Present Tense, Future Perfect: Protest and Progress at the 1964 World’s Fair

If every Negro in New York

cruised over the Fair

in his fan-jet plane

and ran out of fuel

the World

would really learn something about the affluent

society.

The stink of the fire hydrant drifts up

and rust

flows down the streets.

The Shakespeare Gardens in

Central Park

glisten with blood, waxen

like apple

blossoms and apples simultaneously. We are happy

here

facing the multiscreens of the IBM Pavilion.

We pay a lot for our entertainment. All right,

roll over.

—Frank O’Hara, from “Here In New York We are Having a Lot of Trouble with the World’s Fair”

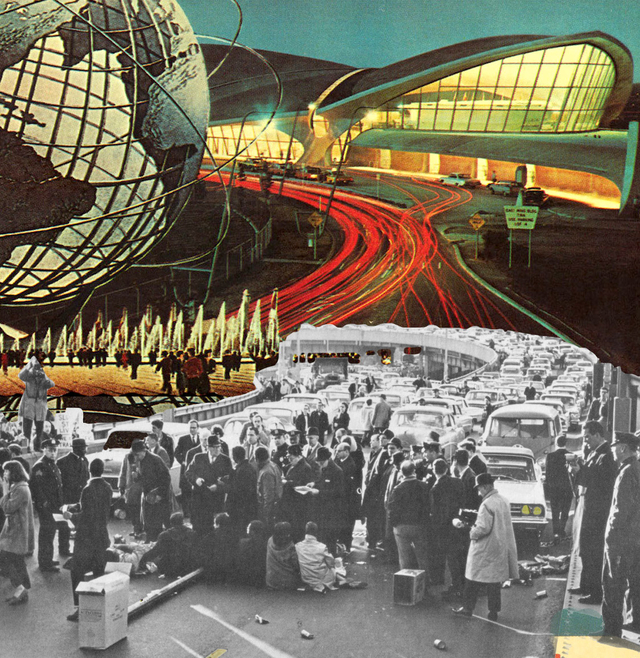

Trouble in Tomorrow-land

It was supposed to be perfect: a paean to free enterprise, technology, and the progress of freedom made tangible in the form of consumer convenience. Built on the refuse of the Corona dump—F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “valley of ashes”—the 1964 New York World’s Fair would be, “master builder” Robert Moses hoped, “an Olympics of progress and healthy rivalry, a vast Colosseum dedicated to new friendships… the hopes and aspirations of a new world.”

