Why Did J.P. Morgan’s Prize Bulldog Die of Shame?

Sometime during the second week of July 1898, as American troops waded ashore in eastern Cuba and U.S. warships encircled the Spanish-held Philippines, a smaller conflict raged at the financier J.P. Morgan’s summer estate on the banks of the Hudson River in Highland Falls. The New York Times noted:

A battle almost to the death was fought yesterday morning between J. Pierpont Morgan’s prize bulldog and a Maltese cat belonging to Mrs. Charles F. Tracy. When the fight ended the bulldog had lost one eye, the other optic was badly damaged, and his nice sleek hide was furrowed and ridged with innumerable scratches from which rich prize blood flowed in profusion.

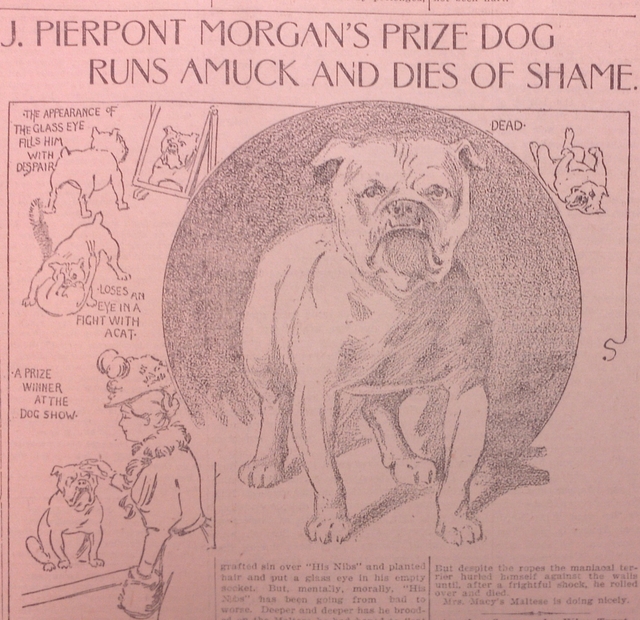

The Morgans brought the beaten combatant, “His Nibs,” to a New York dog hospital, but after the bulldog went mad and died, the New York World declared him a “suicide.” Joseph Pulitzer’s ‘yellow’ newspaper lived for sensationalist class-war stories like this. Their cartoon illustrated the story with a five-part narrative of the dog’s disgrace. In this account, His Nibs’s dog-show glories are followed by the fight with Mrs. Tracy’s cat. After losing the eye, he is fitted for a replacement, but when he sees his reflection in a mirror, the caption explains, “the appearance of the glass eye fills him with despair.” The cartoon concludes with an image of the dog belly-up, with the superfluous, maybe triumphant caption, “dead.” In a bitter muckraking recounting of the episode, J.C. Cooper quoted from the New York News Dispatch: “The corpse of the dog lay in a casket lined with silk.” Cooper adds that a few days earlier, a U.S. soldier’s newborn baby had died, freezing, in a Denver slum.

His Nibs combines three conventions of 1890s culture: the class politics of masculinity, pet ownership, and suicide. The first is a well-trod subject of 1890s history. The decade that saw the founding of the YMCA, professional sports, and America’s overseas empire is often remembered as the decade of “the strenuous life,” Theodore Roosevelt’s nostalgic ideal of a vigorous republic based on hard labor, martial valor, and virile conflict. It is also the decade of neurasthenia, the term for nervous disorders thought to afflict women and over-cultivated men alienated from virtuous labor, and a reputed rise in human suicides. The 1890s, the so-called “Gilded Age,” was also period of intense class conflict, manifested in strikes and mass demonstrations. At the same time, the 1890s saw an increase in pet ownership, as both a middle-class trend and an aristocratic hobby. As they still do, dog lovers in the nineteenth century projected human feelings as well as political symbolism onto their mute companions. Class critiques of plutocrats like Morgan were channeled through the macho cultural politics of pet ownership, in which the financier’s moral weakness is comically betrayed by his seemingly tough bulldog’s wimpiness. In other words: while J.P. Morgan lacked the good sense to die of shame, at least his dog didn’t.

