Jepp, Who Defied the Stars

When author and journalist Katherine Marsh set out to write her latest young adult novel, Jepp, Who Defied the Stars, she decided to go back in time: to her youth, as a teenager, when she accepted her mother’s passion for astrology while struggling to believe in free will; and to late sixteenth-century Europe, when astrology was astronomy’s sister, but the divide between fate and self-determination was widening between society’s feet.

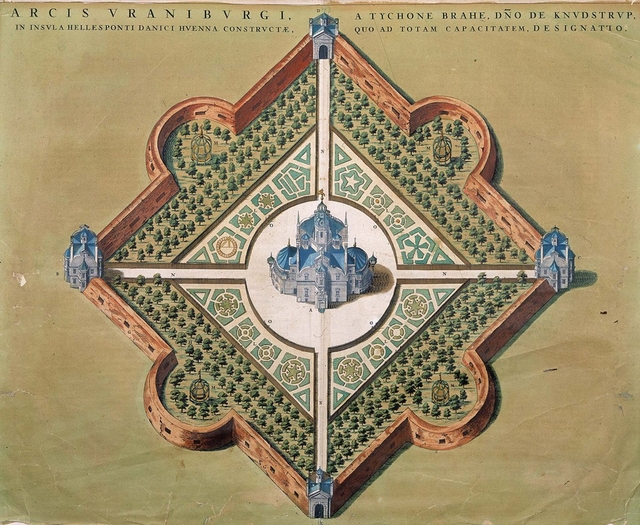

Marsh’s fascinating work of historical fiction centers on Jepp, the teenage dwarf jester of the sixteenth-century Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe at Uraniborg, the Castle of the Heavens, on the island of Hven. Brahe’s quest to map the heavens without the use of a telescope was a major moment in the history of science. It created one of Europe’s earliest international and meritocratic research communities, explains Marsh, drawing from John Robert Christianson’s On Tycho’s Island: Tycho Brahe, Science, and Culture in the Sixteenth Century.

Jepp also existed, but while we know much about Brahe—and the famed metal prosthetic nose that replaced the original he lost in a duel—we know little about the dwarf he employed. As Marsh puts it in the author’s note for Jepp, Who Defied the Stars, Jepp “is no more than a footnote of history and, beyond a few biographical details, little is known about him—including who he was or how he ended up at Uraniborg.” Marsh was captivated by the mystery of such a character and set out to tell his story.

She began his journey in a hierarchical and deeply religious world. At the turn of the seventeenth century, Marsh’s Jepp, fifteen years old and as tall as he will ever be, leaves his small village to become a dwarf jester at Coudenberg, the majestic palace of the Infanta Isabella Clara Eugenia, ruler of the Spanish Netherlands. “When I was growing up,” Marsh explains, “my parents had a wonderful book of European art, and I remember being deeply drawn to several portraits of court dwarfs by Diego Velazquez. This seventeenth-century painter, who depicted the court of Philip IV of Spain, captured a dignity and directness of gaze in his dwarf subjects that made them seem more alive than almost anyone else around them.” There was a long history of dwarfs serving royal courts, Marsh learned from Betty M. Adelson’s The Lives of Dwarfs: Their Journey from Public Curiosity toward Social Liberation. Some had power, but most were cruelly-treated status symbols. Jepp experiences a number of those real-life indignities until he decides to help Lia, another dwarf trapped in the gilded birdcage of the Infanta’s retinue.

Lia’s story ends in tragedy, however, and when the following excerpt begins, Jepp is locked in his own cage and is traveling across Europe to a destination that his driver, Matheus, refuses to reveal. It is only there that Jepp, in Marsh’s wonderful and humane re-imagining of a historical “footnote,” will escape the control of the stars, and exercise his free will. Marsh took some historical liberties to set Jepp on his path, such as extending Tycho Brahe’s time at Uraniborg past 1597, and putting the Infanta on the throne before 1599, so that Jepp’s time with each might connect. But neither choice detracts from a story that feels historically right and personally meaningful in the ways that matter. It’s a story that appeals to adults young and old, struggling at all ages with fate and free will, the wonder of the universe, awkward bodies—physical and celestial—and those all-encompassing questions, ‘Who am I? How can I live with uncertainty? And what can I do?’