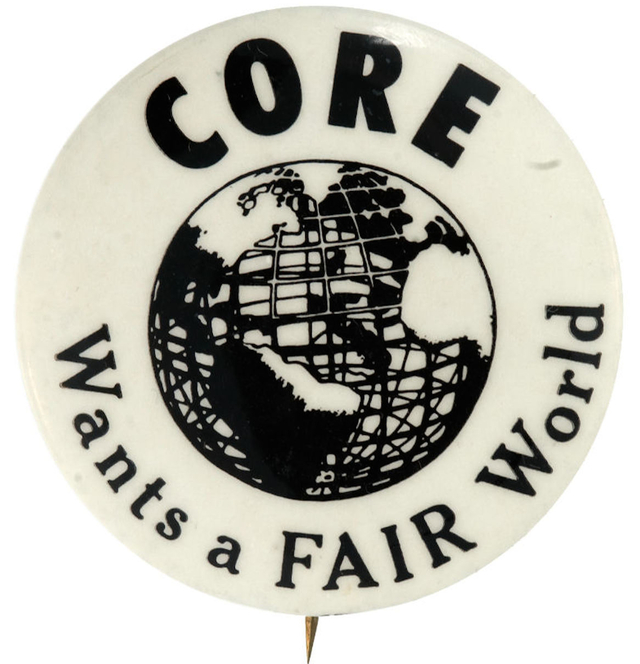

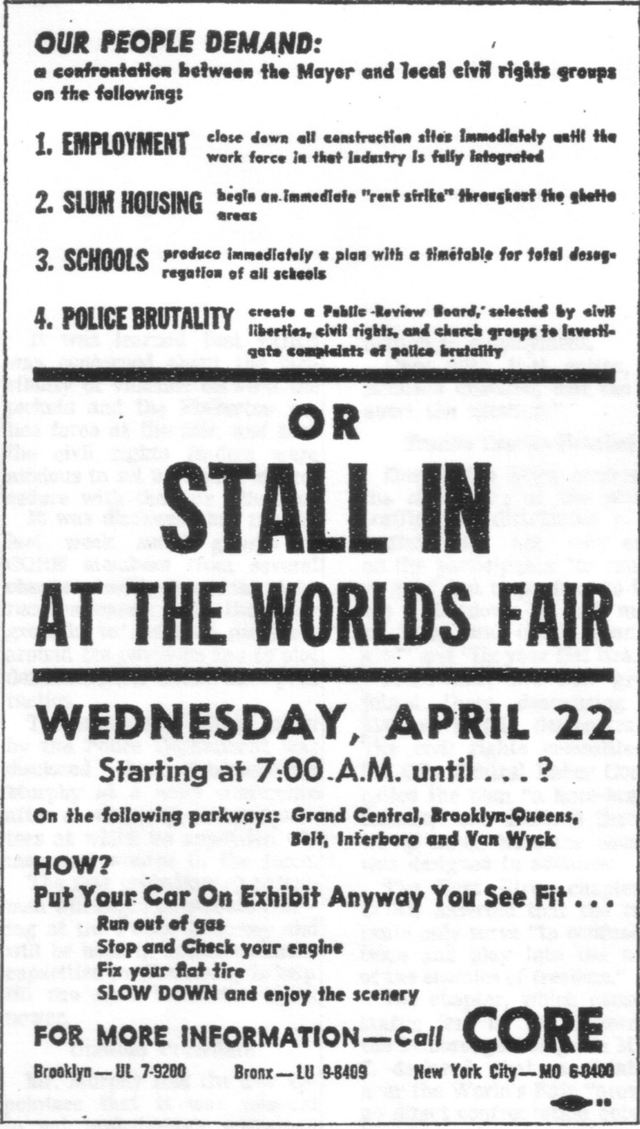

But with less than a month to go before opening day, the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) announced plans for a fair exhibit of their own: hundreds, if not thousands, of stalled cars on the highways leading to the fairgrounds, tying up traffic for hours and preventing hundreds of thousands of eager fair patrons from entering the gates. Isiah Brunson, the soft-spoken 22-year-old and chairman of Brooklyn CORE, explained it this way:

We are having the stall-in to shut off traffic at the World’s Fair because the city and the state have seen fit to spend millions and millions of dollars to build the World’s Fair, but have not seen fit to eliminate the problems of Negroes and Puerto Ricans in New York City.

Unless the city of New York made rapid progress on long-standing demands for quality, integrated schools, non-discrimination in housing and employment, and a civilian review board to oversee cases of police brutality in black neighborhoods, CORE would choke off the arterial highways connecting the city to the Fair—and thus, the city to much anticipated tourist dollars.

Poster for Brooklyn & Bronx CORE World’s Fair ‘Stall-In.’ Congress of Racial Equality

The local and national press pounced on the story, devoting column inch after column inch, day after day, to the proposed protest—making the stall-in one of the best publicized protests never to occur. Commentators were quick to condemn the protests as unreasonable, dangerous, and even violent; angry letters to the editor poured in. Politicians were not far behind in their condemnations. Senators Hubert Humphrey and Thomas Kuchel warned in a joint statement that “illegal disturbances, demonstrations which lead to violence or to injury, strike grievous blows at the cause of decent civil rights legislation.” Richard Wagner, then Mayor of New York, likened the protests to a “gun held to the heart of the city,” which threatened more harm than “anything that Dixiecrat Senators can do in Washington, or that the forces of bigotry can do in this city.” A bit too eager to seize on public rifts in the civil rights movement, all were quick to distinguish the majority of “responsible Negro leaders” who remained true to nonviolence and kept their eyes on the prize (the Civil Rights Act) from those irresponsible few willing to bring “unnecessary inconvenience to others” to get their way—or at least get their names in the papers.

