Tuned to the Senses: An Archaeoacoustic Perspective on Ancient Chavín

The author, making acoustic measurements of the stone-and-mortar surface of “Building A” in the ancient ceremonial complex at Chavín de Huántar, Perú. José Luis Cruzado Coronel

Sound and Archaeology

Buttressed into the Peruvian Andes, the ancient mortared-stone complex at Chavín de Huántar resonates with sound and story. Visitors to this 3,000-year-old ceremonial center frequently don’t notice the isolating silence and surprising resonances of its labyrinthine interior architecture. Site acoustics don’t stand out in the conspicuous manner of reverberant cathedrals, and architectural sound isn’t something most people pay attention to anyway, since we’re used to tuning out background noise.

Sound, both heard and felt, dynamically connects us to the physical world through sensory and cognitive interaction. We’re not always thinking about what we hear or feel, yet sound is an environmental channel for information about the world around us. Sonic experience is most obviously rooted in listening, but it’s not only about the ears, and individual background and attention shape many aspects of our perception of sound.

Over the past six years, I’ve measured Chavín’s acoustics and conducted human auditory perceptual experiments aimed at understanding the role sound played at ancient Chavín. “Integrative archaeoacoustics” brings together tools and techniques from acoustics, audio engineering, perceptual psychology, anthropology, computer science, and other fields in a novel approach to exploring ephemeral aspects of past life. In my work, scientific method guides theory and measurement, but I have to consider the subjective possibilities that physical dynamics—such as acoustics—create for human experience. If I were to summarize my expertise, I might say “cultural acoustics.” I focus on understanding how sound influences people, what people do with sound, and what this means for humans as individuals and social beings.

Archaeologists toe a wavering line: as professionals, we strive to present a transparent account of our explorations and discoveries, but at the same time, we’re compelled to create narratives that explain our activities and motivations. We report on findings, produce interpretations. Sometimes we find ways to communicate the ambiguities of this terrain, but often our interpretations are mistaken for direct knowledge of the ancient past. However archaeological findings might be presented and understood, material culture is the entryway. With its well-preserved architecture and intact, sound-producing/musical instruments, the ancient pilgrimage center at Chavín provides the multifaceted material evidence needed for an archaeoacoustic case study.

Ancient Instruments Sound Again

What does it mean to excavate a musical instrument from its resting place of three millennia?

Archaeologist John Rick and his teams had the great fortune—and brilliant insight—to uncover a cache of twenty decorated Strombus galeatus conch shell ‘trumpets’ in 2001 at Chavín, a Peruvian national monument and UNESCO World Heritage site that welcomes visitors. These intact pututus—as musical horns of marine snail shell form are called there now—were the first ceremonially associated sound-producing instruments to be excavated at Chavín, and the only ones known from its extensive lithic art.

Peruvian master musician and instrument builder Tito La Rosa performs with one of the Chavín pututus to demonstrate the musical potential of the ancient shell horns during a research session at the Museo Nacional Chavín in 2008. José Luis Cruzado Coronel

The stunning preservation of these pututus meant that they could be handled carefully and even played. Rick first called on his experience as an avocational musician to document the readily blown tones of the instruments, using the guitar tuner he had on hand. Later, he sought the expertise of sound specialists: Peruvian musicologists and musicians, as well as California acoustician David Lubman, brought their present-day perspectives to assess the overall sonic potential of the shell horns. One of Rick’s then-undergraduate advisees, Parker VanValkenburgh, took on a morphological and iconographical study of the instruments as his honors thesis project, an ambitious and productive study that illuminated plausible regional interconnections. Using a range of approaches, Rick’s team began working to document the pututus and understand their relationship with Chavín.

Chavín iconography depicts marine shell objects and instruments, such as the pututu held by the first figure in this cornice fragment discovered on site by John Rick and teams. José Luis Cruzado and Miriam Kolar

Implications of the Chavín Strombus horn discovery traverse the historical timeline. We can date these pututus with excavation stratigraphy in terms of deposition era, and their markings from hand and lip wear indicate long-term use. What they represent in terms of site knowledge is important: instruments excavated from ceremonial architecture—and prominently depicted in its graphic record—can be contextually associated with site ritual. These ancient shell horns are intact and playable, so they might be performed well into the future. This is especially important from a methodological point-of-view, because developing technologies can reveal new forms of evidence as tools change, a possibility Rick is constantly considering.

