but for a different publisher.

Still, Congress nearly destroyed comic books because they were afraid of their power and ability to influence young people. I think there’s something truly beautiful about someone like John Lewis being a member of Congress and in some ways healing that wound. And in a unique way taking advantage of what they were so afraid of 55 years ago.

InterviewerSo let’s talk about March’s own interesting path to publication. You got help from Karen Berger, the editor of DC’s mature line of comics, Vertigo, in crafting your pitch; and Jimmy Palmiotti at Marvel sent you Chris Staros’s way, at Top Shelf, who then brought Nate Powell aboard. All the while you were writing with Congressman Lewis. What was that like, for this first volume and the volumes to come?

AydinThis is one of those projects where we didn’t have a lot of time to sit down and work on it. We have full-time jobs. Congressman Lewis is the busiest person I’ve ever known. Last night he was voting until 11:30. This morning he was back at 9 for meetings. So our process was finding those small moments, like when we were on an elevator. “I have an idea—you like that? Oh, cool,” and then we were back to work.

When I first started working on the scripts it would be these late nights where I would go home after work and just type. I would have questions and I’d call him and I’d interview him with an earpiece. “OK Congressman, tell me this story,” and he would tell it to me with his own words. I had his memoir of the movement, Walking with the Wind, and a few other major books to serve as guideposts, but I knew a lot of his story already because I’d seen him tell it so many times. I give him the scripts to read at night and he’ll read them and we’ll talk about them. Sometimes here and there he’ll say “You know, I remember this, maybe we could use that?” And so we put together these moments, stories, the way he wants to tell [them], and then I go back and write the scripts to make it a comic book. We’re very collaborative.

PowellWhat’s interesting about John Lewis is that the man is an orator. I wasn’t aware of that until I started. I read his memoir, Walking with the Wind, and at first I thought “some of this stuff is verbatim in the comic. What’s up with that?” But then I realized that this is an entirely different mode of storytelling, [drawing from Lewis’s background as] an orator.

InterviewerSomething that’s going to be interesting for historians is how to use March— whether to teach it as a primary and secondary source, or something in between. There’s the immediate “you are there” experience of Lewis’s radicalization, narrated in his own words, but it’s processed through memory, woven into a script by Andrew, and recreated in Nate’s artwork. Is there a distillation happening? Is that the right way to characterize it?

AydinI think you’re absolutely right. I think we’re all struggling to understand this project because it’s never been done like this. There’s never been a primary figure in history who’s taken the time to work on a graphic novel like this. The closest thing I could ever find was a letter with edits sent by Dr. King to the Fellowship of Reconciliation in 1957 for the Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story comic book.

I can’t think of anything else like it. I mean, Maus, which we love, but here it’s adding a whole other layer and pushing it closer towards primary source material. I think there’s going to be a debate over where that line is. I know we worked really hard to make sure that every detail was as accurate as possible. We’ve been in contact with at least a dozen of the photographers from the movement. You know, folks who were there during the March on Washington, who were there during the early days and the later days. We used an incredible amount of reference photos to make the visuals as accurate as possible. And it’s to the Congressman’s memory of the movement that most people defer.

There’s a joke that Joe Lowery second-guessed the Congressman at one point and C. T. Vivian turned around and said “Don’t second-guess the Congressman, he really remembers.” His memory is vaunted.

PowellWith the case of March, this is John Lewis’s story, but as he admits in Walking in the Wind, it’s not exactly his story: it’s the story of him being a part of a massive social upheaval that needed to happen. So it’s also a challenge of trying to be respectful to the fact that this was a struggle of millions of people, and there were dozens and at times hundreds of people who were doing the same hard work he was doing. While he is the star of this narrative, the challenge is trying not to make him the star all the time. It’s about his role in something that belongs to all of us.

InterviewerI think that comes across in how March starts, with the harrowing Bloody Sunday march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. That flashback ends with Lewis losing consciousness while being beaten by the police, but he’s not even identified at that point; it’s really about all the people who walked across the bridge that day with him and Hosea Williams. The narrative then moves to a really optimistic moment in our present: the 2009 inauguration of President Barack Obama, which becomes the framing device for the rest of the volume. Andrew, how did you and Congressman Lewis decide to link those two moments?

