Meerkats Without History: Digging for a Non-Human Past in the Kalahari Desert

The truth is, that man is a creature of greater power than other living creatures are … There be beasts that see better, others that hear better, and others that exceed mankind in all other sense. Man excelleth beasts only in making of rules.

— Thomas Hobbes, The Questions Concerning Liberty, Necessity, and Chance (London, 1656)

In my senior year of college, I became mildly obsessed with the television show Meerkat Manor. The program billed itself as lighthearted reality TV about a cuddly gang of meerkats trying to get along and find grubs in the harsh environment of the Kalahari Desert. It was the Real World meets Survivor—only with humans replaced by tiny mongoose-like creatures known mainly for their adorable posture.

The actual footage and research undergirding the show was surprisingly highbrow. A note at the end of each episode explained that the meerkat group documented in the show was being studied by a University of Cambridge zoological team. These human giants were forever off camera, except for occasional moments when a wayward meerkat happened upon their encampment. In one such encounter, the absurdly small scale of the meerkat was revealed as it stood looking up in mute incomprehension, dwarfed by the leather boots of a bemused English scientist.

The crew of Meerkat Manor: the Story Begins observing their subjects in the Kalahari. Mike Slee

Luckily (for American audiences, at least) any threat of didactic content was negated by the fact that the narration came from the guy who plays Sam in The Lord of the Rings. For the most part, old Sam stuck to cliffhanger updates like, “The sun is setting, and the danger seems to have passed,” or offered a folksy running commentary on the despotic whims of Flower, the tribe’s supreme leader.

I was initially sucked in by the escapist soap opera element of the show, which gave every ‘kat a distinctive name (Mozart, Shakespeare, Rocket Dog) and carefully explained their lineages. Almost every meerkat in the group, it turned out, was a direct descendant of Flower, a five-year-old alpha female whose toughness, fecundity, and grim survival skills were unequaled in the rugged stretch of Kalahari that these meerkats called home. My favorite was Flower’s former mate, Yossarion, who the opening credits warned us had “some social problems.” A sinister, Richard III-like figure, Yossarion bore a scar above his left eye that testified to his rare survival of an eagle attack. He’d been dropped on his head from a significant height, and retained a twitchy, crazed unpredictability that made him the show’s obvious villain.

My friends all thought my love for the show was an expression of my soft side, akin to watching videos of sleeping kittens. And it’s certainly true that meerkats are cute. They enjoy group cuddling in their burrow after the workday has drawn to a close, and sometimes they become so overwhelmed by their rapid metabolism that they simply collapse and start napping. They do that cute standing on their hind legs thing for which they’ve won international renown. They even engage in complex social behaviors like wrestling matches and clan warfare, and they teach their young learned techniques like how to remove stingers from scorpions. They’re neat animals.

The alpha female meerkat of the Whiskers clan, Flower, guarding her grandchildren. Wikimedia Commons

In truth, though, I was drawn to the darkness of meerkat life. Beneath the kid-friendly surface, a Shakespearan drama was unfurling in those South African burrows. It was like watching King Lear or Titus Andronicus acted out by suricates with brains the size of walnuts. When a close friend gave me a sidelong glance after watching an episode and said, “You know what? You’re kinda like a meerkat,” I took it as a strange sort of compliment, but I had to think about it first.

A typical meerkat inhabits a world of revenge, suffering, and endless toil. The cuddly characters of the show were regularly stung by poisonous asps, lifted off camera in the talons of enormous raptors, or (most common of all) expelled from the group like Old Testament exiles, lost to wander in the desert until they expired from thirst. Even the ‘successful’ meerkats, the ones permitted by the matriarch to have children and live with the group, had lives that resembled Victorian factory workers, spending almost all of their waking hours on the tedious dual tasks of lookout duty and grub-hunting. Watching successive generations of meerkittens enter the world in their cozy dugout burrows, play with their siblings for a few days and then get roped into this life of endless labor began to feel less like an excuse to avoid writing my term paper, and more like an exercise in masochism.

Eventually I stopped watching. It was too much. But the show stuck with me as I entered grad school and became an historian, reading works like E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class (1963) and anthropologist Eric Wolf’s The People Without History (1982) that argued for an expansion of the groups surveyed by the historian’s gaze. The past was not the sole domain of elite government actors: it was instead collectively made by countless ordinary people who occupied the edges of traditional historical narrative.

On the occasion of our fifth issue, “Digs,” I began wondering whether the circle could be expanded further. Complex mammal societies like those of primates, dolphins and even the humble meerkat must give us pause when we think about the past. The intergenerational dramas of the Kalahari’s tiny diggers implicitly pose a question I’ve been kicking around for years, and don’t yet have a good answer to. Do animal societies have histories? And if so—does that make history a hell of a lot darker?

