Days of Future Present: Marvel Comics and “the Most Intricate Fictional Narrative in the History of the World”

I. Apocalypse Later

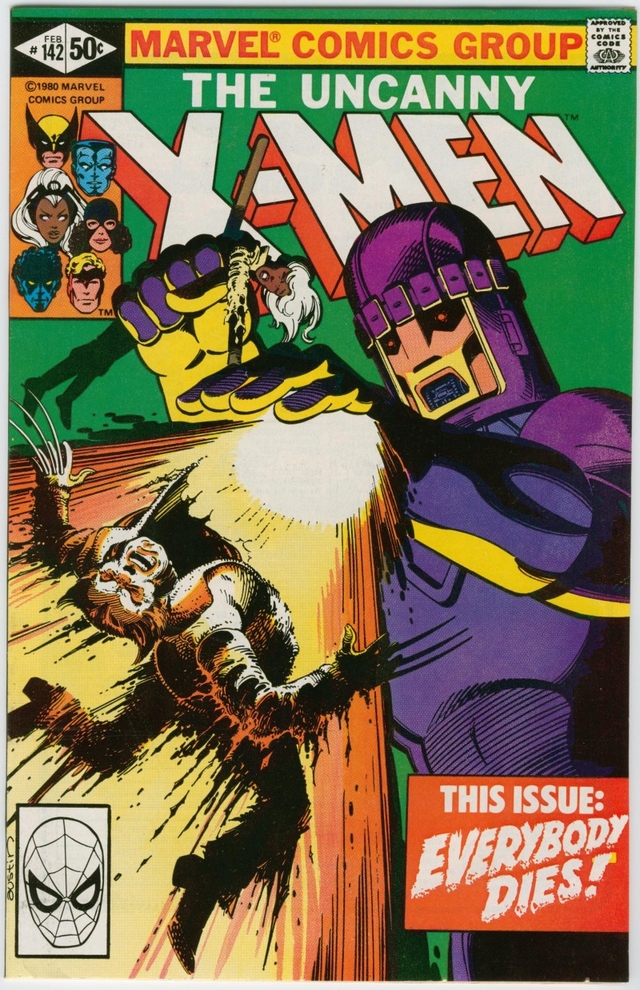

For just over half a century, there’s been another America running alongside our own, where colorfully dressed misfits solve crimes, protect the weak, and have explosive misunderstandings. One team of those misfits is more outcast than the rest, and since 1980 they’ve been fighting to avoid a 2013 where airborne robots assassinate the state’s enemies; where scientists map the genes of fellow citizens without their permission; where New York is partially abandoned and has interment camps in South Bronx.

“In North America, in the year 2013, there are three classes of people,” the team’s most sympathetic chronicler once explained:

“H,” for baseline Human—clean of mutant genes, allowed to breed. “A,” for Anamolous [sic.] Human—a normal person possessing mutant genetic potential … Forbidden to breed. “M,” for Mutant. The bottom of the heap, made pariahs and outcasts by the Mutant Control Act of 1988. Hunted down and—with a few rare exceptions—killed without mercy. In the quarter-century since the act’s passage, millions have died. They were the lucky ones.

This pulpy self-seriousness, of course, is the world of Cyclops, Wolverine, and Storm—the mutant heroes of Marvel Comics’ X-Men, the most popular title published by America’s top-selling comic book company. This bleak 2013 was a storyline named “Days of Future Past,” created in 1980 by the writer Chris Claremont and the artist John Byrne. And from the safety of our 2013, we can breath easy, relieved that we live in a world without drones, genetic screening, and a devastated Manhattan.

Because these are just comic books, right?

II. What’s So Funny About Truth, Justice, and the American Way?

In 2012, a year when the film industry’s biggest box-office smash was Marvel’s superhero epic The Avengers, which made over $1.5 billion worldwide, it’s almost trite to consider superheroes in their original, comic book-form. Superhero comics have been over-analyzed nearly since their inception in the late 1930s, but their mainstream acceptance and deconstruction in the last fifteen years is astounding: museum exhibitions, debates over their relationship to Occupy Wall Street, even Pulitzer Prize-winning novels devoted to their emotional minutiae. Each spring and fall brings a new New York Times-reviewed narrative history of some corner of the industry—a clockwork regularity that might make even the most devoted fan, the guaranteed market for these sorts of books, say, ‘So what?’ Do we really need another paean to how a particular artist drafted Wonder Woman’s boots with both strength and sexuality?