All this press brought notoriety and publicity to the protest, but also ensured a swift response from the city and the World’s Fair Corporation. Robert Moses’ statement to the press was characteristically tough and terse: “The fair will not become a stage for irresponsible interference with visitors, secondary boycotts and demonstrations not related to the proper conduct of the fair.” Behind the scenes, meanwhile, in conjunction with the New York Traffic Commissioner Henry Barnes, a new law was swiftly passed stipulating a maximum penalty of thirty days jail time and a $50 fine for any driver who might run out of gas on the highways of New York. The city also promised to keep a massive force of police, tow trucks, and a helicopter airlift at the ready along the major Fair throughways—a testament to how quickly and effectively money, time, muscle, and means could be put together by the ruling powers in New York when there was the political will to do so.

And thus it was: though it was quickly backed by CORE chapters in the Bronx, Harlem, Manhattan, Long Island, and Yonkers, along with college chapters at Queens College and Columbia University, the protest was not to be. National CORE opposed the protest, on the grounds that it violated CORE’s established Rules for Action by not focusing in on a clear target, and prevented other chapters from pursuing more traditional protest tactics at the Fair (the picketing of particular pavilions, for example, which had been hastily planned by National CORE as an alternative to the stall-in). When the Brooklynites proceeded with their plans anyway, in defiance of National Chairman James Farmer’s explicit instructions, the chapter was formally suspended. Without the backing—and the logistical capacity—of the national organization, the local chapters had little ability to pull off a 2,000-car stall-in. Perhaps more to the point, the imposition of criminal fines and jail time for potential stallers-in likely had a chilling effect on those would-be volunteers looking to put their cars, and their cause, on exhibit.

The morning of the 22nd, under the gray and drizzling New York skies, journalists awaiting a massive highway tie-up found—to their rather smug delight—few cars and little traffic. At the fairgrounds, a rather orderly procession of several hundred activists organized by Farmer picketed several state and corporate pavilions, and were arrested; at President Johnson’s speech during the opening ceremonies, a less orderly band of college students heckled, taunted, and chanted their way through the President’s claim that “We”—Americans, that is—“do not try to disguise our imperfections and our failures. No other nation in history has done so much to correct its flaws.” But a stall-in there was not.

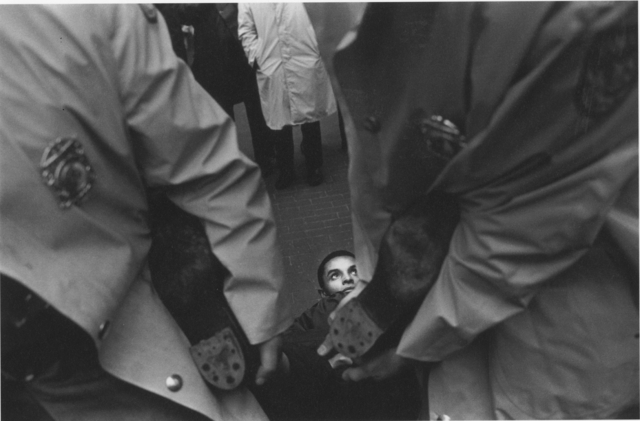

An anonymous activist at the CORE protest. Congress of Racial Equality

On the other hand, neither were there huge crowds waiting to partake in the Fair’s many futuristic wonders. Although Moses had anticipated opening day would bring a quarter million patrons through the Fair gates, by the mid-afternoon, scarcely more than 60,000 had visited Tomorrow-land. The bad weather was undoubtedly a factor. But so was the press around CORE’s protest. The stall-in may have fizzled, but it hardly failed.

Present tense, Futurama perfect

However radical, the tactic of the stall-in did not represent a total break with what came before it. In his keynote address at the annual convention of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference—an organization defined by its steadfast commitment to nonviolence, and perceived by the news media and the public as more moderate than radical—Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker all but suggested a nationwide stall-in. In the wake of the 1963 Birmingham church bombings (and subsequent violence) that killed six children, and with a comprehensive civil rights bill still more than a year off, it seemed like such means might ultimately be necessary. “Is the day far-off that major transportation centers would be deluged with mass acts of civil disobedience; airports, train stations, bus terminals, the traffic of large cities, interstate commerce, would be halted by the bodies of witnesses nonviolently insisting on ‘Freedom Now’?” Such a protest, had it ever come to pass, would have far outstripped the World’s Fair protest both in radicalism and in levels of disruption. Moreover, as numerous Southern congressmen were keen to point out in the midst of the stall-in uproar, the seemingly tame tactics of the Southern civil rights movement—sit-ins, pray-ins, marches, boycotts—were at least close cousins of the stall-in, if not more intimately related. From the perspective of those most affected by it, good civil disobedience is always experienced as disruption.