We are honored to excerpt it in this issue of The Appendix.

“Uraniborg.”

This is the name the old peasant utters as he takes a hand off the horse’s rein and jabs his finger toward the gatehouse to Tycho’s castle.

As I recall Master Kees’s lessons, I realize a cruel irony of my fate: Lia is dead, my home and mother lost, my father still unknown to me. The heavens have deceived me. But it seems I cannot escape the stars, for I have been sentenced to the castle of Urania, the Greek muse of astronomy.

In the deepening shadows, I hear a chorus of frantic barking and follow the sound to the flat-roofed top of the gatehouse where a half dozen kenneled mastiffs hurl themselves against metal bars. This Hadean welcome is cut short, however, when a scrawny servant boy appears and, with a shout to the dogs, unlocks the gate. Matheus explains that he is here to deliver me to Tycho but it is only the mention of his master’s name that seems to animate the boy, who must not speak Dutch.

As he leads us onto the grounds, I can see that the castle’s name was not bestowed lightly. Uraniborg has been laid out so meticulously that it looks as if it were designed using its patron muse’s signature compass. The gatehouse sits at the vertex of two enormous ramparts, which appear to form a ninety-degree angle. A pin-straight path bisects this angle, leading from the gatehouse to the front entrance of the castle.

As we follow the servant toward it, we pass an orchard, the spindly fruit trees arranged in as orderly a formation as the Infanta’s, though there seem to be even a greater variety of shapes and sizes. Past the orchard, is a plot of even more elaborate design—a series of snow-encrusted shrubs cut into the forms of stars, circles, and squares. Since I know this Tycho is no king, I wonder again whether he is a sorcerer to have conjured such an intricate universe.

This impression is only heightened when we pass a circular formation of wooden palings and enter a round clearing, in the center of which lies Uraniborg castle. Atop the highest spire, seeming to fly up into the darkening sky, is a rotating statue of Pegasus, the horse’s wings spread as it spins in the cold breeze. Beneath this lies a limestone crown of domes and cupolas. The turrets that reminded me of ladies’ skirts now seem even more fantastical as they appear to be attached to the sides of the castle’s red brick hull by little more than slender poles. Reclining above the door is a statue of a half-naked Titan resting his hand on a globe of the earth and looking to the heavens.

Even Matheus stops to gaze upon the palace in wonderment. I forget my fears and join him until, from the side of the castle, I hear a cacophony of birdsong, a tangle of chirps and whistles and caws. It seems that my new master keeps an aviary, and the birds’ wild tune returns me to my sorrows. For the singing of the trapped creatures reminds me of Lia and how, because of my actions, her voice is absent from the world’s song.

It is with heavy heart that I follow the servant boy under the statue of the Titan and into a long hall illuminated by torches. I expect it to lead to the sorcerer’s room, a study exhibiting the same misplaced faith in order as the rest of Urania’s kingdom. But what I see instead is so miraculous that I blink several times to be certain I am not dreaming. In the center of a rotunda at the end of the hall is a large bronze fountain with the heads of the four winds arranged at equidistant points around the basin. But more extraordinary than the fountain itself is the water spraying out of the winds’ howling mouths.

Uraniborg, colored woodcut from Tycho Brahe’s Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598). Wikimedia Commons

“How the devil … ?” Matheus says before he catches himself.

I am just as perplexed. Even at Coudenberg there was no such thing as water that ran indoors, never mind a fountain that sprayed water inside in the dead of winter. I stare at the winds, trying to figure out where the water is coming from.

The servant boy watches us, all but ignoring the magic fountain.