Of course we do. Superheroes are not our modern gods, as the breathier among us claim. They’re far more complicated than that.

Superheroes were created by twentieth-century individuals we can identify and interview, yet most are owned by large corporations that sought new creators when the originals got wise. This makes them one of the strangest continuous fictional experiments ever, as if Jane Austen sold Pride and Prejudice’s Elizabeth Bennett, then was replaced by a mixture of jobbers and geniuses that kept extending her adventures into the present.

Despite that corporate ownership, superheroes on a day-to-day level are constantly being re-appropriated. Fans, taxi drivers, families, and artists refashion t-shirts, tattoos, stickers, and custom-made costumes into personal icons and alter egos. One never dared dress up as Zeus: children and adults from Rio to Rochester don the mask of the Bat. Or the smile of The Joker.

Larry Tye, Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero. New York: Random House, 2012.

Two great histories of superhero comics came out in 2012 and they help explain how this happened: Larry Tye’s Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero (New York: Random House, 2012) and Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story (New York: HarperCollins, 2012). Look past their breathy titles—a convention of superheroes and mass-market histories—because their contents are worth considering.

Under the guise of a biography of the first and most superpowered hero, Tye’s Superman offers the moving story of the character’s creation by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. Tye lays out what many already know, that Siegel and Shuster got a raw deal when they sold their red and blue Kryptonian sweetheart to National Allied Publications for $130 in 1938, but digs in deep to the ‘how’ of it all. Yet Tye also shows how corporate ownership by DC Comics ensured Superman’s greatest strength as a character and as intellectual property: endurance, the ability for new creators to step in, leave their mark, and move on, without killing him (for good). It makes Superman a creative and corporate bellwether for American history, and Tye follows him through the years.

Sean Howe, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story. New York: HarperCollins, 2012.

Superman is excellent, but Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics is more free-wheeling, and has a more ambiguous ending. Thoroughly ‘unauthorized,’ Howe interviewed more than 150 individuals and their relatives who worked with Marvel between 1939 and the present, many of them disillusioned. Axes got ground, thrown, and lodged in the chests of industry greats, in the most professional, and entertaining, manner imaginable.

There are four ways to write the history of superhero comics, Howe shows, but none of them leaves Marvel, and its stewardship of its heroes, looking great. Whereas Superman and his companions at DC—Batman, Wonder Woman, the Flash—always return to their clearly defined archetypal cores, Marvel’s heroes, at least in comic books, got lost along the way.

III. Along Came a Spider

The first way of telling the history of superhero comics remains the most traditional. This is the ‘superhero genesis tale’. It begins when a cape hits it big, then unravels when the superhero’s creators and owners begin to quarrel. Legends have been staples since 1938, when those two good Jewish boys from Cleveland, Siegel and Shuster, channeled their sense of alienation, parental loss, and justice into Superman, and then sold him. The bickering began early, and by 1962 Siegel began threatening DC with a lawsuit.

The early 1960s were Marvel’s moment, however, when the company was ground zero for the creation of now famous characters like The Fantastic Four in 1961; Spider-Man and the Hulk in 1962; Iron Man, the Avengers, Doctor Strange, and the X-Men in 1963, Marvel’s annus mirabilis; and Daredevil in 1964.

It’s here that Howe’s book begins in earnest, teasing out the artistic collaborations that gave these characters life. The two central figures are the writer Stan Lee and the artist Jack Kirby, born Stanley Martin Lieber and Jacob Kurtzberg. Both were Jewish, both changed their names, both grew up poor in New York—but the resemblance ended there.

Born in 1917, Kirby had a few years on Lee, and learned how to draw and scrap in the Lower East Side slums. When he started in comic books in 1939, he came out swinging. In late 1940, a year before the United States got into World War II, Kirby and his fellow artist Joe Simon co-created the character Captain America for Timely, Marvel’s precursor. They introduced him with one of the most famous covers in comic book history: Captain America clocking Adolf Hitler in the face.

