Levitation: Physics and Psychology in the Service of Deception

The science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke once proposed three laws for sorting through predictions of the future. The third is the most famous, for good reason: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

It’s a “magic” that can wear off fairly quickly, once the audience grasps that technology. But for historians of science, it’s a useful reminder of why people believe what their experience of the world tells them shouldn’t be true. And as such, it’s a damn good guide to the history of prestidigitation: stage magic.

Clarke’s law comes quickly to writer Jim Ottaviani when asked why he and the artist Janine Johnston made Levitation: Physics and Psychology in the Service of Deception, a comic book history about the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century illusionists that invented, stole, and perfected one of the greatest tricks ever performed on stage: the levitating woman.

Ottaviani, a former nuclear plant operator and current librarian at the University of Michigan, turned to telling scientific history in comic book form after reading Richard Rhodes’s The Making of the Atomic Bomb. He and his many artistic collaborators have since delivered a steady stream of award-winning, New York Review of Books-praised fare, like his most recent work Feynman, about the famed Nobel-winning, Challenger-debunking, bongo-playing, Manhattan Project physicist. His next book, Primates: The Fearless Science of Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Birute Galdikas, drawn by Maris Wicks, comes out this June.

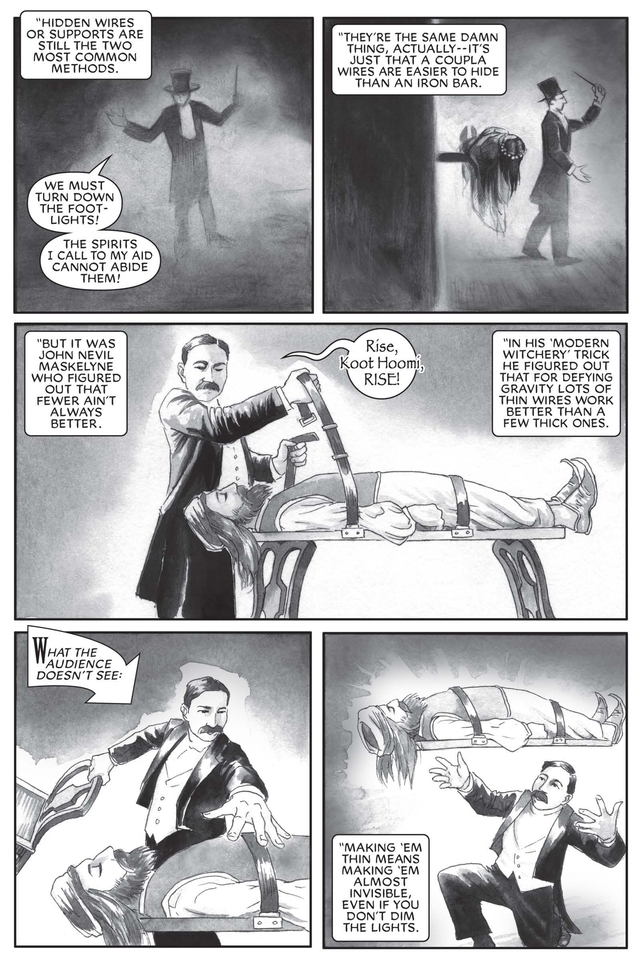

Still, Ottaviani doesn’t feel like he strayed from ‘hard’ science to write Levitation. “Throughout the history of magic, science and technology that was not yet widely understood was used to baffle and amaze people,” he writes.

