Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb

Jonathan Fetter-Vorm grew up hearing strange stories about his grandparents’ work during World War II: vats of radioactive water, neighbors disappearing in the middle of the night. Only years later, after Fetter-Vorm had graduated from college with a B.A. in history and apprenticed as a letterpress printer and hand-bookbinder, did he understand how his grandfather could have been a welder at the Hanford Site in Washington, the location of the first industrial-scale plutonium reactor, without any idea of what he was working on. The neighbors who disappeared in the middle of the night turned out to have talked too openly about their work for what was, of course, the Manhattan Project—the momentous, accelerated U.S. war effort to beat the Germans to an atomic bomb.

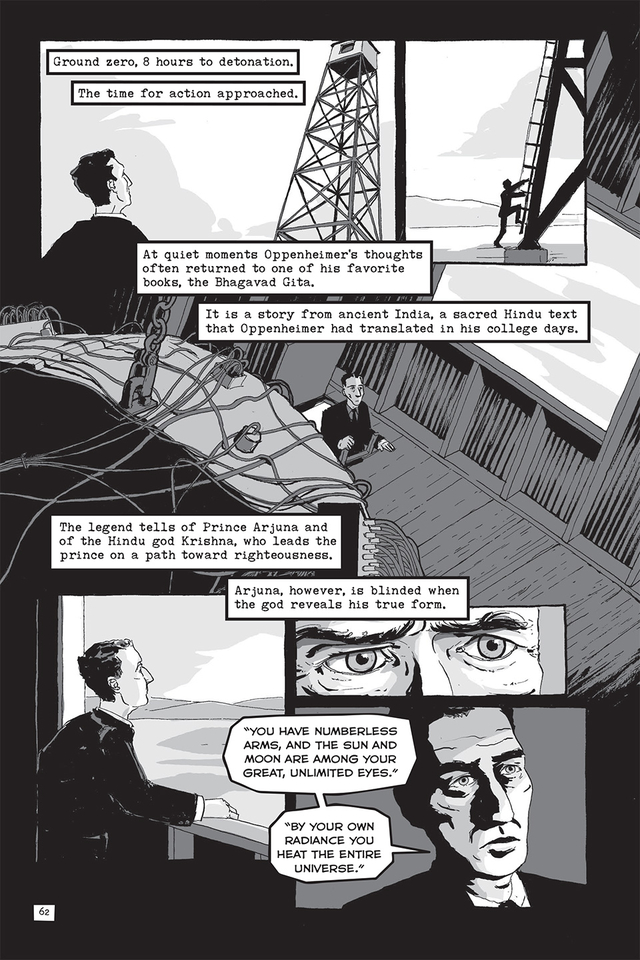

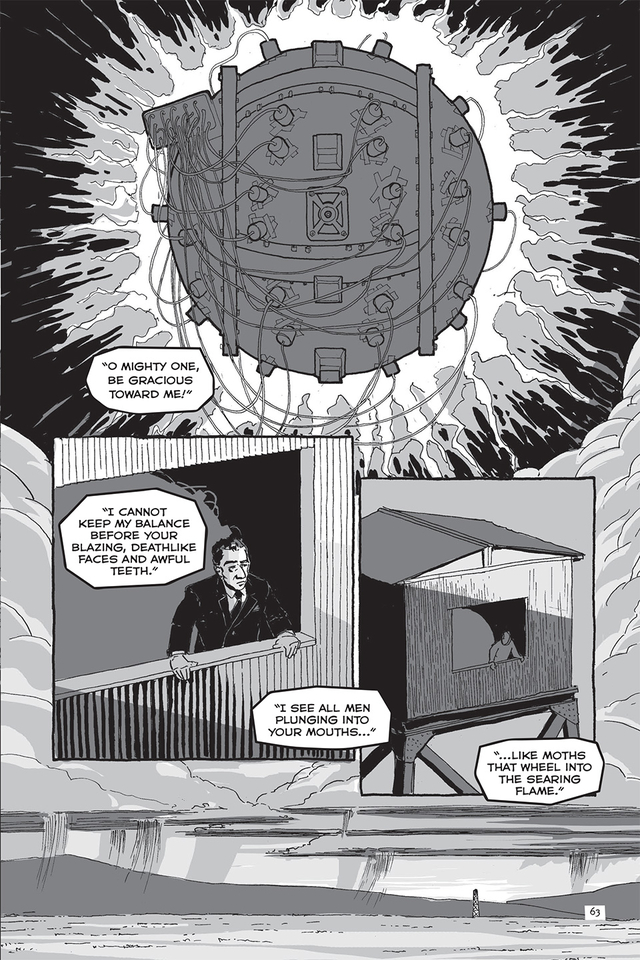

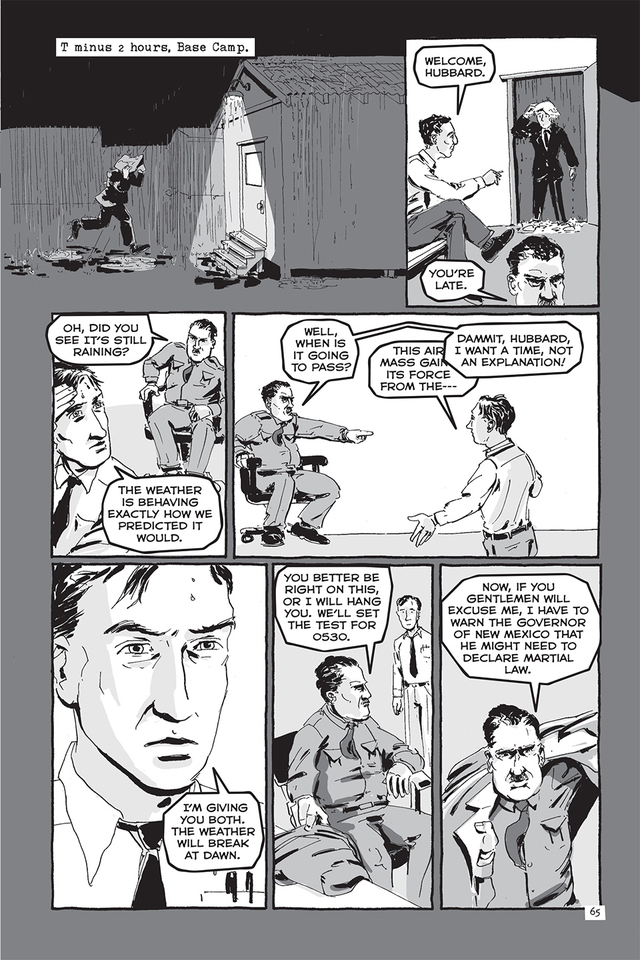

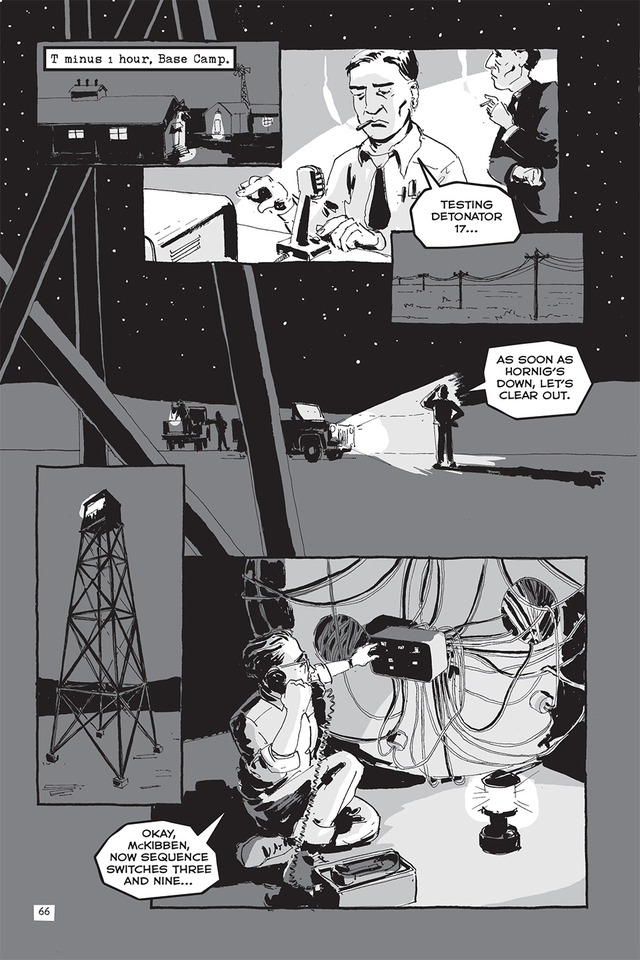

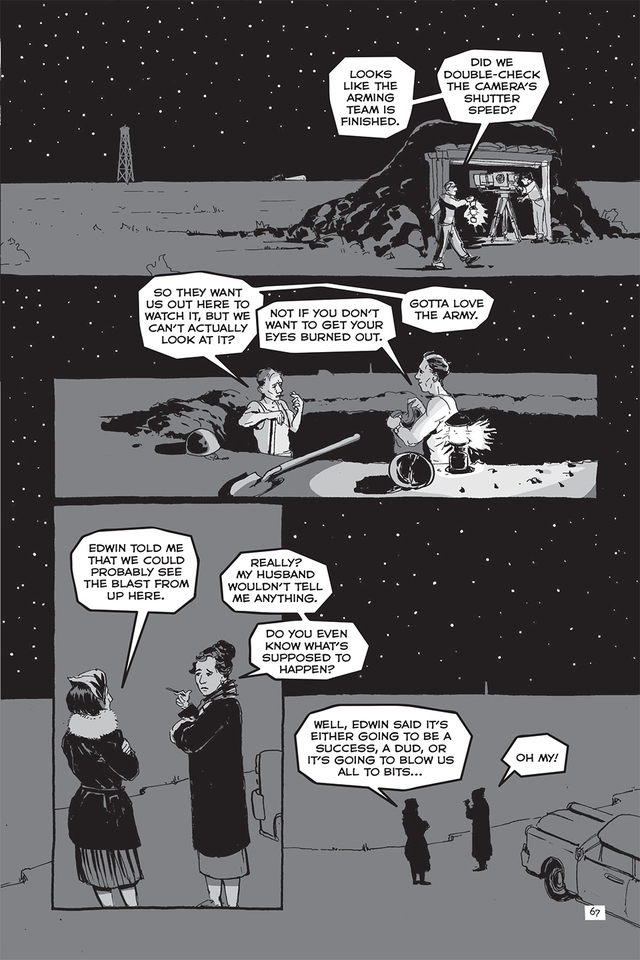

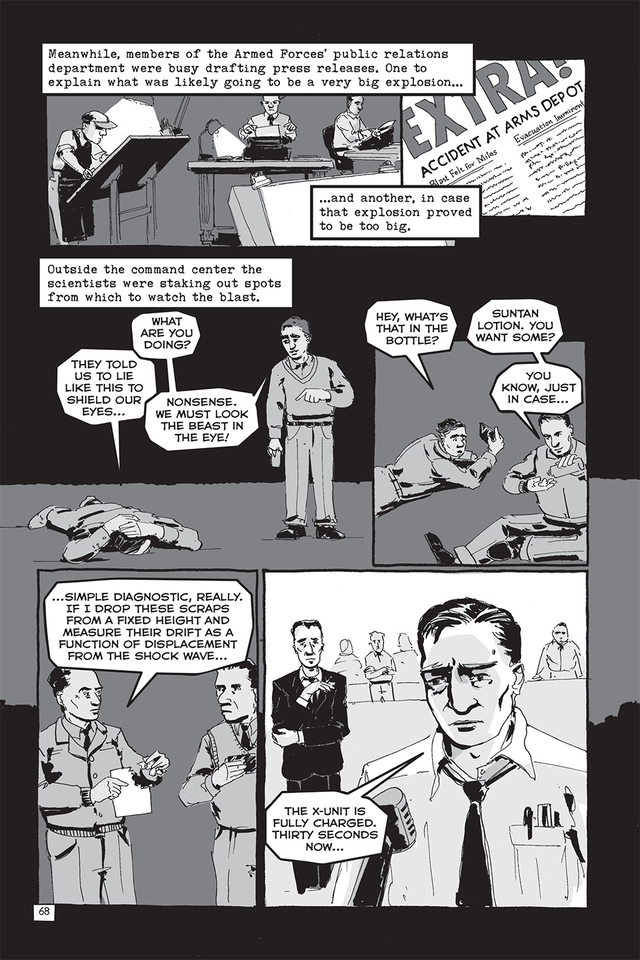

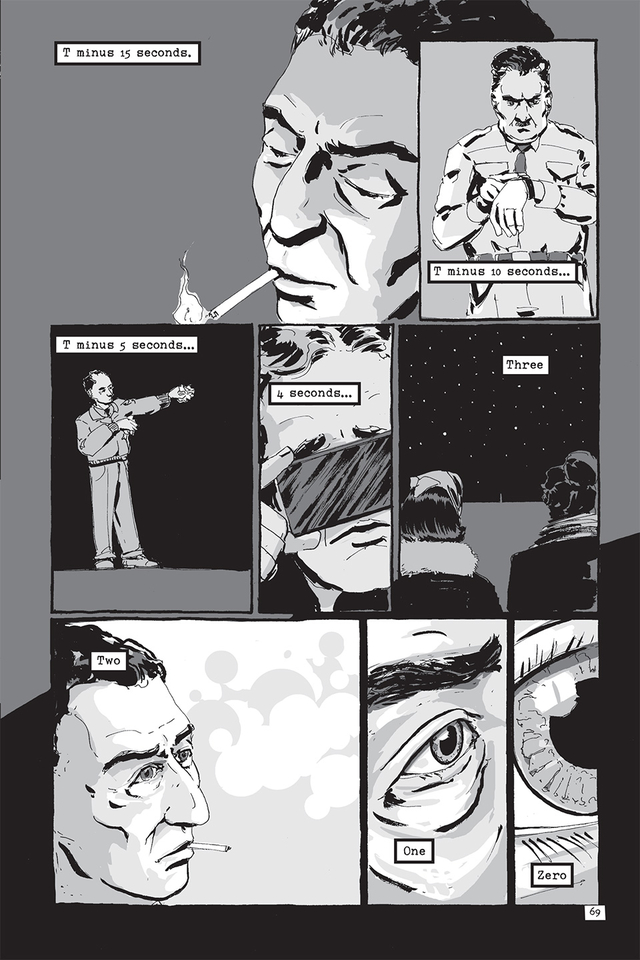

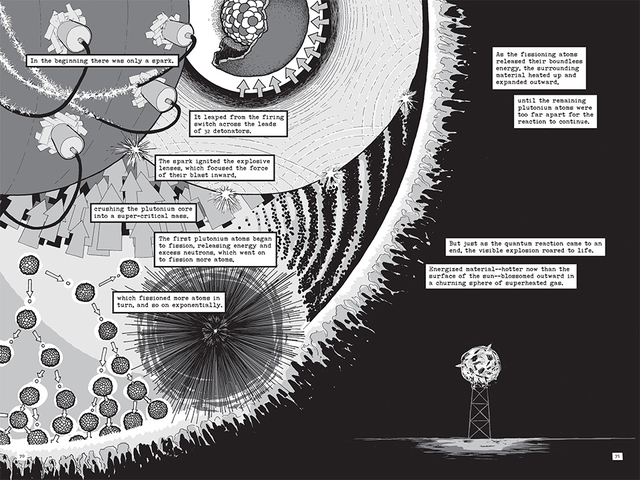

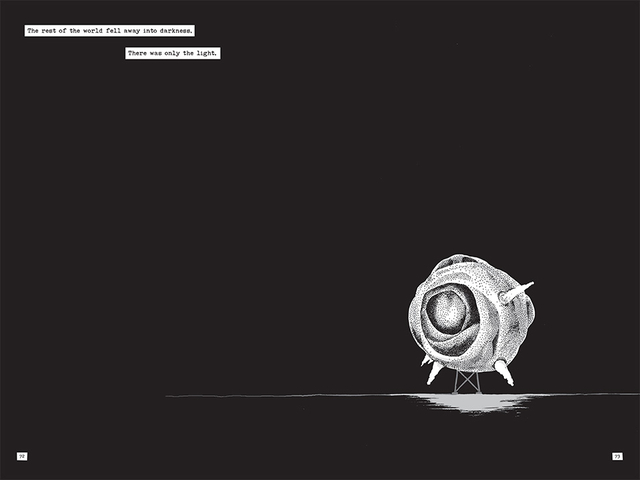

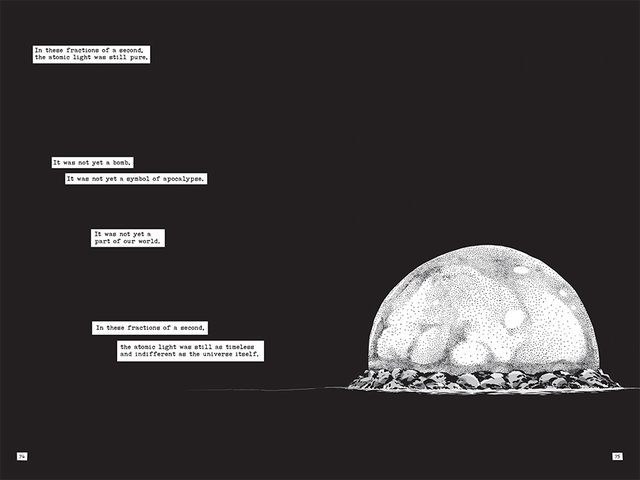

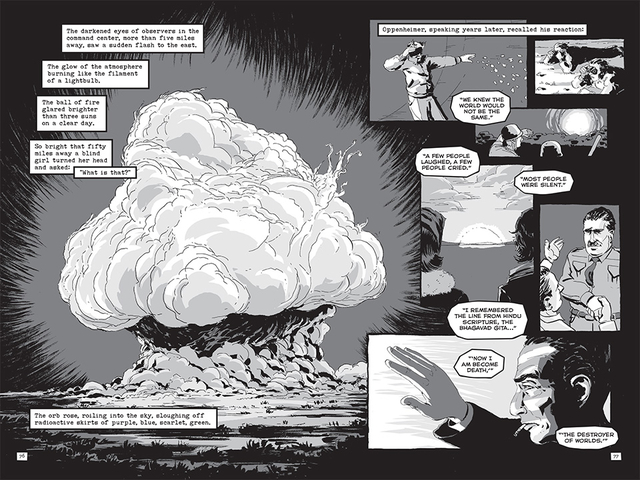

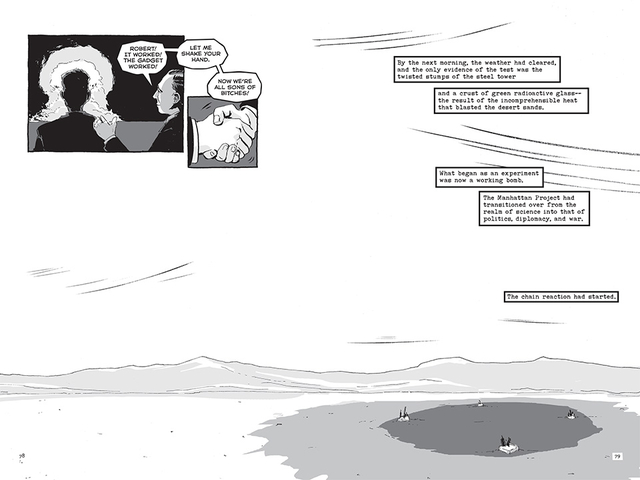

It was that feeling of secrecy, duty, paranoia, and fear, that Fetter-Vorm tried to capture as he researched, wrote, and illustrated Trinity: A