Local History Excerpt: I Rode with Red Scout: When Yellowstone’s Early Tourists Stumbled into Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce’s Final War

The beginning of some stories rely on the end of others. In 1877, Yellowstone National Park was five years old. It was scarcely organized or maintained, but already it drew a trickle of visitors. This was a West that was not yet “won,” however, and the U.S. Cavalry’s war against the Native Americans was still underway. That summer, nine Yellowstone tourists were entangled in the violence when hundreds of Nez Perce warriors swept through the park, hoping to reach Canada.

Montana native and New York Times journalist Nate Schweber looked into that story as he was researching his book Fly Fishing in Yellowstone National Park An Insider’s Guide to the 50 Best Places (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2012). The book’s chapters each give advice about a lake or stream in the park, interwoven with interviews. The following story is excerpted from Schweber’s chapter on Nez Perce Creek, for which he tracked down historical records—including an unpublished first-hand account of what happened to two of those tourists, the Cowans, in 1877. All direct quotes attributed to George Cowan in the excerpt that follows come from a transcript of the story that George Cowan dictated to his daughter Ethel in April 1920. It’s a reminder of what Yellowstone was before it was a park, and what the U.S. government ended to make it that way.

The junction where Cowan Creek pours into Nez Perce Creek is a peaceful backcountry pool in a meadow deep in grizzly country, where little resident brook trout mingle with occasional big browns that run up from the geyser-fed Firehole River in high summer to escape the heat.

Sallysue C. Hawkins and Otis Halfmoon have both visited these cool waters to better know their family histories, which joined together in the hot summer of 1877 just like the streams. When they were both young they visited Nez Perce Creek with their fathers not in search of fish, like so many visitors do, but rather to better comprehend perhaps the most amazing human drama in the history of Yellowstone National Park.

“It’s an incredible story that has been passed down in my family through the generations,” said Hawkins.

It’s a story that Halfmoon knows the other side of. “I thought of what the Nez Perce went through there in 1877, their suffering,” he said. “And I thought of what the Cowans went through.”

Cowan Creek is named in honor of Hawkins’ great-grandparents Emma Cowan and her husband George, who was shot three times, including once in the head, by members of the Nez Perce tribe, which included Halfmoon’s great-great grandfather Red Owl, and his pregnant great-grandmother, whose traditional name does not translate to English. In this remarkable encounter, which George miraculously survived, Emma was taken captive by the Nez Perce, but was treated with a kindness that she marveled at for the rest of her life. She told stories of the Nez Perce’s hospitality to her daughter Ethel May, who passed them down to her granddaughter, Hawkins.

It all happened along the banks of Nez Perce Creek, which was named in honor of the tribe. The Cowans, from Radersburg, Montana, were among the first tourists in the then five-year-old National Park. That same summer hundreds of Nez Perce—including revered leader and peacemaker Chief Joseph—fled their homeland in Oregon’s Wallowa Valley, and ran from the U.S. Cavalry, on an incredible, bloody, 1,500-mile journey that took them through Yellowstone. Their flight ended in a tragic battle in the Bear Paw mountains in North-central Montana, just shy of the Canadian border.

Hawkins said her grandmother told her that her father, George Cowan, planned the trip to Yellowstone because her mother, Emma, then 24-years-old, had just lost a child and he wanted to distract her from her grief. The trip fell on the Cowans’ second wedding anniversary.

In her own published memoirs, Emma expressed delight at the fishing on the way to the geysers, particularly at the headwaters of the Madison River. She wrote that while camped there on Aug. 14, 1877, “we caught some delicious speckled trout.” They were Westslope cutthroats.

While Emma’s grief was diminishing, the Nez Perce’s was intensifying. For years the tribe had endured as white settlers, wanting more grass for their cattle, encroached on lands in the Wallowa, Snake, and Clearwater Valleys that were promised to the Nez Perce in treaties. As tensions mounted after gold was discovered on Nez Perce land, some tribal members agreed to live on small reservations. In June 1877 several frustrated non-treaty Nez Perce attacked and killed a number of settlers, thus starting the Nez Perce War.