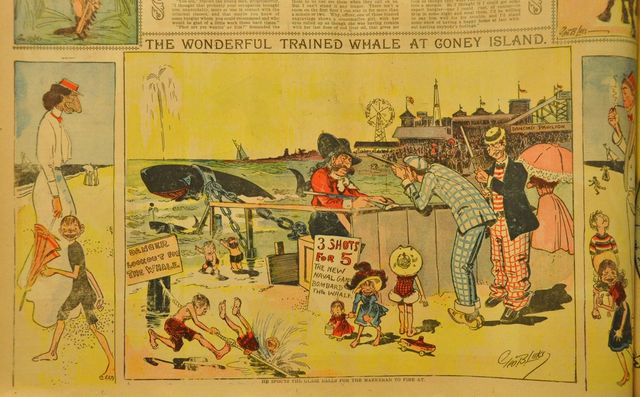

“The Wonderful Trained Whale at Coney Island” (New York World, August 14, 1898, Comic Weekly Supplement, 4).

The daily papers show how the Spanish-American War was in many respects a pinnacle of this popular identification between virtue and virility, benevolence and empire. The New York World in those months was full of everyday tales of animal violence, both self- and human-inflicted. Dominating animals showed, on the one hand, the strength to restrain and make use of the natural world. At the same time, men’s relationship with animals also proved their civilized humanity. Take, for example, a World’s cartoon that satirizes both animal cruelty and the war fever by imagining a new Coney Island amusement: a “new naval game” that allows beachgoers to imitate the victorious U.S. Navy fleet by taking potshots at a not-so-fearsome trained whale. In the same issue, just above two news stories from the warfront—and an editorial by Mrs. Jefferson Davis entitled “What Part of a Husband’s Income Belongs to His Wife?”—was an article about a fight to the death between two male alligators at the Central Park menagerie. “No two bulldogs ever fought with more savageness” than these “lusty” creatures of the tropics, who are described in the article as fighting with as much energy as “Spaniards dodging American cannon balls.” In these sensational stories, animals are wild, but under civilized control, as the Spanish soon will be in Cuba. The alligator “cannibals” in the zoo recall a “savage” manhood whose “lusty” instincts were unrestrained by marriage or any other modern institution.

Dogs, of course, were different: according to the papers, they could kill themselves, as well as other things. In 1858, Holmfirth, “a fine, handsome, and valuable black dog of the Newfoundland species,” apparently drowned himself in a pond. “The case is worth noting,” wrote Edward Jesse in an article that year, “as affording another proof of the general instinct and sagacity of the canine race.” Canine suicides were evidence of what dog lovers most value in their pets—their seemingly human sympathy and subjectivity. Dying of shame, as His Nibs allegedly did, proved the same point, that dogs were capable of such refined emotions.

Dog suicides in 1898 were always male. The suicides were usually expressions of a fragile emotional state. Like Nibs, their humiliation was provoked by a neglectful family, an unkind mob, or by abuse from boys, women, or cats. Sarah Knowles Bolton, in the 1902 book Our Devoted Friend, The Dog, devoted an entire chapter to dog suicides. For example: Rex, a prize-winning Gordon Setter, was worth $300 and drowned himself after he was kicked on the head by a private watchman. Most suicidal dogs were pure-bred, which presumably led to their emotional fragility: a $10,000 dog in Boston deliberately drowned himself, writes Bolton, after he was devastated by an insult from a thoughtless kennel-keeper.

Still, it wasn’t only the effete dogs of the elite who committed suicide, their fragile, puffed-up pride wounded by some slight. Plebeian dogs had the character and sensitivity that their social betters sometimes lacked, and when it was offended, they responded with despair. For example, Bolton records “a stag hound” pursued into the Bowery by a gang of street children until he threw himself under a streetcar in despair. Nero, another Newfoundland, from New Jersey, was “buried with honors,” according to The World’s headline. Nero was a purebred dog with a working-class lineage. Despite his imperious name, he was the dog of Frank Hall, a railroad coal man, and a creature well known to the train engineers, who, the article reports, he would greet by running alongside the tracks. Nero was a cheerful dog, until Hall whipped him for tearing his daughter’s dress. After that, “the way he shunned the society of his little mistress and her companions; his silence and abstraction and loss of appetite, were all direct and irrefragable evidence of the deadly purpose that was forming in the canine mind.” He committed suicide by throwing himself in front of a train (after drowning, this seems to have been the most popular method). The engineers who witnessed his death recalled Nero with tender affection. “It was as plain a case of suicide as you ever heard of,” said the driver of the offending train in The World. “I felt just as bad as if I had struck a man. It took all the nerve out of me.”

