Mother Machine: an ‘Uncanny Valley’ in the Eighteenth Century

A late eighteenth-century “birthing phantom.” Unlike Smellie’s machine, these were not intended to be exactly like the living body, but rather a basic replica allowing midwives to understand the position of the child in the birth canal. By permission of the Dittrick Medical History Center and Museum

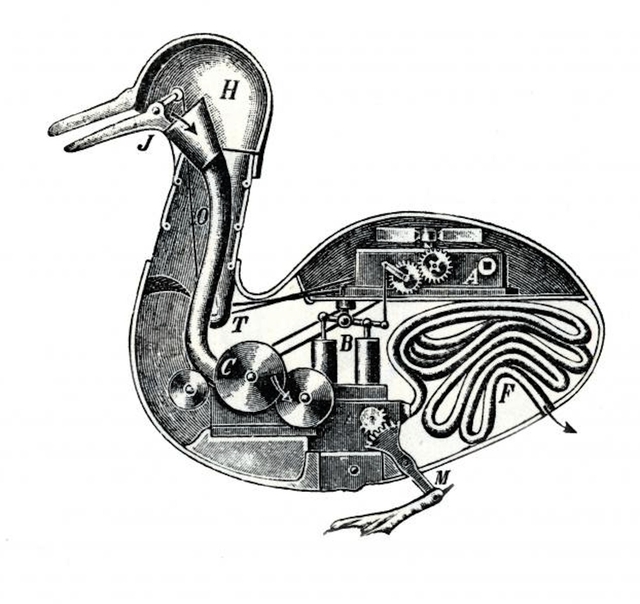

The eighteenth century was an age of mechanization, from Cartesian conceptions of animals as machines to nerve theory and early experiments in electricity. Mechanists argued that interaction among the body’s parts, its “animal machinery,” was responsible “for all vital and mental processes.” Ingenious technicians constructed automata like Jacques Vaucanson’s Flute Player, which debuted in 1738. A year later, the surgeon Claude-Nicolas Le Cat published a description of an “automaton man” in which “one sees executed the principle functions of the animal economy.”

Clearly, then, when Scottish man-midwife William Smellie unveiled his new teaching tool, this “female machine” was among friends. There was, however, a crucial difference in the design. As I have noted elsewhere, these other devices and models demonstrated musculature for the viewer and so were the ‘main event.’ The mechanical woman, as a ‘mother,’ is instead operated by the physician. She had no head—and in consequence, no mind of her own. And yet, she brought forth little machines; she reproduced leather dolls with moving parts. She existed at the outer limits of reproduction, as both a curiosity and a piece of (uncanny) eighteenth-century high technology.

This curious machine was meant to answer the problem of the moment: how to provide sufficient training for new (male) midwives—all 900 of them—without further endangering living women? It created, however, more problems than it solved, and today it leaves us with more questions than answers. Despite its popularity, the machine disappears by 1780. Unlike the well-preserved plush birthing doll of French midwife Madame de Coudray, no extant copies of the Labour Device remain. Stranger still, there are no models, no sketches and no official descriptions as provided by the designer. What was it made of? How did it work? Why did it foster such vitriolic debates? The answer lies, in part, with the fragile, even permeable boundaries between matter and mind, body and being, machine and mother.

Finding oneself in an eighteenth-century medical theatre was an unsettling experience, one usually reserved for those who no longer needed the doctor’s healing hands: the anatomy corpse. There were exceptions, however, such as the labor and delivery of pregnant women. Though the period saw the rise of notable practicioners of midwifery in Britain, including the ‘Father of British Midwifery’ William Smellie, women still died—and frequently. The greatest killer was puerperal fever, or septicemia, which they caught from the very doctors who delivered them (Ignaz Semmelweis, the ‘Father of Infection Control,’ wasn’t born until 1818). Statistics collected by Ruth Perry suggest that septicemia was “ten times as dangerous as venereal disease” (in an era when that was no small matter). Perry also reports on a number of “monster” birth cases, from the famous Mary Tofts case, who feigned giving birth to rabbits, to one about a dead infant being half-consumed by live snakes. These stories may speak of “helplessness and fear in the face of women’s unpredictable and powerful reproductive capacities,” but they also reflect an increasing desire to control female fecundity, shake off the horror of childbirth, and make the entire birthing process a workman-like affair. The unpredictable nature of the woman in labor and the mysteries of the womb led medical professionals to develop increasingly complex ‘birthing’ machines on which to practice and teach delivery.