Around 800 Nez Perce made a run for their freedom, hoping to join the Crow Nation in Eastern Montana and live by hunting buffalo, or else escape to Canada to live with Chief Sitting Bull and his Sioux. They were chased by hundreds of soldiers under the command of U.S. Gen. Oliver Howard, who was nicknamed “The Christian General,” for his tendency to make policy decisions based on his fiercely held religious beliefs.

Two weeks before the Nez Perce encountered the Cowans, the tribe suffered a brutal massacre in Montana’s Big Hole Valley at the hands of around 200 U.S. soldiers led by U.S. Col. John Gibbon who—a year after helping identify the deceased at Custer’s Last Stand—gave the order to take no prisoners. The cavalry was augmented with whiskey-fueled civilian volunteers.

Exhausted from their trek, the Nez Perce set up camp, not knowing that Gen. Howard had used a new invention, the telegraph, to inform Col. Gibbon of their whereabouts. The cavalry struck at dawn, ambushing the Nez Perce in their wickups. Author Dee Brown, in his seminal Native American history Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, wrote that 80 Nez Perce were killed, “more than two-thirds of them women and children, their bodies riddled with bullets, their heads smashed by bootheels and gunstocks.”

The Nez Perce who escaped fled with broken hearts and frayed nerves. The survivors followed the Madison River upstream toward its headwaters in Yellowstone at a junction with a river that, five years earlier, had been named in honor of Gibbon.

One of the Nez Perce soldiers killed by Gibbon’s men at the Battle of the Big Hole was Five Wounds, Halfmoon’s paternal great-grandfather. Halfmoon’s parents brought him to the Big Hole Battlefield as a boy and told him family stories. Five Wounds, they said, made a suicide charge at soldiers and was shot from behind. In the early 1990s Halfmoon worked as an interpreter at the Big Hole Battlefield and was there when archaeologists uncovered a 45-70 slug in the exact spot where Five Wounds fell. The bullet was mushroomed, indicating that it had impacted with flesh. Halfmoon believes it was the very shot that felled his forefather.

Five Wounds had gone on the journey with his chiefs having left behind on a reservation his 7-year-old son William, Halfmoon’s paternal grandfather. Halfmoon’s maternal great-great grandfather, Red Owl, and his great-grandmother survived the Big Hole and were then part of a tiny group that escaped to Canada during the final battle. Later, they moved back to America, onto reservation lands.

“By the time they got to Yellowstone, the Nez Perce people were very much hurting,” Halfmoon said. “And a lot of that pain is still there.”

On the afternoon of August 23, 1877, George Cowan met a scout in the Lower Geyser Basin from an army party that included Civil War icon Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, who President Ulysses S. Grant had put in charge of Native American wars. The scout told the Cowans about the Big Hole battle, but promised them that the Nez Perce were not coming to Yellowstone because they were scared of geysers. George was assured that he and his family were, “as safe in the park as we would be in New York City,” he recalled. That night Emma strummed her guitar and sang campfire songs in celebration of the last night of her vacation. She never knew that Nez Perce scouts were listening.

Emma woke George up early the next morning, telling him that she could “hear Indians talking” outside their tent. George dressed quickly and went to meet them carrying his .45 caliber needle gun, then down to its last five cartridges. A young man named Red Scout, a skilled English speaker, told George that he and the men belonged to the Flathead tribe, and were on their way to the buffalo hunting grounds of Eastern Montana. George, an attorney, said that he, “therefore subjected this talking Indian Charlie to what might be termed a rigid cross-examination and at length so cornered him in his statements that he was forced to acknowledge that they were Nez Perce Indians.”

George was soon surrounded by around 200 of them. His temper flared when he saw a member of his party about to dole out flour and sugar to around two dozen Nez Perce hanging around the back of his baggage wagon.

“I immediately ran up using my gun as a sort of club weapon, made the Indians disperse or stand aside,” George said. “If the Indians got any of our supplies they would be taken by force.”

Red Scout took note.

The Cowans tried to flee but a line of mounted Nez Perce halted them at gunpoint. Red Scout informed George that he and his party were to be marched seven miles up the creek, then known as the East Fork of the Firehole River, to see Chief Looking Glass, the leader of his band who Red Scout added was “friendly with the whites.” When the wagons could go no farther, they were ransacked and the group continued on horseback.

