The Woman in Green: A Chinese Ghost Tale from Mao to Ming, 1981-1381

1981

The film begins on a darkened set, billowing with fog, echoing with a woman’s cry to the heavens. Her figure comes into view and she zigs and zags across the screen, her diaphanous white robe glittering with silver fringe. Long sleeves accentuate her swirling, flowing movements, the special mark of Chinese opera singers portraying ghost characters.

From the distance of three decades, it’s hard to understand why the 1981 film Li Huiniang was so popular with Chinese audiences. The shape of the film’s story was familiar, true: a ghost tale told in China for six hundred years or more. But to contemporary eyes, its surface now seems crowded and cheapened by the special effects that the Shanghai film studio piled onto it. Fog, flashbacks, and visual tricks made literal what earlier versions of Li Huiniang, a traditional Chinese opera, had often left to the imagination. However, there is no doubt that the story of a tragic Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) concubine, the titular Li Huiniang, who returns from the dead after being unjustly slain by a corrupt prime minister, still found favor with audiences. This was a haunting ghost.

Past productions of Li Huiniang, at least in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), had always been performed onstage, without the aid of special effects. Actors made do with elaborate costumes, fire breathing, colorful face paint, and spectacular acrobatics. Traditional Chinese theatre is austere to the extreme: outside of the exquisite costumes and elaborate makeup, stages are bare, and a set of conventions replace props and sets. Often, the audience is expected to conjure the particulars of a scene in their heads. Actresses gesture to empty stages while singing of lush gardens and gilded pavilions. The horse a general rides is symbolized by a fringed horsehair whip. One set of table and chairs can set a thousand scenes. It is a world away from movie sets, multiple takes and fog machines.

In spite of those differences—and perhaps because of them—Li Huiniang took Chinese screens by storm. In this new celluloid version, the actress Hu Zhifeng, playing the title character, danced, sang, and posed her way through effects that rippled around her. Hu’s performance has aged beautifully, and it’s tempting to pin the film’s success on her star-turn, and not the audience’s excitement at an old story made new.

To do so, though, ignores the story itself and the ghost that Hu Zhifeng portrayed: Li Huiniang. Hers was a story that had been worked and reworked since the fourteenth century. There was something about this tale of a concubine, unjustly slain by a corrupt prime minister, which appealed to audiences over centuries. In the early 1980s, however, her allure may have rested in her past of the last twenty years. Li Huiniang was more than just China’s glittering literary and dramatic history. The story’s triumphant return embodied the hope that other more recent specters of the past were dead and gone.

1980

For most of us, ghosts are little more than paper cutouts trotted out in October, or stories told around an isolated campfire. They are memories of childhood frights and bogeymen lurking in closets at bedtime. They are things without substance.

They have been a far more adult matter throughout Chinese history, however. Tales centered on ghosts are treasured within the Chinese literary canon, and some of the most beloved operas feature ghosts, come back to warn the living, find love, or exact vengeance. Sometimes, they are the shades of young women who have died for want of a dream lover. Other times, they are avenging spirits of men cut down in their prime. They may be restless souls, hungry ghosts who have no descendants to offer them the appropriate rites. And with the ascension of the Communist Party in 1949, ghosts became an even more serious affair: feudal holdovers and literary traditions to be stamped out with all possible haste.

In 1980, a woman named Meng Jian recalled the pain of standing in front of her father’s ashes. Writing a postscript to the republication of a play written by her father, Meng Chao (1902-1976), she poured out her rage. She directed her internal fury not at Mao Zedong or his wife, Jiang Qing—one of the faces of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution that had plunged China into years of chaos and upheaval. Instead, she cursed Li Huiniang, the concubine her father had reinterpreted. The cries of a grieving daughter echoed the cries of the ghost she cursed. “It’s all because of wanting to write you, having written you that it’s come to such an end. You are an ancient, immortal ghost—you can become a celestial immortal, but my father is a new ghost, and that fact is extremely hard to swallow, it is an extraordinary injustice!”