For their second issue, Simon and Kirby sent the hero and his sidekick Bucky to infiltrate a concentration camp in Germany. Howe perfectly captures Simon and Kirby’s mixture of urgency and New York snarl: “‘Don Yankee schwein vood upzet mein plans,’ Hitler worried, before Bucky kicked him in the stomach.” Kirby enlisted during the war, and attended the liberation of a small concentration camp.

Lee also began at Timely in 1939, but his job, at first, was to make sure the inkwells were filled. In his earliest days he wore a propeller beanie to the office, and tootled about on an ocarina, bugging the older artists. Lee was savvy, though, and moved on to writing, spending WWII producing copy for the army. He and Kirby both survived the comic book industry’s collapse in the 1950s by working across genres.

Lee says he was thinking about quitting when his publisher, Martin Goodman, told him to come up with a superhero team to compete with DC’s Justice League of America. He delivered the idea for the Fantastic Four, whose powers were as hideous as they were unique, and whose relationships resembled that of a very dysfunctional family. Kirby came up with the characters’ iconic designs, the exploding blocky action, and, frequently, the story’s inner beats. Lee then came up with the dialogue—a process they called ‘the Marvel Method.’

This is all the stuff of legend, and Kirby’s partisans and Lee’s defenders—of which there are fewer—fight over their contributions like Beatle fans argue over John and Paul. Howe, though, is unstintingly fair. Lee comes across as self-conscious, self-promoting, and cheerfully cornpone, but with a real knack for coming up with clear concepts that artists would then give life: the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, the Avengers, and the X-Men with Kirby, the jittery, fragile Spider-Man with the Ayn Rand-obsessed Steve Ditko, and Daredevil with Bill Everett.

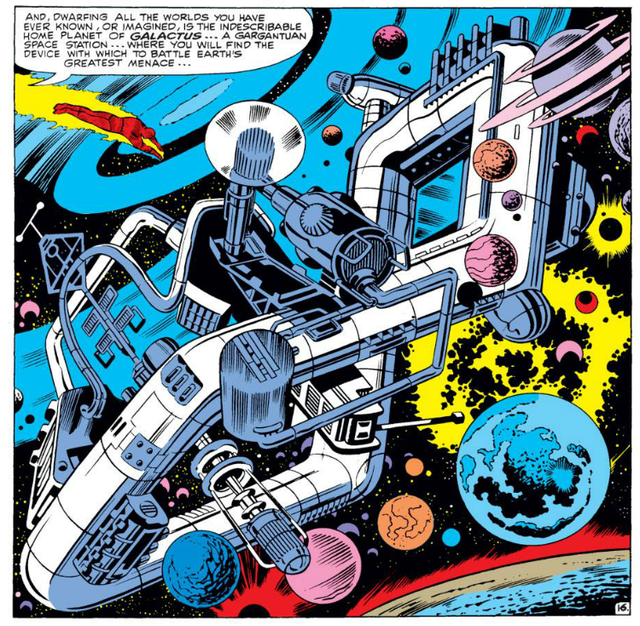

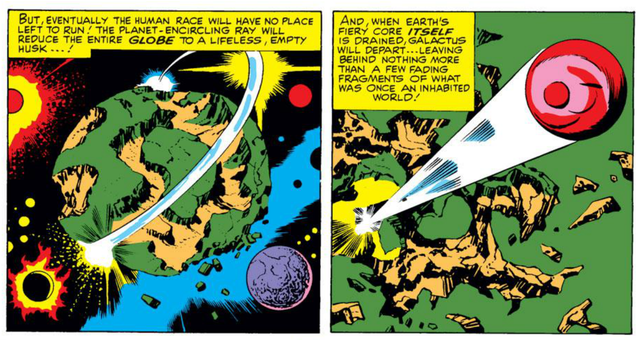

Jack Kirby (penciller), Joe Sinnott (inker), Stan Lee (writer), “If This Be Doomsday!” The Fantastic Four Vol. 1 #49 (Apr., 1966).