AydinThe framework of starting on Inauguration Day developed after we went through it. I staffed [Congressman Lewis] that day, and it was almost exactly the way it happens in the book. How he wore a big black scarf; our telling him not to wear a hat; him saying things like, ‘There was two feet of snow the day I sat in for the first time.” So we framed it that way because I got to have this unbelievable day at work, witnessing a moment of history from a perspective that nobody else got to see. From the perspective of the guy that Barack Obama singled out to say, ‘This day is because of you.“ It was a great way to tell both of those stories in a totally natural way. “The arc of history is long but it bends towards justice.” You’re not fighting for tomorrow, you’re not fighting for a day, or a week, or a year—you’re fighting for the tomorrows that actually come forty or fifty years from now. And so the inauguration put that in context.

InterviewerWill the next two volumes continue to use the inauguration as a framing device?

AydinThey have themes. The first theme, for the first volume, is New Beginnings: growing up, his first time in the movement, his first time preaching, his first arrest. Just getting up in the morning—the first part of the day. The second volume is about Endurance. And the third book picks up after the ceremony, at the reception, with the president. There are some brutally human moments that I don’t think people knew about from that day, that when they read about will surprise them.

InterviewerSo the third book deals with the achievement of Lewis’s goals?

AydinWe’re focusing on the Civil Rights movement. The congressman will say publically that he saw the Civil Rights movement as being over after the Voting Rights Act [was signed]. But there’s an important epilogue in his personal service and his transition from activist to political operative. When he was kicked out of SNCC in 1966, he spent the next year or two gathering himself and then by 1968 he goes to work for Bobby Kennedy on his campaign. And that in and of itself is an incredible story that I’m looking forward to telling. I don’t think that people realize that the Congressman campaigned with Cesar Chavez on the South Side of LA in 1968, and that he was with Bobby Kennedy on the evening he was assassinated—these moments that were so pivotal to our nation. So right now we’re focusing on ending it in 1968, maybe just a little bit after.

InterviewerThe first volume of March details Lewis’s childhood preaching to chickens, his enrollment in divinity school, and his first forays into non-violent resistance in Nashville. What’s striking is how specific so many of these moments feel—how intimate. That’s partly due to Lewis’s first-person narration throughout, but also because of the art. Nate, what sources do you use to visually reconstruct Lewis’s life and the movement?

PowellBesides spending probably an hour a day looking at [contemporary] cars, technology, shoes, clothes, etc. using Google Image Searches, on a daily basis I reference Walking with the Wind. There’s a book, Freedom Riders, by Raymond Arsenault, and a documentary of the entire bus journey. I just got a book yesterday called Breach of Peace by Eric Etheridge, which features profiles and mug shots of every single freedom rider. And I also have a series of photographic books of the Civil Rights movement. One’s called Powerful Days. One’s called Mine Eyes Have Seen. And then I have a 1960s lifestyle illustration book that has maybe 500 pages worth of fashion design and commercial illustrations from the era to show aesthetic shifts and changes in popular culture at the time.

InterviewerThere’s a prejudice, I think among some, that a comic like this, or a graphic novel, can’t be researched—that it can’t have as great a documentary basis as an article, for example.

PowellYou’re absolutely right. American comics still have this inferiority complex. Every single comics creator—unless they live in a comics bubble, where all their friends are cartoonists—they have to deal with this. There’s this perception that comics are “Books Lite.” Like they’re the Bon Jovi to the Metallica that is literature.

But au contraire! I sometimes take for granted how much more documentation that doing a nonfiction memoir like this, in comic book form, takes. With text there’s a much more concrete application of references and sources. You’re able to lift things and credit them. It’s very clear to see what’s coming from where. But in terms of accuracy and faithful representation, there’s this added weight of the proof being in the visual pudding. So I spend a lot of time either just checking with Congressman Lewis, or even just asking my parents about certain elements of growing up in the 1950s or 60s in Mississippi. If something doesn’t ring true or accurate, it’s pretty immediately apparent when you’re using visual art to represent a certain time and place.

InterviewerThe department stores that Lewis and his fellow students sat in, for example—were you able to research what they specifically looked like, their layout?

PowellWell, I tried hard. In Book One I was actually able to find images of the exterior of the actual stores and in some cases find shots of the specific lunch counters. But for the most part, with the exception of these incidents—the sit-ins, the beatings—not a lot of people are going to be taking photographs of the inside of the department stores and still have those photos. So I certainly had to do enough research to be able to make a composite of what a Ward’s counter would look like. I was able to go to Alabama in March and go on the Faith & Politics Institute Pilgrimage to Civil Rights spots with the Congressman and some other folks. So I was able to finally get inside some of these churches, go to some of these basements, go inside MLK’s office in Montgomery and witness the space firsthand.

InterviewerDid you ever catch yourself thinking “Oh, maybe I didn’t get it quite as right as I wanted”?

