From the Aviary: Haliaeetus leucocephalus

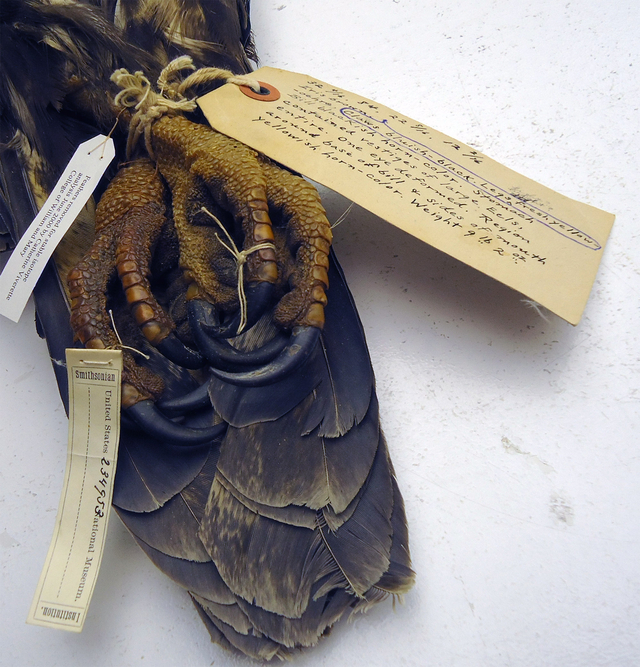

Today I pulled an eagle out of a drawer. There were three or four other eagles there, also female, but I was looking specifically for her. I recognized the handwriting on the tag, and turned it over for confirmation. Yes. She was lying on her back, neck extended, sharp claws crossed and secured. I carefully lifted her with two hands, and even though she is a skin—a shell, really, her organs and skeleton replaced with stuffing—I felt her weight.

I wasn’t prepared for the eagle—for her size, for the impact that holding her in my hands would have on me. Historians talk about material culture, about the importance of engaging non-textual sources in our work and in our teaching, but, holding her, I was almost giddy. It was more than that feeling that you’re looking at the coolest, biggest, weirdest thing in the archive; when you require the white gloves, a bigger book cradle, a stand for viewing large format photographs. She had been alive once. And I felt something. Connected through the feeling of her feathers on my fingers, the proximity to something I’d only ever encountered at a safe distance.

I carried her to one of the work tables in the center of the collection space, and looked, really looked at her under the exam lights. Haliaeetus leucocephalus. The Bald Eagle.

She was as he’d described, though I hadn’t been able to conjure an image from his details alone: “Bill blackish…Legs + feet yellow ochre. Talons bluish black.” He listed her weight at nine pounds, two ounces on September 15, 1874. It was the week Edgar Alexander Mearns turned eighteen. He shot her near his home in Highland Falls, NY. It had been her home, too. Her feathers are brown; she hadn’t yet developed the iconic “bald” coloring of a mature bird. Mearns marked her juvenis, a juvenile specimen, not fully grown. The same could be said for Edgar, still in school, his future open, uncertain.

He did good work. This isn’t taxidermy; it’s scientific preparation. These birds are laid flat and preserved for future study, not mounted in life-like poses as art or decor. Even as a very young man, Mearns made skins as good or better than more experienced collectors before and after his time. The incision is neatly sewn and hidden beneath the feathers; the body is stable, anchored by a stick carefully positioned skull-to-tail inside. And, of course, she’s still here. The skins Edgar prepared as a teenager have long since survived him, and they do more than affirm his skill. They tell his story, a story I am following because of what it connects: nature and empire, West with East, life and work.

“The artifacts of a life’s work: birds and mammals with small, steady sutures in their bellies.” Photograph by the author. National Museum of Natural History, Division of Birds.