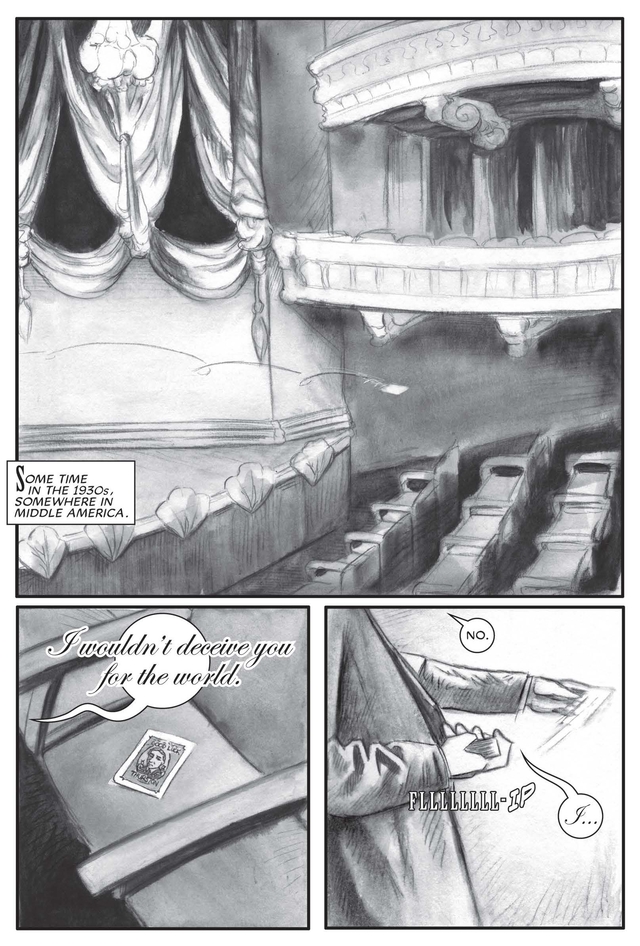

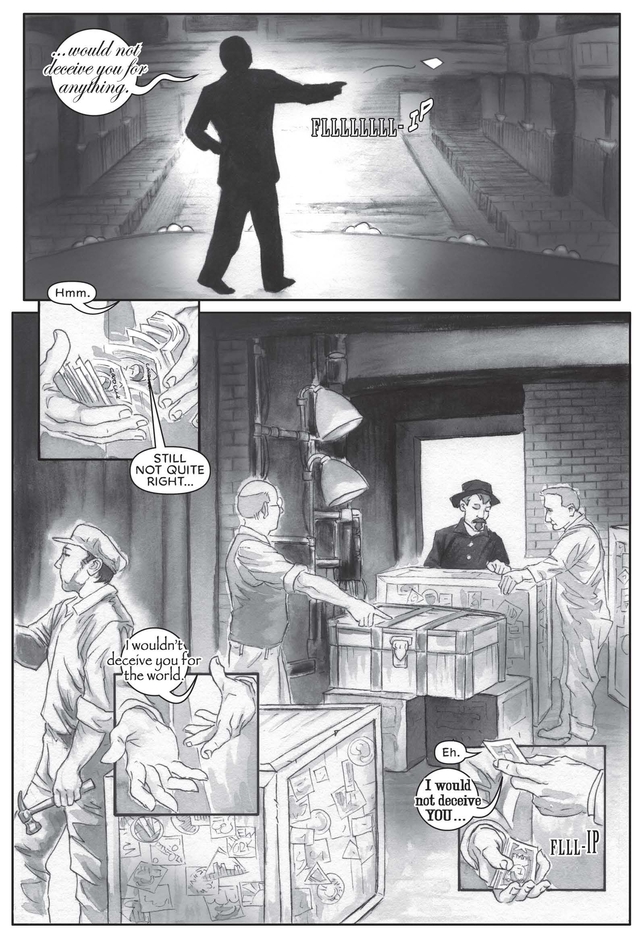

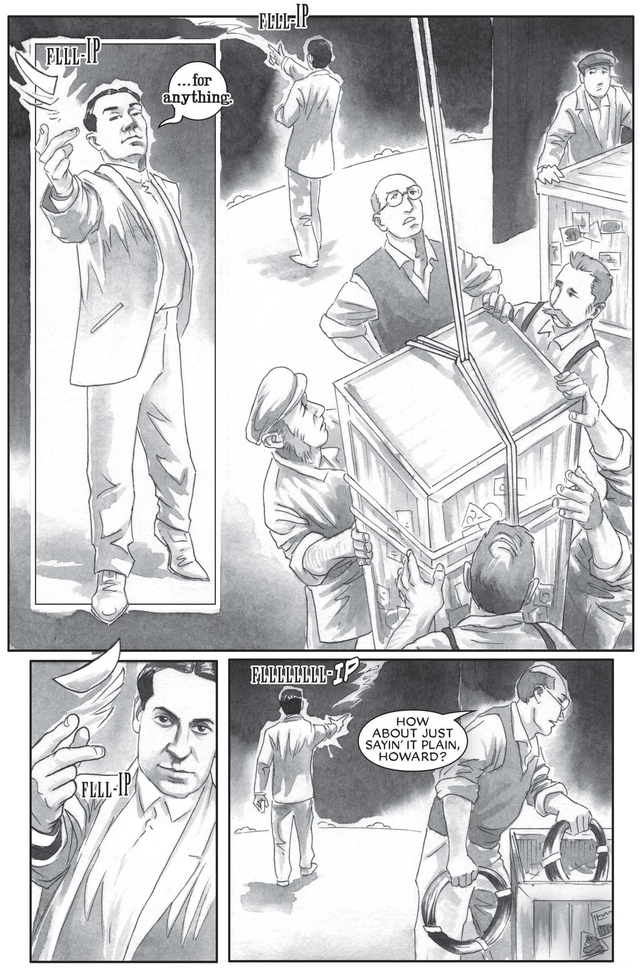

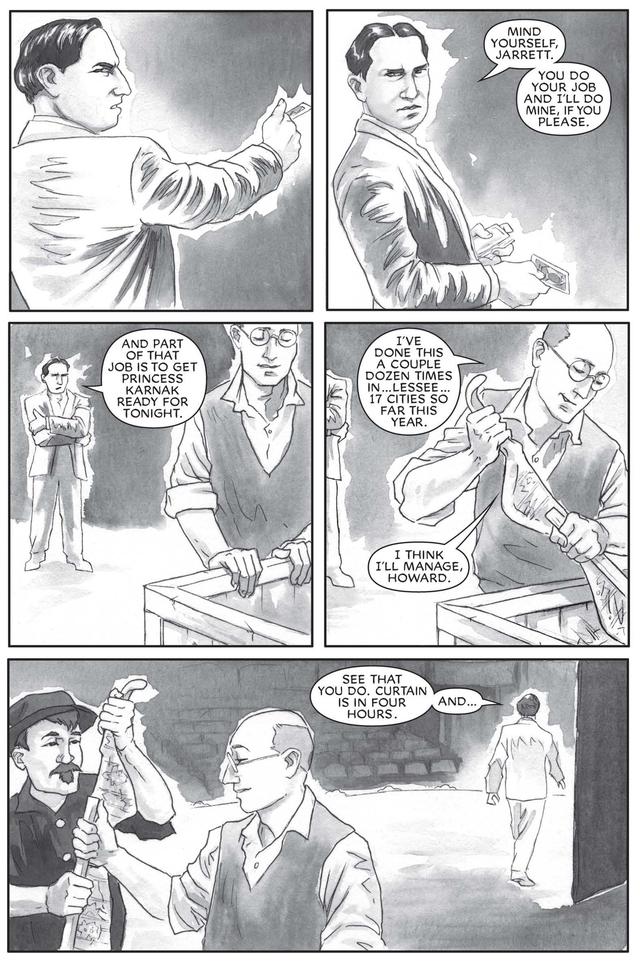

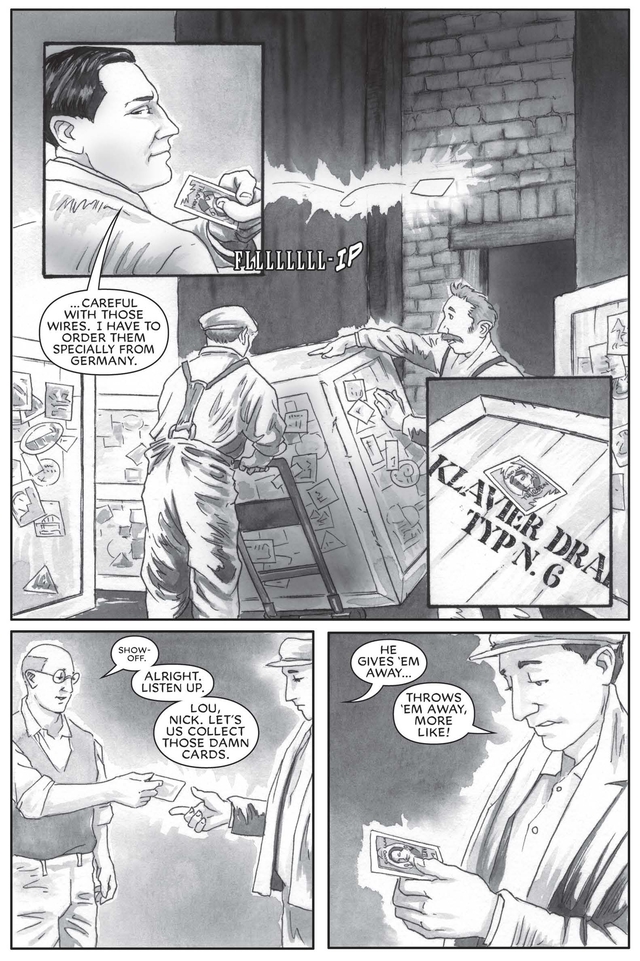

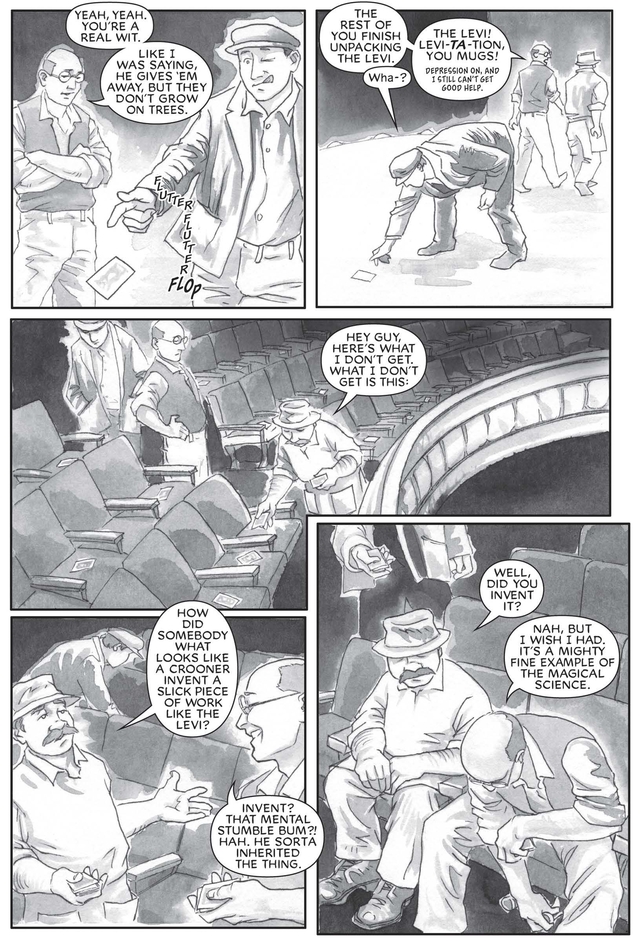

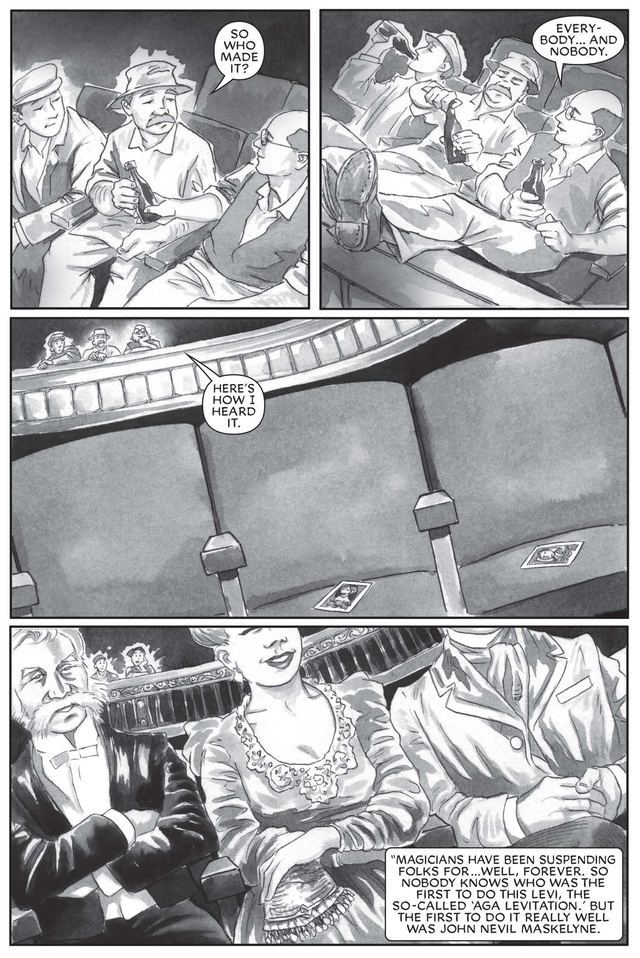

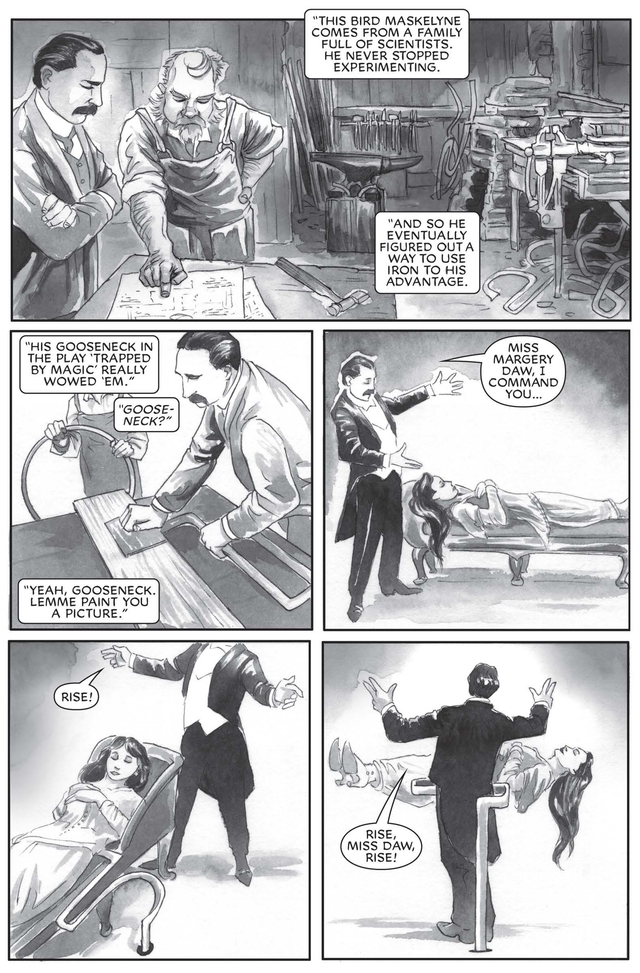

