Haiti’s Declaration of Independence: Digging for Lost Documents in the Archives of the Atlantic World

Editor’s Note: A Haitian Kreyòl version of this article is available here.

On the first of January, 1804, Haiti became the second independent nation in the Americas. The Haitian Declaration of Independence was the triumphant culmination of the only successful slave revolution in history. The content of Haiti’s Declaration became well-known thanks to transcriptions and later printings, yet all copies of the official government-issued document disappeared from view in the decades following the revolution. Unlike the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, which has a deep history of symbolic significance as a material object (just ask Nicholas Cage), the physical text of Haiti’s Declaration fell into obscurity. By the late nineteenth century, no official copy could be found of the document that introduced Haiti on the world stage and announced a citizenry united as one people: Haytians.

In 1903, on the eve of Haiti’s centennial, the Haitian newspaper Le Soir issued calls to the government and to Haitian citizens to help find the original Haitian Declaration of Independence, “the baptismal certificate of the Haitian people.” According to the editor of the journal, Justin Lhérisson, the Declaration of Independence was an essential focus for the celebrations and it had to be found as a re-affirmation of 1804’s importance.

Surprisingly, these early efforts to rediscover the Declaration failed.

“The Haitian Declaration of Independence,” Le Soir reported on January 28, 1903, “by a culpable negligence, cannot be found in the Archives of the Republic. Some say it was stolen and sold in Germany, others say that it is in England.” The next day, Le Soir printed a letter from “a longtime subscriber” that supported the newspaper’s calls for the Haitian government and Haitian citizens to search for the original Haitian Declaration of Independence. The letter suggested that someone had sold the document to a German in the 1860s and that the German had then donated it to a German museum. Although no evidence was presented to support this claim, it seemed entirely possible since German immigrants arrived in Haiti in significant numbers in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Three years after the centennial anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the Declaration itself remained lost. The Secretary of the Legation of Haiti in London, Félix Viard, wrote to Lhérisson asking for guidance in his continued quest to find the document. Viard was certain that it was not at the British Museum since he had searched the museum’s “department of historical documents and famous autographs.” In looking for a document signed by Jean-Jacques Dessalines and the other leading Haitian generals, Viard mentioned that if he found the document, which he argued would “be more in its place in our National Archives,” he would photograph it with “50x60 plates.” Viard noted that he would send any such images to the “President of Haiti, who would surely display it in his palace.”

The mystery of the Declaration’s disappearance deepened with each passing decade. Close to fifty years later, in anticipation of sesquicentennial celebrations, Haitians were still looking for an original copy. On December 31, 1952, the Haitian intellectual Edmond Mangonès wrote to The Haitian Commission of Social Sciences for the 150th Anniversary of Independence to report the results of his search to find an original copy of the Declaration of Independence. “All searches to date have been in vain,” he wrote. Mangonès knew about the efforts of earlier researchers but reported that no one had been able to find “the original Declaration or even a signed copy or a printed version from the time.” Mangonès remained hopeful, however, that a printed copy might exist, since the famous Haitian historian Beaubrun Ardouin noted that “all the documents published at Gonaives” were “printed … and sent to all of the secondary officials and occasioned public festivals.”

Mangonès attributed the disappearance of the original Haitian Declaration of Independence to “the ostracism that struck Dessalines during 39 years—from 17 October 1806 [the date of his assassination] to 10 December 1845, the date that President Pierrot used the law that recognized the services rendered to the Nation by the Emperor [Dessalines] to rehabilitate his memory.” President Louis Pierrot was, in the words of historian Erin Zavitz, a “nationalist and noiriste black general,” who had “decreed a national funeral service for Dessalines on 17 October.” Despite this rehabilitation of Dessalines’s memory in the mid-nineteenth century, Mangonès lamented that “we do not have a copy nor even a printed text of our Declaration of Independence that was consecrated by a verbal proclamation.” Mangonès was frustrated by the haphazardness of his research and regretted that the government had not taken a more active role in commissioning archival research. He also called for a broader exploratory research mission that would try to remedy the fact that Haiti’s important historical documents were scattered throughout the country and in foreign archives.