But it wasn’t just about the tactics. Everyone—politicians, journalists, Fair officials, ordinary citizens (not all of them white), and even a few of those other civil rights leaders who publicly condemned Brooklyn CORE—seemed baffled, and not a little bit angry, about the very idea of protesting the World’s Fair at all, stall-in or otherwise. The site itself seemed oddly off-limits. When the stall-in failed to materialize, the protestors who did show up at the Fair received no small measure of the public ire—the National CORE-led pickets no less than the chanting youths at Johnson’s speech. “The World’s Fair has not been discriminating against anybody,” complained one columnist in the Times. “It is not a seat of government. It has no authority to bring about civil rights reforms or correct wrongs in the social order. Its theme, ‘Peace through Understanding,’ in itself suggests sympathy with the just aspirations of all peoples. To make it the scene of various demonstrations, as Brooklyn CORE and perhaps other groups apparently intend to do, is to send the marchers to the wrong address.”

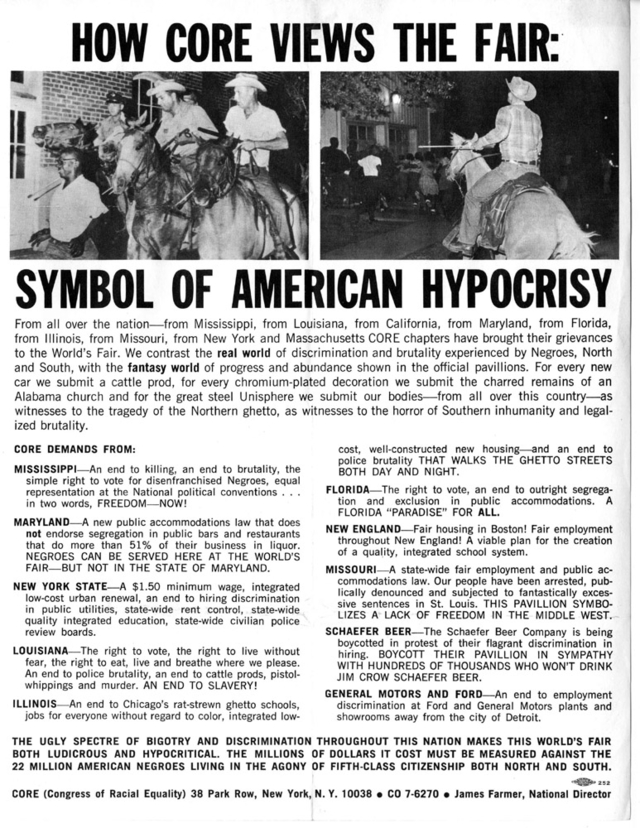

National CORE 1964 World’s Fair Flier. Congress of Racial Equality and Elliot Linzer, Queens College Civil Rights Archives

It doesn’t take an extraordinary feat of imagination to see it otherwise, though. If the New York World’s Fair seemed to break with an established pattern of civil rights protest venues, it nevertheless offered no shortage of reasons—from the practical to the purely symbolic—to think it an obvious choice for a CORE demonstration.

First, it is not exactly accurate to say that civil rights groups had no claim of discrimination against the Fair, or that the Fair had no power to bring about the desired reforms—particularly in the area of employment. Several civil rights groups, including the NAACP, had been battling Moses since the early days of Fair development over black and Puerto Rican employment, to which Moses reacted in his usual way: by dismissing them as the bogus claims of agitators and “professional integrationists,” which he would not or could not address. The Fair was also a 5-year-long public works project of unprecedented scale, requiring the cooperation and manpower of the unionized building trades—the same industry that Brooklyn CORE and other New York groups had been struggling in vain to integrate.

