Bandit Resurrections: Who Was the Real Sundance Kid?

Last summer, Wyoming Governor Matt Mead received an odd present from an Arizona businessman named Jerry Nickle: a just-published book promoting the idea that the author’s great-grandfather William Henry Long was none other than the Sundance Kid, of Butch and Sundance fame. Even more surprising than the book was its delivery. Nickle and his co-author had borrowed horses in Cheyenne and rode along the sidewalk to see the governor.

Not only does Nickle claim that his great-grandfather Long was the famous Wild Bunch bandit—he also maintains that he and Butch Cassidy were not killed in Bolivia, as many believe. Nickle believes that his great-grandfather did not commit suicide, as his family long thought, but was murdered by fellow Wild Bunch member Matt Warner after an argument about a book Warner had planned to write that might have exposed Long as Sundance. Nickle’s enthusiasm is not dampened by the absence of any evidence linking his great-grandfather to the Wild Bunch, or any evidence that he had ever even claimed to be the famous outlaw. After DNA tests failed to establish a link between Long and the Sundance Kid’s actual family, Nickle turned to a new theory: his great-grandfather had stolen the identity of Harry Longabaugh, the man Western historians actually consider to be the Sundance Kid.

Welcome to the kaleidoscopic universe of Wild West history, where outlaws return from the dead with vampiric regularity. Long is by no means an anomaly, as bandit revivals are relatively common—at least among the better known of the criminal class. While in some cases a dead outlaw’s identity is attributed to another deceased person—often by his ancestor—in others it is assumed by a living person, an imposter. These resurrectionists are a mixed posse of pranksters, genealogy boffins, and conspiracy theorists who cannot accept that their bandit hero is dead. And they find a ready audience because, well, who can resist a good story from the campfire?

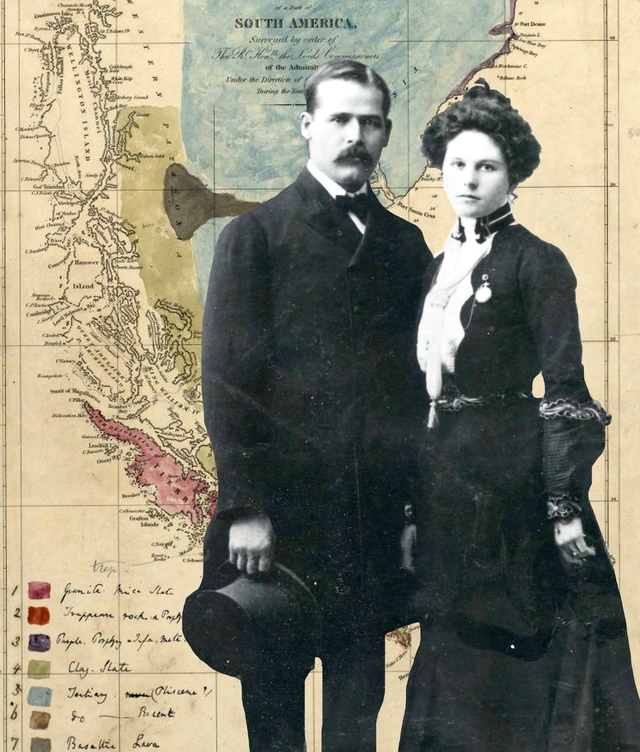

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were part of a loose-knit congeries of Rocky Mountain outlaws active at the turn of the last century, dubbed “the Wild Bunch” by the press. Although Butch and Sundance committed few crimes together in the United States, they are indelibly joined as an outlaw dyad in the public’s imagination because they fled to South America together (Sundance took along his companion, Ethel Place), probably died together in Bolivia in 1908, and, most importantly, were immortalized together in George Roy Hill’s 1969 movie, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Making a major contribution to the deification were Paul Newman as Cassidy and Robert Redford as Sundance.

Claiming to be Butch and/or Sundance (or any one of the many other famed bandits of the Wild West) has a long and storied tradition. William Henry Long, for example, is not the first man to have been volunteered as the Sundance Kid. In 1983, Connecticut high school principal Edward M. Kirby published The Rise and Fall of the Sundance Kid, which argued that criminal Hiram BeBee was Butch Cassidy’s sidekick. BeBee died in a Utah prison in 1955 while serving a life sentence for the 1945 first-degree murder of a town marshal. As with Long, there was no evidence that BeBee had any connection to the Sundance Kid, save what Kirby said were unspecified alleged remarks of BeBee’s that were never made public.