Kirby comes off as the most inspired, especially as he pushed his art toward increasingly futuristic galactic epics and the other side of doomsday. Lee worked him hard, however, and did little to disabuse the public of the notion that he, Lee, was the flame. It’s hard not to feel that Kirby, the exhausted, cigar-smoking workhorse, got a pretty bum deal before he left Marvel in 1969 for DC—the Distinguished Competition, in fanboy terms. Kirby cut loose with a whole raft of more cosmic characters, and it was clear that Marvel had nurtured him, then held him back. Yet the characters were so aggressively weird that many readers couldn’t relate. That was what Lee had contributed: accessibility and that buzzword, ‘relevance.’

IV. Marvel-ous Mystery Tour

‘Relevance’ is the second way into the history of comics, and it’s also the second oldest: what are all these superheroes really about, and why do so many fans care whether they live or die? When one Cornell student gushed to Esquire in 1965 that “Marvel often stretches the pseudoscientific imagination far into the phantasmagoria of other dimensions, problems of time and space, and even the semi-theological concept of creation,” did he mean it?

Howe poses the question, but knows better than to fully throw himself into the answer. Academics and critics have been pulling their hair out about comics since the 1940s, when an otherwise well-meaning liberal psychiatrist named Frederic Wertham launched a crusade against comic books’ purported antisocial revenge fantasies, delusions of grandeur, and homosexual subtexts.

That story is well told elsewhere and Howe lingers just long enough to set the stage for Marvel. He recaps how Wertham’s witch-hunt destroyed careers and turned the industry to self-censorship. The latter turn wasn’t all bad, given that several of the comics under scrutiny were indeed violently misogynistic, but it muzzled creativity, and led to the most milquetoast era in comic book history. Superman was very popular.

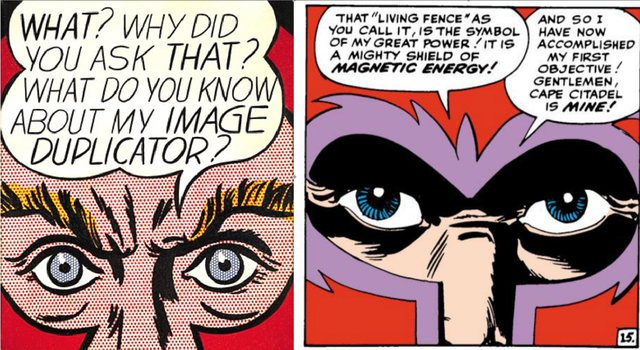

The early 1960s, by contrast, were exactly the right moment for outsider heroes, atomic and cosmic origins, and literary pretensions. Readers loved Marvel’s creations, and so did critics and ‘real’ artists. Federico Fellini (a keen cartoonist himself) stopped by the office, Roy Lichtenstein swiped Kirby’s art for his paintings, and columnists at the Village Voice considered Peter Parker’s insecurities amidst “phallic-looking skyscraper towers.” Lee got hip to the college crowd and re-branded Marvel as a “Pop Art Production.”

Roy Lichtenstein’s Image Duplicator, 1963, left, borrowed from the panel at right, from Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s “X-Men,” The [Uncanny] X-Men Vol. 1, # 1 (Sept. 1963).

Howe shows that Lee got the joke. Academics working on any sort of pop culture should read Stan Lee’s response to a question from one reader as to whether—in Howe’s words—“the Galactus saga was a justification for Vietnam, with Galactus as the Viet Cong, the Fantastic Four as South Vietnam, and the Silver Surfer as America … right?”

Lee deflected: “Two’ll getcha ten that our next mail contains a whole kaboodle of letters from equally imaginative fans who are utterly convinced that Galactus represented Robert McNamara, while the Silver Surfer was Wayne Morse—with Alicia symbolizing Lady Bird!”

Howe affirms that most Marvel stories were “beyond metaphor,” but also makes it clear that Lee learned to pepper his scripts with “token liberal signifiers and general trippiness.” Iron Man began as a true cold warrior but cut back on the Red Scare talk as the decade progressed. The X-Men played out as a liberal’s Civil Rights parable, with one group of superpowered mutants fighting to win humankind’s trust and respect, and another fighting for separatism and domination. Doctor Strange explored the cosmos from the comfort of his Greenwich Village pad.

Readers turned on, tuned in and dropped money for 40 million copies in one year alone.