Given Rick’s investigatory savvy, it’s no surprise that a few years after unearthing the Chavín pututus, he found a way to make them sound again, this time for the purpose of exploring and documenting their range of acoustic potential. Enter researchers from Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), including then-Princeton computer science/music professor and shell instrument player Perry Cook. Our starting point was the pututus, but project organizer and CCRMA founder John Chowning also sought to incorporate his colleagues’ expertise in spatial acoustics and computational acoustic modeling, areas dear to faculty math-and-engineering wizards, Jonathan Abel and Julius Smith.

Stanford consulting professor Dr. Jonathan S. Abel led the archaeoacoustics team’s development of the “bouquet” microphone array prototype and calibration system used to document Chavín gallery acoustics. Miriam Kolar

Since our 2007 formation, my team has focused on testable scientific aspects of Chavín’s sonic story. Back at Stanford, we developed plans for on-site research that would pioneer tools and methods to explore, archive, and digitally preserve site and instrument acoustics. Rick continually offered information and insights about the setting, but, as we sound specialists learned during our first visit to Chavín, without first-hand site experience it had been impossible to adequately understand the demands of the place and the implications of its archaeology. We refocused, and I began my multi-year Andean immersion in archaeoacoustics fieldwork. What were the practical challenges of Chavín as a research venue where we would apply custom tech in fieldwork? How would acoustics findings meld with anthropological considerations to bolster the archaeological story?

Chavín Archaeoacoustics: An Exemplary Case Study

In the 1970’s, Peruvian archaeologist Luis Lumbreras and teams discovered a terraced canal running beneath Chavín’s Circular Plaza staircase that created a tremendous sound effect when water was poured through. This was the first documented archaeological consideration of sound at Chavín, almost thirty years before the pututu cache was uncovered. Conservation limits such physical testing, so questions of the site’s ancient sound environment were put to rest for decades with the 1976 publication of an article that estimated hydraulic sound effects related to the monument’s extensive subterranean canal system and interior architecture. Now, armed with non-invasive research tools, my team’s on-site archaeoacoustics fieldwork has introduced new technologies to probe the elemental and potentially subversive sonic environment of this proposed oracular center.

Chavín’s monumental architecture has been partially covered and destroyed by landslides and human activity since its development period estimated between 1200 and 500 B.C. Its stone-and-mortar architecture includes tall buildings, multi-level terraces, and sunken plazas spanning kilometers, as well as subterranean canals that interlace the site and connect its two surrounding rivers. José Luis Cruzado Coronel

An enigmatic stone monument located in the north-central sierra of present-day Peru, the expansive complex at Chavín is known as a ceremonial center, a “temple”, an “oracle site”, or a spiritual locus. Archaeological investigations in this narrow Andean plain—the site of multiple landslides and the convergence of two powerful rivers at 3180 meters above sea level—have unearthed extensive findings. A diverted river, kilometers of subterranean canals, vista-occluding ceremonial buildings, and associated domestic and workshop areas all offer evidence of transformative landscape modification performed by ancient humans. Monumental construction seems to have been continuous for nearly a millennium, recently dated by Silvia Kembel and Herbert Haas from around 1200 to 500 B.C.

As Daniel Contreras has eloquently argued, the complex at Chavín demonstrates human domination and ongoing management of a risky natural environment, a political accomplishment that seems particularly well-aligned with the site’s renown as a cult center pivotal to, or emblematic of, the growing social hierarchical differentiation that took place during the Andean Formative Period. Social stratification has been identified in evidence from the monument’s surrounding residential and production areas through the work of researchers such as Matthew Sayre and Christian Mesía.

