Whose Apocalypse? A New Mercantile Meaning of the “The End” in the New World circa 1600

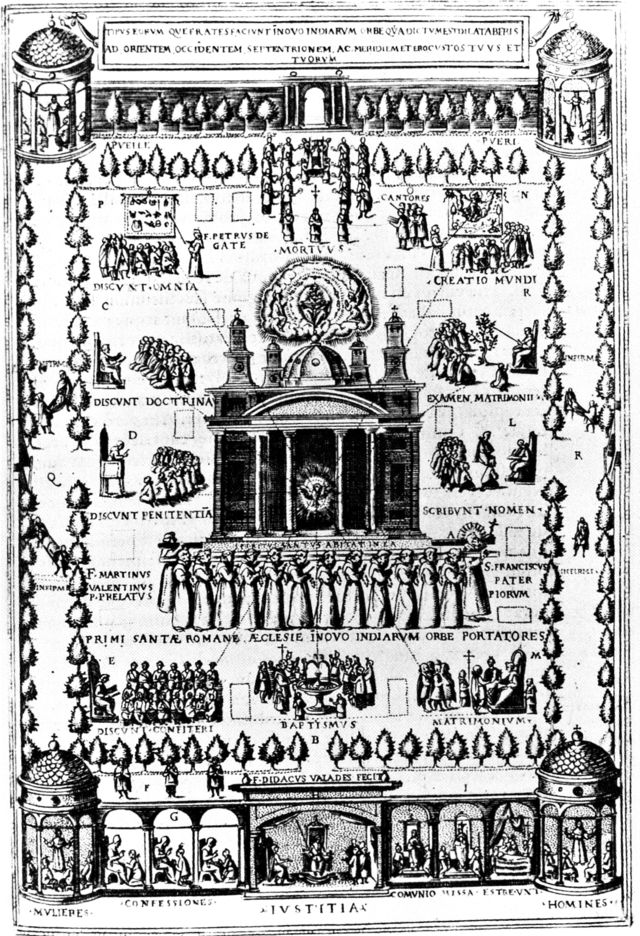

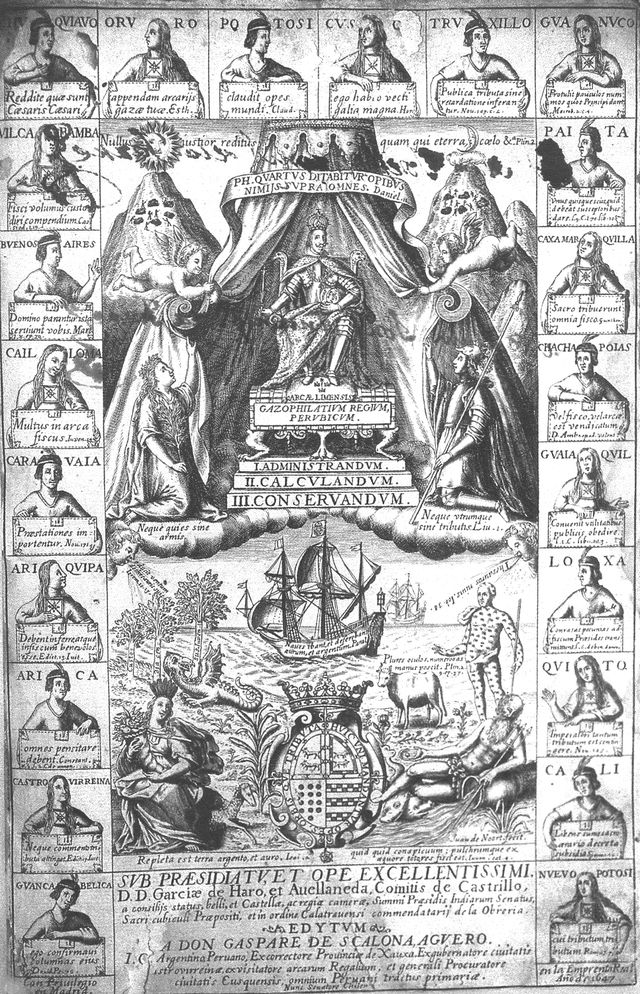

It is hard to imagine two images more different than these. The first appeared in Rhetorica Christiana, a book published in Perugia in 1579 by Diego Valades, a Mexican friar of Spanish and indigenous descent—a mestizo. The second appeared in Gazophilatium regium Perubicum, a book published in Madrid in 1647 by Gaspar de Escalona Aguero, a high-ranking magistrate from Lima, Peru’s capital, which was then under Spanish rule. Rhetorica’s image described an idealized Franciscan missionary compound in the central Valley of Mexico. Gazophilatium depicted the contributors and beneficiaries of the system of taxation in the Andes, from Popayan to Buenos Aires. And yet, for all their differences, both images outlined conditions that could lead to the end of the world.

The first image, from Valdes’s book, depicts twelve Franciscans, Martin Valencia (the head of the Mexican apostles), and St. Francis himself carrying the newly created Mexican church on their shoulders. They are surrounded by a quaint, walled compound where Indians of both sexes receive the sacraments, from baptism to communion to confession to marriage to last rites. The friars, meanwhile, teach their charges using images, Aztec hieroglyphs, and local flora as texts. The key to understanding this image is the Holy Spirit that dwells within the church on the Franciscan apostles’ shoulders. The Holy Spirit descends from a celestial court presided over by the other two members of the Trinity.