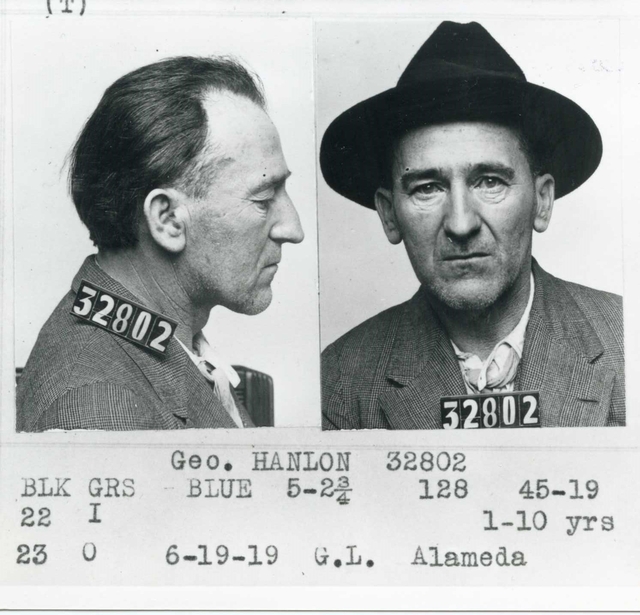

These hinted, covert identities are often absurd when laid against the reality. Aside from the lack of any link between BeBee and Sundance, there was a major physical disparity. BeBee was ugly and short, not quite five-foot-three, per a 1919 mug-shot card at San Quentin, where he had done time for rolling a drunk. Sundance was handsome and tall, upwards of six feet. BeBee looked like Jimmy Durante; Sundance indeed looked more like Robert Redford, his silver screen alter ego.

1919 San Quentin mugshot of Hiram BeBee, aka George Hanlon, sentenced to 1 to 10 years for rolling a drunk. California State Archives

Sundance was not the only Wild Bunch member to have his identity stolen by a revivalist. In the 1920s, years after Butch Cassidy had expired in Bolivia, a Washington state machine-shop owner named William T. Phillips began visiting the outlaw’s Wyoming haunts, searching for bandit treasure and dropping hints that he, Phillips, was the real deal. Some of Cassidy’s old friends were taken in, others scoffed at the idea. Phillips wrote a memoir, “The Bandit Invincible,” which he hoped to sell to Hollywood. The memoir was a hodge-podge of fact and fantasy, written more like a novella and told almost entirely in the third person, as if Phillips would barely allow himself to hint at his supposed identity as Cassidy.

Yet Phillips’s con had legs. He died in 1937. More than three decades later, Larry Pointer, then a Bureau of Land Management staffer in Wyoming, came upon the tale, and after considerable additional research, persuaded the University of Oklahoma Press to publish In Search of Butch Cassidy, a sort of dual, or better put dueling, biography of Cassidy qua Phillips.

The story was intriguing, because Cassidy vanished in 1908, presumably killed in Bolivia, and Phillips appeared on the scene in the United States in 1908, as if out of nowhere. But the larger possibility that Phillips was Cassidy couldn’t pan out. In the late 1980s, when Anne Meadows and I began researching the story of Cassidy and Sundance in South America, we found that although Phillips had claimed that he had escaped the shootout in Bolivia and returned to the United States, getting married in Michigan in May 1908, the shootout had in fact happened in November, after his marriage.

The calendar is the researcher’s best friend. As are maps: Phillips had located the bandits’ Argentine ranch in the wrong part of Patagonia, had them holding up trains that were not yet built at the time they were in South America, and had them bivouacing for several days in a village in northern Argentina, Gaciayo, that turned out not to exist. Gaciayo is a fake cartographic entry, also known as a Mountweazel, designed to catch copyright violators—competitors who poach maps. Phillips had been no closer to South America than the atlases he carelessly consulted.

Pointer wiggled around the marriage date problem by positing the idea that there were several Cassidys, before finally throwing in the towel when it turned out that Phillips was actually William T. Wilcox, a petty criminal who had been in prison with Cassidy in the 1890s.