1976

Unlike literary ghosts, most people die in far more pedestrian circumstances. Meng Jiang’s father, Meng Chao, a good old revolutionary with reasonably impressive literary and party credentials, died alone in a small Beijing flat, according to some stories. His old friend Lou Shiyi, a well-known essayist, wrote in 1979 of his friend’s last days:

Meng Chao was all alone, and he had to ask an old granny in the hutong to cook for him. I went to go see him when I had time—he was alone, reading Selected Works of Chairman Mao. All of his books had been confiscated, only this one book was left. Sometimes, he’d lean on his walking stick and come to my house to borrow novels … Some days after he had come to borrow a volume of [Nikolai] Gogol’s writings, I heard suddenly that Meng Chao had died. They didn’t say what big illness he’d had. The hutong granny who cooked him food knocked on his door early in the morning; when he didn’t answer, she had to open the door and go in. She looked, and Meng Chao was lying on his bed, blood trickling from his nose, dead. At that time, the ‘Gang of Four’ [Jiang Qing’s clique] was still in power,so several friends had to carry his remains on their shoulders to take him to be cremated—in the end, he never got to see the ‘Gang of Four’ fall from power; he just wore his [bad element] cap and ‘went to see Marx.’

His daughter claimed that her father’s last words to her were “The injustice!” It was just one death of many, and a reasonably peaceful one at that. But how had it come to this? Why did Meng Chao, a dedicated party member of over forty years, die a lonely death in a Beijing apartment, crying that he had been wronged? How had he died “wearing a bad element cap,” suffering in the shadow of being branded a niugui-sheshen—an ox ghost-snake spirit, the worst of the very worst?

There are many beautiful women in historical tales who are swept up in the midst of great events. Helen of Troy “launched a thousand ships.” The Tang consort Yang Guifei was blamed for a rebellion. Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church for his bewitching Anne Boleyn. Mao had Jiang Qing, his wife who stepped into political prominence in 1964, after years of being excluded from the political stage. And then there was Meng Chao’s—beautiful Li Huiniang, with the blood-stained face. She was the ghost whose downfall, along with Meng Chao, marked the beginning of Mao’s last great assault on his party.

1965-1969

In writing of the Cultural Revolution, most historians—as well as many participants—mark its “prelude” as the November 1965 publication of an essay criticizing a famous drama (also published in 1961) called Hai Rui Dismissed from Office. The play, written by the deputy-mayor of Beijing, was based on the true story of one upright official of the late Ming dynasty (1368-1644). The essay criticizing it, carefully orchestrated by Jiang Qing and other radicals, may have led to the formal launch of the Cultural Revolution, but it was hardly the first spark. That honor belonged to Meng Chao and his lovely ghost, Li Huiniang, the kindling that allowed those early fires to burn so brightly. In the first six months of 1965, it was in fact Meng Chao and his ghost who faced severe criticism in the pages of leading journals and papers. Li Huiniang had faced the ire of cultural radicals since 1963, even inspiring a ban on portraying ghosts in theater—the harbinger of the PRC’s swiftly increasing radicalization of culture and politics.

