Letter from the Editors: Digs

Lyntha Scott Eiler, “Navajos at an Archaeological Dig in Arizona,” Environmental Protection Agency, 1972 (via Wikimedia Commons)

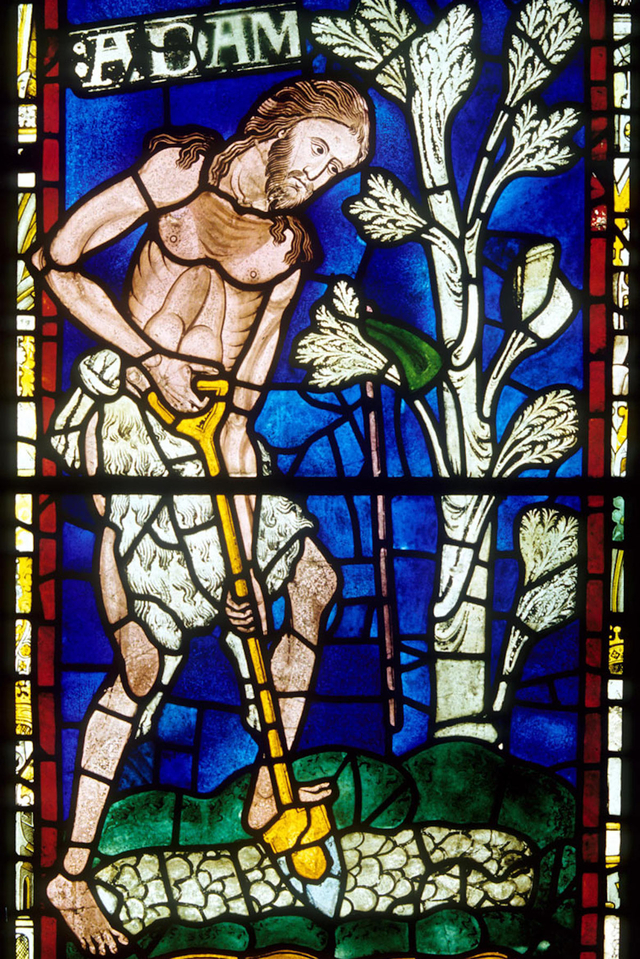

When Adam delved and Eve span

Who was then a Gentleman?

—John Ball, 1381

When the itinerant “hedge priest” John Ball shouted these words to English peasant rebels in June of 1381, they provoked a riot. Inspired by Ball’s vision of a world before laws and social hierarchies, his audience rushed into the Tower of London and killed the Archbishop of Canterbury. Less than one month later, Ball, too, lay six feet under.

Why did the simple image of a man digging hold such resonance?

“Cursed is the ground for thy sake,” God had rebuked Adam in Genesis. “In sorrow shalt thou eat of it all the days of thy life.” Early depictions of Adam and Eve fixated on this image of earth, toil, and mortality: a post-Eden Adam is often shown sweating with a shovel or spade. To be fully human is to struggle with the earth, these images seem to say—and also, eventually, to return to it.

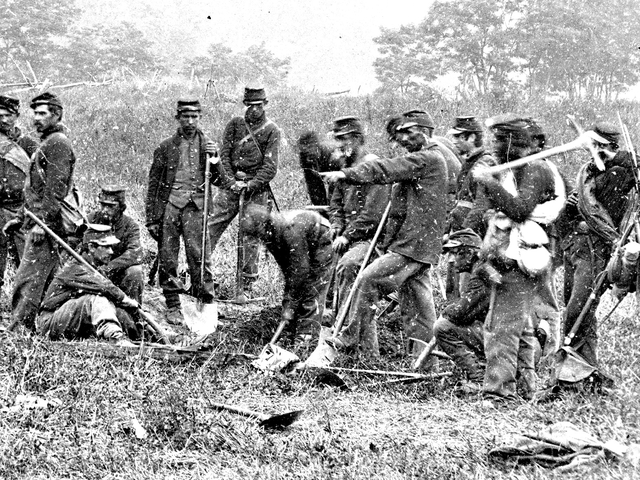

There’s something to this. Not all human societies are agricultural, but all depend upon our abilities to transform the ground we walk on. Digging, excavating, burying, foraging, and uncovering are core human traits.

The articles in Chapter One of this issue are about digging in its most concrete and earthy sense. We begin with an archaeologist, Carla Klehm, who shows how a handful of glass beads found in the red soil of Botswana can reconstruct centuries of buried history. Next Allison Bigelow explores the silver veins of Potosí, perhaps the most important mine in world history, while artist Justin Berry experiments with the images from one of the first printed mineralogical texts: what do they look like stripped of miners? A pair of articles debate whether the humble digger of the Kalahari desert, the meerkat, can be said to have a history, while contributions from graphic novelist Jim Ottaviani and fiction writer Michele Stepto round out the chapter.

It is no coincidence that an alternate meaning of “to dig” is “to know, understand or appreciate”: etymologically, this double sense harkens back to a conceptual link between excavating and understanding. Chapter Two confronts digging as a form of exploration. Julia Gaffield describes how she unearthed Haiti’s long-lost Declaration of Independence, which made international news in 2010. Dan Buck sifts through the fragments of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Josi Ward traverses the dusty towns around California’s Salton Sea on the lookout for fast-fading traces of the migrant labor camps of the 1930s. Corinne Lampert brings us a tale of digging in the Lucca archives, and the talented Kevin Cannon returns with another cartographic biography, this time of a pioneering female archaeologist. Sometimes the passage of time itself can be a form of burial, as Charles Shaw documents in a spectacular article and group of photos documenting the fading Soviet triumphalism of a Moscow park. Finally, three poems from Molly Brodak elegize the death of a geologist and “the romance of bones.”

In nineteenth-century Australia, gold miners began foregoing tents and instead started digging hobbit holes for themselves in the loose sands of the Outback. They took to calling these their “digs,” and an alternate sense of the word, as a form of lodging, was born. Chapter Three rounds out the issue with articles on lodgings, like Kate Duffy Osheim’s beautiful portrait of Philadelphia’s ruined Eastern State Penitentiary and Darrell Hartman’s review article about the eternal homes of the pharaohs and those who sought to uncover them. But digs can also be insults—taking a dig at someone has a long history which is traced in our “Historical Digs” piece, and in Erika Bsumek’s profile of the painter George Catlin and the disastrous consequences of his portrait of a Lakota warrior named Mah-tó che-ga.

Digging may seem like the simple act of moving dirt, but it has deep resonances. We hope our excavations of the word are entertaining and edifying, but above all that they inspire you, our reader, to go digging yourself. Maybe the late Seamus Heaney put it best, as he contrasted the memory of his father cutting peat on a rainy day in Ireland, 1966, with the more poetical earth he delved:

Between my finger and my thumb

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

Your Appendix editors,

Benjamin Breen

Felipe Cruz

Christopher Heaney

Brian Jones

Amy Kohout