Graphic History of the First Atomic Bomb (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012). Combining history, politics, science, and philosophy in what others would call a graphic novel format, Trinity visualizes the steps that led to the destruction of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Its art seduces, as its content condemns.

In a sense, this is well-covered ground for graphic novels. We have had moving, provocative stories of the preparation and after effects of America’s atomic bombs, like Keiji Nakazawa’s heart-breaking manga about Hiroshima, Barefoot Gen, and Jim Ottaviani’s Fallout, which focuses on Leo Szilard’s race against the Nazis and J. Robert Oppeneimer’s later troubles. Fetter-Vorm’s work is notable, however, for its simultaneous expressiveness and restraint; graphic novels often have an advantage over prose in what they can ‘show,’ not ‘tell.’ Fetter-Vorm pored over thousands of photographs of the Manhattan Project, held in archives around the nation, using them as references to visually express what might otherwise feel tired, bombastic, or exploitative. In 160 pages, Trinity covers the entire process of developing the bomb, its initial deployment, and the beginnings of political fall-out, but it does so almost telegraphically. This effect is what makes Fetter-Vorm excited about the form: graphic books, he says, can straddle “the line between fiction and fact in a way that more closely approximates how we understand history in our daily lives, as a sort of collage of implications and truths.”

The hardest part of the project was following the momentum of the bomb’s development to their hard conclusion, their legacy at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Fetter-Vorm says he left the scenes with Nagasaki’s survivors for last, neither wanting to sensationalize nor undersell their pain.

He succeeded. Trinity is scarily elegant, as you’ll see in the following excerpt, which Fetter-Vorm has shared with The Appendix. We are honored to share it with you today, and we look forward to Fetter-Vorm’s next project, a graphic history of the American Civil War told through objects: opera glasses, leg irons, a bullet, a death letter.