Mearns would rely on that precise stitching all his life. He went to medical school and joined the army. He took a commission as a surgeon at a post in the Arizona Territory, where he hoped to have opportunities to pursue his interest in the natural world. And the notes he made, the measurements he recorded, the specimens he skinned and prepared, these things he did in every place he served: they link Arizona and Minnesota out West with Luzon and Mindanao in the Philippines, forts in Rhode Island, Texas, Georgia, Virginia with the forests and meadows of Highland Falls. After twenty-five years of service, Mearns retired from the army but never from collecting. In 1909, he was one of three Smithsonian associates who accompanied Theodore and Kermit Roosevelt’s famed African Expedition. The artifacts of a life’s work: birds and mammals with small, steady sutures in their bellies, descriptions of animals observed and collected, lists and notes and letters; they are here, at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, in cabinets, drawers, and boxes.

My search revealed far more than this single bird. The collections are organized taxonomically; birds are grouped by genus and species, with specimens past and present mixed together, almost touching. The cabineted corridors of the Division of Birds are arranged according to Linnaean names. Imagine a card catalog in a code you never learned, or don’t remember. As a historian, I find this organization fascinating, and also slightly unsettling. Birds from different centuries, in this system, can lie side by side. This isn’t how historians tend to think about the passage of time. But I’m learning that attention to taxonomy doesn’t preclude an attention to chronology; it’s just a different chronology inside the cabinets, one based on ecological cycles rather than on forward motion. Many North American bird species are further sorted into males and females, adults and juveniles. And then they are grouped by month. The plumage of a bird collected in May might vary from a November specimen. Fall months more often produce young birds, battling the odds to survive until maturation. And perhaps most importantly, as migrants, always in motion, when the birds are in a particular place matters far more than which year it is.

I often feel like a migrant, following my work to wherever it takes me. Right now, I’m in DC. Soon, Ithaca, for the arrival of spring, After that, Chicago. And then, home again? If Ithaca can be called that, yes. I’ve lived there for five years, but I know I will not stay. My future home is uncertain. And this is how the birds help me. They live in motion. When it is time to move again, I think I will find this comforting. Maybe home doesn’t need to be a place. Maybe having a cycle, a rhythm governing change, is enough.

Did Mearns think this way? So many of his movements were beyond his control. The army ordered him around the West, and then around the world. They allowed him to spend his sick leave with his birds, organizing, studying, learning—but his papers contain letters that regret to inform him that additional leave time or museum assignments aren’t possible; he simply cannot be spared. And so I wonder if bird-skinning was also home-making for Edgar Mearns, if this focus on birds seen, shot, and skinned everywhere—no matter where—might have been one of the ways he coped with the uncertainties in his life and work. Unable to choose where he would be, he followed birds everywhere.

And I’ve been following him: to Fort Verde, Arizona, last summer, and to the Museum of Natural History, where I stand considering this now flightless, lifeless bird on the collection table. I looked for her because of him, to understand his life, his work. But the more time I spend with this eagle (or my eagle, as I’ve begun to call her), the more I begin to wonder about her story. Did she migrate? Some eagles do, though their patterns of movement aren’t as fixed as the routes traveled by other species. Immature eagles, in particular, wander quite a bit as they figure out how to hunt, soar, and survive through the winter. I think about this, and realize the empathy I’m registering for this process of growth. And then I remember that she’s dead, and has been for more than a century. She didn’t mature, find a partner, reproduce. Instead, her death was part of Edgar’s development—not just as a naturalist or a surgeon, but as a person. And now she’s part of mine.

“Bill blackish… Legs + feet yellow ochre. Talons bluish black.” Photograph by Brian Schmidt. National Museum of Natural History, Division of Birds.

Acknowledgements:

Special thanks are in order for Christina Gebhard at the Division of Birds. When I asked, after a week spent looking at Mearns’s papers in 2011, if we could look at one of his birds, I never imagined it would lead to a collaborative project and lessons in bird preparation! Christina offered thoughtful comments on a draft of this piece, and Brian Schmidt fielded lots of questions about birds and their collection, and in addition, kindly shared his photography skills (see his handiwork above). Thanks also to Josi Ward for generously reading, critiquing, and encouraging multiple drafts of this essay.