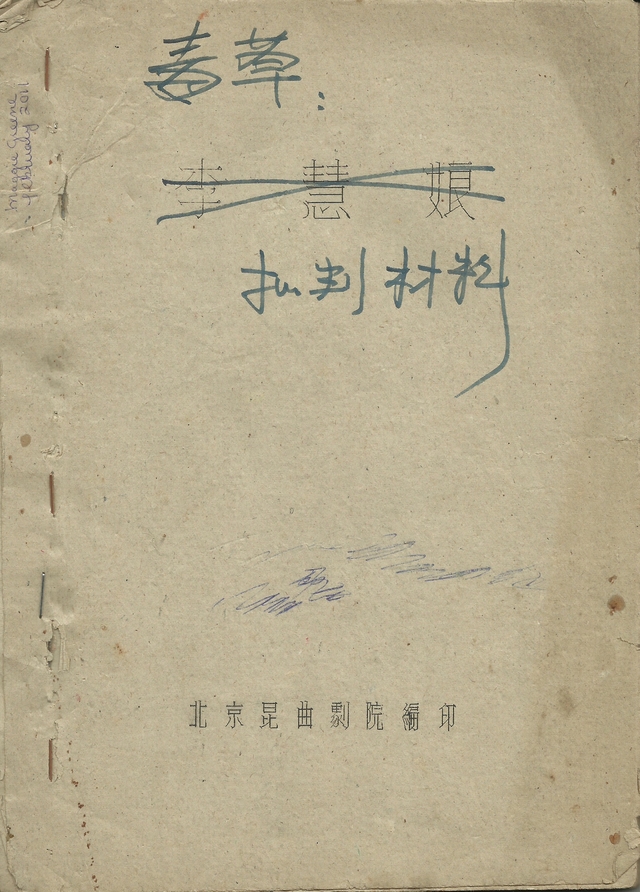

A copy of the script of Meng’s Li Huiniang, its title crossed out. Instead it reads “poisonous weed” and “material for criticism.”

What harm could there be in telling the tale of a ghost, or of an upright official? The cultural radicals, ready to remake the party in their own image by tearing the establishment down, claimed that the plays proved their authors’ bourgeois spirit, their individualist leanings, their anti-party, anti-socialist thoughts. They were poisonous weeds, evidence of the sickness the Chinese Communist Party still harbored, a sickness that needed to be excised as quickly as possible, by any means necessary. Historical settings were dangerous, for it was never “history for history’s sake,” as men like Wu Han liked to claim. There was a long tradition in China of indirect remonstrance, the use of historical parables to criticize an emperor or high official. It was clear, or so claimed the essays attacking Meng Chao, Wu Han, and the dramatist Tian Han, that these authors, senior members of the intellectual establishment, were using their significant literary and academic chops to bring about their own bourgeois, capitalist goals. They were class enemies, and they were not people, but ox ghosts-snake spirits.

And so the writer of a ghost became a ghost himself. The essayist Lou Shiyi wrote that the period preceding the formal declaration of the Cultural Revolution was a time of great anxiety for everyone. “For a short while, a ghostly atmosphere flickered, and we saw ghosts everywhere. Everyone was afraid of ghosts, deathly afraid.” Meng Chao himself was certainly very frightened, and had good reason to be.

By many measures, the fact that Meng Chao died alone in a Beijing hutong, blood trickling from his nose, was “lucky.” Compared to friends who had been publicly humiliated, thrown in prison, and left to die, a quiet death at home was perhaps a more fortunate death.

It was not the fate Meng Chao wanted for himself, however. In the late 1960s, he attempted suicide. Though rushed to the hospital, the doctors refused to treat him until the officials handling his case arrived. The question the doctors asked was simple: “Is this a person you want or not?” The handlers responded: “This person is a big traitor, and you mustn’t allow him to die!” At which point treatment commenced.

1961

Four years before the first serious criticisms of his work—a universe away in the Mao years—Meng Chao was the toast of Beijing’s artistic world. Li Huiniang premiered to high praise from all quarters, charming the intellectual and political elite of the day. At the Northern Kun Opera troupe premiere, another senior writer turned to Lou Shiyi and said of Meng Chao, “Look at that, an old tree starting to bloom.”

The Li Huiniang that stepped out on the Beijing stage that day must have been every bit as dazzling as Hu Zhifeng’s film extravaganza. The audience would have sympathized with the lovely concubine of the prime minister Jia Sidao, killed for a few quiet words uttered in admiration of the handsome young scholar Pei Yu—‘What a courageous youth! What a handsome youth!’ And they surely must have appreciated her strength of character, her bravery after death. Instead of thinking only of herself, she worried over the fate of China’s people, suffering under the policies of Jia Sidao. She was going to be a “ghost bodhisattva,” come to offer succor to a suffering people. The overwhelmingly positive reaction to the play must have delighted a man who had skirted at the edges of fame, but had never truly been a literary star.