Over two centuries had passed since Haitian leaders had proclaimed the Declaration of Independence when I set out to write my dissertation at Duke University on the early independence period.

At first, I was confronted by countless specialists who cautioned me, “but, there aren’t any sources.” Fortunately, my advisor Laurent Dubois supported my project despite the alleged paucity of sources about the tumultuous decades after the Haitian Declaration of Independence. It is widely known that texts from the earlier period of the Haitian Revolution can be found in French archives but, as implied in the newspaper’s comment about “negligence,” the Haitian state did not have an official archive until the mid-nineteenth century. Other factors, such as natural disasters, under-funded institutions, political turmoil, and theft have also worked against the proper curation of official archives in Haiti. Nonetheless, a number of repositories have maintained important parts of Haiti’s archival record. The Archives Nationales d’Haïti (est. 1860), the Bibliothèque Nationale d’Haïti (est. 1939), the Bibliothèque Haïtienne des Pères du Saint-Esprit (est. 1873), the Bibliothèque Haïtienne des Frères de l’Instruction Chrétienne (est. 1912), and the Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien (MUPANAH) (est. 1983) all have rich archives, although their collections relate mostly to the latter half of the nineteenth century and twentieth century.

I quickly realized, therefore, that I would have to re-think the typical archival strategy for graduate students, in which you spend a year or two in one country reading everything you can get your hands on in the relevant archives and libraries. My study of the early years of Haitian independence could not be based exclusively on research in Haiti.

Instead, I planned for shorter trips to seven different countries—Jamaica, Great Britain, France, the United States, The Netherlands, Denmark, and Haiti—and I found relevant documents in every archive that I visited. I had some luck along the way, but my strategy was part of a larger scholarly shift that emphasizes the interconnectedness of the Atlantic World. Rather than histories divided by nationalities, an increasing number of studies are revealing how the movement of people, goods, and ideas created an integrated Atlantic community. The fact that Haitian documents ended up in archives in many countries makes complete sense from this Atlantic World perspective on Haiti’s history.

The Haitian Revolution involved armies from the French, British, and Spanish Empires as well as armies of slaves and former slaves and free non-white colonial residents. Alliances changed throughout the war, but it was an international affair from the very beginning. Participants in the war as well as onlookers had a vested interest in the success of one or more of the many sides of the fight so they collected and shared news about the Revolution. Furthermore, the Revolution led to the migration of thousands of people from Saint Domingue (Haiti’s colonial name) to other colonies, the United States, and Europe. Because of this, I have found that sources relating to the Haitian Revolution are not only held in French archives, but are scattered (though not randomly) throughout Europe and the Americas. International interest and involvement in Haiti did not stop after Declaration of Independence.

My first international research trip was to Kingston, Jamaica, inspired by what the famous Haitian historian Thomas Madiou wrote about a treaty negotiation between Governor-General Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Governor George Nugent of Jamaica in early 1804. Since the historiographical emphasis has been on Haitian isolation after independence, the mention of these negotiations sparked my interest. No finding aids were available so I arrived in Kingston with only a hunch about what I might discover in the collections.

It turns out that luck was on my side. “I almost cried tears of joy in the archives,” I wrote to a friend one day. At the National Library of Jamaica (NLJ), I found three large wooden boxes (maybe 2.5 by 1.5 feet) containing all of the correspondence of Governor Nugent. This correspondence revealed that in the months leading up to and after the Haitian Declaration of Independence, Nugent had sent emissaries to Saint Domingue/Haiti to try to negotiate a trade treaty with Dessalines. The boxes of documents showed that these negotiations were much more extensive and significant than Madiou had realized. These documents would soon play a central role in helping me solve the mystery that had defied concerted efforts for more than a century.