Business was worse in the 1970s, but it allowed even wilder experimentation. Howe’s enthusiasm for this under-appreciated era is infectious. Under an editor name Roy Thomas, a new guard of young writers and artists sent the characters on even weirder trips, and “smuggled countercultural dispatches into the four-color newsprint that found its way onto drugstore spinner racks.”

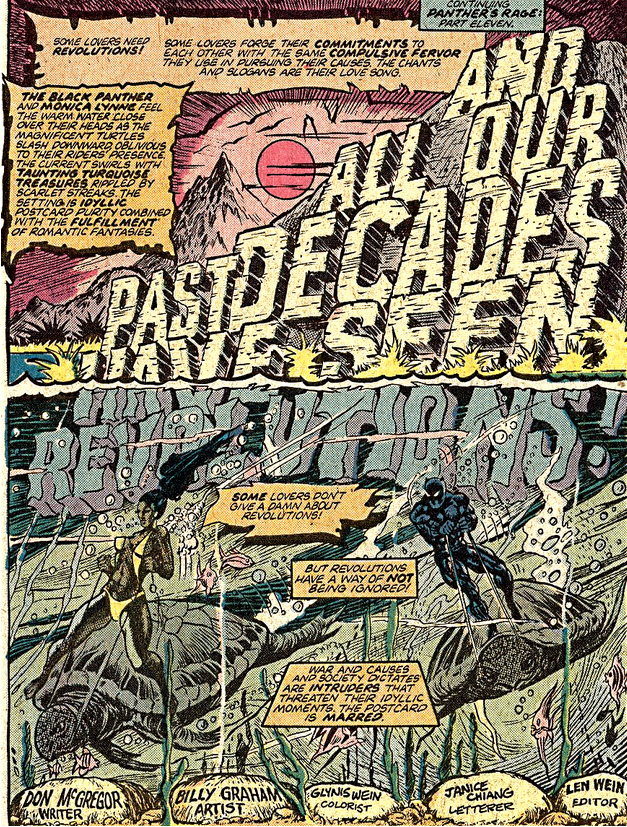

Don McGregor (writer), Billy Graham (artist), “And All Our Past Decades Have Seen Revolutions,” Jungle Action featuring the Black Panther Vol. 2 #16 (July, 1975), Marvel Comics Group.

Howe spends a fair amount of time on the Black Panther—the first black superhero, whose creation in 1966 preceded the U.S. political organization’s formation in Oakland by three months. Until 1973, the character had been little more than a noble, stereotypical foil for white heroes. That year, though, the character got his own book, and a writer named Don McGregor and artists Rich Buckler and Billy Graham, an African-American, set off flying. McGregor sent the Black Panther back to Africa, to the technologically advanced kingdom he ruled, to fight rumors that he’d become a sellout. “It was the only mainstream American comic book to feature an all-black cast,” Howe notes, and McGregor sent the character through an epic thirteen-part story as politically ambitious as it was dense.

The 1970s through the early 1980s seem to have been the cultural high-water mark of Marvel, which makes it even sadder that Howe must move on to the late 1980s through 1990s, when the comic industry and most of its characters went—there is no honest way to put this politely—in the shitter.

V. Secret Wars

It’s compelling though, because this is where the book really digs into the history of Marvel as a corporation. This is the third way to tell the history of comics, and here Howe shines: this is comics as an industry, a web of competitive businesses that take risks to incubate their employee’s ideas, while simultaneously squeezing them—and their cape-wearing avatars—for profit.

Much like Gerard Jones’s Men of Tomorrow, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story excels as a labor history. It explains how a series of publishers and owners lived for so long off artists, writers and editors that signed away their daydreams for a paycheck: it paid well, in the good times; it was hard to predict which character might one day be worth billions; and working out your obsessions with colorful avatars of mass destruction was subversive fun.

It was also awful, however. Howe’s book is full of creators warning youngsters against going into comics and resenting Marvel for their treatment. Kirby was especially jaded. When Marvel tried to get him to sign an agreement that restricted his usage rights for what little artwork they agreed to return, he refused. “I wouldn’t cooperate with the Nazis, and I won’t cooperate with them,” he said. “If I allow them to do this to me, I’m allowing them to do it to other people.” As Howe points out, even the company man Lee said, “I would tell any cartoonist who has an idea … think twice before you give it to a publisher.”