A figure holding an object resembling the so-called “San Pedro” cactus, a psychoactive plant that grows in the region, is carved in relief on one of the facing-stones that line Chavín’s Circular Plaza. José Luis Cruzado and Miriam Kolar

Theories to explain and characterize religious activity at Chavín range from speculation to solid anthropology; among the most recent and widely accepted are Richard Burger’s arguments for a “Chavín Horizon” of dispersed Andean influence around the site and its cult, Luis Lumbreras’ material and economic interpretations of widespread power structures centered at the monument, and Rick’s detailed arguments for “an evolved Shamanism” in the context of “a tradition-based convincing system” built at Chavín.

Evidential bases for these views highlight sensory and experiential clues. Myriad stone and bone tools for the preparation and consumption of psychoactive plants have been excavated from the site and its surroundings. Larger-than-life human, animal, and anthro-zoomorphic sculptural stone heads once lined exterior building walls, projecting the extreme grimaces, upturned eyes, and nasal mucus trails typical of such plant use. Labyrinthine, deeply enclosed interior spaces where light could be excluded or manipulated using polished coal mirrors and shadow projections interlace site buildings. Chavín has been described by many as a theatrical ritual venue: its varied architectural features present contexts for one-to-many address, sound projection, and group gathering areas, as well as intimate spaces that could isolate individuals and perhaps facilitate psychotropic experiences. Sensation took focus at ancient Chavín, and though there are many senses to consider, the sonic dimension is particularly provocative due to its subversive immediacy: it creates effects that are experienced, but not necessarily identified.

Larger-than-life “cabezas clavas” or tenon heads once loomed above Chavín, pegged into the exterior walls of its ceremonial buildings. The human, animal, and hybrid forms may depict ritual or mythological transformations, with features such as upturned eyes, nasal mucus, and extreme grimaces hinting at psychotropic plant use. José Luis Cruzado Coronel

Archaeoacoustics methodology gives us a way to identify such environmental sonic components that contribute to the feeling of place and its communicative possibilities. Beyond first-hand sonic tests—like performing a replica pututu in a Chavín plaza—and the identification of apparent sound effects—such as echoes among building faces and surrounding hillsides—equipment-based acoustic measurements of Chavín’s well-preserved interior spaces can map how sound is transmitted and transformed by the architecture. Understanding how sound morphs as it propagates through space is essential to documenting and estimating the basic features of an ancient sonic environment. The use of gear can change results, and the researcher determines test parameters. Such acoustic measurements can be used to preserve the sonic contours of spaces, yet these encoded data don’t tell us their contexts; they merely give summaries of places at moments. There’s embedded research perspective that needs to be documented, and many angles of access to the embodied clues of past experience.

Acoustic measurements of the Chavín site employ diverse techniques and equipment. Left: Miriam Kolar wears in-ear microphones to make recordings that enable researchers to evaluate how spatially imprinted sound is received by a human listener; center: the fragmented exterior architecture of Chavín buildings hides well-preserved interiors as shown right: a directional loudspeaker and subwoofer allow consistent reproduction of the mathematically generated audio signals used to measure the acoustics of Laberintos Gallery. José Luis Cruzado Coronel

In my archaeoacoustics work, I wield manual instruments such as measuring tapes and laser distance finders, and computational tools such as MATLAB in order to implement mathematical audio digital signal processing (DSP) code. There is no typical day of field work for me at Chavín: one morning, I might crawl through slate-lined canals built three thousand years ago, listening to the silence and the closeness of my breath, looking for places where sound can enter and exit. The next afternoon, I could climb a scree-covered hillside to hear a mix of brass funeral bands, Huayno radio, traffic and construction noise drifting up from the Andean town below, to assess longer-distance sound transmission. Some days I bang my brain against numbers on my computer, tweaking formulae to generate audio test signals, strategic sounds to be played through loudspeakers with the ambient responses digitally recorded via microphones positioned to capture selected spatial dynamics. Other days I hang out on the phone discussing analytical challenges with mentors and colleagues back at Stanford.