In the meadow where Cowan Creek joins Nez Perce Creek, the Cowans met with Chief Looking Glass, Chief Joseph, Chief White Bird and a subchief named Poker Joe, who earned his sobriquet in Montana’s Bitterroot Valley from his love of gambling. Poker Joe, acting as translator, told the Cowans that the chiefs wished to free them, but under one condition. Give the Nez Perce their fresh horses and saddles for fleeing, and their guns and ammunition for hunting buffalo, and they could take with them an equal number of worn out Nez Perce steeds, which would get them back to the white settlements. Under the circumstances, what could the Cowans say?

Poker Joe also warned the Cowans of the limits of the chiefs’ power over some of the distraught Nez Perce warriors. “(He) said that the young warriors having lost many friends and relatives in the Big Hole fight were mad and angry and were hard to keep in control by their chiefs,” George said.

Poker Joe told the Cowans to travel fast through the woods away from the main trail, lest they be spotted again.

The Cowans didn’t heed his warning. After a half-mile of struggling over downed timber and through bogs, they returned to the trail. Almost at once around 75 Nez Perce between the ages of 18 and 25 ambushed them. One was Red Scout, who George noted was, “conspicuous in the command of this party of young Indians.” Red Scout told the Cowans that the tribe had changed its mind about letting them go.

As the gang marched the Cowan party back upstream, two warriors rode ahead—George believed it was to make sure the chiefs were nowhere near—and then came charging back. Emma wrote that, “shots followed and Indian yells and all was confusion.” George took a bullet blast through his left thigh. He saw another Nez Perce aiming a rifle at his head, so he leapt off his horse to avoid being hit. His wounded leg buckled, and he rolled down a knoll and came to rest lying down against a fallen tree.

Red Scout and another Nez Perce man ran to him, but Emma reached her husband first. She threw her body over George to shield him. Red Scout pointed “a large dragoon revolver” at George’s head, but Emma stayed in front of that “immense navy pistol” and “begged the Indian to shoot her first,” though Red Scout “seemed disinclined to harm her,” George said. Red Scout did catch Emma’s right wrist as she tried to cover George, and he lifted her away as she clung to her husband’s neck with her left arm. This pulled George into a partial sitting position and, thus exposed, the other Nez Perce warrior reached into his blanket, drew a revolver, and fired the kill shot. Point blank.

“The ball struck me on the left side of my forehead,” George said. “I saw the smoke issuing from the pistol, and heard the shot, but was rendered unconscious.”

Moments later Poker Joe, sent by Chief Looking Glass and Chief White Bird, rode up to the melee on horseback to halt the violence. Red Scout, who knew he had disobeyed his chiefs, protected Emma and her siblings after George was shot and helped Poker Joe quell the crowd, which included men throwing rocks at George’s bleeding head. A year later Red Scout, who was one of just a few Nez Perce to escape into Canada, spoke to a journalist named Duncan McDonald, whose father was a Scottish fur trader and whose mother was a Nez Perce woman. Red Scout confessed that he had been “in the wrong,” and explained why he safeguarded Emma and her 13-year-old sister Ida.

“I had not the heart to see those women abused,” Red Scout told McDonald, as quoted in an 1878 article in The New North-West, a newspaper in Deer Lodge, Montana. “I thought we had done them enough wrong in killing their relations against the wishes of the chiefs.”

The Nez Perce weren’t finished with George Cowan. He awoke hours later on the opposite side of the downed tree covered in blood, his pockets all turned inside out and emptied. He pulled mightily on a branch to stand upright. Then he turned and saw a lone Nez Perce waiting for him on horseback. The man dismounted, dropped to a knee and fired a single shot that ripped through George’s left hip and came out his abdomen.

“This felled me to the ground again, falling with my face downward,” George said. “I turned my head so that its side rested on the ground and felt the warm blood running from my nose occasioned by its contact with the ground.”

Finally, three bullets later, the Nez Perce left George Cowan for dead.

