The Lady Vanishes

In the year 1900, the eerily disembodied shoulders, neck, and head of a pretty young woman appear in a department store window. There she is on a bustling city street in Chicago, a live model in a window display, unembarrassed by her missing half or the staring eyes of the pedestrians before her. Whether it is her absent torso and limbs or the fetching hat on her dark curls, she draws quite a crowd. Then, slowly, unaccountably, she vanishes into the floor. The crowd holds its breath. When she rises back up into view, she is wearing a new hat, but she is also covered in theory. Just dripping with it.

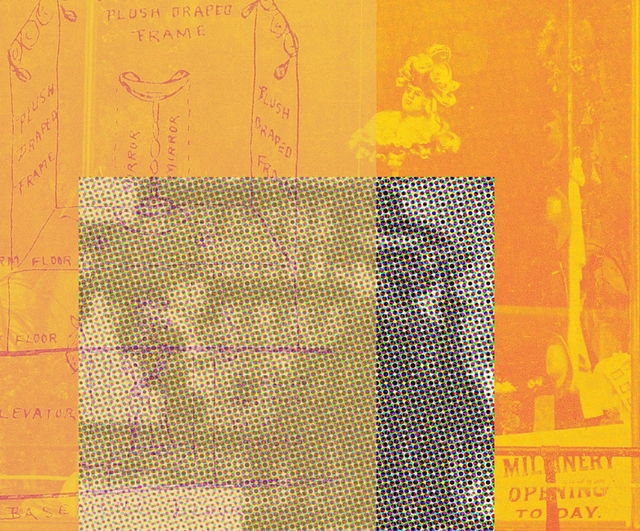

“The Vanishing Lady,” L. Frank Baum, The Show Window. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

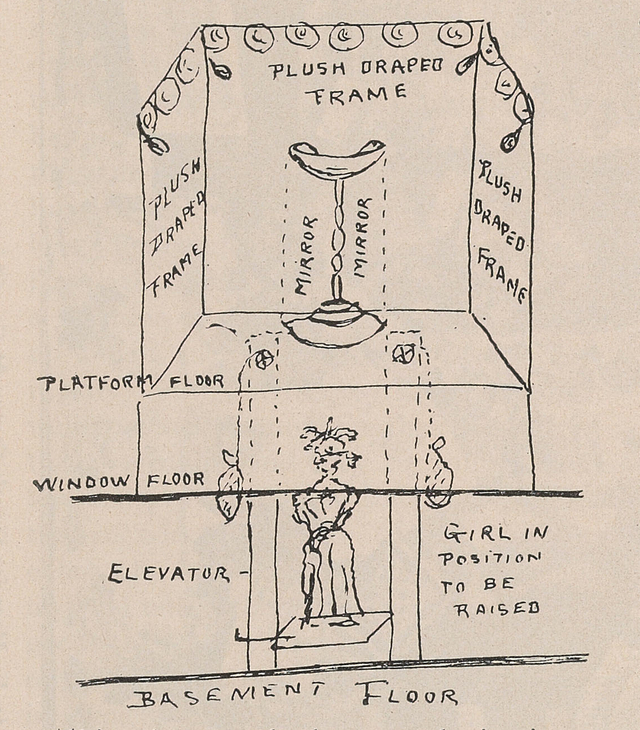

If you are standing in that crowd, perhaps you too feel a thrill as you gaze unabashedly at this strange woman, violating turn-of-the-century decorum. Perhaps you too scrutinize the velvety darkness where her lower half should be. Perhaps you catch the eye of a fellow watcher, sharing a moment of complicity with him. When he surges through the crowd and enters the department store, perhaps you too are tempted to cross the threshold and see what other wonders are displayed inside this new temple of commerce. But resist the urge to follow him. That fellow is almost certainly a “window gazer,” a decoy shopper hired by the department store to lure you from the sidewalk into the store.

“The Window Gazer at Work,” L. Frank Baum, The Show Window. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

And try not to be beguiled by the woman who keeps appearing and disappearing before you every ten minutes. This particular window has already ensnared too many viewers in the century since her appearance—viewers disoriented within the glass shadowbox of moving and heavily-laden symbols.