The script was a lovely throwback to the great Chinese dramas of centuries past. Its language is exquisitely literary, showing off the author’s grasp of and appreciation for what many intellectuals and artists described as their “inheritance.” In the script itself, there is no pretense of being aimed at the proletariat, the workers, peasants, and soldiers that Mao (and Lenin before him) had declared to be artists’ true audience. The play’s prologue, a common feature for traditional drama, laid out Meng Chao’s intellectual interests and the bare outlines of the plot:

Crossing the river to the south, the mountains are rugged,

The dissolute still hold sway in Lin’an.

In a bamboo hut, I am fond of reading ‘discourses on ghosts,’

My intentions and energy link to a long rainbow,

My vigorous brush punishes treacherous officials.

Drawing from the wisdom of my predecessors,

I express my own humble views,

And give the old play Red Plum a new turn.

I have carefully studied the tender emotions of youths, the feelings of personal enmity.

I write of a flourishing dream being cut off,

I write of northern horses neighing at the banks of the Qiantang.

Jia Sidao endangers the state and harms the people, but there is music and song at evening banquets;

His smile hides a dagger, and a chance for murder appears;

Pei Shunqing, indignant, speaks bluntly—the source of his misfortune,

Pleasing the hearts of people, extending righteous justice,

Li Huiniang is a heroic spirit after death, avenging injustice!

For Mao’s China, however, such opening notes were provocative. Meng Chao styles himself as a solitary scholar of the type found in famous classical poems, hardly an image we associate with socialist art. And he writes of the waning days of the Song dynasty, imperial scholars and enslaved beauties—subject matter far from Mao’s pronouncements on art. The play hinted that ghosts, emperors, and scholars were appropriate artistic subjects for a socialist society.

Meng Chao and others took the issue seriously, debating in journals and newspapers, and writing scripts and novels and poems. 1961 was an unusually open period. Mao Zedong was in retreat, the country was stabilizing, and artistic politics were less extreme—a space in which senior, liberal intellectuals and politicians could enjoy classical culture. Taking that chance, Li Huiniang was a clear declaration that classical works and classical language still had purpose and relevance. Art was not—and should not—be about destroying a creative tradition, no matter how lacking in revolutionary credentials it may have been. Meng Chao was reaching back to what he and others saw as their birthright.

Yet the Li Huiniang that he imagined became a fierce woman warrior after death, demanding justice not simply for her own humiliating end at the hands of Jia Sidao, but for the people—the People—he was hurting. Taken generously, it was as if Meng Chao was suggesting that China’s cultural birthright was still compatible with socialism.

But why a ghost? Why this ancient ghost? Why Li Huiniang? And what other lurking ghosts, new ghosts, hungry ghosts was she avenging?

1959

There is a much-loved plot structure in Chinese drama, one put to great use by countless authors over the centuries, particularly in times of trouble. It goes something like this:

It is a time of great crisis for China, a period when peasants break under the strain of government pressure and foreign armies agitate on the borders. A cruel or impressively incompetent ruler is in power, a person who cares for little but his own pleasure. At best, he ignores pressing political issues and the unhappiness of his people; at worst, he makes the lives of the people worse through draconian punishments and inhuman land requisitions and taxation. Weak and corrupt lackeys and subordinates surround him. But there is somebody—there is always at least one person—who finally stands up to him. It may be an official with a sharply honed sense of right and wrong, or perhaps a gutsy young scholar who burns with righteous fury. And sometimes there is an innocent bystander who meets a gruesome, unjust end.

Senior intellectuals in China found sudden inspiration in such classical tales after the party leadership scripted a crisis of still more tragic proportions. In 1957, Mao Zedong announced that the PRC would overtake the United Kingdom in steel production within fifteen years. The Great Leap Forward was to be a leap not just into industrialization and collectivization, but towards superiority in all areas of life, including the realms of science, literature and art. This was a tall order, and Mao needed more than factories for it to come true: he needed capital, and lots of it. As was so often the case, the vision was built on the peasant’s back, through the sale of grain on international markets.