The Nez Perce took Emma and her sister captive along with their brother Frank, who the tribe hoped could guide them up the creek and across the park. In the Nez Perce camp that night near Mary Mountain, Emma wept on a blanket not far from Chief Joseph. She remembered him being, “somber and silent, foreseeing in his gloomy meditations possibly the unhappy ending of his campaign.” The family story passed down to Hawkins was that the chief was angry with the young men who shot George.

“Chief Joseph wasn’t happy with them for doing that,” Hawkins remembers hearing her grandmother say. “He said, ‘We’re not here to do that, we’re leaving to Canada,’ he didn’t want any more problems with the cavalry and settlers.”

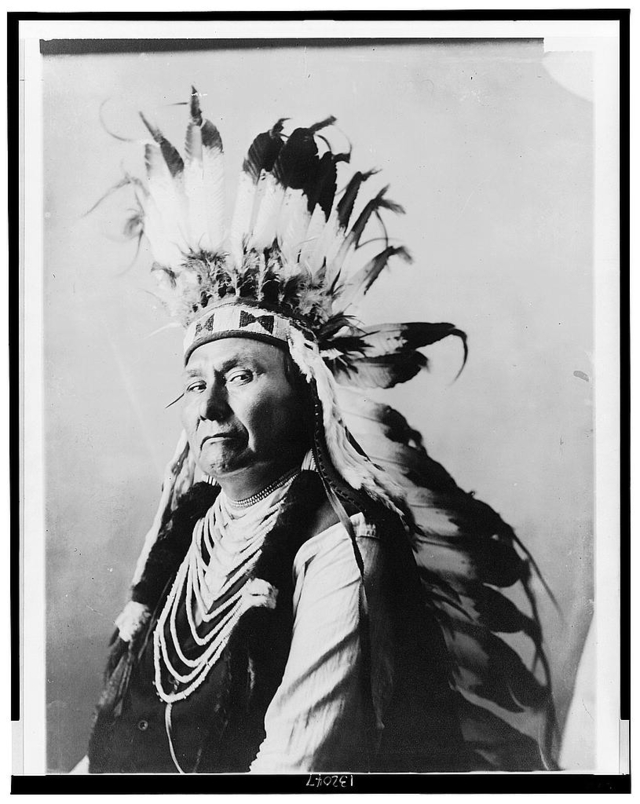

Portrait of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, 1900. Photo by De Lancey Gill; from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog

Hawkins said that Chief Joseph directed a woman in the tribe to give Emma a baby to hold, a gesture meant to cheer her spirit. When Emma took the child she wrote that she saw “the glimmer of a smile,” on Chief Joseph’s face. The infant’s mother asked Emma’s brother, “Why cry?” He said it was because Emma believed that her husband had just been killed. The Nez Perce woman replied, “She heartsick.”

George Cowan, the Rasputin of early Yellowstone, was not dead. A Civil War veteran who was raised on the Wisconsin frontier, he moved to Last Chance Gulch in Helena in 1865 to prospect for gold. A lawyer by trade, he was tapped by Montana Territorial Governor Thomas Meagher in 1867 to lead soldiers to fight Native Americans. By the banks of Nez Perce Creek, George crawled on his elbows into a willow thicket, and then managed to cross the stream. It took him four days to crawl ten miles back to his camp in the Lower Geyser Basin. There, two of Gen. Howard’s’ army scouts discovered him. Their first words were, “Who the hell are you?” When George answered they replied, “Why, we expected to bury you.”

In a diary of the Nez Perce War Army scout William Connolly noted that on August 30, 1877 he, “found a wounded man shot 3 times by the Nez Perce Indians.” The other scout was reportedly Col. J. W. Redington. The army men attempted to comfort poor George by building him a campfire. That night the campfire spread into a small forest fire that nearly killed him again.

“I crawled through this fire for perhaps thirty yards until I got clear of it,” George said. “Burning both my hands and knees in so doing.”

Emma woke the morning after her capture to find a Nez Perce woman trying to keep her warm by rebuilding the campfire by her side. The woman, “then came and spread a piece of canvas across my shoulders to keep off the dampness,” Emma wrote. Her sister Ida slept nearby on buffalo robes prepared by Nez Perce women, who also gave her bread and brewed her tea made from willow bark. The Nez Perce women slept surrounding their frightened charge in order to keep her safe.