As the story goes, “The Vanishing Lady” show window was a provocative new millinery display concocted by L. Frank Baum when he was a pioneering window dresser and the founder of a trade journal for the new profession called The Show Window, just before he wrote the book that would make him famous, The Wizard of Oz. Baum’s “vanishing lady” combined two innovations—a live model and a motorized stand—to entice passers-by in the modern city. As a spectacle, the window was a roaring success: so many people thronged to see the vanishing lady that the store was compelled to install an iron bar to keep the glass from cracking. As an advertisement, however, the window’s success is vexingly unknown: the whole point of the display was to sell hats, and sales data has not been preserved.

Nor has the name of the woman behind the glass.

By still another measure, its success continues. Baum’s display has become the most famous show window of its time, enthralling viewers to this day with its usefulness (often in combination with The Wizard of Oz) for the critical theory of gender, spectatorship, and consumer culture. The truncated woman is, most obviously, a symbol of the fate of women in the hands of a patriarchal culture, which puts them on a pedestal at a terrible cost. Or she is the relay in a smooth process that transformed the Victorian woman from a private homebody staring at herself in a mirror, to a public, consuming creature, searching for herself on the cinema screen. The vanishing lady also symbolizes the return of the repressed; she is an “agent provocateur” who subverts the ease with which “the casual shopper [could] lose herself in fantastic identifications with the female image on display … not least because that image keeps evading her.” Instead of seeing an idealized, hyper-fashionable version of herself in Baum’s Chicago show window, the casual shopper sees “a critical presence” who points to all the disfigured and absent bodies produced by modernity.

What all this theory does is ventriloquize the mute woman in the window, to make her indict Baum for the disavowed violence that his glittery spectacles concealed.

Except that the window display in question was not by L. Frank Baum; it did not appear in Chicago; and it did not appear in 1900. Though Baum included the above photo without credit in his 1900 book, The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors, it was not his image or his display. The photo originally appeared in Baum’s trade journal in 1898, accompanying an article by the window’s designer, Chas. W. Morton, who invented the display for the Weinstock, Lubin & Co. department store in Sacramento, California, where he was the head window trimmer. It turns out that the “Vanishing Lady” show window speaks far less about some strange wizard behind the scenes, rubbing his hands together in glee as he designs the next way to oppress the masses, than it does about modern consumption as an anxious, experimental project.

Morton had already made a name for himself as an innovator in window trimming. When Weinstock’s opened their new store at K Street and Fourth Street in 1891, he designed a grand window scene, in which the floor would open to reveal a slowly rising and unfolding rose. Out of the rose would step a little girl, who would flit about the window with a fairy wand, trying on hats and other merchandise, before returning to her flower to be enclosed and lowered back into the floor. Three times a day for a week she repeated her performance, and the crowds were as enthusiastic as they would later be for the “vanishing lady” display in 1898. When Morton won the diamond medal for best display at the national convention of window trimmers the next year, perhaps it was the “vanishing lady” who elevated him above his East-coast peers. Morton’s avant-garde windows were a contrast to the “new” store within, where customers still sat on stools at long wooden counters to wait while salespeople brought them merchandise for inspection. The evolution of consumer culture was far from even.

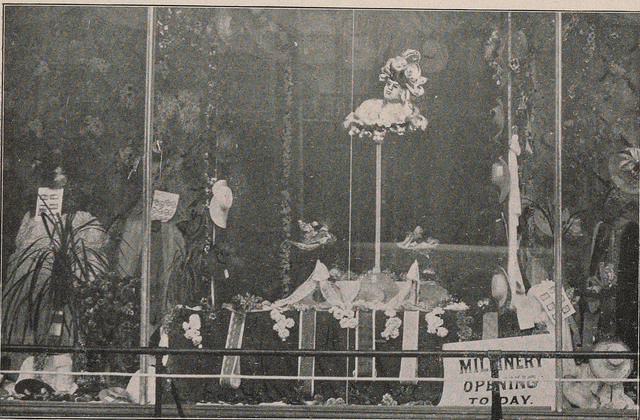

Just as the show window gains history when the frame is enlarged from Baum’s book to Morton’s article in Baum’s journal, so do you attain a new vantage by noticing the literal frame around the Vanishing Lady’s window. Step back across the street, then, and notice what surrounds the enigmatically bobbing woman.