The Leap began in 1958. It immediately fell into exuberance and sheer fantasy. Local cadres over-reported harvests to their higher ups, who then reported slightly more inflated numbers to their higher ups. And so it went, all the way to the very top, to the Central Party who received hugely inflated numbers about the amount of grain available. It was a twist that the old playwrights never dreamed of: when the state came to take their grossly estimated “fair share” of the harvest, they wound up taking all the reserves—and in many cases, most of the grain the peasants needed merely to survive. It was a man-made, policy-driven famine of terrible, shocking scale.

Over the course of the Leap, upwards of thirty million people died, many due to starvation. Farmers lay down in the fields of their collectives to die, too hungry and exhausted to continue living. Even those who were safely shielded from the brunt of the famine remember the taste of “bread” that was not made of grains, but of ground-up bits of leaves, sticks, or whatever could be found. A cabinet member was dismissed and humiliated for suggesting that the peasants were suffering and the policies needed revision.

In the fall of 1959, as the true horror of the Leap was unfolding, Meng Chao was ill and confined to bed. From his privileged position in Beijing, he took in the cool night air, listened to the mournful cries of insects, and cast his mind into the past. He found himself thinking of a ghost play he had seen as a child, with a beautiful character named Li Huiniang. That character had suffered at the hands of Jia Sidao, and had met an unjust end, returning as a ghost to protect a handsome young scholar. This story wasn’t unexplored in modern China; four years before, a fellow playwright attempted to update the story of Li Huiniang, to make her hew to socialist literary theories by removing its “backward” peasant superstitions: to the horror of his fellow playwrights, he had removed the ghost from the ghost story.

But Meng Chao envisioned something different: a twist on a classic, not a simple socialist revision. She would have more of a purpose than a mere love affair. If ever there was a time for cosmic justice, for vengeance from beyond the grave—for succor from beyond for the living—surely it was a year when millions of people became hungry ghosts?

1912

In the waning years of the Qing dynasty—or perhaps the first few years after the declaration of the Republic—a boy from a prominent family watched plays when theatre troupes passed through his hometown of Zhucheng in Shandong province. Young Xianqi likely had no inkling of the momentous changes that had swept away the natural path his life was supposed to take, that of the scholar-official. It would have been a life of studying, exams, and civil service. It was a path his father had followed, and his father before him, and his father before him. But even in a period where the future was ever uncertain, coming from a relatively wealthy, intellectual family still had its advantages. No matter what the future held, he would have a foundation in the classics, a good education, and an appreciation for China’s literary past that would grow with time into mastery.

But for now, he crowded close to the front of temporary stages, enthralled by the sight of his favorite literary heroes and villains standing before him in flesh, blood, and bright silks. He had one in particular he loved, a ghost clad in white robes with a silver fringe. They swirled and fluttered around her feet as she seemed to float on the stage, and a red ribbon attached to her glittering headdress represented her violent death. She sang of an unjust life and her love for a living scholar. She was beautiful beyond belief.

Long after he took a pen name—like so many Chinese intellectuals before him—and threw himself into working for a socialist future, he would remember that ghost from his childhood. It was so dazzling a memory that she reappeared to him in the cool autumn of 1959; but also so fleeting that it might as well have been centuries ago.

1600

The reign of the Wanli emperor (1572-1620) was not exactly a bright spot in the history of the Ming dynasty. There were wars and rebellions, increasingly powerful eunuchs, warring factions of Confucian officials, and a growing threat from the Jurchens of Manchuria. It was hardly a situation that a largely unmotivated emperor—possibly a heavy user of opium—was capable of handling.

The shadow of this crumbling dynasty was particularly productive for drama, however. It was a heyday of chuanqi, “marvelous tales,” stories of ghosts and dreams and gods and all manner of spectacular subjects, lifeblood of one of the most celebrated works of Chinese literature, Tang Xianzu’s The Peony Pavilion.

The writer Zhou Chaojun never reached the level of Tang, a true master, but he put to paper his own ghostly tale, called The Story of Red Plums. Like many Ming dramas, it was highly self-indulgent—lengthy, confusing, with plot upon plot upon subplot—but its core was a compelling tale of a corrupt ruler, a great crisis, and a love story or two. A young scholar named Pei Yu criticizes the prime minister, Jia Sidao. A concubine named Li Huiniang murmurs a word of appreciation for the young scholar’s good looks, and for this she is killed. Pei Yu faces the full wrath of Jia Sidao, but Li Huiniang—tied to the mortal world by her love for Pei, as well as her unjust death—defends him.