The tribe continued east, crossing the Yellowstone River at what is now Nez Perce Ford. On the far side, Nez Perce women offered Emma a lunch of Yellowstone cutthroat trout, giving a clue as to what the tribe ate on part of their journey. Emma declined. She wrote, “From a great string of fish the largest were selected, cut in two, dumped into an immense camp-kettle filled with water and boiled to a pulp. The formality of cleaning had not entered into the formula. While I admit that tastes differ, I prefer having them dressed.”

Poker Joe again released Emma and her siblings and this time he rode with them back across the Yellowstone River and a half-mile downstream until they were well along the trail. He had given Emma and her family their bedding, a waterproof tarp, bread, matches, two old horses and a jacket for young Ida. The chief shook their hands and said, “Ride all night. All day. No sleep.”

This time, they took his advice.

George and Emma were reunited days later at the Bottler’s Ranch, home of early settlers in the Paradise Valley south of Livingston, Montana. On the way home their story turned slapstick. Seven miles from Bozeman, George and Emma’s two-seat wagon flipped over and tossed them out before careening down an embankment and coming to rest upside down in some pine trees above a river. Then in Bozeman, as George rested in a hotel bed, his doctor sat down beside him and collapsed the bedframe. George went sprawling out on the floor and there suggested that someone use artillery on him, since nothing else could finish him off.

Hawkins said that her grandmother was always proud of the fact that her father lived. He was too.

“He was lucky to survive and he knew it,” Hawkins said. “He was also pretty tough.”

Later in his life George confessed to his daughter Ethel that perhaps his well-known bluntness might have escalated the situation, particularly with regard to Red Scout.

“I think my great grandfather realized he could’ve handed it a little more diplomatically,” Hawkins said. “It’s one of those incidents where hot headedness prevailed, both with the young Indians and my great grandfather.”

George Cowan was headstrong, literally. From 1877 on he carried around a watch fob made from the bullet that a field surgeon cut out of his skull. The slug was mushroomed from its impact with flesh. The fob is still a family heirloom.

“That’s where we get our hard-headedness,” Hawkins said.

George and Emma moved from Radersburg to Boulder, Montana in 1885, then to Spokane in 1910. He visited the park three more times in his life, always going back to revisit the spots where he was so tested. He passed away in 1927 and Emma followed in 1939. Theirs was, by all accounts, a happy ending.

The Nez Perce story, by contrast, ended in sorrow. By October, the beleaguered tribe made it within 40 miles of the Canadian border, so close that many thought they were safe. Unfortunately, as with the Battle of the Big Hole, the Nez Perce could not outrun the telegraph. A message went out, and U.S. Gen. Nelson A. Miles attacked the Nez Perce at the foothills of the Bear Paw Mountains.

The awful, final battle lasted for five days. Poker Joe was killed. Chief Looking Glass too. Only a few, including Chief White Bird, Red Scout and Halfmoon’s surviving relatives, snuck to Canada under cover of darkness. Chief Joseph surrendered to Gen. Howard, who had finally caught up and promised that upon surrender the 500 remaining Nez Perce would be taken back to their reservation in Lapwai, Idaho. Under those conditions, Chief Joseph agreed. There the heartsick chief made his immortal speech saying, “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

That winter, Gen. Sherman broke Gen. Howard’s promise and ordered the Nez Perce penned and shipped on unheated rail cars to a prisoner of war camp in Kansas, then later to a reservation in Oklahoma where many died of disease. For years Chief Joseph pleaded with leaders in Washington D.C. for his people to be returned to their homeland. Finally, in 1885 some of the Nez Perce were allowed to return to the reservation in Idaho, but Chief Joseph was still considered too dangerous to join them. He was exiled to the Colville Reservation in north-central Washington where he died in 1904. His doctor said the cause of death was “a broken heart.”

