Monstrous News: the Futures of the Mistris Parliament Plays

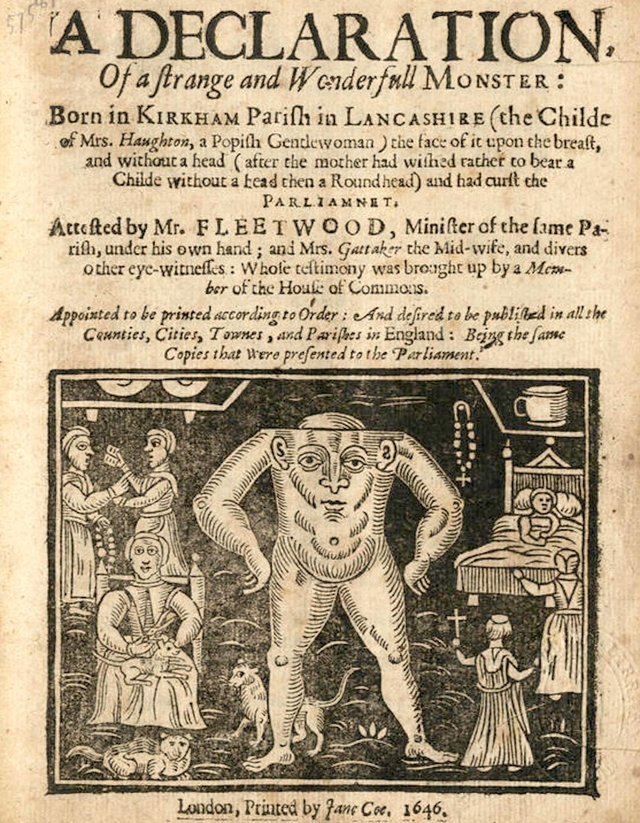

Literary visions of bad futures, from “monstrous births” to rebellious parliaments, were a potent polemical tool in the early centuries of print. Detail from the frontispiece of Anonymous, A Declaration of a Strange and Wonderull Monster (London, 1646)

In a dark room in an obscure corner of London, Mistris Parliament is giving birth to England’s future. Her offspring, the Child of Reformation, is destined to overrun the nation with meddling. She struggles, sweats, and vomits. Her visitors and attendants cannot relieve her suffering. The birth pangs of her monstrous body, both female and legislative, are a foul clarion call for the embattled king’s loyal supporters. The future is coming. It is disgusting and transgressive; it must be avoided at all cost.

This scene is from Mercurius Melancholicus’s Mistris Parliament Brought to Bed of a Monstrous Childe of Reformation, a remarkably brief play issued as the first installment of the Mistris Parliament series published in 1648. The Second English Civil War (1648-1649) was well underway, the reigning sovereign King Charles I was imprisoned in Parliamentary custody on the Isle of Wight, and England had been embroiled in civil conflict for over a decade. These events, naturally, led many writers to consider the immediate future of the polity.

If the future of a nation is its children, a monstrous birth is infelicitous at minimum and damning at worst. Authors of texts like this one asked their readers to imagine good, bad, and sometime even disgusting futures to galvanize support for causes ranging from King’s release to changes in tax policy. And like the Mistris Parliament plays, they display the increasingly imaginative uses of sensational, national, and reproductive futurity in popular political writing. These visions of the future—positive or negative—were yoked to worldviews that tracked time according to providence and eschatology, cyclical logic, incremental decay, or, most innovatively, for the seventeenth century, progressive development. The archive of literary pamphlets from the mid-seventeenth century bears witness to this range of historical perspectives, from apocalyptic visions to local satires, triumphalist allegories, and cautionary tales. Whichever perspective governed the historical logic of a particular publication, one through line remained stable: The future of the nation was at stake.

Historians still debate the causes and effects of the English Civil Wars, which raged from 1642 to 1651 and ended with King Charles I losing his head and Oliver Cromwell and his “New Model Army” in nominal control of a restive populace. One of their most well-documented results, however, was a simultaneous lapse in press oversight and a boom in the publication of political writing. By 1648 new titles were flooding booksellers’ stalls, especially short books, polemics, pamphlets, and petitions. Newsbooks, an early form of the modern newspaper, were issued weekly or bi-weekly under the aegis of partisan “Mercurii” like Mercurius Britannicus, which promoted Parliament’s agenda, and the Royalist Mercurius Melancholicus, which went above and beyond to support Charles. Royalist Mercurii like Melancholicus, Elencticus, and Pragmaticus all also experimented with literary newsbooks and pamphlets perhaps to accompany and support their more purely journalistic efforts.