For an author like Zhou Chaojun, this was sixteenth-century wish fulfillment, perhaps, a re-imagining of a world where a ruler could be laid low by a ghost who had possessed no power in life, where righteous scholars could effect change, and where beautiful women came back from the dead for the love of the clever.

But who could blame him? To watch society crumble, year-by-year, is a hard fact to face head on. Easier to do what Tang Xianzu, Zhou Chaojun, and many others did: weave historical reality into their own fantasy worlds, where the usual rules did not quite apply. Love could overcome death, the dead could be returned to the world of the living. Ghosts offered the possibility of retribution, and ineffective leaders received their divine comeuppance.

Zhou’s convoluted, poorly organized, and fantastical script would grow dusty, but his basic plot and characters would return to life, again and again, over Chinese history. Unlike Tang Xianzu, whose scripts are some of the few sacred cows in Chinese dramatic tradition, generations of writers would tinker with Zhou’s story, changing the particulars, trimming plots, changing the dialect. There is something powerful about a righteous phantasm. And so Red Plum took hold in the Chinese dramatic tradition, where ghosts can launch revolutions, and haunt the powerful.

1381

During the early decades of the Ming dynasty, which were just as chaotic as its final decades, a man named Qu You, his dreams of a brilliant official career in ruins, published his New Tales Told by Lamplight, a collection of stories that reinvigorated the old “tales of the strange,” and provided source material for generations of writers, in and out of China.

“The Woman in Green” was just one tale of many. A man named Zhao Yuan one day meets a beautiful girl of fifteen or sixteen, an uncommon beauty unadorned by makeup or jewelry. Working up his courage, he asks where she lives, and she laughingly replies that they are in fact neighbors—he simply hasn’t noticed. A flirtation develops into a full-fledged romance, and after a month he asks for her name. Was it really necessary, she asks, to know her name or learn about her family origins—wasn’t having a beautiful woman enough? After Zhao presses her further, she says only “I often wear green, so you may call me ‘the woman in green.’” Zhao, not wanting to look a gift horse in the mouth, decides not to inquire further, but thinks she must be a servant girl escaped from a noble household.

Another night, Zhao, a bit drunk, teases her with lines from The Book of Songs about a melancholy woman pining for her husband—a man who wears green—who has abandoned her for a concubine. The woman in green takes offense, and disappears for a few days. When she returns, she rebukes her lover for his unkind words, but agrees to tell her fantastic tale.

She was no ordinary servant girl, she explains, but a long-dead servant of Jia Sidao, the prime minister of the Southern Song; Zhao Yuan is no ordinary man, but the reincarnation of her lover of a lifetime ago. Upon discovering that ancient affair, Jia Sidao had ordered them to commit suicide at West Lake.

Was it not fate to meet again like this?

Qu You’s portrayal of the ruler Jia Sidao is as cruel as any that follow. He is abusive to retainers, servants, and concubines, and ignores the suffering of the people. Angry students besiege him with satirical poetry, which enrages him, and he banishes those who challenge his authority.

The callous prime minister is not the star of the story, however. He matters less than the woman in green, who now, having told her story and lived in marital bliss for several years, dies a second death. She shuts her eyes, declaring that the three years she spent with her soul mate’s reincarnation satisfied her mortal desires. After bearing her coffin to its final resting place, Zhao finds it curiously light. Opening it up, he discovers only clothing, a hairpin, and other jewelry inside.

Clothing, a hairpin, and other jewelry. An appropriate end, or beginning, for a ghost that will live many, many more lives. To put on the same clothes again and again, always the same and yet different. Qu You provided an empty vessel, to pour from, or to, the fantasies and fears of generation after generation of writers. More powerful in death than in life, she is malleable and ever changing—but she began simply, nameless, the woman in green. Defying death and tyranny for the man she loved.

Is it not fate to meet again like this?