His Nibs, however, was an appealing target for a paper like The World because coverage of his death could subtly mock his wealthy master. The World styled itself as an advocacy paper given to sensational dramas and popular crusades—the “liberation” of Cuba by U.S. invasion is the most famous of these. Exposing the scandalous excesses of New York’s elite was one of its regular features (as was praising the elegance and philanthropic generosity of the same). His Nibs offered the World a golden opportunity to combine animal violence and class conflict in one melodramatic package. For one, His Nibs—a mock aristocratic title given to a self-important person—was supposedly named by Morgan’s servants, who were responsible for looking after their boss’s pet. Add to this the fact that His Nibs was also a bulldog, a breed with a resolutely masculine name that manages, in its appearance, to channel both the confident aggression of male youth and the ineffectual droopiness of masculine old age. That such a dog, pampered by servants, should die at the hands of a woman’s thoroughbred cat and his own wounded vanity, was gravy—and an easy way to mock Morgan’s excesses too.

If His Nibs revealed something about his master’s vanity, this was because of the moral significance that Americans began to attach to their domestic animals at the turn of the century. Morgan’s squat, preening bulldog is a perfect example of what Thorsten Veblen, in his classic Theory of the Leisure Class, called the “canine monstrosities” of fancy-bred dogs, whose aesthetic value is in direct proportion to their practical uselessness and cultivated grotesqueness. Yet as Jennifer Mason, in her Civilized Creatures: Urban Animals, Sentimental Culture, and American Literature, points out, prize dogs like His Nibs made up only a portion of the U.S. pet population, which sharply increased in this era. It was the Neros and Bowery stags on whom most dog-lovers showered their affection. “To the minds of many in this period,” Mason writes, “the success of an urban and suburban society depended less on periodic exposure to wilderness and untamed nature than it did on the proper care and keeping, within the built environment, of animals who participated in civilization.” Sympathy for animals, especially those who depended upon you and did nothing economically valuable in return, was a reliable indicator of your character, a point hammered home repeatedly in Our Devoted Friend, the Dog. Hence the paradox of naming animal welfare organizations “humane societies,” many of which were founded in the 1880s and 1890s: the way in which one treated animals was a reliable indicator of one’s sympathy for fellow humans. For this reason, suicidal dogs stood in judgment of the society that drove them into its lakes and rivers and under its streetcars and locomotives.

Ironically, the exact opposite was often true, as the American concern for animal welfare could serve as a smokescreen for an author’s relative indifference to human welfare. For example, nineteenth-century travel writing by Americans in Latin America is full of high-minded denunciations of bullfighting and cock-fighting. Abbie Brooks, a Floridian who wrote under the pen name Sylvia Sunshine, visited Cuba when slavery was still legal and published a travelogue called Petals Plucked from Sunny Climes (1880). It is stunning to read the account of a cock fight on a sugar plantation in Matanzas, in which she complains only about the “disgraceful” treatment of the chickens. On the very same page, she writes dispassionately that enslaved children nearby “receive about the same attention as puppies—upon which they thrive very well.”

The public outrage over the $12 million inheritance that the real estate magnate Leona Helmsley recently left to her fluffy lapdog, Trouble, now seems like nothing new. The gender dynamic from His Nibs’ humiliation by a cat—where a man’s moral and physical weakness run parallel—now finds expression in the public’s fascination and disgust with the toy dogs of wealthy, idle women, like Helmsley’s Trouble and Paris Hilton’s Chihuahua, Tinkerbell, who, like His Nibs in 1898, live better than many of our fellow citizens. Like Morgan’s bulldog, Trouble has a staff on her master’s payroll: the general manager of one of Helmsley’s hotels looked after the dog, although the Times notes that he altered her diet of crab cakes and cream cheese to canned dog food once Helmsley passed away. When the dog died last year, the New York Times called her “the world’s most hated Maltese.”

Unlike His Nibs, however, Helmsley’s dog died of old age. The 1890s are back—but Trouble, apparently, was never even ashamed.