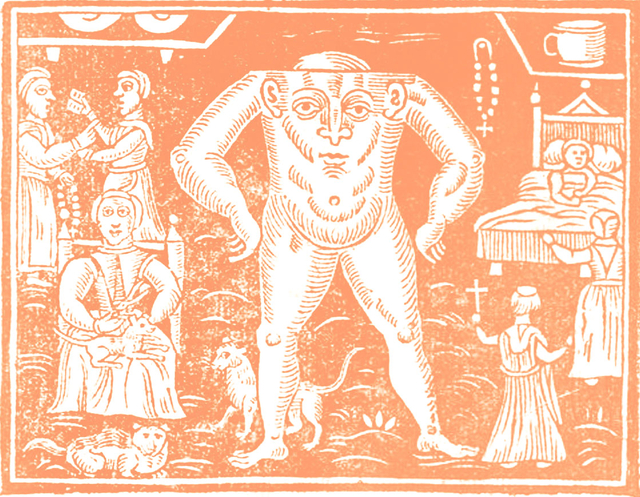

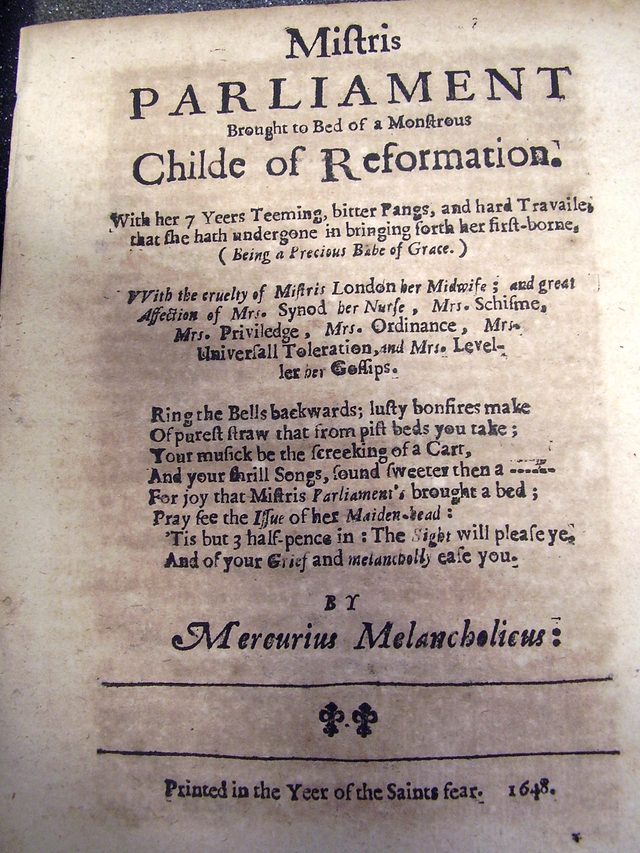

The Mistris Parliament plays are true products of the innovation and mayhem of the mid-seventeenth-century print market. Lois Potter quips that Melancholicus “exploited its illegal, hand-to-mouth status,” in the lone modern edited edition of the Mistris Parliament series. Instead of listing publisher, printer, and bookshop on its title page, Mistris Parliament I states that it was “Printed in the Yeer of the Saints fear. 1648.” The only convention it abides by is the date.

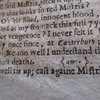

Title Page, Mercurius Melancholicus, Mistris Parliament Brought to Bed of a Monstrous Childe of Reformation. University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts. Call number Rare Book Collection DA 412 1648 M531 1648, 2014

The journalists behind Melancholicus decided to dramatize, rather than report, their discontent in the Mistris Parliament plays. This group of poet-journalists may have included John Crouch, George Wharton, Samuel Sheppard, John Cleveland, Samuel Butler, and the notorious Marchamont Nedham, all authors working for the prominent Royalist newsbooks in the spring of 1648. Each of these men had vested interests in the political, theological, and commercial outcomes of ongoing civil conflict: The Mercurii had skin in the game and fair and balanced reporting was neither the goal nor the result of their journalistic efforts. And they took a chance by circulating a short play instead of another genre of print polemic, like a pointed prose animadversion. It looks like their bet worked out. If Mistris Parliament I hadn’t sold well, Melancholicus never would have issued a follow-up, let alone a series in four parts.

Newsbook plays like the Mistris Parliament series circulated in the same printed format as other political works from this era. Mistris Parliament I looks like this:

The HathiTrust/Google digital copy of the Columbia RBML original of Mistris Parliament I

After the text was printed on a single sheet of paper, these pamphlets were made by folding the printed sheet of paper into four parts, trimming the edges, and stab-stitching the folds together to produce a slim volume. To keep these brief books, owners would bind them together in a sammelbände, with similarly-sized or thematically-related materials, and store them in their personal libraries. But political print ephemera were also discarded, used for scrap paper, or repurposed as toilet tissue, a trend “Bum Fodder” and other ballads affirm in their verses. These short-lived pamphlets recorded the news: the day-to-day events of a nation at war with itself, the debates in Parliament and among the troops, the grievances of the capital and the countryside. Reaching beyond the journalistic present, some Mercurii imagined scenes—like the birth of a child of reformation—to distinguish themselves in the crowded market and perhaps avoid an excremental fate.