Matheus looks uneasily around the rotunda, fingering his lucky copper. Judging from the identical halls that depart around us on all sides, we stand at the very heart of the castle. Adding to the eeriness, there is not a single soul in sight.

“I have business with Lord Tycho,” he says to the boy, his voice commanding but his eyes darting from side to side. “I demand to see him.”

The boy points to the fountain and holds up his hands—gesturing for us to stay where we are, then disappears down one of the corridors and through a door. Matheus paces, staring at the fountain, then turns on his heels and walks nearly the length of the hall we first entered, as if contemplating his own escape. While he does this, I walk up to the magic fountain and hoist myself over the basin. I dip a finger in the burbling water and feel a stab of longing for Lia. She would have loved this fountain, this tiny sea, its mist of spray.

Footsteps sound behind me and I hastily lower myself back to the ground. The servant boy gestures for us to follow him down a hallway that lies perpendicular to the one we first came through. When he comes to the end, he opens a massive wooden door.

The scene that I behold is even more wondrous to me than the fountain we have just left. Inside this circular room, a dozen men labor by the blazing light of candelabras, oblivious to our entrance. Some study a brass globe as large as a bale of hay that rests on a base by the far window; others hunch over wooden desks, their quills dancing; still others search a vast library. For the first time since Lia’s death, I feel my spirits rise. The shelves are lined with hundreds of volumes of every size and variety. Even the Infanta did not possess so extensive a collection.

I gradually become aware of other curiosities as well—a life-sized metal man and lion stand at attention to the side of the door. Music plays, though I see no musicians. But it is the books to which my gaze returns. I wonder if some of these volumes are devoted to whatever dark arts allows water and music to appear out of thin air. Most of all, I hope that I, too, will be permitted to study them.

A barrel-chested man with a white ruff about his neck breaks away from the group gathered around the globe and marches toward us. His reddish blond hair and beard are mixed with gray, a scar bisects his forehead, and a more frightful detail—part of his nose seems not to be pink, like the rest of his round face, but reddish brown.

“Lord Tycho Brahe?” asks Matheus tentatively.

I have no doubt that, although he does not acknowledge his name, the man who glares at us is Tycho. “No one is supposed to interrupt us until supper,” he grumbles in Dutch. “We are working.”

“We have come all the way from Coudenberg,” says Matheus.

Tycho barely seems to register this defense. Instead he peers down at me. As he does, I get a closer look at his nose and realize that the reddish brown part—the entire upper half—is actually made of copper.

“Another dwarf?” he says wearily as I try not to stare back in horror.

“I have a letter,” says Matheus, as if this explains all.

Tycho impatiently reaches out a hand as Matheus fumbles for the letter. Upon finally securing it, Tycho tears open the seal and glances at it hastily. “Fine. Fine. Let’s proceed.” Switching to a tongue I recognize as Latin, he shouts, “Longomontanus, Severinus, come here!”

Two young men obediently rise from the tables. The first to reach us is a tall youth with a head of golden curls and long limbs that seem to amplify the brevity of my own. From the confidence of his step and the easy smile upon his face, I wonder if he is Tycho’s son. Following in his wake is a smaller fellow with a servant’s watchful eyes and a scraggly beard.

“Severinus, paper,” Tycho says.

To my surprise, it is the tall youth who plays the servant, loping off to fetch paper and quills and sharing them with the smaller man.

“Dwarf jester,” Tycho dictates to them. “Six-year minimum. No library access or scholarship privileges. No notes or letters to the outside. No revealing any aspect of our pursuits at Uraniborg.”

I am certain my new master assumes that I am unable to follow this ancient tongue. But I do, and the portrait of indenture he paints fills me with despair. My position upon this sorcerer’s rock is no different than at Coudenberg. I am once again a “dwarf jester,” a plaything of the powerful, a fool whose task is not to study or learn but to amuse those around me. I am barred from this magnificent library, and the books and learning that could have sped the progression of six slow years. To make matters worse, I am not even permitted to correspond with my mother and Willem, who must be wracked with worry over my long silence. I cannot live such a life. I resolve to find a way to escape and return home to Astraveld.