This began to look particularly attractive in the 1980s, when Marvel’s editor-in-chief, Jim Shooter, began micromanaging what had been a series of independent fiefdoms. He built massive crossovers around toy promotions, disrupting individual creators’ long-simmering storylines.

The stories sold extraordinarily well, though, helping to build the American network of specialty comic book stores that became ground zero of the comic book market’s explosion in the early 1990s. For a short while, comics became insanely collectible, and Marvel figured out how to cash in. Stories and writing were sacrificed for tie-ins, surface and style. The most popular characters were violent, surrounded by scantily dressed supporting characters. Hotshot artists like Todd McFarlane, Jim Lee and Rob Liefield attained unbelievable sales numbers, then walked off to found new companies—but not before more thoughtful longtime writers and editors had quit. Marvel competed by setting the market into a speculative frenzy over gimmicky hologram covers and pseudo-cataclysms. New incentives meant that one editor of the popular X-books walked away with $85,000 each month.

But when readers realized that not everyone’s copy of 1991’s X-Men # 1, mint with gatefold cover, would pay for a college education, the market crashed. Marvel went bankrupt and was bought out by a toy company. Countless artists, editors, and writers were out of a job. Small towns that had had three comic book stores suddenly had none.

It’s at this point that Howe’s narrative becomes suitably cynical, detailing the suits and countersuits between the company’s owners and debtors that led to Marvel’s solvency in the 2000s, and its fairly successful attempt to regain relevance with ‘mature’ content (read: sex and violence). Marvel’s aggressiveness has paid off, never more so than last summer, when their Avengers movie franchise took over the world.

Howe lets the quotes speak for themselves: creator after creator left out in the cold by Marvel and Lee, who’s happy to wave to the cameras.

Still, even if Howe is restrained, his readers don’t have to be. It’s sad that Howe only passingly mentions that “DC signed a group of black comic creators—many of whom had worked for Marvel—to produce a number of new series for the publisher, under the name Milestone.” It’s especially unfortunate given that one of those creators, Dwayne McDuffie, was one of Marvel’s cleverest critics.

In one famed internal tongue-in-cheek memo from 1989, McDuffie noted that “25% of all African-American superheroes appearing in the Marvel Universe possessed skateboard-based superpowers.” He proposed “Teenage Negro Ninja Thrashers,” a team whose every member was “a black guy on a skateboard.”

McDuffie also came up with one of the cleverest titles in superhero history. This was Damage Control, a mini-series co-created with Ernie Colón about a company that cleaned and rebuilt New York and the world for cash after every superhero’s doomsday battle.

This was good satire. Damage Control resembled Marvel itself, whose comic book strategy seemed to have become: take the beautiful world that Lee, Kirby, Ditko, Simon, and Everett created; tear it apart; re-build it as ‘brand new’ and ‘same as it ever was’; make tremendous amounts of money; repeat.

But if you were a fan of these characters—if your heart ever skipped a beat when Peter Parker discovered his powers, or a mutant found acceptance with the X-Men—Damage Control pointed at something rather unsettling. Whether or not the real world, our world, is the safest it has ever been, as some claim, the Marvel Universe was experiencing Hiroshima-scale events thrice yearly. And why would anyone want to escape to a world like that?

VI. Webspinners

The answer is the fourth way of writing about superhero comics, and Howe is brave to include it, given that it usually bores non-fans to tears: the “history” of a particular company’s fictional universe.

As Howe explains, fans love Marvel because just about every appearance of a character “counts.” In Spider-Man’s case, that means fifty years of monthly, even tri-monthly appearances in which hundreds of creators have tried to maintain his character while spinning new threads of mythos. Howe claims—rightly—that it makes Marvel the “most intricate fictional narrative history of the world.”

Too intricate, perhaps. Stan Lee once ordered that the “stories should have only ‘the illusion of change’ … lest their portrayals conflict with what licensees had planned for other media.” This was conservative, but its alternative is upsetting in other ways.