My research led me to one of Nugent’s agents, Edward Corbet, who brought a copy of the Haitian Declaration of Independence to Jamaica. Corbet had written to Nugent and noted that he was enclosing a printed document. “I now beg leave to lay before your Excellency,” he explained after returning from Haiti, “their declaration of Independence. This piece wherever it may have been composed, was not published ‘till after my arrival at Port au Prince, for the Copy I have now the honor of presenting to you had not been an hour from the press.” This document proved to be highly significant, although not immediately. In the archival boxes, I did find a handwritten transcription of the Haitian Declaration of Independence. However, given the fact that other handwritten and printed versions exist in several repositories, the document itself was not an important discovery for early Haitian history.

What had happened to the Declaration of Independence that “had not been an hour from the press”? In reflecting on this question, I discussed the possibilities with one of my dissertation committee members, Deborah Jenson, who had earlier researched the publication of the Haitian Declaration of Independence in American newspapers. We concluded that Corbet must have been referring to a printed document and not to the handwritten transcription that I found at the NLJ; therefore something must have happened to the official copy that Corbet noted as having just arrived from “the press.”

The success of my research trip to Jamaica fuelled my suspicion that Haiti’s archival record reflected its key role in the larger Atlantic World. The next step was to fly to London in search of additional correspondence relating to Nugent and Dessalines’s negotiations, including mentions of attachments, like the Declaration of Independence, that were not in the boxes at the NLJ. The colonial correspondence at The National Archives of the United Kingdom (TNA) is first organized by colony and then by chronology. I started my research in the Jamaica series, CO 137. It was not long before I found a packet of printed Haitian documents that Governor Nugent had sent to the British ministers in London on March 10, 1804. “I beg leave to transmit to your Lordship,” Nugent wrote to the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, “every paper in my possession, which can tend to throw a light upon the subject.”

This packet included a number of new and exciting documents that, if ever studied, had never been used before in published research, such as the only known version of a song titled Hymne Haitiène, composed and sung in January 1804.

But most significantly, and much to my amazement, the packet of documents also included a printed copy of the long-sought Haitian Declaration of Independence, issued by the Government printing press in Port-au-Prince.

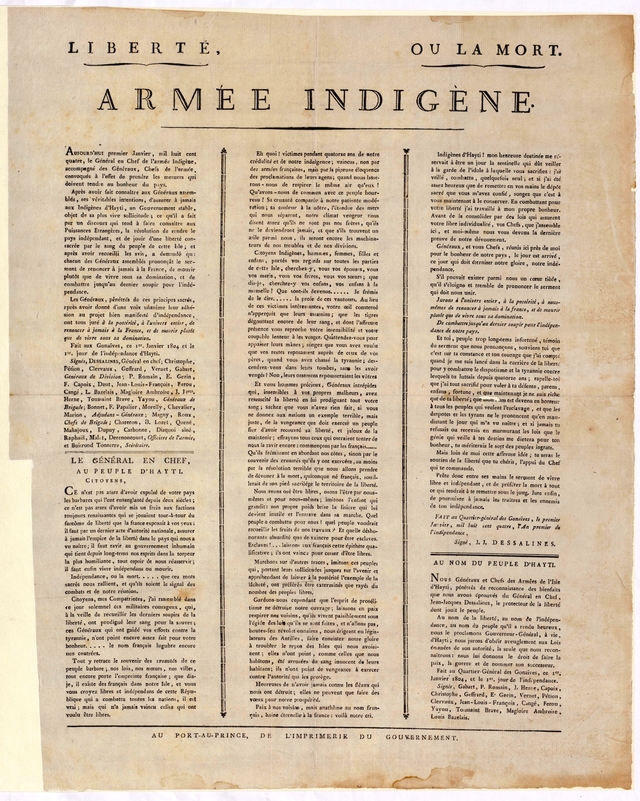

The official Declaration of Independence was an eight-page pamphlet with the words LIBERTÉ OU LA MORT written boldly across the top of the first page. The format of the document suggests that the Haitian government intended to mail it to local and foreign governments. The document is composed of three parts:

1. the Acte de l’Indépendance (Declaration of Independence)

2. a proclamation by the General in Chief, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, to the people of “Hayti,” and

3. the nomination of Dessalines as the Governor-General of Haiti.

