Letter from the Editors: Futures of the Past

How have past generations imagined their collective futures—and how do we? Detail from Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, 1563, Kunsthistorisches Museum (via Wikimedia Commons)

Nabopolassar, like any ancient Mesopotamian king worth his salt, was not a modest man. A self-described “son of a nobody,” he had risen from obscurity to lead a revolt against Assyria and reign over a restored Babylon for twenty years. The king’s conquest of the city of Nineveh even made its way into the oral tradition that would become the Hebrew Bible (“Woe to the city of blood, full of plunder, never without victims”).

But Nabopolassar was interested in building up as well as tearing down. In a clay inscription he deposited in the foundation of a temple, Nabopolassar boasted of his restoration of ancient ruins, “which had weakened and collapsed because of age; whose walls had been taken away because of rain and deluge.” The King, it turns out, had mobilized his peacetime troops to dig into the foundations of the ruined temple and explore the relics of previous ages.

In this buried inscription, Nabopolassar proudly added another title to his royal epithets: “the one who discovers bricks from the past.”

Nabopolassar, it has been argued, was the first archaeologist. But his inscription looks forward as well as backward—not to the past, but to an imagined future. By burying this text in the foundation of his rebuilt temple, Nabopolassar was thinking ahead to the picks and shovels of future generations—to a time when he would be the ancient king, when his new temple walls would crumble and collapse.

In an oblique way, he was thinking about us.

“Futures of the Past” is an issue about how past generations have reckoned their collective futures. But it’s also about how the razor’s edge of the present comes up against the haziness of futurity, and what happens when that hazy future becomes inscribed, remembered, and—eventually—forgotten. We’re interested here not just in retro curiosities or Tomorrowland nostalgia (although there’s some of that), but in the work that the future does in shaping history—as a utopian dream, a set of collective anxieties, or simply as a story that we tell about where we come from and where we hope to end up.

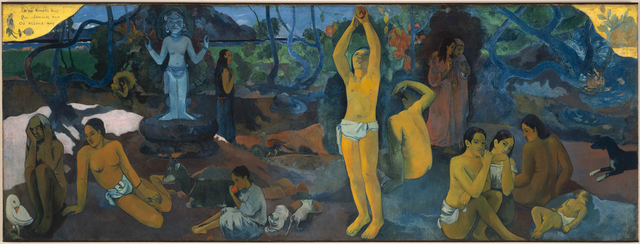

Paul Gauguin, Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1897 (via Wikimedia Commons)

Several pieces in this issue suggest that we should study the futures of the past not simply because they’re quaint or charming, but because they show us that even our most confident predictions can go wrong.

That’s the inspiration behind the first “chapter,” or monthly grouping of articles, that kicks off this issue. We call it “Bad Predictions,” and it includes prophecies that didn’t quite hit their mark, as well as fears of dystopian futures that were, unhappily for us, all too real.

The chapter begins with Grant Wythoff’s research into the origins of radio. Wythoff argues that wireless telegraphy—and the science fiction dreams it inspired—stirred up prescient fears about the ways that emerging technologies can enable government eavesdropping. From the Golden Age of science fiction we venture backward into classical antiquity, where Sarah Bond and Matthew Neujahr explore how ancient Roman dream interpretation offered an unreliable glimpse into futurity. In her article on the reproductive politics of spaceflight, Lisa Rand shows how Cold War era visions of space-faring women remained mired in misogyny. And while the seventeenth-century predictions about future scientific discoveries described by Anna-Marie Roos are often eerily accurate, we’re still waiting for “Attaining Gigantick Dimensions” and “the Recovery of Youth.” Other articles, like Rebecca Onion’s exploration of nuclear fears among ’80s kids or Marissa Nicosia on fears of “monstrous” futures after the English Civil War, dig deeper into the theme of dystopian futures, while Christopher Dietrich narrates an unexpected swerve toward a collective future of resource scarcity and sectarian violence in Vienna, 1975.