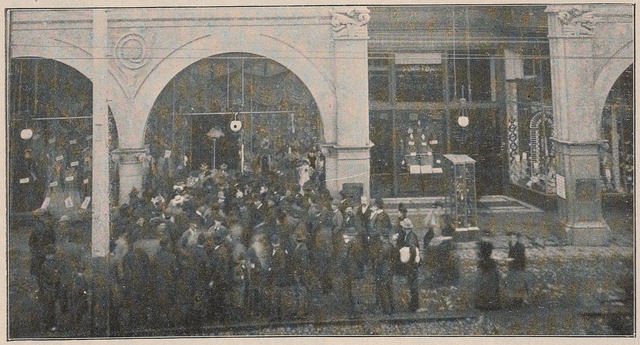

“The Crowd Before Weinstock, Lubin & Co.’s Sacramento Store Watching ‘The Vanishing Lady’” Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

You see a stately white building whose main feature is the wall of show windows running along the sidewalk. Underneath the arches and hanging gas lamps, the windows are set back from the sidewalk by ten-foot-wide covered arcades and accented by freestanding glass display cases. The crowd in front of the window is, indeed, large enough to cause a passer-by to wonder what they’re staring at. But look at the three women on the edge of the crowd, smudged by their own motion. Not for them a “fantastic identification with the female image on display” as they hurry along the periphery. No, the ones who are stilled on the sidewalk in enthrallment before the vanishing lady are all men.

Mr. Morton was most likely abashed at this outcome. The cardinal rule of window dressing, one that The Show Window hammered into its readers each month, was that art should forever be subordinated to sales. “If you can’t make a pretty picture and sell goods at the same time, let the picture go, but make a display that will sell the goods … [A] ‘picture window,’ in which the value or utility of the goods is sacrificed to make the picture, is not art, but foolishness.” It was the beginning of a new commercial discourse, and show windows had to compete with newspaper advertisements and billboards to capture the notice of shoppers. The principles of design then unfolding were about the science of attention as much as the art of display.

Done correctly, a show window would make the needs of a potential customer commensurate with the store’s own desires. The Show Window offered a kind of rational fantasy of the show window’s perfect viewer, a woman named Mrs. Smith, who begins the day by making a list of needed items. “As any well-regulated woman will do she looks carefully through the advertising pages of the daily paper, and notes those items that apply to her list.” With several destinations in mind,

she starts out with a light heart and one of the first things that attracts her is Jenkins’s big show window full of dress goods. Being interested in that line she glances at the window, and suddenly espies just the pattern she had in mind to buy. It is beautifully displayed, in broad daylight. The folds hang very prettily. Why go into a stuffy store and search for anything else when this so nicely fits the bill? Mrs. Smith goes into Jenkins’s establishment and buys her dress.

The same fate befalls the other items on her list. “When seated in the car, homeward bound, she recalls the fact that outside of the thread and pins (which were real bargains, you know) she had not bought a single article at the places she had intended.” It is the balanced outcome: the customer’s trajectory has only ever so slightly swerved away from her map and toward the magnet of the show window, but both store and customer have satisfied each other.

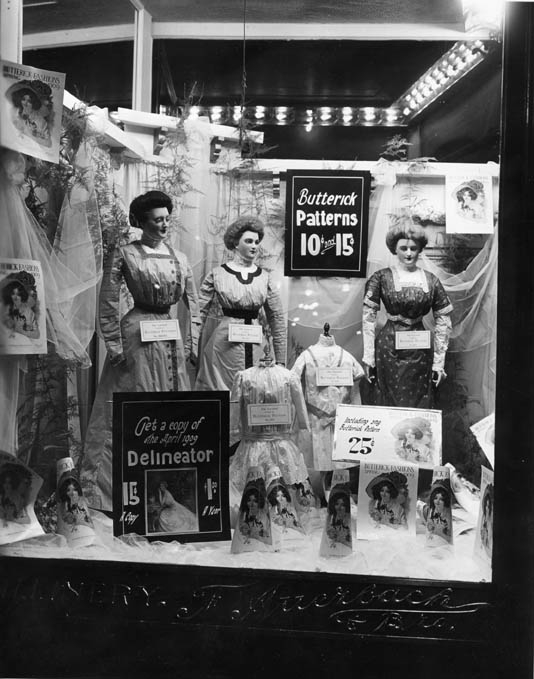

And the audience for window displays was always and forever women. The window dresser’s own formulation of his mission was absolute: the consumer was female, and the window was not only for her—it was her. Mannequins were exclusively female and startlingly lifelike, even then.