The scribe with the scraggly beard, Longomontanus, crouches down before me and holds out the paper upon which the terms of my service are written and a quill. Blemishes dot his pallid forehead, and his teeth are yellow.

“What is your name?” he asks in Dutch.

“Jepp,” I say.

“Can you write, Jepp?”

“Just have him mark the contract with a line,” Tycho says impatiently in Latin.

I am tempted to answer my new master in Latin, to tell him that not only can I write, but that I understand his every word and care not for the servitude and hard conditions of my employment. But I have little faith that such a revelation would alter my fate. I am certain that these men, like the courtiers at Coudenberg, are capable of seeing me as little more than an amusement. Better that I play the fool so that they do not suspect I have the cunning and intelligence to escape. Still, I hesitate, for I do not wish to legitimate this devilish contract.

“Time is wasting,” Tycho says in Dutch.

“Perhaps he can read Latin?” the handsome youth, Severinus, says in Latin then grins.

I hastily mark the contract in a rude hand, not wishing the others to guess how Severinus’s jest approaches the truth. Longomontanus takes back the quill and folds up the contract.

Tycho hands Severinus the letter that heralded my arrival. “Put that with my correspondence,” he says in Latin.

Then he swings around and points to Matheus who is staring at the enormous globe. “And get this man out of my house!”

Just as he says this, something shiny flies past me and lands with a clatter on the floor. Matheus begins to back out of the room and when I look up, I can see why. My new master has lost part of his nose. The top, from the middle to the bridge betwixt his eyes, is a gaping hole. However, no one but Matheus seems aggrieved by this, including Tycho himself. He merely sighs as if a crumbling nose is his lot in life.

“Jepp, your labors start now,” he says to me in Dutch. “Pick up my nose.”

I never thought I would look back fondly to the days of donning the costume of a beast or being baked into a pie. But retrieving a man’s nose is a far less savory business. As I squat down to scoop up the copper proboscis, Matheus says, “Goodbye, Jepp. Good luck to you.”

I can tell from the pitying look in his eyes that he means it. Unexpectedly, tears well up in my own. Matheus has been my jailor but, faced with the uncertain cruelties of my new home, the memories of his small acts of kindness loom large. I wish not for him to go.

“Goodbye, Matheus,” I say.

He reaches out his rough hand and gently pats my shoulder. Then he turns and follows the servant boy to freedom.

As the door closes behind him, I pass the copper nose up to Tycho. He procures a small box from his vest pocket, dabs some ointment from it onto the back of his nose and affixes it to his face. When he seems satisfied that it will hold, he releases his grip on it.

“You are not to come in here again,” he says. “Jonas will help you prepare for supper, where you will entertain us.”

A few minutes later, a burly valet with a curly thatch of yellow hair opens the door. Tycho issues him instructions in Danish, then peers down his copper nose at me and adds in Dutch, “There is a particular task, Jepp, I believe you well suited for.”

With this my master smiles, and I am left to wonder what new misery awaits me and how quickly I can devise my escape.

Jonas silently leads me back into the hall. Near the base of the fountain, I spot a bent copper and hastily snatch it up. In his fear and confusion, Matheus must have dropped it. But it is too late to return it to him now, besides which I need its auspicious tidings even more than he. Although the water continues to flow from its magical source, there is still not a single soul in sight. But, just as we pass the fountain, I hear hoof-like clops on the marble floor. I tell myself that someone must have ridden a horse into the castle although why Tycho would allow a beast inside to soil his floors and guzzle from his bronze fountain is a mystery. When I listen more closely, however, the clops sound more delicate than that of a horse as if its hoof is cloven and I wonder if what I am hearing could be human or even, in this mad castle, a mix between beast and man.