That descent of the Holy Spirit reflected the ideas of Joachim of Fiore, a twelfth-century Calabrian abbot who numbers among the most influential Christian philosophers of all time. Fiore thought that contemporary events were recapitulations of past ones. The key to understanding time was figuring out how the Old Testament prefigured the history of Christianity, from Christ to the present. Fiore divided the Old Testament into seven periods, from Adam to Noah to Abraham to Moses to David to the destruction of the temple to Christ. The history of the Christian church recapitulated these periods, with parallel heroes, wars, tragedies, and rewards. Present events were fulfillments of Old Testament ones. By using the Old Testament as a guide, Christians could make predictions—the foundation of medieval and early-modern European prophecy.

Fiore added complexity to his model by reading history through the perspective of the Christian Trinity. If the Law of the Father and the Charity of the Son had first dominated the past, the Holy Spirit would rule the future. The third age would have thoroughly spiritualized humans: meek and humble men as laity and mendicant friars as clergy. There would no longer be need for ecclesiastical hierarchies—including popes.

The Franciscans who led the spiritual “conquest” of New Spain when they arrived in 1524 thought they were stepping into Fiore’s new third Spiritual Age: the twelve friars were prefigured by the apostles of earlier Christianity; the Mexican natives were allegedly humble, pious and docile; and the new church they were building made no room for salaries, ecclesiastical rents, and hierarchies. Mexico was literally a New World on the eve of the millennium.

For a time, the Franciscan vision of the New World found adherents at the highest levels of Spanish power. After lengthy theological-political debates at universities, councils, and the court in the 1540s, King Charles V wholeheartedly committed himself to honoring the Pope’s 1492 delegation of the Holy See’s spiritual sovereignty over the Indies to the Spanish monarchy. As interpreted by the famous Indian defender Bartolomé de las Casas, the only right the Pope gave the monarchy in the Indies was to spread Christianity; the crown could neither topple rightfully constituted Indian rulers nor appropriate lands and resources that belonged to them. Duly chastened by Las Casas’s vision, Charles V awarded most authority to the Franciscans in Mexico while curtailing the power of encomenderos and conquistadors. He told his viceroys to subordinate all temporal power to the church’s spiritual sovereignty.

That Franciscan understanding of the apocalypse in the New World did not last long, however. By 1568, the Spanish crown had reconsidered its commitment to the church the Franciscans had built in the New World. Philip II, the son of Charles V, decided that his father’s Lascasian vision was untenable with so many new military fronts opening up in Europe, Africa, and India: Ottomans, North African Berber pirates, English Anglicans, Dutch Calvinists, and French Huguenots. Moreover, the New World seemed to be spinning out of control. Cantankerous encomenderos and conquistadors were planning and executing rebellions. Worst of all, the pope was reconsidering the Spanish monarchy’s spiritual sovereignty over the Indies. He planned to send a delegate, a nuncio, to rule over the new church in America. Philip II decided he needed to radically change the empire’s course: the church’s pursuit of spiritual sovereignty in the Indies had to be subordinated to the geopolitical goals of the Spanish universal monarchy, not the other way around.

In 1568 the king convened a national junta of powerful councilors and bishops that would shelve his dead father’s Lascasian dreams and ended Franciscan hegemony over the Mexican church and polity. All debates over Spain’s right to the Indies abruptly ended: the Junta established that the crown had political authority over the Indians and, more importantly, dominium over the Indians’ labor and possessions. The Junta also laid out the rules for a new economy in which mining and forced labor would dominate all economic pursuits. Under the Junta’s guidance, an unprecedented mining boom began in Potosi, today part of Bolivia, and the New World church would expand with parish priests, cathedral cabildos, and bishops, precisely the type of ecclesiastical hierarchies Franciscans had sought to eliminate.

Yet the Junta did not give up the Joachomite theology that had inspired the Franciscans. A new age was dawning, indeed, but it was one in which the Indians would contribute as laborers, producing the silver needed to rebuild Jerusalem.

Our second image, from Gaspar Aguero’s book, Gazophilatium regium Perubicum, details how the Junta’s new apocalyptic sensibilities, founded on wealth and souls, played out in Peru decades later. It depicts Philip IV, the grandson of Philip II, sitting on the ark of the Peruvian treasury. It suggests a sacred king dwelling in the Temple’s tabernacle, whose curtains are held by cherubs. Biblical references present the Hapsburgs as the fourth monarchy of the book of Daniel. The mines of Potosi looming in the background, and the twenty-two indigenous tributary regions surrounding the king, will fund Philip IV’s fourth millenarian monarchy. Beneath the king’s feet, fleets cross the ocean: they are the Old Testament Israelite fleets that went to the faraway island and lands of Tarsis and Ophir that allowed Solomon, the monarch of Judah and Israel, to build the Temple. For Aguero, Peru and its mine Potosi are the new Tarsis and Ophir, making the universal monarchy of Philip IV possible.

In sum, the image argued that Philip IV was destined to rebuild the temple of Jerusalem at the end of time. But it also revealed that there is such a thing as mercantile millenarianism: the dream of perpetual peace achieved by resource extraction, better banking, and economies of scale. Philip IV’s perpetual peace came at an extraordinarily high cost: it brought all spirited debates over the ethics of empire and colonialism to an abrupt end.

We are heirs to this triumph of political pragmatism and geopolitics. We have embarked on a mercantile millenarianism of our own—one that allegedly yields perpetual peace by building ever larger shopping malls.