Auerbach’s department store window display with mannequins, Salt Lake City, UT, 1909. Thread For Thought

As one window dresser put it, a woman should think to herself, “There is an idea that I could have worked out in my home” or “That dress is just the right combination of materials and colors.”

Yet any photographer’s casual glance at a city street in the early twentieth century would capture the fact that both men and women stopped to look inside the lighted boxes of desire …

Herald Square, New York, NY, between 1900 and 1915. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Window shoppers at Marshall Field, Chicago, IL, 1910. Historiful

… and sometimes just as casually capture the fact that the crowd was composed entirely of men.

Rosenberg Department Store, Taylor, TX, early 1900s City of Taylor, TX

Window Display of ‘Digestit,’ a stomach relief patent medicine, at Brown’s Drug Store, location unknown, 1915 old-picture.com

Even window gazers, the decoy viewers whom Baum recommended that his readers hire in the very first article of the very first issue of The Show Window, were almost exclusively men, as were the window dressers themselves. Women looked and were looked at, but men directed the gaze. But they weren’t terrifically good at it yet.

Just as the photographic evidence suggests that show windows were received in a different way than they were intended, so does The Show Window reveal that its trimmers and dressers couldn’t always theorize what they were doing with the gaze they so fervently sought to capture. Attention turns out to be a dangerous, volatile thing, and the trade journal is a surprisingly dense and poetic record of how male window trimmers understood it in the customers they sought to control, and in themselves when they ventured out onto the streets and were arrested by their own artistry.

Our enigmatic lady is still rising and falling in her window, snagging our own attention. How might we access what the men clustered in front of her were thinking as they stared?

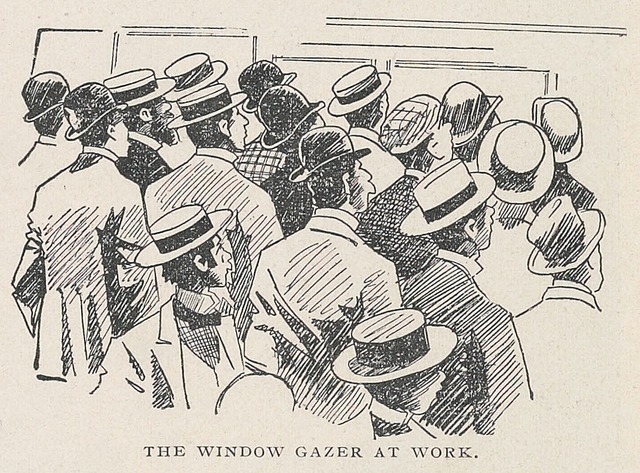

Once again, the answer comes from widening the frame, this time backward into history, to what the crowd might have been remembering. The “Vanishing Lady” show window recapitulated one of the most marvelous illusions from the golden age of stage magic in the mid-1880s, by the French magician Bautier de Kolta. As rival magician Alexander Herrmann wrote, “Its very success was its ruin, so transcendent was it in mystification,” because each illusionist soon devised his own method of staging the trick, and it became a compulsory item on every magician’s program.

De Kolta would walk out onto the stage with an attractive young woman. First he would shake out a piece of newspaper and place it on the stage, so as to later prove that the floorboards had been undisturbed. Upon the newspaper, he would place a chair, and then he would invite the young woman to sit. In Paris, he gave her a mysterious elixir. In London, she prettily folded her hands over her lace handkerchief. He would then cover her with a giant black silk cloth, long enough to obscure her body but transparent enough to keep her visible. He would take a few moments to arrange it around the folds of her dress and tie it behind her head. And then, with a flick of the wrist, he would whisk the silk off. A lace handkerchief would be all that remained on the empty chair. Even the silk in his hands would be gone. To riotous applause, de Kolta would walk to the side of the stage and escort the young woman back out before the footlights.

Ten years later (and two years before Morton’s window display), the former magician and father of modern cinema, Georges Méliès, restaged de Kolta’s illusion as a cinematic special effect in Escamotage d’une dame chez Robert Houdin. In his fantasy, the woman’s disappearance is total, and the magician frantically tries to conjure her back into the chair, at first producing a skeleton, before reappearing the lady herself, fan still demurely in hand.