However, it was the symbolic power of the Fair and the image of the future it projected—not just their direct discrimination claims against the unions, nor the undoubted potential of the Fair as a media event—that captured the activists’ attention. The New York City chapters of CORE had been struggling for years to make the reality of life in the ghettos of Bedford-Stuyvesant and Harlem visible for the rest of the city’s residents through rent strikes, school boycotts, and—in a move that now appears as a clear precursor to the stall-in—trash dumps at Borough Hall and on the Triborough Bridge, the latter of which tied up traffic for 20 minutes by attempting to show the angry motorists a small slice of life in the ghetto. The Fair presented a perfect opportunity: as Herbert Callendar of the Bronx chapter of CORE explained, “The World’s Fair portrays an image of peace, tranquility and progress—the American dream. We want to show that there is also an American nightmare of the way Negroes have to live in this country.”

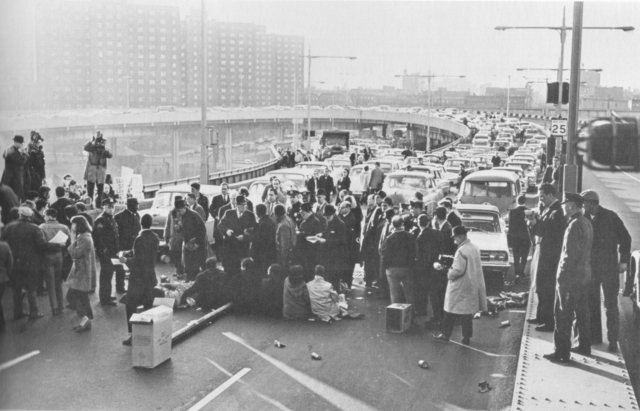

The CORE sit-in on the Triborough Bridge. Meyer Liebowitz, via CORENYC.org

Indeed, it is hard not to appreciate the perfect irony of creating a traffic jam as a protest of Robert Moses’s Fair. Moses was the man who believed cities to be “created by and for traffic” (and who wasn’t afraid to bulldoze a few neighborhoods to prove it). He was the mastermind and architect behind New York’s congested highway system, and the urban planner associated with the notorious “urban renewal” and “slum clearance” programs of the 1950s (termed “Negro removal” by author James Baldwin).

On its own, the World’s Fair earned an early reputation for being the sort of traffic disaster to which the stall-in could only aspire, thanks to construction on the fairgrounds and on the surrounding highways. In 1962, Time Magazine claimed that, by that point, the Fair was renowned mostly for the “bumper-to-bumper embolisms the highway expansion program is causing in the borough of Queens”—a project that cost hundreds of millions of dollars, but famously turned Queens into “the world’s biggest parking lot.” Even after construction had been completed, the Fair was automobile- and highway-centric, angling for middle class patrons coming in by car, rather than the local working-class on the 7 train.

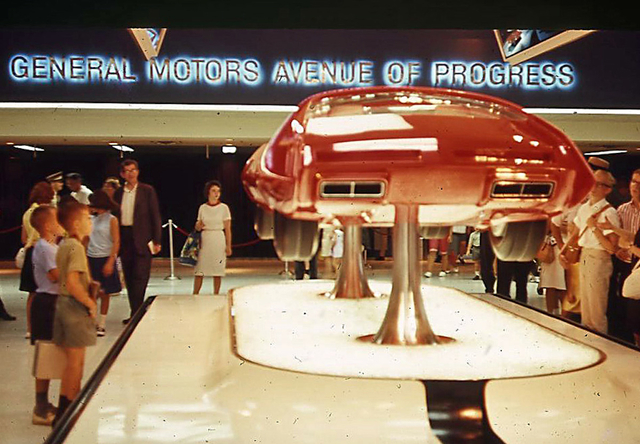

Inside the fairgrounds, what would be criticized as the “Hard-Sell Fair”—a place defined by its “tacky, plastic, here-today-blown-tomorrow look, as if it were a city made of credit cards”—made the contrast between the American dream and its nightmare shadow more spectacularly visible. The Fair was a celebration of an infinitely consumable—but ultimately disposable—world; its dozens of buildings made to last two years and no longer, before being demolished again (at a considerable cost). There, General Electric’s “Carousel of Progress” celebrated the conquering of the home by household electronics while the Ford Motor Company’s “Magic Skyway” took patrons on a journey from “the world that was” to the “world that will be” via Mustang convertible. And, most poignant of all, at the Fair’s most popular exhibit, General Motors’ Futurama, spectators witnessed the wonder of a highway-ringed “City of Tomorrow,” a “utopian metropolis” free from “slums or parking problems,” while in a far-off jungle, a “road-builder” brought “progress and prosperity” by clear-cutting forests while leaving an elevated highway in its wake.