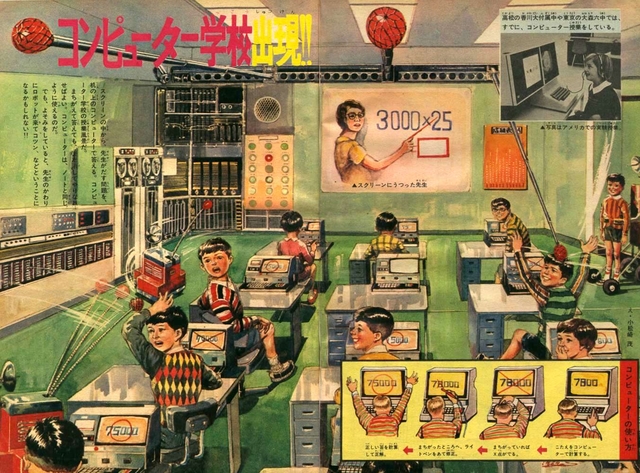

“For the purpose of maintaining order, the future classroom will come equipped with watchful robots that rap students on the head if they lose focus.” Shōnen Sunday, 1969. Dark Roasted Blend

Not all futures are bad, however. Some visions of of the future swiftly recede into pasts bathed in the haze of nostalgia, a theme explored in Chapter Two: “Futures Past.”

In a standout piece of longform journalism, Chris A. Smith journeys to Zambia to uncover a story of musical dreams deferred. Next, Michael P. Williams mines twentieth-century Japanese youth culture and its fascination with dystopias and utopias, from visions of robots in the classroom to a cult-classic 1990s Super Nintendo game. Appendix editors Lydia Pyne and Ben Breen document imagined futures (of Neanderthals and island micronations, respectively) that never quite panned out, while artist Jed McGowan illustrates a bygone age of prophecy. Brooke Palmieri’s unexpectedly racy history of seventeenth-century Quakers reminds us that almost all religious movements have utopian roots. Rounding out the chapter, Laura Martin uncovers the utopian “cadets” that inspired a beloved children’s book, and Aaron Sachs summons the ghost of Lewis Mumford.

Our final chapter, “The Politics of the Future,” reminds us that prediction is a political act. Imagined futures can be powerful tools for social change, but they can also reproduce the injustices of the present—as Erin Pineda explores in a thought-provoking feature article about the 1964 New York World’s Fair and the Brooklyn Civil Rights organization that tried to stop it. Matthew Goldmark asks whether the fictional future of Star Trek repackages colonialism in space, and Rachel Marcy draws on over a dozen interviews with former ballet dancers to reconstruct how dreams of US-Soviet cultural exchange became mired in political saber rattling. The supposed Dead Sea Scroll at the center of Michael Press’s article was either a priceless treasure or a laughable fake depending on your point of view, while the mutants of the 1960s Marvel comics universe were, according to John Wenz, uneasy amalgams of scientific progress and nuclear anxiety. Finally, Kevin Cannon returns with another illustrated map, this time of Yuri Gagarin’s first flight into space.

In the fascinatingly wide-ranging conversation that closes “Futures of the Past,” noted historians D. Graham Burnett and David Gissen ask, “How do you see beyond the horizon line?”

Burnett relates the experiences of one William Scoresby, an early nineteenth-century whaler who reported a fascinating atmospheric phenomenon. Perched high on a crow’s next, scanning the horizon for icebergs, Scoresby realized that “reflected light under the cloudy sky could actually throw up onto the underside of the clouds a nebulous and difficult-to-read, but nevertheless legible, reverse image of the patterns of pack ice.” As Burnett points out, this is a fabulous metaphor. By looking upward, into the limitless expanse of the sky and the nebulous outlines of clouds, it is possible to predict the very solid, and very dangerous, contours of icebergs ahead. By looking up, we learn about what’s lurking below.

And, perhaps, when we look forward into the future, we’re actually looking backward, at where we began. The brilliant final poem of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, published at the height of World War II, was about precisely this:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Through the unknown, unremembered gate

When the last of earth left to discover

Is that which was the beginning;

At the source of the longest river

The voice of the hidden waterfall

And the children in the apple-tree

Not known, because not looked for

But heard, half-heard, in the stillness

Between two waves of the sea.

But if that all sounds a bit too heady, at least we can take solace in the words of George Carlin.

“The future,” he reminded us, “will soon be a thing of the past.”