Georges Méliès, The Vanishing Lady (1896)

There, did you catch the trick of it? If the woman in the show window reminded the audience of her predecessors on stage and in film, they might have been jolted to realize the similarity was not just in the image of the wordless, flickering woman, but also in their own response. Just as at a magic show, the men in front of the window would have leaned in to see how the trick was worked. This was a reaction long cultivated by American popular entertainment from P.T. Barnum onward. It has gathered a cumbersome list of names over the years, that particular gesture of bending toward the ruse, from the “operational aesthetic” to “looking askance.” Put another way, the men on the sidewalk were doing exactly the same thing as the men writing in The Show Window: trying to figure out the principles behind the deception. How was it done?

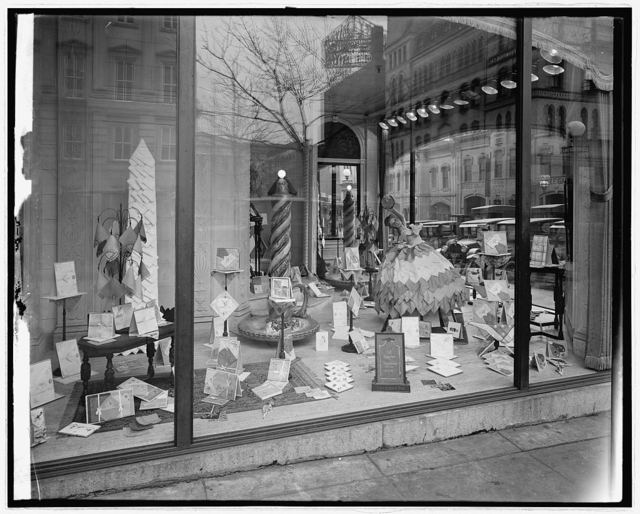

The window dressers’ answer to this question was surprisingly mechanical. They did not try to work on an unconscious level of psychology. The Show Window understood the act of selling as simply the act of getting the consumer’s attention. The typical window illustrated in the journal contained an eye-catching scene that just happened to involve a line of products in an ancillary manner—for instance, a perfect replica of the Brooklyn Bridge built from spools of thread, or a floor-length ball gown made from crisply-folded handkerchiefs.

Department store window, handkerchiefs, location unknown, between 1910 and 1926 Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

“We must startle them,” declared The Show Window, “surprise them, interest them, in order to cajole them into spending their money in our individual establishment instead of our neighbor’s.” The art of persuasion seems to have been a two-step process, in which a pedestrian was first captured by an arresting image and then made to notice a valuable product.

But it was this “noticing” that was itself in doubt at the turn of the century. The new discipline of experimental psychology was taking deception seriously, leaning way, way in to spot the fraud as it was underway, scrutinizing it under laboratory conditions in order to learn the rules of consciousness. Four scholars in particular—Joseph Jastrow, one of the founders of the American Psychological Association, Max Dessoir, Norman Triplett, and Alfred Binet—brought stage magicians into their laboratories to film their prestidigitations, and what they discovered is that the more the mind knows itself, the longer the list of ways it can be deceived. Magicians used the very principles of empiricism to misdirect the audience’s gaze. The psychologists of deception theorized that this susceptibility was inevitable and insurmountable. Triplett wryly noted that, “fixed mental habits, evolved for useful purposes, to avoid being surprised and deceived, are the very agents employed by the conjurer to effect this end.”

But if attention could be so fickle, what was the link between getting someone’s attention and getting a sale?

The Show Window had no ready-made answer to this fundamental question, and each monthly issue further refined their hypotheses about the process. At the turn of the century, the link appeared to be the inherent quality of the goods in their new profusion and variety. Under the right conditions, simply the display of the merchandise was enough to move it. Windows needed to be flashy because of competition, but the fundamental premise behind such advertising was simple: clearing away other visual distractions was sufficient for the goods to rivet the minds of consumers.

So in this scheme, goods had agency—not people. Advertising was not a question of coercion or persuasion because there was no resistance to break down. Advertising was purely a matter of awareness and attention. It was as if there was a direct passageway between one’s eyes and one’s desire or willpower, and appealing to the former seized the latter.

And for many of the viewers before the window, this theory proved all too true. A shocking number of middle-class women testified to being so overwhelmed by show windows and the sensory stimuli inside the department stores that, quite despite themselves, they stole from the tables heaped high with goods. “The things were there,” one woman confessed, and she could “no more control the action of her hands than she could fly.” The phenomenon of the respectable shoplifter exploded in the decades before the turn of the century and challenged the orthodoxies about class and gender roles that department stores purportedly reinforced.