This mystery, like the invisible music and flowing water, is left unsolved as Jonas ushers me down the hall and through a door at the end of it. To my relief, this room is nothing stranger than a kitchen. Flavorful clouds of steam hover in the air and fish and game of numerous sizes and shapes lie on a large wooden table, waiting for the cook’s alchemy of fire and spice. The cook, a large man with cheeks so round they look as if they have been stuffed with apples, shouts orders at a bevy of women. He greets me with but a brief look as if, not being hare or goose or boar, I am of little interest to him. But several of the women allow their eyes to linger, their red faces giving them the appearance of being stewed along with their dishes.

Jonas says something in Danish but all I can make out is my name, Jepp, which the women repeat softly over their pots and dough like an incantation. I notice their straw-filled pallets stacked in one corner of the kitchen and I hope that I will be stowed along with them in this warm and savory realm. I imagine growing plump in my melancholy, a creature of appetite whose loneliness and grief is dulled by his gut.

But, to my regret, Jonas leads me into a chamber dim and chilly by comparison. Although pallets cover nearly the entire floor, proof of an invisible army of servants, not a single soul inhabits the shadows. As Jonas searches through a sack left atop one of the pallets, I cannot help but think of Lia’s song—of love left on a distant shore, of silent seas, and being held captive—and how it has become my own. I run my fingers along the spiny seashell in my pocket.

A short while later, Jonas finds what he is searching for—a many-pointed cap that jingles with bells. At the sight of it, my despair deepens, for it confirms that I am yet again expected to humiliate myself for the pleasure of the rich and powerful. But I fear what will happen to me if I openly resist and, as he gestures for me to do, I put it on.

We sit silently side by side in the darkening gloom until a knock sounds. At this signal, Jonas leads me back into the blazing hall where we stop before a door next to the forbidden library. A great din of voices and tongues issues from inside as if Tycho has transformed the birds in his aviary to human form. Jonas opens the door wide and pushes me through.

The room before me is generous in its proportions and richly appointed—in one corner is a towering tile stove, in another a curtained four-post bed where Tycho and his wife must sleep. In the center of the room, is a sideboard laden with silver vessels for drink, all of them engraved with the same coat of arms. But it is a long oaken table against the far wall that commands my attention. Sitting on benches on the far side of it are at least forty souls, chattering with vigor as the cook’s labors lie steaming before them—a slab of what looks to be venison drenched in sauce, a whole fish, a tureen of stew, a side of rare beef, a platter of tongue, chicken, eggs and eel, and heaps of sugar cakes.

Lording over this feast, on a seat higher than the others, is my new master, his copper nose glinting in the candlelight. A plump, flaxen-haired woman sits on the elevated perch beside him and a gaggle of fair-haired children flank him—ranging in age from shrieking infant with nurse to noisy young woman banging her fist on the table upon some point. I am relieved for their sake to see that all of them have inherited their mother’s sturdy, upturned nose.

“Jepp,” Tycho says, waving a tankard in the air. Then he says something in Danish and his company bursts into laughter. I steel myself for more insults.

One man pipes up and then another follows but both speak Danish and the only words I catch in common are “per gek.” But whatever the men have said, Tycho seems little amused by it. He grimaces and shakes his head. Then he points at me.

“Under the table,” he says in Dutch.

I wonder if I have misheard him or whether he has made a slip in a foreign tongue. Surely, he wants me to sit at the table, not under it. I walk hesitantly to the edge of it, the smells of the banquet making my stomach tighten.

“Now under!” says Tycho impatiently.

I stoop beneath the edge, expecting him to stop me. But he does no such thing. A long, straight finger descends under the table and points to his black leather shoes.

“Sit at my feet,” he says.