In the seventeenth century, childbirth rituals were usually female, overseen by the midwife and various female friends, relatives and servants. In the eighteenth century, however, male surgeons took over the bulk of the practice. This shift was not without controversy. Female midwives like Elizabeth Nihell lobbed vitriolic attacks at male midwives—and on the birthing machine’s creator—for releasing “swarms” of male midwives into practice at the “expense of humanity” and decency. Already an experienced practitioner, Smellie studied the methods of French instructor Gregoire the Younger, but disappointment led him to develop new and better instruments (like augmented forceps) and a better way to practice their use: the Labour Device, or mechanical woman. Smellie wanted to use a device that would render the internal machinery of the female body distinct, while allowing his pupils to get a feel for delivery without endangering the living subject. The machine became the patient in the medical theater, one of the most unusual of the eighteenth century’s collection of mechanical automations.

An apparent ‘mechanical genius,’ Smellie contrived devices that earned him the awe of his students and even of his detractors. One of Smellie’s pupils writes:

[Dr. Smellie was] An uncommon Genius in all sorts of mechanicks, which after having shewed itself in many other Improvements he manifested in the machines which he has contrived for teaching the Art of Midwifery. Machines which Dr. Desaguliers, who frequently visited him, allowed to be infinitely preferable to all that he had ever seen of the same kind, and which I (from having seen those that are used at Paris) will aver to be by far the best that were ever invented.

This “apparatus” allowed Smellie to “perform and demonstrate all the different kinds of Delivery with more Deliberation, Perspicuity and Fulness than can be expected on real Subjects.” It differed from other mechanical obstetrical devices, which were “no other than a piece of basket-work, containing a real pelvis covered with black leather, upon which he could not clearly explain the difficulties that occur in turning children.” Being “little satisfied” with this method of instruction, Smellie resolved to create “machines which should so exactly imitate real women and children as to exhibit to the learner all the difficulties that happen in midwifery,” and he refers to his creative trials as his “labours”—a strange birth story in itself.

That Smellie was successful is evident from the notes of students and collections of advertisements—as well as from the attacks he weathered. In A Treatise on the Art of Midwifery, Nihell refers to the device as “his automaton or machine,”

[a wooden statue], representing a woman with child, whose belly was of leather, in which a bladder full, perhaps, of small beer, represented the uterus. This bladder was stopped with a cork, to which was fastened a string of packthread to tap it, occasionally, and demonstrate in a palpable manner the flowing of the red-colored waters. In short, in the middle of the bladder was a wax-doll, to which were given various positions.

From this benign and even laudatory presentation of the “ingenious piece of machinery,” Nihell proceeds to question its functionality. She asks if students can really learn an appreciation of the tender parts of a woman from a doll that does not feel, does not speak. What disturbs Elizabeth Nihell is not the mechanics, but the fact that it approximates the body so nearly, yet without sensation. Smellie’s greatest critics seem most appalled by the machine’s incredible approximation to the true body in labor. It is—to put it another way—too much like the real thing.

From student notes, we know that Smellie apparently added “ligaments, muscle and skin in artificial materials” to make the figure more life-like and, in the words of his pupils, to lay “every material circumstance […] open to the naked Eye.” They were composed of real bones, covered with artificial ligaments and muscles and had the “Motion, Shape and Beauty of natural Bodies […] with great Exactness.” Similar descriptions are to be found among advertisements, tucked into arguments of detractors, and in contemporary pamphlets; these are (unsurprisingly) quite difficult to locate, and problematic biases make them even more difficult to judge. Johnstone collects the best and most reliable of these descriptions in his biography, including A Short Comparative View of the Practice of Surgery in the French Hospitals, which explain the mechanics: “The Uterus Externum and Internum [sic] are made to contract and dilate according to the Difficulty intended for the Delivery.”