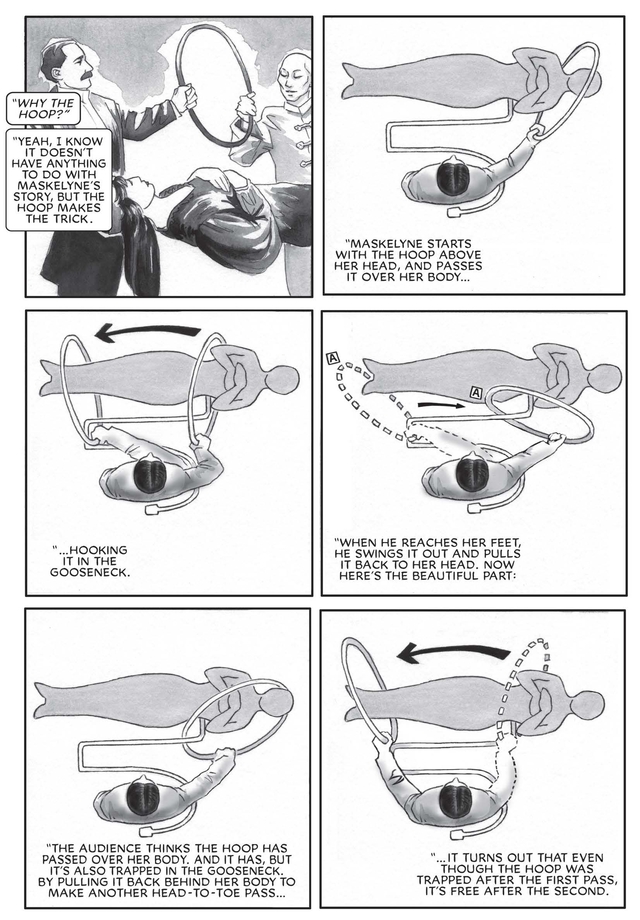

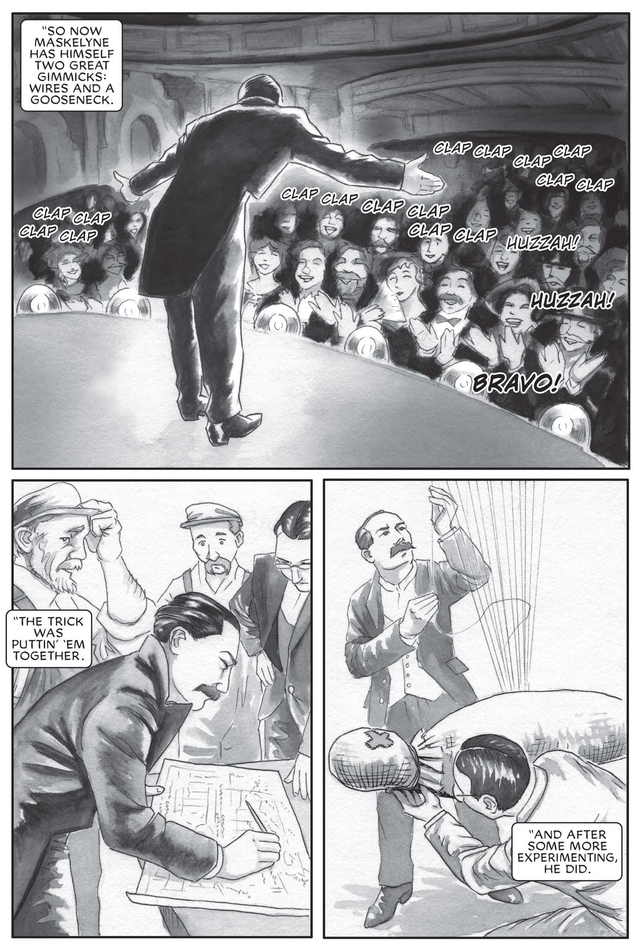

Ottaviani believes that the explanatory power of Levitation, like his other work, begins with his background in engineering: the ability to take “things—be they theories or stories—apart to find out how they work or where they came from and [put] them back together via pictures.” He’s quick to add, however, that readers don’t see his script, “so the success of a story hinges 100% on the skill of the artist every time.” The artist on Levitation, Johnston, sells the story with excellent face and body work, fin de siècle scenery, and, most importantly, the ability to convey both the physics, process, and wonder behind the levitation trick.

Levitation is an excellent piece of storytelling and explanation, delivered from the perspective of the stagehands that suffered the 1930s magician Howard Thurston. According to Thurston’s predecessor in the levitation trick, Harry Kellar, Thurston broke the illusion by inviting audience members up on stage to examine it. But did Thurston ruin the trick? Or did he just demonstrate another layer of its power?

We’re excited to excerpt its opening pages in this issue of The Appendix—and we should add, if you’re wondering, the full text doesn’t stint on the reveal.