PowellOh, all the time. With a book like this there’s this line between accuracy and leaving enough room for gesture and iconographic representation to breathe life into something without it being dry. I feel like there’s a point where I have to stop trying to nail everything one hundred percent because you’re going to wind up with a boring history comic that looks dry because you’re so concerned about sticking it in a certain place and time.

InterviewerThere are two things that I find very powerful about your artistic style, Nate, both here and in an earlier memoir-type graphic novel about the Civil Rights movement that you illustrated, The Silence of Our Friends. The first is your ability to depict scenes that would be pretty leaden in other comic book artists’ hands, like talking or riding bikes, and filling them with foreboding or joy. It reminds me of good Japanese manga comics, which use angles and impressionistic expressions, not exact realism, to convey emotion.

PowellAs I was working through the script for Silence of Our Friends, that’s where I first developed an understanding for my role as the visual end of the storyteller. In absorbing all the information in the finished script, I had to learn how to also depict what was not included: tension, dread, the passage of time, and the way silence actually works. I think my greatest influence, [in terms of] the way my narrative flows, is Katsuhiro Otomo’s storytelling style, specifically in a book called Domu: A Child’s Dream, which I think he did right before he started Akira. Thank you for noticing that!

InterviewerThe second thing I find so powerful in your work—and it’s particularly striking to anyone who has thought about the mark that superhero comics have left on the form—is how you depict violence. Comic books in general have a very violent past, and superhero comics, for all their fun, also often romanticize violence. That’s clearly inappropriate for books on the Civil Rights movement, and you handle that in a really interesting way.

PowellYes, I think for March and Silence of Our Friends both—because they do contain so much brutality within them—one of the challenges was in depicting the violence within someone else’s story without romance and sentiment—the way we’re used to seeing violence depicted in comics. And by violence I also want to include the use of racist language. You want to make sure that you’re representing something as it occurred, and that by remaining as close as possible to a depiction of actual events you can take the sheen off the violence and the language, letting you see it in a more brutal light than you would in any other way.

InterviewerWhich leads us to what might be March’s most brutal image: the body of Emmett Till, whose murder in Mississippi in 1955 left a deep, awful impression on Lewis, who was fifteen at the time, and the African-American community.

PowellYes.

InterviewerOutside of Lewis’s memory of the news, you depict both Till’s funeral, as well as his body being pulled from the water. Did you grapple with how directly to draw those moments?

PowellCertainly. I think that those two panels with Emmett Till are the most potent examples of the issues of representation and authorship in the book. When I did that page, I was finished with [it] by eleven in the morning but I was done drawing for the day because [it] was so intense. Now, in the original script, the captions and text describe what happened when allegedly he said “Bye, baby,” to that white girl, but the representation of Emmett Till[‘s body after being pulled from the water] was not as explicitly described in the script as I made it. To make sure I had it right, I had to see pictures of it … There was a shot that was more explicit of his mother crying at his casket—and there’s a photo of this as well. Originally I drew that panel with his mother at his funeral, but it was really direct—as direct as the photo—and I actually felt it was a little bit cheap. That had to do less with the representation of Emmett Till’s body as it did with the representation of his mother in anguish. I felt that wasn’t appropriate. So I pulled the camera back and made it a silhouette shot because… we get it.

But with the depiction of Till’s body actually being pulled from the river … this goes back to these questions of making violence plain and thus making it truly shocking and brutal again. With that panel I thought that my responsibility was in a very plain way to draw his body with the fan unit and the rope and the chains as accurately as I could from his funeral and his autopsy without being excessively graphic—but in a way that showed the bloating, the disfigurement that occurred as a result of the violence committed upon him. To basically allow the image to do its own shocking of the reader. The violence is also big in in Book 2, because people get destroyed during the Freedom Rides. There are times where I’m drawing people getting crates smashed over their heads and dragged under cars, and a white parent holding an unconscious man between his knees while encouraging his kids to claw his face up and claw his eyes out. There are times where I actually catch myself [thinking] “Is this necessary? This is a little much.”

But you have to remember that this is not a Frank Miller script, this is what actually happened to real people and Lewis, the person who wrote this, saw it happen. And it changes the representation of violence completely. It allows you to approach it in a way that it does its own shocking simply by depicting the image itself. You don’t have to do much else than that.

InterviewerThe panel after Till gets pulled from the water depicts one of the white defendants acquitted of the murder, being congratulated by his lawyer. The contrast is quite upsetting.

