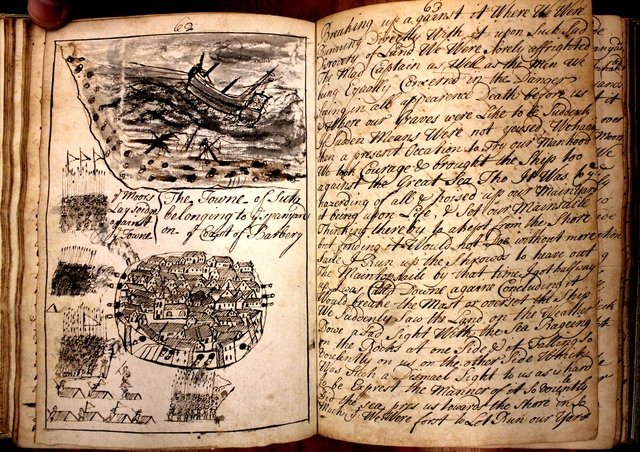

The Many Lives of Ned Coxere: Were British Sailors Really British?

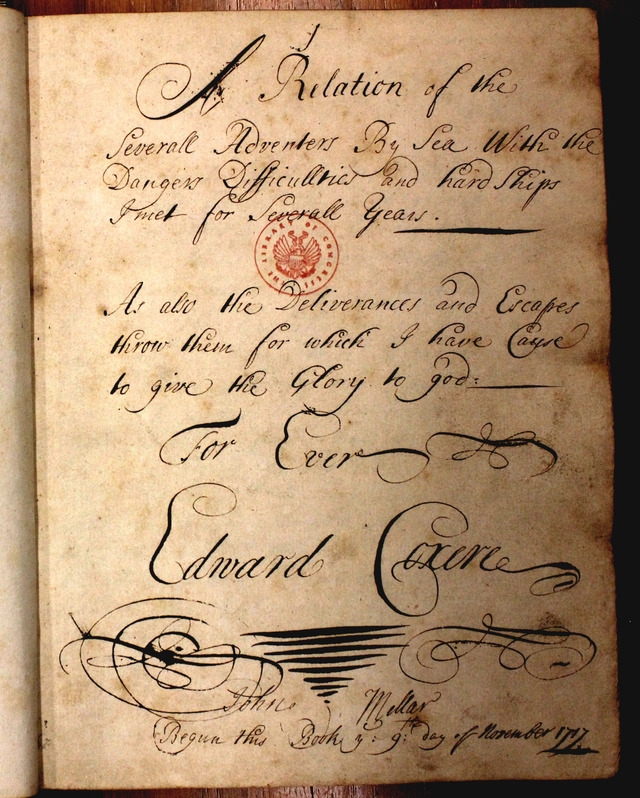

The Spanish Man-of-War is bearing down on the English merchant ship and Ned is in the cabin, stuffing Barbary Ducats into his hat and shoes. After escaping from Spanish captivity, the English Navy’s press gang, and slavery in North Africa, Ned Coxere is no stranger to hardship—or to getting out of sticky situations. After he was ransomed from Barbary slavery in 1658, this resourceful polyglot landed a spot aboard an English merchant vessel. The captain, Peter Merit, hired Ned (with his fluent Dutch and worldly demeanor), to play the part of a Dutch merchant—going ashore in a small boat with four or five Dutch sailors in order to trade with the Spanish, with whom England was at war. The ruse was so meticulous that, as Ned tells it in his narrative of his adventures at sea, “they had writings all made in Dutch my name was to be Peter Johnson of Amsterdam and had close [Ed. note—“clothes”] fitted after the Dutch fashion.”

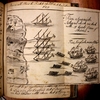

Ned and the English merchant ship had planned to sail for the Canary Islands “Richly Laden with Bees wax, sheld almonds, goats skins, with a quantity of pieces of eight and Barbery gold,” but instead, they are under fire from the Spanish. Outnumbered and outgunned by the warship, the crew can see their ultimate fate, and Ned is pocketing loot before being taken prisoner. When the Spanish finally board, they fall “aplundering, pulling of[f] our mens close from of[f] there Backs.” Ned, however, dressed only in his hat, shoes and shirt, avoids their notice.

Then the unexpected happens. Humphrey Mantlle, a sailor from Ned’s hometown of Dover comes aboard with the Spanish and immediately recognizes Ned. Humphrey had been taken prisoner by the crew and “for his Liberty Entered himself as one of there Company & Fought against us so came aboard to plunder.” Ned promises Humphrey half of the Ducats he had secreted away, if Humphrey will take the coins and hide them. He agrees, and an instant later Ned is carried on board the Man-of-War where as he later recounts, “these spanyards were so Greedy for Gold that they striped us into our shirts & felt behind my Ears.” Ned and his crew are then thrown into the cold and stinking hold. How would Ned escape?