Measured acoustic properties of site spaces—and estimated acoustics from evidence-based models—can then be evaluated to understand human perceptual implications. The same principles apply to studying musical instruments or objects that produce sound, but on a smaller physical scale. If both spatial acoustics and instrumental sonics are understood, a comparative analysis can be made to estimate the effects of their interaction—how a space enhances or changes the sound of an instrument—and these characteristics can be further evaluated in terms of known human perceptual correlates. It’s a chain of relational data that depends on good documentation, math, and careful reconstruction techniques to pull together findings across disciplines.

Making acoustic measurements in the Lanzón Gallery: the CCRMA prototype “bouquet” array of Countryman B6 microphones used to record acoustic test signals played from a Meyer MM-4XP loudspeaker in order to evaluate interior architectural acoustics. José Luis Cruzado Coronel

To get at the sensory implications of material traces, we look to psychology. Although the transformative effects of perception may vary individually, extensive systematic experimentation has led to functional understandings of human perception. Knowledge about psychophysics—the interplay of stimuli and sensation—can guide the archaeological appraisal of how sound might have affected people in an ancient context. If characteristics of an ancient spatial sound environment can be estimated from extant architecture, landforms, or other spatial evidence at an archaeological site, auditory implications for ancient occupants can be evaluated.

Take, for example, the so-called “precedence effect”, a well-understood auditory perceptual phenomenon. Real-world environments contain surfaces and objects that divert, absorb, and reflect sound, creating multiple paths for sound to transmit between its generating source and a listener who are separated by space. Based on hearing alone, a person tends to perceive the direction of the source location with the earliest arrival of sound energy—the shortest sound propagation path—even when there are many sequential sound reflections (that can be “louder”) from other directions. Architectural acoustic measurements and computer models can be used to estimate how the precedence effect might be induced in ancient sonic contexts.

Acoustic and perceptual sciences can be applied together to better understand the sensory potential of an ancient sound environment. Where on-site perceptual experimentation with human participants is possible, consensus testing across a group of people can confirm estimated experiential components. Psychoacoustic laboratory experiments may also be designed to evaluate the human auditory implications of site acoustics. Combine this knowledge with other information about the archaeological context, and compelling clues about ancient human experience emerge. Experiential possibility is rooted in material fragments. Hard evidence—Chavín’s carved shell and mortared stone—is a weighty but enigmatic guide to the past.

Acoustic Alignment of Instruments and Architecture

Dr. Perry R. Cook performed the Chavín pututus during acoustic measurements of the instruments made at the Museo Nacional Chavín in 2008. Left: Countryman E6 microphones were positioned inside the Strombus shell horns to record acoustic transmission from the mouthpiece to bell; center: Chavín project director, archaeologist Dr. John Rick and Cook position microphones; right: Cook plays the pututus for measurement, using a systematic sequence of performance techniques. Jyri Huopaniemi and José Luis Cruzado Coronel

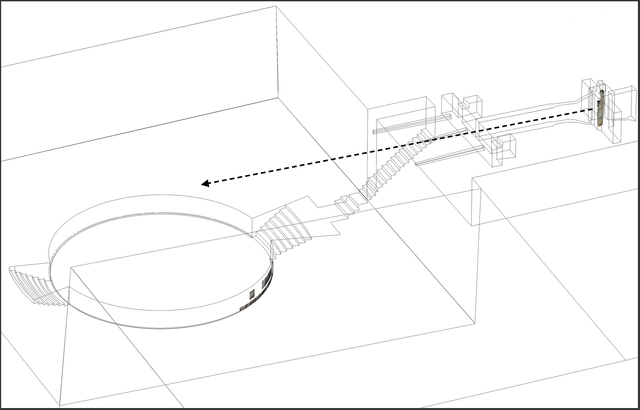

My team’s comprehensive acoustic workup of 19 of the 20 Chavín pututus gives us details of their functional characteristics that can be used to estimate their interactive potential with site architecture. The so-called “sounding tones” of these instruments—the readily played frequencies that a musician might call “pitches”—measure between 272 Hz to 340 Hz (approximately “middle” C#4 to F4 on a standardly tuned piano). In one of the most compelling instrumental and architectural correspondences that we’ve documented to date, these specific sonic frequencies are amplified by 10-20 dB (10 dB is like turning up the volume on your music player to make it seem twice as loud) above all other sound by three architectural ducts in a key Chavín ceremonial location. These horizontal ducts connect the interior gallery of the “Lanzón”, the 4.5 meter-tall engraved granite monolith, with the exterior Circular Plaza. In its physical alignment, the central duct provides a direct line-of-sight—and, as supported by acoustic measurements, a plausibly symbolic and functional “line-of-speech”—between the carved mouth of the imposing fanged figure and the outside world of the plaza.