While the document was printed in Port-au-Prince, the Haitian Declaration of Independence was first proclaimed as a speech at Gonaïves. Since the evidence that I found in Jamaica revealed that Corbet had brought the pamphlet to Jamaica around January 21, 1804, we can conclude that the text of the document, composed by Louis Félix Boisrond-Tonnerre and commissioned by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, would have been carried the seventy miles from Gonaïves to Port-au-Prince in the two or three weeks after January 1, 1804.

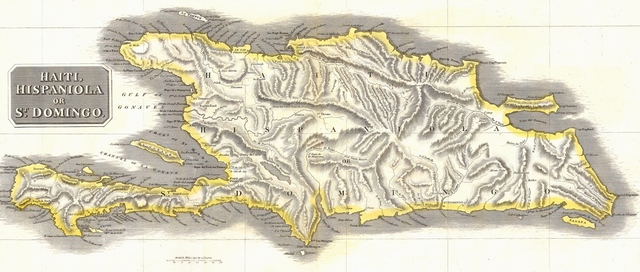

John Thomson, “Haiti, Hispaniola or St. Domingo” (1815), detail. David Rumsey’s Historical Map Collection

I wrote to Deborah Jenson and Laurent Dubois about what I had found and their enthusiastic responses fuelled my continued work in the archives. But, as is often the case with historians (and maybe academics more generally), I did not immediately recognize that anyone beyond specialists in the field would care about my discovery of the long-sought Haitian Declaration of Independence.

A few weeks later, Laurent emailed me to report that he had spoken with the Haitian archivist, Patrick Tardieu, who confirmed, after examining the digital copy of the document that I had made in the archives, that this was indeed the first official copy of the Declaration of Independence to be discovered since sometime in nineteenth century.

At this point I began to realize that more than specialists might care about my discovered, so I updated my Facebook status to share this news with my family, friends, and colleagues (these days I would have tweeted the news!). A friend of mine, Jacob Remes, immediately commented that I should contact the Office of News and Communications at Duke University because he was convinced that many people would be interested, especially because Haiti was constantly in the headlines at the time since Haiti had been devastated by a magnitude 7.0 earthquake less than a month earlier.

It turned out that Jacob was right and indeed to an extent that was beyond all expectations. The story quickly spread around the world, broadcast on news networks and printed in over 50 national and international news sources. Journalists immediately connected the discovery to current events and expressed hope that this positive news might help Haitians during their current crisis. “That the document would be found in February,” Damien Cave wrote in The New York Times, “just weeks after the earthquake that killed so many; that its authenticity would be confirmed in time for the donor conference that could define Haiti’s future—some see providence at work.” While Cave focused on the potential implications going forward, Siri Agrell of Canada’s Globe and Mail highlighted the importance of historical memory in times of need. “But her discovery,” Agrell reported,

which comes more than 200 years after the document was signed and ends decades of historical sleuthing intent on its recovery, could not come at a more poignant moment for the nation of Haiti, still reeling from the latest blow to it national identity. Struck by a devastating earthquake in January, the country is struggling to rebuild, and historians say the document will serve as a much-needed reminder of what has already been overcome.

What I appreciated most about the international public reaction was the obvious hunger for an alternative narrative of Haiti, one that emphasized the global significance of its achievements during and after the revolution. Cave’s article quoted Leslie Manigat, a Haitian historian and former president. “In the context of the Haitian tragedy,” Manigat argued, “it is important for Haitians and the rest of the world to remember the independence of Haiti.” It was a chance for a public audience to talk about something other than Haiti’s recent political turmoil, devastating poverty, and the destruction of the earthquake.

“‘We must recover,’ [Manigat] said, shouting in order to be heard through a phone in Port-au-Prince that cut out repeatedly. ‘We must find an alternative to the traditional meaning of independence, now, in the new world.’”