Bandit resurrectionists eschew Occam’s Razor. When faced with an inconvenient fact, they roll out a deus ex machina—one after another if necessary—until all contradictions are enveloped in an elaborate web of preposterous explanations.

“Brushy Bill” Roberts surfaced with his own bundle of contradictions in New Mexico in 1950, claiming to be Billy the Kid. He was chaperoned by a lawyer and wanted a pardon, though for what was not clear, as his crimes were seven decades old. The actual Billy had been shot dead in 1881 by Sheriff Pat Garrett.

Roberts talked a good game—previously he had claimed to be Jesse James—and he garnered more than a few supporters, including his hometown, Hico, Texas, which opened a “Billy the Kid Museum and Gift Shop.” He had lots of press over the years. Reporters relish back-from-the-dead outlaw stories; they’re fun to write and the readers lap them up. In modern lingo, they’re clickbait.

Serious Billy the Kid historians do not give Roberts’s tale any credence. The Roberts family’s Bible reportedly lists his birth year as 1879, making him two years old when Billy was shot. He was an actual kid, but not Billy.

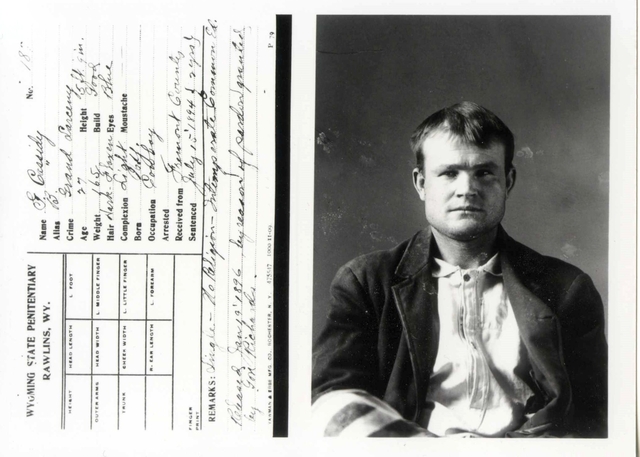

Wyoming State Penitentiary mugshot of Robert LeRoy Parker, AKA Butch Cassidy, 1894. Wyoming State Archives

Before Roberts came along, there was John Miller, who died in Arizona in 1937, more than half-a-century before his resurrection went public, stoked by Helen Airy’s 1993 book, Whatever Happened to Billy the Kid. According to Airy, whatever happened was that Miller was the revered bad boy. Evidence in support of Miller’s having been Billy included private comments he had reportedly made to that effect and the fact that he had buck teeth, as did Billy. (As did Bugs Bunny, come to think of it.)

Jesse James, however, was the true magnet for bandit resurrections. No matter that in 1882 the outlaw had been murdered in his own house, and that his wife and mother had buried him. Half a dozen men later either claimed to be the Missouri bandit or were shoved forward by their descendants.

J. Frank Dalton is the most well-known of the pack. His story was broadcast by an Oklahoma radio station in the late 1940s, and the next day, the Lawton Constitution headlined, “Jesse James is Alive in Lawton.” At Dalton’s first public appearance in town, some 30,000 people came out to gawk. He went on to a brief career—he died in 1951—making personal appearances and working the carnival circuit, ending up at Meramec Caverns in Missouri, sharing the stage on one occasion with Billy the Kid hoaxer Brushy Bill Roberts.

Decades after the J. Frank Dalton controversy had faded away, Betty Dorsett Duke stepped up to announce that her great-grandfather, James Lafayette Courtney, was Jesse James, having escaped death in 1882 when another man was killed instead, and lived until 1943. Duke wrote, as seems to be obligatory, a book, The Truth About Jesse James, As Told by His Great-Granddaughter (2007). Over the course of 672 pages—almost 200 pages longer than the outlaw’s definitive biography, Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War (2002), by T.J. Stiles—she pelts the reader with arguments, among them that her great-grandfather hid gold coins around his property, and whenever anyone approached his farm house at night, he would douse the lights and lurk by the front door with a loaded pistol.

Among the inconvenient contradictions Duke skirts: Jesse James was of average height, 5’ 7” or so, and Courtney was well over six feet. More importantly, Jesse James’s wife was in the next room when he was murdered in 1882, and she buried him. Duke couldn’t even win over her own family. Angry Courtney descendants launched a competing website to refute her claims.