By employing that old familiar scheme of his: impersonation.

Ned’s life as a linguist, adventurer, and master impersonator began at fifteen, when his parents sent him to France so that he could learn the language and prepare for a life of global commerce. His early introduction to French was followed by Dutch, picked up while working aboard a Dutch merchant ship, and Spanish, which he learned when the Dutch ship was sold to the Spanish Navy. He could also speak the Mediterranean Lingua Franca—a pidgin language that combined various Italian dialects, Arabic, Spanish and Portuguese—which he learned during his time as a slave at Ghar El Melhn in Tunisia. This talent for language allowed him to move through the Mediterranean with ease. In a dangerous seventeenth-century era of warring states, marauding ships, and so many obstacles to trade and personal liberty, it was his passport.

Ned Coxere and his fellow sailors inhabited a world plagued by nearly constant warfare. Between his birth in 1633 and his death in 1694, England was continuously involved in conflicts with a succession of other powerful states: Spain, France, and Holland. English ships were also often under threat from North African privateers. And while kings, emperors, and oligarchs waged war, their subjects made do. Some captains took advantage of these circumstances by obtaining a letter of marque, which was a government license to plunder enemy ships. Others resorted to trickery and deception to avoid conflict. Ships often flew colors of neutral states to prevent attack by their enemies. And many sailors, like Ned and his boatful of Dutch seamen, impersonated men of other nations to facilitate trade.

Sailors were able to fake their national identity due to the cosmopolitan nature of maritime life: they were used to working under various flags and among diverse cultures and languages. Sailors like Ned worked with men who came from every corner of the globe: not only from all of the British Isles and Europe, but also from the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Eager to limit the multitude of nationalities aboard their merchant vessels, the English government would pass the Navigation Act of 1660, which required that three out of four seamen on English ships be subjects of the crown. Even after the passage of these acts, the state itself admitted that in times of war more than half of many crews were not English. Collected from ports all over the globe, these crews could be a ragtag bunch. “Such unaccountable odds and ends of strange nations come up from the unknown nooks and ash-holes of the earth to man these floating outlaws,” Herman Melville wrote of whalers in the nineteenth century. “The ships themselves often pick up such queer castaway creatures found tossing about the open sea on planks, bits of wreck, oars, whaleboats, canoes, blown-off Japanese junks, and what not.”

Work aboard merchant ships provided mariners like Ned with shorter voyages and better wages than the Navy, where conditions were terrible and pay was low. Merchant ships also offered better opportunities for prosperity in the form of “venture”—a personal stock of goods individual sailors could bring aboard in hopes of making their own profits. But merchant ships didn’t free sailors from the threat of war, violence, and captivity—it made them more exposed to the threat of attack by privateers. And when a voyage went bad, as Ned’s just has, deception was often the only way out.

Down in the reeking hold of the Spanish Man-of War, Ned and his crew are miserable. They are given little water, and that they do have is fetid. But the thought of his gold Ducats revives his spirits. It means that he will not starve once he is sent ashore to prison. When they arrive in Cadiz, however, he learns that his friend Humphrey has run away aboard a ship bound for Holland. Desperate at the thought of rotting in Spain, Ned begins to plan his escape. “My next work was to put all the Ingineuaty I had at work how to Cheat the Prowd spanyards of a Prisoner the second time,” Ned recalls.