Thomas Hobbes helped set the division between human history and natural history on its current course by investigating what he called “the state of nature.” The philosopher held a dim view of humanity. “Man to Man is an errant Wolfe,” he epigraphed one of his books, and in Leviathan he wrote that the “natural condition of mankind” was essentially one of constant warfare, “wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish.” Such a life, Hobbes famously concluded, was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.”

Hobbes could just as easily be talking about meerkats. When Yosarrion, the villain of Meerkat Manor, is finally expelled from Flower’s brood and forced to wander in the desert in search of a mate, he is stripped of his role in meerkat society. Meerkats organize themselves into complex social groupings, with assigned tasks (finding food, guarding infants, and standing on tall objects looking for eagles) that shift on a daily basis. On their own, meerkats quickly succumb to predation. Only by forming what Hobbes called the “Leviathan” of a “civil society,” a well-ordered group with a leader and internal rules, can meerkat bands effectively survive.

Yet any Enlightenment philosopher—indeed, any early modern European person—would’ve scoffed at my line of argument here. “Animals aren’t the slightest bit like us,” I can imagine this seventeenth-century straw man saying. “We were created by an Almighty God in His divine image; God made the beasts to serve us. They may be sentient creatures, but they are not Rational.” Hobbes was an iconoclast, and he didn’t hew to the Old Testament party line in this regard. Yet he still believed that humans were naturally superior to all other creatures because of our

use of speech, by which men … join their forces together, and by which also they register their thoughts that they perish not, but be reserved, and afterwards joined with other thoughts, to produce general rules for the direction of their actions.

In short, the key—indeed the only—human gift is our ability to remember, and to organize and learn from our collective memories. Which, of course, is simply another way of saying “history.”

When I was a kid, I loved Richard Adams’ classic adventure novel Watership Down.

Adams modeled his narrative on Virgil’s Aeneid, inventing a complex society of anthropomorphized rabbits whose idyllic South English burrow is destroyed by construction work. A handful of dazed survivors manage to escape, traveling the countryside in search of a new homeland. The core of the story is Adams’s marvelous ability to evoke the mental life of a rabbit (the main characters are terrified by just about everything that doesn’t involve leafy greens) while imbuing them with human emotions, thoughts, and even nobility. It’s a masterpiece of the animals-as-humans genre that has yet to be equaled, as far as I can tell.

When we narrate animal lives—both in fiction like Watership Down or the Redwall books or Finding Nemo, or in documentaries like March of the Penguins—we can’t resist the urge to invest them with our own emotions. I’m no less guilty of this than anyone else who writes about animals.

But what happens when we treat animals as actual animals? Can we write historical narratives about non-humans that avoid anthropomorphized emotions, yet treat them respectfully as thinking, sentient beings who share with us a fundamental subjectivity, a sense of themselves as themselves? And if so, what in the world would such a narrative look like?

Meerkat Manor fascinates me still, because it lays bare the strangeness of how we narrate animal pasts. The show was framed with kooky music, a comforting narrative voice, and a cute name (a more accurate one would be Meerkat Hole in the Ground or Meerkat Endless Terrifying Desert Filled with Scorpions, but those don’t have quite the same ring).

In truth, though, the lasting value of Meerkat Manor is that it was surprisingly blunt about the brutal lives of its subjects.

I’ll never forget the moment when Shakespeare, one of Flower’s strongest children, is bitten by a puff adder, causing his leg to swell and become immobile. He’s a goner. But, miraculously, Shakespeare’s sister finds him twitching in the sand, and drags him back to the burrow they share. She even appears to tend to him, licking his wound and bringing him herbs to nibble on. Shakespeare survives. It’s a remarkable moment, and I was genuinely moved by it. But for every story like that, Meerkat Manor brought us darker ones, like when Yossarion, in a moment of derangement, drags his infants out from their burrows and leaves them to die in the sand for reasons unknown to the show’s producers, and maybe to Yossarion as well.

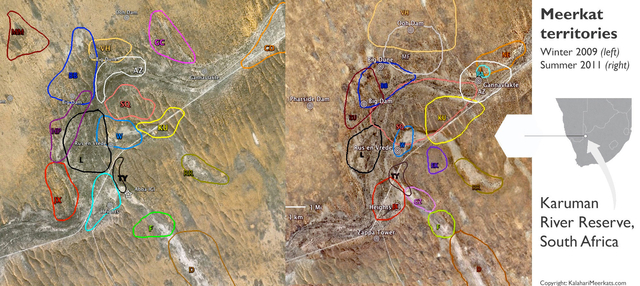

A composite map of meerkat clan territories in 2009 and 2011. Is there a parallel with human societies? Kalahari-Meerkats.com

The uneasy distance between the stark realism at the show’s core and the cute animal trappings that disguised it was widened by the death of the matriarch Flower in 2006. Fatally wounded by a snake, Flower succumbed to venom before the camera’s unblinking eye. Viewers were outraged, questioning whether it was ethical for the producers to stand by and watch her death rather than administer anti-venom. The producers rejoined that the goal of the Cambridge meerkat project was to study “the breeding success and survival of individuals and … the factors that affect reproduction and survival.” Intervening in the natural order of things wasn’t in their ambit. Indeed, it would be an injustice to the empirical methods and goals that underlay the project: if researchers intervened in meerkat lives, their own scientific efforts would be invalidated.