Just over a year after my initial trip to the archives in London, I returned to complete my dissertation research by investigating the holdings of the Jamaican Admiralty records in The National Archives. Much to my surprise, I found another type of printed copy of the Haitian Declaration of Independence, a one-page broadside intended for posting in public places. In this case the document had been removed from the Admiralty records and re-cataloged as a map so that it would not have to be folded in the bound volume.

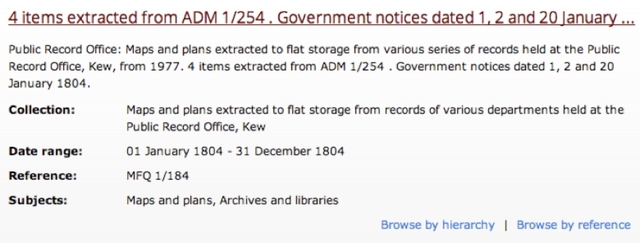

This second discovery emphasized one of the key explanations for why all the previous efforts to find an official copy of the Haitian Declaration of Independence had failed. Both extant versions are located in unexpected archival locations; unexpected, of course, unless we recognized the complex and integrated place that Haiti occupied in the Atlantic World in the nineteenth century. In this second case, to order the document you have to enter MFQ 1/184, not MFQ 184 as the removal slip notes. The catalog entry for the broadside printing of the Haitian Declaration of Independence does not even mention that the document is from Haiti (despite the fact that it is cataloged with three other important Haitian documents).

The online catalog entry for the second newly-discovered Haitian Declaration of Independence. National Archives, U.K.

I have submitted multiple requests for the document to be re-cataloged and removed from circulation (in keeping with the fact that the pamphlet version was removed following my discovery of it from the Jamaican colonial record and has now been placed in secure holding for preservation).

Like Justin Lhérisson and Félix Viard in the early twentieth century and like Edmond Mangonès in the mid-twentieth century, Patrick Tardieu has renewed the calls for the government to send an official delegation to London to research the archival treasures relating to Haiti’s history. He recently wrote an article on one of the other documents that is cataloged with the broadside Declaration of Independence in an effort to emphasize the number of undiscovered sources that relate to Haiti’s history. “In presenting to the Haitian public this ordinance from January 20, 1804,” Tardieu wrote in the Haitian newspaper Le Nouvelliste, “I once again appeal to the authorities of the country. A cultural mission imposes itself on the banks of the Thames; Her Majesty’s Ambassador has he not made a formal invitation to the Haitian government in 2011? Are there other previously documents in the archives of London? Only an official mission will tell.”

The story surrounding my discovery of the two government-issued printed copies of the Haitian Declaration of Independence highlights the ways in which historical research is connected to contemporary scholarly trends and to current events. The Atlantic “turn” is helping to reveal the interconnectedness of empires, colonies, and countries in the early modern period. Historians are beginning to conduct their research in new ways, traveling to archives in multiple countries and researching in several languages. These new methods have encouraged an explosion of new discoveries in the Haitian history.

The scholarly interest in Haiti’s history, however, is also a result of contemporary political, economic, and earthquake-related issues. Historians and scholars in other disciplines have sought to complicate the characterizations of Haitian history as a linear path from revolution to twenty-first century poverty. Furthermore, the fact that Haiti was already in the news meant that far more people paid attention to my discovery. The messages and feedback that I received in the days following the news of my discovery emphasized feelings of pride and interest; many were overjoyed at the opportunity to reconnect with this important document while others were grateful to read it for the first time.

What also became clear are the lasting bonds between Haiti and the United States as the first two independent countries in the Americas. As Rachel Maddow noted on her MSNBC primetime show, with her index and middle finger crossed, “us and Haiti, we’re like this. We always have been.”

Editor’s note: This article is available in a Haitian Kreyòl translation by Marie Lucienne Megie: click here to read it. For further information on the Haitian Declaration of Independence, visit http://haitidoi.com.