Promotional video for General Motors’ Futurama ride.

Denizens of Bed-Stuy, Harlem, the Bronx, and Queens might well have recognized the “road builder” as none other than Robert Moses—though, in their experience, prosperity was not forthcoming, and slums remained very much a reality. And so with the entirety of the future according to the World’s Fair: it represented a temporality of present and future progress both out of step with the reality of inequality in 1964 America, and simultaneously implicated in it. And perhaps this is one reason why the stall-in was as controversial, divisive, and upsetting as it was: it threatened to interrupt a certain imaginary of progress, democracy, and freedom (wide open as the highway, headed toward the infinite horizon) with the perpetually, systemically-stalled reality of racial injustice, in which there were no innocent bystanders.

In the midst of the national outcry over the stall-ins, these powerful intuitive and metaphorical connections were all but obscured. Public statements from a few prominent figures in the civil rights movement drew attention to these layers of meaning—the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., and even James Farmer participated—but seemed unable to shift the discourse. Ironically, it was Police Commissioner Michael Murphy, while criticizing the “shocking and disturbing” protests at the Fair, who said it best: President Johnson, alongside tens of thousands of fairgoers, had come “to the world of fantasy” only to “[encounter] the world of fact.”

We pay a lot for our entertainment

By its own design, the Fair was practically ready-made for (over)-interpretation—the Avenue of Progress actually intersected with the Avenue of Commerce! The World’s Fair was meant to represent, exhibit, predict, and promote. It hocked visions of progress as product-placement, and spoke in the honeyed tones of a 646-acre advertisement for better living—slum-less, traffic-free and strangely un-peopled city of the future, all in the midst of the slum-ridden, traffic-clogged, and population-dense New York City of the present. In Robert Moses’s own terms, the World’s Fair had to be “part theater, part traveling carnival, part insubstantial pageant and part permanent park.” More than a few snapshots offer themselves up as perfect metaphorical encapsulations of the moment—of the Fair or its host city, of civil rights and race relations, of America in the mid-sixties, quickly losing its idea of itself. The Fair is a thing overburdened by metaphor.

For that reason, if not for others, I should ignore the temptation to punctuate this essay with a metaphor. But I find that I cannot; there are just too many good ones on offer. And for this particular story about the clash between the America packaged and sold by the Fair and the one protesting at its gates, I can’t resist the animatronic Abraham Lincoln standing in the Illinois Pavilion. In my defense, I wouldn’t be the first. Writing a month after the Fair’s opening, John Skow (underwhelmed, and apparently with tongue firmly in cheek) deemed the mechanical Lincoln “the very spirit of the New York World’s Fair. Not to see the animated Emancipator,” he continued, “is to fail to understand what the World’s Fair is about.”

Designed and created by engineers at the Walt Disney Corporation (“Imagineers” is the unfortunate term of art) for the ludicrous cost of half a million dollars, a mechanical simulacrum of the Great Emancipator was not only summoned from beyond the grave, but was reincarnated as a Cold War liberal. During the 1964 and 1965 seasons, spectators at “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln” watched with amazement as a stunningly life-like Lincoln rose from his seat, turned his head ever so slightly, and delivered some sober words of wisdom: a short oration on liberty stitched together from excerpts of several different speeches. In a booming baritone, the Lincoln-bot intoned:

The world has never had a good definition of the word liberty, and the American people, just now, are much in want of one. We all declare for liberty; but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing.

Walt Disney’s “Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln.”