For other viewers, though, the transgression urged upon them by the windows was less overt. The “peripatetic philosophers,” as the Show Window termed the city’s male flâneurs, quickly discovered that an alluring display might sabotage what Walter Benjamin called “illustrative seeing,” the detached, amused observation of the urban scenery. A millinery window like the one that featured the “Vanishing Lady” could serve as “fresh matter on which to nourish his musings.” The hat display is

really a delightful little affair, although men are not supposed to be interested in such matters. However, they will cast stealthy glances in at the windows now and then, and the funny, fluffy little bits one sees there are not so unattractive, after all. There are white mousseline arrangements—they must be baby hoods. These are generally nestling at the stalks of painted wooden standards upholding those terrific collections of mineral, animal and vegetable matter called ‘bonnets.’ These are dreadful, but somehow they fascinate one, and then they allure one to gaze on.

But too often in the Show Window, this attention to feminized objects unsettles the viewer. Another philosopher was disturbed to find that one window “kept me a prisoner for half an hour a while ago, and the queerest thing about it is the fact that it is the window of a millinery establishment, and is filled with all the latest ribbons and feathers and flowers.” The window hijacked his thoughts and sent him back into his own past: “I found myself thinking about those Paris hats and comparing them with the old checkered sunbonnet my mother used to wear.”

The problem is that the objects in the window are not inert. The most telling example of male bewitchment is an astonishing story called “The Merciful Wax Lady,” in which a man criticizes the seductive arts and shameless, aloof demeanor of window mannequins, for whom “the most ardent glance cannot provoke a blush on their cheeks.” He then wonders if his critique is overly harsh, so he shows his writing to a wax lady, who confirms that she does, indeed, have the power to “haunt him to his dying day, and forever keep him from a human woman’s arms.” In a reversal of the male gaze that imprisons its female object, the mannequin’s gaze threatens to dissolve the writer’s sense of self. “She turned and gazed full into my eyes. For a minute I was lost. The world fell from me and I could not think or hear, or feel aught but the glory of her eyes. Then she turned away her head disdainfully. ‘Go, poor fool!’ she said. ‘If I but willed it, you would never more leave my side. But I am merciful—go!’”

Georges Méliès, L’artiste et le mannequin (1900)

The direct passageway between the eye and the mind that the Show Window theorized grows labyrinthine. No longer do objects make claims for the mind calmly to weigh and judge. The rational fantasy of a window that aids a well-regulated shopper falters, because the goods in the window are not self-evident. They do not signify only their own inherent worth. Suddenly they move and talk, and when they no longer stay still, the question of who is influencing whom grows slippery. Instead of a window display so interesting that it engrosses the female pedestrian and causes her to consider a commodity, we see show windows that ensnare the male pedestrian and cause him to reconsider his very self. If this process happens despite the intentions of the male pedestrian, who grants the objects in the display their power? Who is in control of the narratives, associations, and images prompted by the spectacles in the window?

In one Show Window poem, a wife complains at the overly affectionate attention her window trimmer husband lavishes on his mannequin. In a short story, a doll resists the trimmer’s efforts to pose her in the window—a struggle in which the trimmer is described as a “brute” who violates his “victim” first by wrenching her into place and then by forcing her to hold a sign advertising herself for sale. A feature article trumpets the cleverness of a black display mannequin that “will well repay, as an advertisement, any merchant who consents to purchase a little nigger, even though slavery is a thing of the past.” The journal could not be more literal about its own anxieties.

Again and again in the pages of the Show Window, stories and poems inject personality into the lifeless objects inside the displays, to explain their disproportionate ability to fascinate. This is exactly the opposite move detected by critical theory, which tends to see violence or deadening in the window displays, or the urge to deny the commodity status of the goods by aestheticizing them. But in fact the window trimmers at the turn of the century were haunted by the power they had unleashed. Did it have a limit?