I wonder if this is the task he has envisioned me well suited for. I can hardly stomach the indignity of this arrangement but I cannot betray my strong will, besides which Don’s bruises are but newly healed and I fear the price of disobedience. As I crouch at my master’s feet, I feel as if he has transformed me into a hound. Above, there are delicacies, laughter, the company of men, while below I quiver, my gut rumbling. This impression is only strengthened when Tycho’s ringed hand slides under the table with a morsel of venison. As he waves it before my face, I realize I am meant to take it. I briefly consider refusing but my hunger triumphs over my pride and I snatch it from his hand. My obedience is rewarded with another morsel—a slice of eel.

As I chew it, I hear a tankard pound the table above my head.

“A few words on the great work of Uraniborg!” Tycho says in Latin.

Though I dare not bite my master’s hand, I can at least take satisfaction in eavesdropping on his labors, which he seems so eager to keep secret from the world. Perhaps I will even glean some intelligence that will aid in my escape.

“Severinus, please share our most recent progress.”

I see a pair of long feet shift as their owner rises. “Thank you, my lord,” says Severinus in a voice nearly as bold as his master’s. “As of this day, we have collected 793 stars.”

The table thunders above me as fists pound it in applause. But I am perplexed. How does one collect a star? I imagine Tycho’s army of scholars flying through the sky with nets. I wonder where Tycho stores all these stars, and whether it is they that power Uraniborg’s magical fountain and fill his study with music.

“This is work well done.” Tycho says when the applause dies down. “But we must hasten our efforts while maintaining the precise standards that Urania has set for us. To a thousand stars!”

“A thousand stars!” echoes the table. Their cheer is so rousing that if Tycho’s nose had not tumbled off and clattered to the floor in front of me, I might have forgotten myself and joined in. I pick it up just as an empty palm impatiently appears before me, and in a strange reverse of our eating ritual, I drop the nose into it. I can see Tycho’s other hand dig into his pocket for his box of ointment.

A moment later, when the nose is doubtlessly back in place, Tycho bangs his tankard yet again.

“To celebrate our continued progress, my new dwarf, Jepp, will amuse us,” he says in Latin.

I feel the toe of a shoe drive into my back and I crawl out from under the table. Forty pairs of eyes watch me expectantly as I stand beside my new master.

“Well?” thunders Tycho. “What can you do?”

My true talent is books and languages. But this I will never reveal and, thankfully, Lia has given me another.

“I can dance.”

“Jacob!” Tycho says.

A dark-haired lutenist appears and strikes up a lively melody. Though I have not danced since Lia’s death, I am relieved to discover that my feet remember what my mind cannot. But I take little pleasure in the applause and cheers that follow my performance. For I think only of Lia and how it pains me to perform the French dance without her.

Tycho laughs heartily as I bow. “What a sight!” he says in Latin.

He hands me an oyster and sends me back under the table.

Jacob begins to play a ballad and for a brief moment, I imagine that Lia has been brought back to life by the magic of Tycho’s 793 stars. But Jacob’s song is long and far less beautiful than Lia’s. Tycho continues to proffer me tidbits, which by the lengthy ballad’s end leave me feeling as if I have actually consumed a meal. Still, each bite fills me with shame and, as Jacob plucks the final strings of his song and servants appear to take away the dishes, I pray that the banquet is over and Tycho will release me. But as more servants appear and more savory smells fill the room, I realize that the supper is merely beginning. Above I can hear the splash and fizzle of ale and wine being poured, the thunderous laughter of my master, the clatter of silverware. A bite of roast lamb with beets is handed to me under the table, then a few crumbs of almond tart. One of the scholars recites a poem he composed on the glories of the heavens later another man sings.

As the voices above grow louder and merrier with drink, Tycho’s children race wildly around the table. A boy of perhaps five, though no taller than I, with a round face and wispy blond hair, dodges under the table and sticks his tongue out at me before he is hauled back out of my realm by an invisible hand. Then a second face appears, that of the young woman whom I had first seen banging her fist on the table. That she is in so indecorous a position, crouched on her knees, seems to cause her no shame though her form is most womanly. Her round face hangs over me like a moon, cratered by a few white smallpox scars. She appraises me with a bold, unapologetic stare then says something in Danish.