It does not seem to matter if an outlaw dies a disputed and anonymous death, as in the case of Butch and Sundance, or in full view of his family, as with Jesse James. Doubts will linger, and sooner or later, pretenders appear. “To some extent,” English historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote in Bandits (2000), the resurrection of the bandit:

expresses the wish that the people’s champion cannot be defeated, the same sort of wish that produces the perennial myths of the good king—and the good bandit—who has not really died, but will come back one day to restore justice. Refusal to believe in the robber’s death is a certain criterion of his ‘nobility’ … For the bandit’s defeat and death is the defeat of his people; and what is worse, of hope. Men can live without justice, and generally, must, but they cannot live without hope.

Hobsbawm might be overthinking it. It’s just as likely that bandit revenants spring as much from yarning and pranking, American folkloric traditions that have given us Bigfoot and the jackalope, and from the longstanding attraction of conspiracy theories and genealogy.

North Carolina State University professor Richard W. Slatta examines the storytelling tradition in The Mythical West: An Encyclopedia of Legend, Lore, and Popular Culture (2001). “Myth is more powerful, pervasive, and alluring than history,” Slatta writes. Accordingly, he focuses “on the plethora of legendary, mythical images, events, people, and places associated with the Old West and New.” Pranking is likewise popular in the United States. Many urban legends start as a joke. Once launched, the joke billows into legend. The son of original Bigfoot proponent Ray Wallace, a northern California construction worker, told the press after his father died in 2002 that the whole thing had been an elaborate stunt, involving among other things, huge wooden feet used to create the forest giant’s tracks. Nonetheless, the hunt for Bigfoot continues unabated.

Two of Butch Cassidy’s brothers reportedly impersonated him for sport. One of his doppelgangers, William T. Phillips, took periodic leave of an unhappy marriage in Spokane to visit the outlaw’s haunts in Wyoming and take up with a girlfriend. She confided after his death that the Cassidy burlesque was all a joke.

Conspiracy theories often underpin outlaw resurrection stories. J. Frank Dalton claimed that he—the real Jesse James—hid in a stable near his house while someone else was shot in his stead. Brushy Bill Roberts said that with Pat Garrett’s connivance another man was killed in his place, allowing him—the real Billy—to escape to Mexico. Explanations for Butch and Sundance having survived the shootout in Bolivia range from changing clothes with dead soldiers to an outright refusal to believe that Bolivians could do what Americans could not, bring down two of the Old West’s most well-known outlaws. In fact, most of the Wild Bunch members were captured or killed by American lawmen, and for their part, Bolivian soldiers and mine-camp posses caught most of the bandits operating in their country in the early 1900s. Banditry is an unforgiving occupation that provides little room for error.

The faked death phenomenon encompasses many historical figures, not just outlaws. Examples include Martin Bormann, Adolf Hitler, T.E. Lawrence, Pancho Villa, and Tupac Shakur. “One hesitates to believe [the Bormann] story,” Christopher Isherwood wrote, “if only because it is a variant of the basic immortality legend which is often attached as a postscript to the apparent death of great or notorious men.” A friend in Bariloche, Argentina, once showed me a map of the town cemetery indicating precisely where Hitler was buried. He asked me not to tell anyone. I haven’t, until now.

Interest in genealogy, fueled by popular websites like Ancestry.com, has also played a role. James Lafayette Courtney and William Henry Long were both “discovered” by descendants poking around in their ancestral attics. The lack of any evidence linking the men to Jesse James or the Sundance Kid was a minor inconvenience. A staffer at the National Archives, which fields many genealogical queries, told me that people always want to find a famous person roosting in their family tree. The don’t much care who it is, Joan of Arc or Jack the Ripper, just so long as they get bragging rights.

No excursion into the world of bandit revivals would be complete without mentioning Robin Hood, the fountainhead of bandit mythology. The idea of the good bandit, who robs the rich and gives to the poor, who saves the widow’s farm, and whose death is unacceptable comes from Robin Hood, writes Stephen Knight in his Robin Hood: A Mythic Biography (2003). “The only modern film that has shown the hero’s death,” says Knight, “Robin and Marian (1976), is the only one to have lost money at the box office.”