For example, Peter Parker, the awkward sixteen-year-old bitten by a radioactive arachnid, no longer exists in the comics. He is now Peter Parker, a late-twenty-something who accidentally killed the love of his life while saving her; whose best friend has repeatedly gone insane; who has fought his own forgotten clones; who lost his unborn child to an archenemy’s poison; who got mystically divorced by the Devil; who has seen his beloved Aunt die and return to life over and over and over …

Taken individually, some of these plot points were powerful. But cumulatively, they suggest that the Marvel Universe at some point became a torture chamber. Friedrich Nietzsche asked his readers to imagine how they’d feel if a demon snuck into their loneliness and told them they would have to live their life over and over again. DC might be a little more staid, but you can imagine Superman smiling and saying ‘Yes.’ Spider-Man might weep.

Jack Kirby (penciller), Joe Sinnott (inker), Stan Lee (writer), “If This Be Doomsday!” The Fantastic Four Vol. 1 # 49 (Apr., 1966)

Howe’s Marvel Comics never gets that heavy, but it hints that the company didn’t have to go as far as it did. Superhero comics have been in the personal and universal Armageddon business ever since Krypton exploded. At first, Marvel only continued the trend, if on a more personally responsible level: Peter Parker selfishly failed to prevent the death of his uncle, for example. And if the hazards Marvel heroes then faced felt more ‘real’ than in DC—“a red-skied New York City in flames, its screaming citizens dropping belongings and falling on one another”—then so did their victories. “Armageddon was nigh,” but it was always averted.

What changed all that was the X-Men.

VII. The Phoenix Effect

Writers love the X-Men for its easy central metaphor: good people persecuted by society for what they cannot change about themselves. It works as well for marriage equality today as it did for Civil Rights in the 1960s. The team comes complete with a ready-made rivalry between Charles Xavier, a white, bald Martin Luther King, Jr. analogue, and Magneto, Marvel’s (white, mutant) version of Malcolm X with, yes, magnetic powers. And since 1975, it has featured one of the most international casts of characters in comics, with heroes of just about every color: black, white, yellow, red … blue.

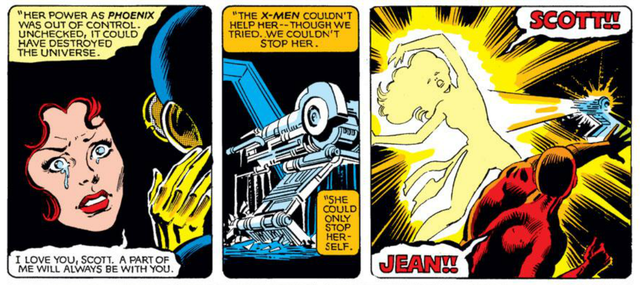

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the X-Men made some very adult questions of responsibility and guilt manageable for teenagers. The new team grappled with the death of one of its members during their second mission. Afterwards, the writer Chris Claremont and artist John Byrne merged one of the X-Men’s nicer heroes, Jean Grey, with the Phoenix, a cosmic entity that drove her to snuff out another galaxy’s sun, annihilating a nearby planet.

Claremont’s plan was that Grey would atone for her crimes, but his editor-in-chief, Jim Shooter, was apoplectic: Jean Grey needed to die. “Having a character destroy an inhabited world with billions of people,” he fulminated, “wipe out a starship and then—well, you know, having the powers removed and being let go on Earth … it seems to me that that’s the same as capturing Hitler alive at the end of World War II, taking the German army away from him and letting him go to live on Long Island.”

Claremont was furious, but when the moment came he had Jean take her own life, in a moment of clarity. Claremont and Shooter’s struggle made for sad, powerful pop art … and even better sales: the death of Jean Grey was one of Marvel’s most popular issues of all time.

Panels from Chris Claremont (writer, co-plotter), John Byrne (Co-plotter, penciler), and Terry Austin (inker), The Uncanny X-Men Vol. 1, # 138 (Oct., 1980).

It’s hard to read Howe’s book and not feel that what happened next was the beginning of the end. Hoping to reproduce the success of Jean Grey’s death, Shooter looked for more heroes to kill, and interfered more often with writers’ plots.