PowellWhat’s crazy is that in one of our final edits we actually added a line of text to the end of that panel because I did a little follow-up and I was able to verify that the very next year after they were acquitted, I think it was like five months later, one of the murderers admitted on TV that they killed Emmett Till. None of them ever faced any charges. One of the dudes is still alive and lives in Glasgow, Kentucky. He may have died of cancer in the last couple of years. But these dudes were alive and kicking, living their normal lives, having confessed on TV to murdering a man but due to double jeopardy were able to get away with it. To me that panel is as horrifying as Emmet Till’s panel.

InterviewerSince you finished March, the story it documents has gone from history to current events one again. We’re talking shortly after the Supreme Court made the decision that, as Congressman Lewis said, “put a dagger in the heart of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.” Meanwhile, the two of you have participated in panels on graphic arts and social change. What do you think March says, moving forward, that you might not have thought it did when you started it?

AydinWe couldn’t have foreseen this five years ago when we started this. But the Congressman has this saying that sometimes you’re being swept up in the spirit of history—the spirit of history is pushing you in a certain direction. There are plenty of moments in his life where something didn’t work out for him but in the end it was this unbelievable thing that opened so many other doors and experiences. Maybe this is premature, but I think maybe we’re seeing something like that. Something that’s bigger than him or I or any of us. Because it’s time for the next generation to step up.

PowellWhen I started the scenes on Emmett Till through Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott, I realized that while as a Southerner growing up in the 80s, I was very aware of who Rosa Parks was by the time I was seven, and what she meant for the rest of the South and America, 20-year-olds in 2013 may well not know who she was and what she did, or Malcolm X, for that matter, or even Dr. Martin Luther King. And as our baby boomers get older, and our first-person exposure to the Civil Rights story begins to thin, it becomes even more imperative to create a breathing document of that time.

The fact that just a week ago today was the gutting of the Voting Rights Act—which was a direct result of John Lewis and the his friends and other activists getting supremely beat down by the state troopers and white supremacists in Selma in 1965—is so unfortunate. It’s shocking and mind-blowing that this is now a news item instead of being something you need to write about that happened fifty years ago. But it’s a wakeup call. All of a sudden you’re moving closer to 1964 than you were a couple months prior.

InterviewerAndrew, you’ve called Congressman Lewis a “Radical for Love.” What does that mean, to you?

AydinI think John Lewis is a man who has had unbelievable wrongs done to him. And yet he never became bitter. He never became hostile. And in fact he learned through his devotion to the philosophy and discipline of nonviolence to love the people who were doing the wrong to him. And I think about that in my own life and how people who make me mad—Lord knows I get mad enough at the cable company—but these people were beating him, these people were trying to kill him, and yet he still found it in his heart to love them, and believe they could make a contribution to our society. You know, after Barack Obama was inaugurated, a guy from Rock Hill, South Carolina came to the office and apologized for beating Congressman Lewis in 1961. And it was a powerful moment not just because of what the inauguration meant to people, but what it meant for John Lewis to be able to forgive him.

PowellI want to add that Congressman Lewis is the genuine article and so obviously this is his story and so from a professional perspective and an ethics perspective from his side, I defer to him. Getting to read about him just having this incredible vision from a young age, just seeing past so many social constructs we establish as human beings to each other, his ability to be truly dedicated to kindness, to forgiveness, to real progress—it makes you feel like a dumbass in the best possible way. Hearing these tales of former Klansman or former police officers reaching out to him for forgiveness, admitting that they put him in the hospital once, and his ready acceptance of that apology, his ability to forgive, an ability to see the big picture—you know this is the kind of thing people want to treat as a cliché, they want to treat the spirit of forgiveness as a weakness. But getting to see somebody who really has lived it and breathed it and continues to fight the good fight—it’s something that becomes more vital to me every day, just the fact that he’s willing to put the effort forward to forgive people who have committed such unspeakable acts against him.

AydinWhen I say that John Lewis is a Radical for Love, I mean that I think our society has become so focused on getting even, on conflict almost as a lifestyle. I mean that his ability, his capacity to love everyone, people who have done him right, people who have done him wrong, is something we all need to learn how to do. This is a man who can exist in the United States Congress and bring to something as abstract as policy a point of view that preaches loving each and every one of us. When you think of that as a policy perspective… We’re so worried about dollars and cents, and bombing a country and staying safe, that we’ve completely forgotten what it’s like to love the fact that we’re American, to love other Americans. We’re too afraid to love people. We’re too afraid to feel love. And that’s his message. Don’t be afraid to love people. Don’t be afraid to love everyone, because it will change your point of view. And it will make your life better. And it will make everyone else’s life better too.

I guess that’s what I mean.