More mysterious yet is the extended description provided by surgeon Dr. Peter Camper. After attending Smellie’s lectures, he described the function of the machine as having abdominal and extra-abdominal muscles “made out of leather with such remarkable skill that not only is the structure as natural as possible but the necessary functions of parturition are performed by working models.” Camper described the “contraction of both the internal and external os, the generation of water in parturition and dilatation of the os uteri are so natural that hardly any difference is to be noticed between these, and those in natural women [my italics].” The fetuses are likewise described as imitating nature not only in size but in the natural movement of parts, of joints, and even of the moveable skull bones. These dolls were, says Camper, “excellently contrived, they having all the Motions of the Joints. Their Craniums are so formed as to give way to any Force exerted, and are so Elastick that the Pressure is no sooner taken off than they return to their natural Equalities.” Afterbirth was represented by “various leathers,” and the “change in the os tincae are noted and made clear by colours.” One of Smellie’s opponents—Douglas—claims that the machine also had “shoes, Stockings, and the common Apparel of Women.”

Such descriptions toy with the imagination: elastic, and yet mechanized; sinews laid open and yet fully clothed; hardly distinguishable from “natural” women, and yet headless and giving birth on the order of once an hour. It’s either high praise, or a serious indictment of eighteenth-century patriarchy, which seems unperturbed by so monstrous and mindless a mother. But the mystery of its composition is worth considering further. India rubber was not readily available or understood until at least the mid-eighteenth century—and only recommended for medical use after 1768, when researchers Hérissant and Macquer recommended that it could be used for probes and tubes in laboratories. That Smellie constructed elastic, reforming craniums for his doll fetuses without it is, in itself, remarkable (and may explain why they are considered both more “natural”—that is, more lifelike—as well as strangely “unnatural”—that is, peculiar, odd, beyond comprehension). Was it a kind of stretched leather? Oiled or greased to keep it supple? Was it, like the French model of Mme. Coudray, made of cloth? Were there joints and hinges? And were they made of bone or metal and springs? How could the colored leather be described by a surgeon as “indistinguishable” from the real thing?

These are fair questions, but there is a better one: Why, if this machine was such a wonder, are there no illustrations of it? We know that Dr. William Hunter was in attendance at the auction and bought one of Dr. Smellie’s devices. Hunter himself did not illustrate the device, however, and later sold it to an old pupil of Smellie’s, Dr. Edward Foster. The machine travelled to Dublin, where it made a small debut, but demonstrations were cut short by Foster’s untimely death. After this, it disappeared.

An engraving of the Canard Digérateur, or “Digesting Duck” created by Jacques de Vaucanson in 1739. Wikimedia Commons

We can speculate about the political and cultural shifts that may have led to the device’s suppression in England (a backlash against devices and forceps in the latter part of the century). But this is true, in part, of other devices—and yet illustrations remain. A casual internet search for ‘obstetric phantom’ will yield French and Italian models from the Giovan Antonio Galli Obstetric Museum in Bologna to the surviving phantom of Madame du Coudray at the Musée Flaubert et d’histoire de la medicine in Rouen. Likewise, numerous automatons from the eighteenth century survive (the Musée du Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, Paris, even has an image of the original mechanical defecating duck). Yet, though I have searched collections and even the market trade in medical artifacts, I can find no trace of either the mechanical mother or fetus. All that remains is the list catalog of artifacts auctioned off after Smellie’s death. The machines appear (amid other scientific preparations) as Lots 103-106:

103. No. 1. A Machine contrived for explaining all natural and easy Labours, and likewise difficult Labours, where difficulties arise from the Circumstances of the Child.

104. No. 2. Another Machine of the same Constructions, but so contrives as to explain the Difficulties which happen in Labours, from the Narrowness of the Bones of the Mother. In this Machine, besides the under part of the Uterus, &c. are represented the Great Vessels on the Vertebrae of the Loins, with the […] Spermatics, and the Kidneys, all in the natural State.

103. No. 3. Another. This Machine is made with great Care, exhibiting not only the Uterus (which contracts and dilates) with all its Appendages, but all the different Bowels of the Abdomen.

106. No. 4. A new Machine finished (but not put together) by Dr. Smellie in the latter Part of his Life—The Uterus and its Appendages are so contrived as to be easily taken out and replaces by Lacing. This Machine the Dr. intended to be the most perfect, and, at the same Time, the most simple.