Claremont, meanwhile, made redemption the X-Men’s next great theme. He tried to give Jean Grey’s lover, Cyclops, some peace. He introduced a young new teenager member, Kitty Pryde, who happened to be Jewish and was soon thrust into the potential 2013 of Claremont and Byrne’s “Days of Future Past” storyline. In that future, Charles Xavier and Cyclops are dead and Magneto, the X-Men’s former archenemy, keeps the X-Men’s hopes alive in a mutant concentration camp in the South Bronx.

It was all prelude to Claremont’s next big revelation, back in the X-Men’s present, in 1980: Magneto, who had never been much more than a megalomaniacal foil before, was not only also Jewish himself, but a survivor of Auschwitz.

“Search throughout my homeland, you will find none who bear my name,” the villain rages, the next time he fights the X-Men. “Mine was a large family and it was slaughtered—without Mercy, without Remorse. So speak not to me of grief, boy. You know not the meaning of the word!” Magneto surrenders, however, when he thinks that he has killed Kitty Pryde, a fellow Jew. Over the rest of the decade, Claremont nudged Magneto’s towards a complete transformation: the Holocaust survivor turned angry villain would become a teacher, the head of the X-Men. It was really very moving.

Storm confronts Magneto, cradling Kitty Pryde in his arms. Panel from Chris Claremont (writer), Bob Wiacek (penciler), and Joe Rubinstein (inker), The Uncanny X-Men Vol. 1, # 150 (Oct., 1981).

It didn’t work. Howe explains how Shooter threw the new “compelling, possibly noble” Magneto under the bus. In Marvel’s new crossover schedule, the villain was no more than a “violent ideologue,” fighting for mutants as a new master race. Jean Grey was resurrected, Cyclops abandoned his new wife and child, and Claremont eventually left Marvel, exhausted. The characters further deteriorated, killing and resurrecting each other in various ways. At one point after September 11th, Magneto killed Jean Grey, ordered his followers to march New Yorkers into extermination chambers, and then was decapitated by Wolverine. Howe suggests that the event’s writer, Grant Morrison meant it as a commentary on Marvel’s absurd cycles of profitable death and re-birth. “Was there any doubt that everyone would come back?”

Of course, one could argue that Marvel’s great theme, and its appeal, is actually ‘resurrection.’ One lovely example is from Mark Waid and Mike Wieringo’s Fantastic Four, in which a teammate has died, and the other three seek him in Heaven. They meet their God, who happens to be Jack Kirby, and return their friend to life. But who rescues someone from Heaven?

It is unclear what any of this mess is a metaphor for, except something supremely non-heroic: the world damages us with holocausts large and small, and when we are given power we are doomed to damage it back, then die, and then come back again. There is no rest.

It’s little coincidence that the very next X-Men movie coming out, in 2014, is borrowing Claremont and Byrne’s “Days of Future Present” storyline. The irony, though, is that instead of trying to avoid a terrible future, the plot—which is being used in the comics, as well—seems to have the X-Men trying to change the present by reaching back to their ‘purer’ selves of the 1960s. The Marvel Universe no longer needs a dystopic future for one of its flagship teams: it can’t imagine anything worse than the one it has today.

VIII. Magneto in Chains

To be fair, Marvel is still making some great comics, and Howe’s book is a love song to the creators that keep them going. This is, in fact, an excellent book, and should be read by Marvel fans and haters alike. It’s a good explanation of how one company can be responsible for so much excitement and beauty, as well as so much loyalty, pain, and penury on the part of its employees.

Ultimately, though, Marvel Comics is an act of great sympathy, making it clear just whose ghosts have been watching readers as they turn the pages and get lost in the panels. Close Pride and Prejudice, and you don’t really have to worry about Jane Austen or your beloved Eliza Bennett any longer. But you do have to worry about Magneto and Spider-Man, and the men and women who have cared for them. As Howe writes,

At a certain point—it’s impossible to locate precisely—decades of continuity exceed the capacity of the human brain. So the Marvel Universe chugs forward, and backtracks, and takes detours. The movie adaptations mix and match from various past interpretations of the Marvel characters, add their own inventions, and, in reaching larger audiences, ultimately supplant the “official” versions of the mythologies. Multiple manifestations of Captain America and Spider-Man and the X-Men float in elastic realities, passed from one temporary custodian to the next, and their heroic journeys are, forever, denied an end.