These words, from an 1864 speech Lincoln gave in Baltimore, are true enough to history—at least if your main concern is that Lincoln actually said them. But context matters, and in this case the words left out of the “animated Emancipator’s” speech are far from incidental. The real Lincoln, the historical Lincoln, speaking in the midst of the Civil War and on the heels of the massacre of black troops and their officers at Fort Pillow, went on to explain his reflections on the meaning of liberty in the following terms, redacted from the World’s Fair rendition:

The shepherd drives the wolf from the sheep’s throat, for which the sheep thanks the shepherd as liberator, while the wolf denounces him for the same act as the destroyer of liberty, especially as the sheep was a black one. Plainly the sheep and the wolf are not agreed upon a definition of the word liberty; and precisely the same difference prevails to-day among us human creatures, even in the North, and all professing to love liberty. Hence we behold the processes by which thousands are daily passing from under the yoke of bondage, hailed by some as the advance of liberty, and bewailed by others as the destruction of all liberty. Recently, as it seems, the people of Maryland have been doing something to define liberty; and thanks to them that, in what they have done, the wolf’s dictionary, has been repudiated.

The full speech performed at the show was free of any reference to slavery and the American racial order. Instead, the Fair’s Lincoln cautioned his 1964 audience of the dangers of enemies within, exhorted fierce reverence for the rule of law, and urged steadfastness in the face of “false accusations” and the “menaces of destruction.” Strung together just-so, Lincoln’s words were a salve to the troubled Cold War mind—a firm endorsement of staying the course, and a reassurance against the legitimacy of the tumult in the streets.

Confronted with this strange, transhistorical robot, I cannot help but compound one metaphor with another, and recall the image of the mechanical Turk that opens Walter Benjamin’s famous “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Benjamin’s automaton is dressed like a Turkish chess player and controlled by a “wizened” master chess player, a dwarf hidden from view through an optical illusion. The game is rigged; the automaton is “to win each time” by selling his opponent the idea of progressive time: reason made perfect through human history, and a future triumphant, unburdened by the wreckage of past and present. This is, of course, the dream of Moses’s Fair, Disney’s Lincoln, and midcentury American liberalism. But it is also a myth. “[A] storm is blowing from Paradise,” Benjamin tells us later in Thesis IX—a storm which propels the “angel of history” headlong “into a future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

This is the poignant lesson urged by the stall-in protest that never was: what we call progress has been, in some not-so-distant corners of our polity—just outside the fairgrounds, as a matter of fact—a human disaster. The “pile of debris” left by CORE on the Triborough Bridge and on the steps of Borough Hall appears, no less than the stall-in, one small attempt to make visible that fact, to force a confrontation with it. As Benjamin suggests, we ignore it at our own peril.

Of course, none of this changes the fact that the Fair was enjoyed and indeed beloved by a record-making 50 million visitors over the course of its two seasons, throughout which Disney’s Lincoln and GM’s Futurama were crowd favorites. Lawrence Samuel is right to point out (as he does in his recent book The End of Innocence) that despite the harsh words of cultural critics about the Fair’s rampant commercialism, despite its legacy as a financial failure, despite its outright denial of valid claims to racial justice—in the popular memory, the Fair lives on as “an experience that most visitors found thoroughly enjoyable if not enthralling, that sparked imaginations and reshaped people’s vision of the world.”

My point is not that people were wrong to think so, or that they should have seen through the corporate heroics or the sanitized Lincoln (though I certainly think that we should). At its core, the World’s Fair was entertainment, and entertaining it was. But there is always a cost that comes along with creating and selling a pristine version of past, present, and future; there is a cost that comes with being seduced by it, believing we can simply buy a better future or trust in technological innovation to invent one for us, in spite of the evidence of the troubled present and the wreckage of the past. Despite President Johnson’s (no doubt) earnest words at the opening ceremonies—forecasting for the future America an “[unwillingness] to accept public deprivation in the midst of private satisfaction”—the Fair itself seemed to speak more loudly of our willingness, our eagerness, to do just that.

It is as Frank O’Hara claimed: we pay, sometimes dearly, for our entertainment.

Recommended Reading

Bletter, Rosemary Haag et al. Remembering the Future: The New York World’s Fair from 1939-1964. New York: Rizzoli, 1989.

Wilder, Craig. A Covenant with Color: Race and Social Power in Brooklyn. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000.

Samuel, Lawrence. The End of Innocence: The 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2010.

Purnell, Brian. Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings: The Congress of Racial Equality in Brooklyn. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2013.

Tirella, Joseph. Tomorrow-Land: The 1964-1965 World’s Fair and the Transformation of America. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2014.