Lot 103, no. 1 of the catalogue describes the first (ten-year-old) machine; it still appears to be in order but, given its age, it was likely in a state of some disrepair. Lot 104, no. 2 was specifically used for showing cases of “narrowness of bones” in the mother. Rickets were a common problem, often resulting in difficult or impossible labor due to the misshapen pelvic bones; it is possible that this device was meant to demonstrate problems of this nature. The third machine features a “contracting” uterus. The final machine, no. 4, was supposedly the most advanced and, as the last completed before Smellie’s death, entirely new. Whether all of these were purchased by Hunter and then Foster, or whether they were separated, whittled away and dispersed, we cannot now know. The last trick of the mechanical mother, it seems, was a disappearing act.

As a medical humanist scholar of reproduction, I am fascinated by this strange machine and its disappearance. How could so unusual an automaton fade out of record? I searched for the machine for nearly three years, visiting three countries, two private collections, and one very knowledgeable gynecologist (with his own private museum). I have been to various exhibitions and collections, spent long hours under incandescent lights in the bowels of old libraries and equally long stretches skimming through digitized collections. But for a long time, I had simply to admit defeat; I had been unable to locate the remains, the resting place, the conclusion of this strange story. And of course many an archeological search ends just this way: many hours spent sifting sand to find… only to find more sand. But a recent trip to the Harvard Museum of Natural History offered a ray of hope. No, I did not discover the mechanical woman, laboring on in a dusty corner. (Would that it were so!) What I found instead were three-thousand glass flowers.

Glass flowers created by Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka, today housed at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. Flickr user Lostinfog

Created by artisans Leopold and Rudolph Blaschka between 1887 and 1936, the delicate beauties had been commissioned by Professor George Lincoln Goodale, founder of the Botanical Museum, for teaching botany. The results are astounding—and deceptive. The glass flowers look so real, that they do not appear to be glass at all. Of course, knowing they are not live specimens, my twenty-first century perception assumed them to be plastic, pretty but mass produced. I was terribly wrong, and my crude assumption flew in the face of the craftsmanship that clearly went into each painstaking stem and petal. But this realization led to another—should any of these treasures be removed from their hallowed space, tucked away in a back room to be found by those who knew nothing of their history, wouldn’t they be haplessly abandoned or discarded? There would be no need to render them in sketches (and I took no photos). Why bother? They are not novelties; they look just like flowers. And so, if Smellie’s ingenuity and talent ultimately resulted in a machine so like the human body that it seemed (to some) indistinguishable from it, would there have been an impetus to render it among his students? Would an anatomy (like those presented in Smellie’s treatises) do just as well? And, when discovered by the grieving widow of Dr. Foster, in a country and at a time when its previous fame was unknown, would it have been deemed worth keeping? A strange headless doll in stocking feet? Perhaps not, after all.

The machine-mother existed as an eighteenth-century “uncanny valley,” a term coined by robotics professor Masahiro Mori to describe the disruption felt when an “animated character becomes almost indistinguishable from a human” and “small deviations […] begin to unsettle the viewer.” The latter part of the eighteenth century saw the rise of the man-midwife, his future more or less assured, but the obstetric machine fell into obscurity. To midwives like Nihell, the mechanical woman was a monstrosity, but perhaps—unlike the other automatons of its time—it was not quite monstrous enough. A curiosity enthralls only at the interstices.

Inexplicable, mysterious and extraordinary, Smellie’s invention may have done more to vivify the machine than to mechanize birth—but a mechanical woman only fascinates where machine and body meet, like Frankenstein’s monster with the stitches still showing. If, as both students and detractors claim, it was too near the mark, too like the real thing, its very ingenuity may have thwarted its own legacy. Thus, despite the ‘labour’ of midwifery’s founding father, the doctor and his monstrous machine—repellent rather than attractive in its anthropomorphization—left no progeny.

Author’s Note: an early version of this paper was presented as “The Curious Disappearance of the Mechanical Mother,” UCD Irish Centre for Nursing & Midwifery History Spring—Summer Seminar Series, 2011 and as “The Father of British Midwifery and the Mother of Inventions,” Centre for the History of Science, Technology & Medicine CHSTM Seminar Series, 2011.