Sparse reconstruction of Chavín’s Circular Plaza and Lanzón Gallery architecture shows the “line-of-speech” between the interior Lanzón monolith and the exterior plaza, through the central duct that acoustically emphasizes tones of the site-excavated shell instruments. Reconstruction by José Luis Cruzado Coronel, from data by Silvia Kembel, John Rick, and new on-site measurements

The architectural acoustic link between the Lanzón Gallery ducts and the site-excavated sound-producing instruments is a rare gem of archaeological correspondence that’s difficult to dismiss as coincidence. First, Chavín’s architecture is thoroughly channeled with ducts of different shapes and sizes. Therefore, unique structures of a particular size and placement among these ubiquitous forms suggest planned construction: design.

Second, the location of these tuned sound conduits—between the consequential stone monolith and the exclusive plaza setting—would be ritually significant, and it’s riddled with other links to shell horns. In this apparent ceremonial locus, pututus are depicted, as if performed by figures in procession, on stone reliefs lining the north-western wall of the Circular Plaza, just a few meters away from where the Strombus-projecting ducts open onto overhead walls. The plaza floor was crafted with two inlays of fossilized sea snails on its paving stones, spiraled animals that appear like cross-sectioned pututus. A few meters south, a plausible pututu storage location exists: in the Caracolas Gallery where Rick’s team unearthed these instruments, they were deposited as if they had been hung along its walls. This constellation of factors provides strong support for the idea of ancient ceremony enlivened by the sound of these horns. Converging forms of evidence connect pututus to the Circular Plaza, and dynamically connect the plaza with the hidden Lanzón monolith. The building specifically projects the sound of the site-excavated instruments—and excludes other sounds—from the mouth of its “oracle” to listeners outside.

Facing-stones that line Chavín’s Circular Plaza depict figures holding pututus, as if performing them in procession. José Luis Cruzado and Miriam Kolar

Echoes of Ancient Experience

Sound—because it’s experiential—is an ephemeral artifact of spaces and objects that we can use to better understand past life. Some archaeoacoustic research is persuasively manifest for present-day observers: hearing a sequence of replica pututu echoes circling around Chavín’s valley can’t transmit cultural meanings from the past, but through this experience, one better appreciates the dynamics of setting that would have influenced ancient human activity. Performing a replica shell horn inside Chavín’s galleries, I can feel through my body the resonances between instrument and architecture, a physically and emotionally transformative experience that would have been similarly sensed—but interpreted differently—by humans in the past.

Scientific research techniques based on material evidence of the distant past give detail about the less apparent aspects of sound that are fundamental to human experience. Such findings permit reconstructions that can further illuminate elemental characteristics of ancient sound environments. Using a computational acoustic modeling tool based on measured acoustic data and auditory perceptual experiment findings, we can test and auralize the acoustic effects of space by virtually reconstructing site areas that are no longer intact. Measured and modeled sound transmission dynamics across site spaces suggest how people could have used sound to communicate or influence the perspective of others in ancient Chavín. And acoustic measurements have demonstrated that Chavín’s site-excavated pututus are dynamically linked to its imposing Lanzón monolith: instruments and architecture together make a sounding “oracle” mechanism that could project secrets from the restricted depths of the site to its public, dominating exterior.

Archaeoacoustics at Chavín continues, as we engage these and other research approaches to better understand the social implications of sound environments for people in the ancient Andes. Echoes of ancient experience tell us more about our human roots in another time and place, offering fragments of a non-verbal history.