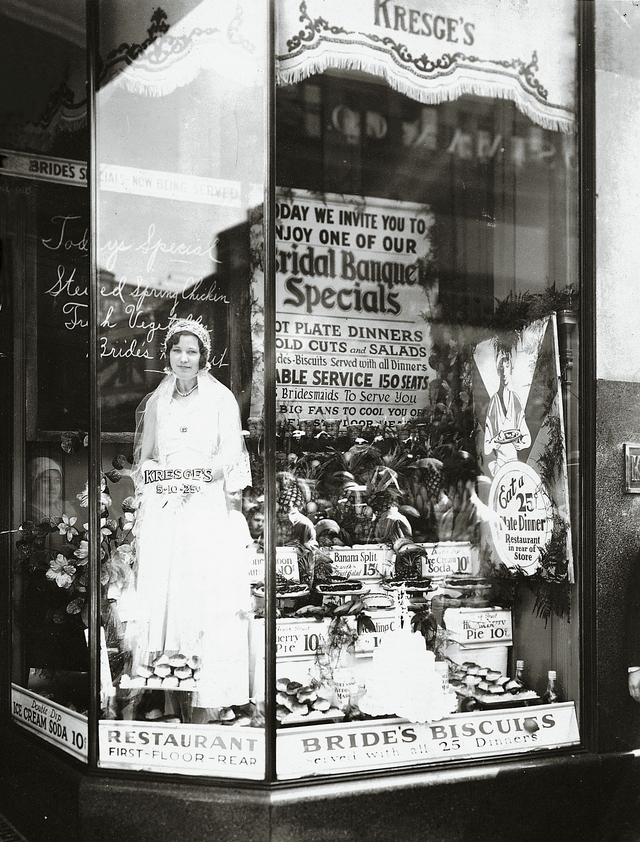

Live female models parade around the windows in circles, holding cards with the prices of their dresses on them. A hypnotist puts his wife to sleep in a window and leaves her there for the crowds to stare. “Even men did not disdain to gaze curiously upon the hypnotized form,” L. Frank Baum marvels. A Native American man dresses his “squaw” in furs and leaves her to sleep in a trading post window.

Live model in Kresge’s 5-10-25¢ store on Market Street in downtown Philadelphia, late 1920s or early 1930s Reminisce.com

How far does fungibility extend? Can personhood somehow be accidentally traded away or bestowed through seemingly routine commerce in material goods? The Show Window’s anxiety spilled over onto itself. Repeatedly, in stories and poems, it is the window trimmers themselves who are “bought” when their displays so seduce their customers, male and female, that they storm inside and imperiously propose marriage. One trimmer is propositioned with “a brand new dime.”

If the Show Window’s vantage on the turn of the century is representative, then it allows us to peer at something often obscured in the onrushing modernity of the age: the fear that accompanied emergent display technologies and design trends. The gaze that window trimmers coerced and conducted could go awry, could turn around and engulf them, like a stage illusion that vanishes the magician. Perhaps this is why so many windows depicted the act of consumption.

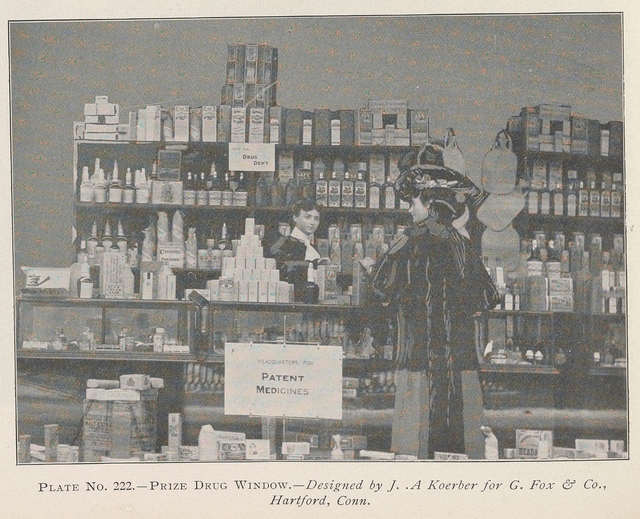

“Prize drug window,” L. Frank Baum, The Show Window Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

All windows acted as synecdoches for the store inside, a kind of visual index to the class status for sale with the currency of taste. But many of those windows metonymized consumer culture in a more forthright way by depicting it explicitly and literally, seeking to pin in place the actors in their roles. It is this quality, the self-reflexivity of a hyperfictional form, that L. Frank Baum’s journal, the Show Window, reveals to us even as it depicts the straying gaze. What the vanishing lady demonstrates is not the unswerving male dominance that we find in theory, but the jolt and lurch of male anxiety as it moves along the uneven tracks of modernity in the consuming age.

The lady is reappearing within her window. Lean closer. Do you see how it’s done?