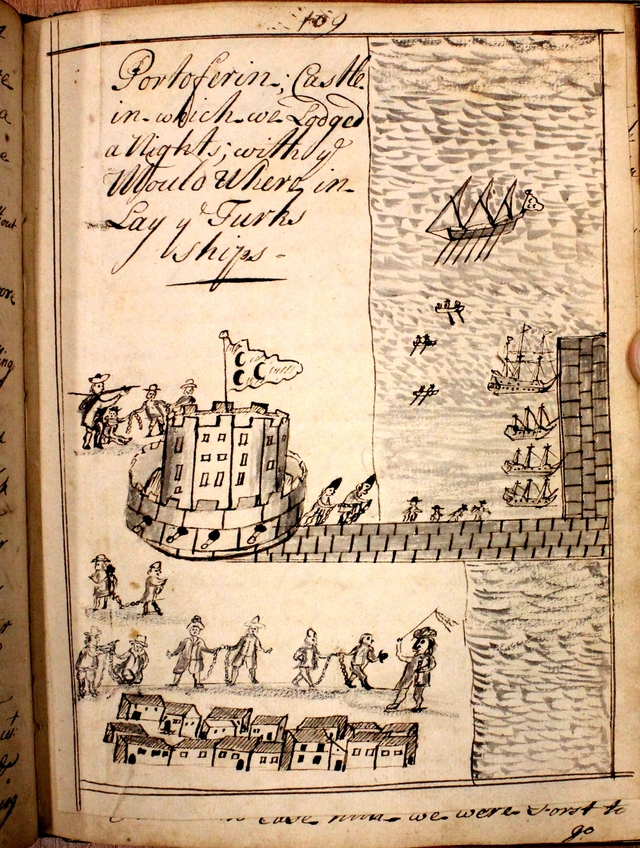

Put to work above decks on the Spanish Man-of-War, Ned falls into conversation with one of Humphrey’s friends. When Ned tells his story, the friend takes pity on him, giving him a piece of eight. Ned hopes to use it to get aboard a Dutch ship that is anchored in the bay close by. Ned bides his time. A Spanish boatman comes aboard to sell wine, and Ned sees his opportunity. Ned does his best to blend in with the Spanish crew. With his fluent Spanish, he succeeds. He offers the boatman a quarter of his piece of eight for passage to the Dutch ship. The boatman, thinking Ned is a subject of Spain, and not an English prisoner, agrees. When they reach the Dutch ship, Ned pays the boatman, who “went about his Busines, not knowing he had cheated the King of a prisoner.”

Being abandoned by his friend and robbed of his Ducats would only wound Ned temporarily. As much as he was a sailor of the world, he was also a Dover man, and those bonds of trust and obligation were still strong. Eventually, Humphrey gave half of the Ducats to Ned’s wife. Safe and sound back in Dover, Humphrey could not risk damaging his reputation by withholding Ned’s share. These were home ties worth defending. Like Ned, seamen often married women from their hometowns, and returned there after a life at sea. Ned’s wife, Mary, like many mariners’ wives, managed her husband’s affairs when he was away, often selling cloth and other goods he had brought from abroad. Some sailors even gave power of attorney to women in their families. This allowed the women to collect wages, make property transactions, and appear in court to do business in their kin’s name. Having absent husbands thus gave wives like Mary more independence than many other women of their day, and they participated in the same trade and trust networks as their husbands. These networks helped reinforce the importance of homeport reputation, even in the mobile world of sailors.

Yet just as important were the bonds made at sea. Historian Marcus Rediker argues that isolation from traditional social structures such as family and church allowed sailors to create a “community apart”: their need for collective safety in the face of dangerous working conditions strengthened their solidarity. Britons had long described sailors as a “nation apart”: tanned, tattooed and with strange clothing and customs, British sailors seemed “a generation differing from all the world.” Sailors from across the globe could be bound together by shared sufferings and experiences at sea as well as by their marginalization from larger society at home. Adding to this sailors’ solidarity, Ned’s linguistic skills not only allowed him to fake his nationality, but also to create connections. His ability to move between cultures helped him to bond with sailors from different nations and encouraged a wide variety of sailors to sympathize with his plight. Perhaps after years at sea he and his fellow sailors had more in common with their brethren aboard than with their own countrymen.

To what extent then, could Ned—fluent in Dutch, French, and Spanish and living a sailor’s life since the age of fifteen—be considered an Englishman?

Once aboard the Dutch ship, Ned fell in with the steersman who, as Ned puts it “seemed to have pity on me I having the Languidge it took the more with him to plead with the skipper to keep me on board.” Dutch was not only a means of communication, but also a shared cultural connection. The steersman saw Ned as a compatriot, and thus someone who, like himself, deserved pity. And when the skipper finally agreed to let him on board, Ned found that the crew was half French. Once again, Ned recalls, “I having the French tongue got into favour with them.” Ned wasn’t just impersonating men of other nations; these were real cultural transformations that added to his bag of escape tricks, and then transcended them.

He could be anyone and go anywhere. Almost.

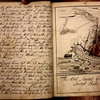

After a short time aboard the Dutch ship, Ned got passage to Faro, Portugal where he heard of two English vessels “sixteen miles from thence at a place called Tavira.” When he was set ashore, however, he and his friends found themselves alone on a deserted island. On the beach, they looked out at the empty sea. How would Ned escape this, his latest imprisonment?

“We stood gaseing & knew not what to do.”