“You don’t speak our language,” she says in Latin when I fail to respond.

I almost shake my head in reply before I stop myself. I have never heard a woman speak this ancient tongue though it surprises me not that a sorcerer’s daughter would have this skill. Why she thinks I possess it, however, strikes me as most curious.

“My name is Magdalene,” she continues in Latin. “I am sorry on my brother’s behalf.”

Though I wish to acknowledge her, I instead hold up my hands and smile foolishly as if to indicate I do not understand. Magdalene shrugs as if I no longer warrant her interest and disappears.

Before I can make head or tails of this odd conversation, the door opens and I hear the strange clopping sound of the creature I heard earlier. Merry shouts issue from the table, Tycho’s loudest of all, as I behold four brown legs, moving with the wobbly motion of a man on stilts. As I peer out from beneath the table, I can see Jonas lead in the rest of the creature, a massive mix of horse and cow. Enormous antlers, like the bones of an angel’s wings, rest atop its head and a brown wattle-like beard hangs down from its neck.

Upon reaching the table, it bellows pitifully. Then the bellowing abruptly stops, replaced by wet, slopping sounds and the occasional snort. I crawl out from beneath the table and peek over the edge. To the delight of Tycho and his boisterous company, the beast is muzzle deep in a tankard of ale.

“Jepp!” Tycho says, as if recalling my presence. His nose, I notice, is not properly affixed but tipped to one side. He draws himself up in his chair as if to make some grand declaration and I wonder if he means to reprimand me for abandoning my post.

“This is Ulf,” he says in Dutch. “My moose. He is tame and exceedingly partial to a draught of ale.”

Though I would not have been surprised if the creature had turned to me and issued a proper Latin greeting, Ulf takes no notice of our introduction. He instead clatters the tankard against the table in his efforts to devour its dregs.

Tycho’s nose loosens further as he leans toward me. “The great disadvantage to Ulf’s appetites is that on occasion he has broken free and wandered the halls in an inebriated state. This is quite dangerous for him. But you, Jepp, can prevent that! As his bedmate!”

I smile wanly, certain that my new master is playing some trick upon me for his amusement.

“It is good fortune indeed that you were sent to us,” Tycho concludes. “Now you and Ulf may retire for the night.”

Pulling a rope around Ulf’s neck, Jonas tries to lead him away from the table, but the moose—its muzzle still wedged in the tankard—won’t budge. Clearly this is not the first time Jonas has met with such obstinate behavior for he next takes the tankard with him, using it to entice the beast forward. The moose belches, filling the air with the smell of hops, and stumbles after it.

Tycho gestures for me to follow him, which I do at a safe distance. Even though my master waves as though he does not expect to see me again, I wager that this is but a jest and Jonas will send me back as soon as the moose is secured in its stable.

But the room to which he leads Ulf is no stable but a small, door-less chamber off the kitchen covered with straw and reeking of animal fur and dung. Jonas ties the creature to a post on the wall. Ulf guzzles from a small basin into which flows another mysterious stream of water whilst Jonas sets a straw-filled tick on the floor, tossing a coarse blanket atop it. It is only then that I realize that Tycho fully intends for me to sleep with this creature. Jonas points to the pallet and then to me, confirming this impression, as he departs.

After studying it for some time, I conclude that the pallet is just far enough away that so long as Ulf does not break his tether and embark on one of his drunken nocturnal gambols, I should escape being trampled. This gives me little comfort, however, as I lie on the pallet and stare at Ulf’s massive rump. Tycho is most certainly another cruel and capricious master. I take out Matheus’s bent copper and rub it between my fingers as he did. I cannot accept that this—a life of ignominy, loneliness, and loss—is what fate intends for me.

When at last I fall asleep, I dream Lia and I are trying to escape this diabolical island, chased through the night by Tycho’s stars.