In the few years after the Nez Perce’s run through Yellowstone, in which two other unlucky tourists were killed and others wounded, park superintendent P. W. Norris evicted the Sheepeaters, the only Native Americans to call the Yellowstone region their year-round home. Though the Sheepeaters played no role in the Nez Perce War, Norris feared their presence would deter tourists from visiting.

When Halfmoon visited Nez Perce Creek, he had a revelation about his tribe’s journey. The Nez Perce had made incredible time running from Gen. Howard, even traveling uphill through thick timber over the rugged Bitterroot Mountains with women, children, their injured, wickups, and hundreds of head of livestock. In Yellowstone though, their pace slowed. Some historians said it was because they didn’t know their way. Halfmoon thinks it was something else.

“I saw the trees and I felt the cool air in Yellowstone Park and it reminded me of the Wallowa Valley,” he said. “I realized that it must’ve been at this point that these people became very homesick, realizing that they would never see the trees or feel the air of their home again, and they realized by then that if they were caught they would be slaughtered. These feelings slowed them down.”

Stereogram from Gardiner’s River Series, Yellowstone National Park, published 1876. Photo by Joshua Crissman; from Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog

Reflecting in her memoir on the treatment she received at the hands of the Nez Perce, Emma wrote, “knowing something of the circumstances that led to the final outbreak and uprising of these Indians, I wonder that any of us were spared.” In perhaps an unwitting nod to the Nez Perce’s pursuer, “Christian” Gen. Howard, Emma added, “Truly a quality of mercy was shown us during our captivity that a Christian might emulate.”

That message was passed down in family lore.

“My grandmother always told me that my great-grandmother and great-grandfather never harbored any animosity toward the Nez Perce,” Hawkins said. “They understood later what the Nez Perce were going through, that they were being driven from their homes.”

The story of the Cowan family and the Nez Perce goes on. Halfmoon is a National Park Ranger who worked for years at the Bear Paw Battlefield and is an expert on the Nez Perce War of 1877. He had searched for years for descendants of George and Emma Cowan. When contacted for this book, he called back within minutes.

“You found Cowans, eh?” he said.

Halfmoon explained that beginning in 1977, the centennial of the war, the Nez Perce began an annual powwow on their reservation in Lapwai. The tribe has made it a tradition at the Chief Joseph and the Warriors Powwow to honor descendants of the cavalry who chased the Nez Perce. It is to recognize their shared history, Halfmoon said.

He extended the same welcome to the Cowan descendants.

“We would like to honor them,” he said.

Thus a June 2011 email that I sent from New York City addressed to Hawkins, her cousin Sharon Strand, and Halfmoon marked the first time there was contact between the Cowan family and the Nez Perce tribe since their ancestors met so fatefully in Yellowstone Park almost 134 years earlier. Halfmoon called Strand on the telephone and invited her and her family to the Chief Joseph and the Warriors Powwow. The timing didn’t work out (when I finally tracked down Halfmoon, it was less than a week until the powwow) but the two had a friendly chat and were making plans to one day meet each other.

The Nez Perce Creek that the Cowans and the tribe encountered on their historic Yellowstone visit had no fish, as it sat above an impassible falls on the Firehole River. In 1890 Nez Perce Creek became the first stream in Yellowstone to be stocked with Von Behr brown trout, a species of fish that originally hails from Germany. These trout flushed up and down the watershed and, in the next few decades, were bolstered by additional brown, rainbow, and brook trout stocked throughout the Firehole, Gibbon and Madison River systems. The result was that by the time Emma Cowan died in 1939 these rivers were all great sportfisheries, but their native Westslope cutthroat trout, which she delighted in catching and eating in the days before her capture, were either exterminated, hybridized or pushed into just a few tiny, inhospitable headwater streams where no other trout lived. It’s hard not to see Nez Perce Creek trout as a metaphor for European settlement of North America, with regard to native people.

As my book was about fishing, I had to ask both Hawkins and Halfmoon if on their visits to Nez Perce Creek they ever wet a line. No, they said.

I asked the same question to Stan Hogatt, a tribal historian.

“Out of all my Nez Perce acquaintances I don’t know anyone who has ever fished there,” he said.

“That would be the furthest thing from their minds when they are visiting those sites.”