The show Meerkat Manor was only an illusory epiphenomenon, an excrescence of cuteness, atop the workings of the Cambridge zoology group that was actually monitoring the individuals involved. And Animal Planet viewers can’t mess with Science.

Meerkats are not people, events like this tell us, no matter how many human names we give them. It’s fun to imagine their passions, fears, and hopes as if they were characters in an epic novel or a Shakespearian drama. In reality, they’re largely creatures of habit acting out genetically encoded behaviors. (One could argue that humans aren’t much different, however—we simply play out our genetically encoded behaviors in a way that provides more individual freedom of movement.)

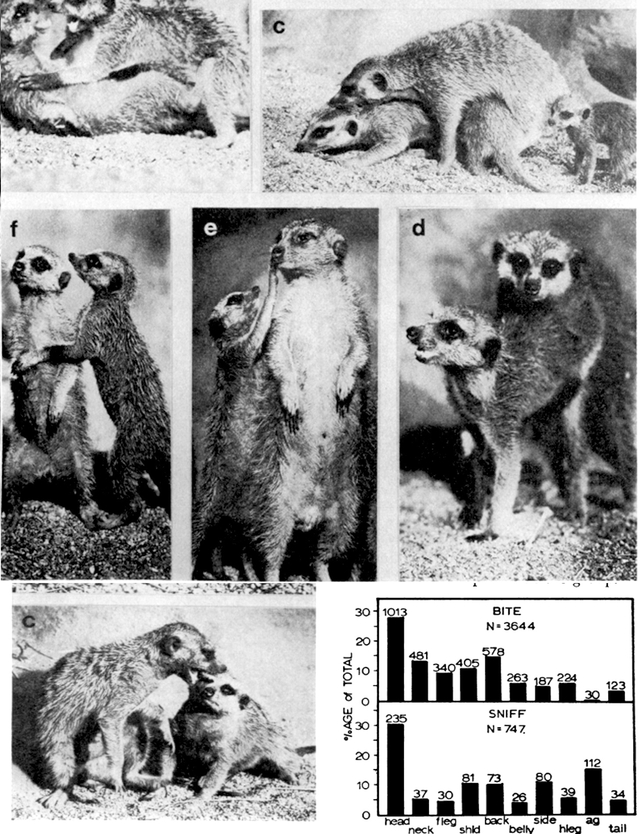

Meerkat social life from the quantitatively-inclined perspective of zoologists, 1974. (Note the graph of bites and sniffs). C. Wemmer and M. J. Fleming, “Ontogeny of Playful Contact in a Social Mongoose, the Meerkat, Suricata suricatta,” American Zoologist Vol. 14, No. 1 (Winter, 1974).

And yet I firmly believe that meerkats and other higher-order mammals do have a history, of a sort. I’m not talking about the natural history of biologists, which is concerned with their average lifespan, their feeding habits, their reproductive cycles. I mean the history of historians. This type of history, the kind I enjoy doing and reading, is grounded in imaginative leaps that bear a core resemblance to those of the novelist or poet. It’s about putting your own experience of the world to one side and trying as hard as you possibly can to imagine someone else’s experience. What is it like to live in a meerkat society? On what internal principles do they organize themselves? What do they dream about? When they gather in the desert at night and make high-pitched sounds as a group, are they singing? What is meerkat subjectivity? To paraphrase philosopher Thomas Nagel, what is it like to be a meerkat?

This is a history of animals that has yet to be written. But scientists are increasingly brushing up against its edges, every year making new discoveries about the outer limits of animal intelligence. As it grows ever more clear that non-human brains can experience emotion, remember, dream, and even reason, the need for a new kind of animal history becomes obvious.

Animal history, to be sure, is already a burgeoning field. Many recent works of animal history have been innovative and even brilliant: I’d single out Sam White’s “Capitalist Pigs,” Virginia De John Anderson’s Creatures of Empire, Peter Sahlins’s work on the menageries of the French Enlightenment, and Donna Haraway on primates. But they continue to chart animal histories only insofar as they influenced human histories. Perhaps there’s room now for a type of history that moves smoothly between the natural history of the life sciences and the more individualistic narratives of historians—and between human and animal subjectivities.

Who will write it?