For Melancholicus, literary visions of bad futures were a potent polemical tool. Would you want a Child of Reformation transforming your nation? Royalist news writers perpetuated this subgenre of speculative political writing by dramatizing other abhorrent (to them) political futures where Oliver Cromwell became King of England and prominent members of Parliament communed with demons. Unlike their Parliamentarian and sectarian counterparts, who actively promoted new models for political and social organization in their pamphlets and newsbooks, Royalist journalists were far more likely to use hyperbole, demonology, and other assorted scare tactics to descry these innovations. After all, they were promoting the status quo—a return to time-worn tradition, monarchical political organization, and the world as it should be rather than “the world turned upside down” imagined by their radical contemporaries. The Mistris Parliament plays document the adventures of Mistris Parliament, a grotesque feminized depiction of the corporate governmental institution. To inspire horror in loyal partisans Mistris Parliament, as we have already seen, gives birth to a monstrous reforming child in the first play, and in the subsequent issues she and her hellish offspring wreak havoc.

The poem prefacing the play makes the portentous claim that “Our miseries then shall soon be past, / And our sick land be well” once the scourge of Mistris Parliament and her progeny are wiped from the land. The future is not only a political disaster allegorized through the dual vectors of monstrosity and misogyny, but it is sick, even nauseating. The tense birthing room of early modernity is a liminal space between life and death, between future progeny and past fertility. The only difference here is that the birth is something the text’s authors would rather avoid.

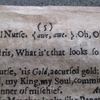

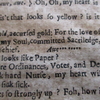

The future even sounds bad. Mistris Parliament I renders the violent noises and actions that accompany birth with onomatopoetic phrases and suggestive typography. When Mistris Parliament is nauseated she asks for a bowl to puke in and the text renders her vomiting with the exclamation:

} hawe } hawe. } ….

In between bouts of sickness Mistris Parliament and her attendants discuss her excretions of blood (the blood of the people she unjustly killed), choler or yellow bile (the gold she has taken from England’s citizens), and paper (the ordinances votes and declarations she has issued). Mistris Parliament’s suffering noises punctuate these exchanges. She {awe.}s, she {awe, awe.}s, and she Awe……s sighing, heaving, vomiting, and giving birth. Her crimes are writ large in her raucous suffering: unjust executions, widespread theft, and paper-pushing reform.

Only when I carefully examined the original printed texts of these plays did I notice the repulsive and explosive typography that accompanies Mistris Parliament’s monstrous labor. Because of my training as a literary scholar, I think a lot about how genre, form, and typography affect both early modern and twenty-first century readers. Mistris Parliament’s onomatopoetic and typographic nausea raises the question: How does this visually complex and comically scatological typography affect readers? As a reader who also rejects the rise of Parliamentary power, do you wretch along with Mistris Parliament out of horror at the assembly’s advances? Do you laugh? Are you repulsed enough by her to actively engage in ongoing political conflict in a new way? Do you feel reassured in your positions? Do you buy the sequel? Do you use this slim book as toilet tissue and return to more serious pursuits? Or do you take up arms and try to prevent the birth of this hideous disaster of reform? What actions might reading this extravagantly political play motivate?

Of course, after all the aweing and hawing the birth itself is still delayed a few pages. In the midst of her labor, Mistris Parliament composes a declaration confessing her many crimes—from perjuring her “Oath of Allegiance” to the crown to stealing the nation’s property “by the instigation of the Devil, and against the Lawes of our Soveraign Lord King CHARLES.” Worst of all, perhaps, is her confession of topsy-turvy logic: “Instead of Reforming J have Deformed and in stead of repairing J have pulled down; Which hath occasioned all these miseries to fall upon me.” But after all this writing, witnessing, praying, and confessing, the child is born:

Whils’t she was speaking the room was strangely overspread with darkness, the candles went out of themselves, and there was smelt noisome smells, and heard terrible thunderings intermix’d with wawling of Catts, howling of Doggs, and harking of Wolves against the windows flew ill boading screetch-Owles, Ravens and other ominous Birds of night, that strook a great terror to the hearers; at the same time Mrs. Parliament, was miraculously delivered of a Monster of a deformed shape, without a head great goggle eyes, bloody hands growing out of both sides of its devouring panch, under the belly hung a large bagge, and the feet are like the feet of a Beare.

This unruly child, part-human and part-beast, enters the world ready to “devour” all before it. Beyond the horror of her typographically-marked sounds, Parliament’s progeny is poised to disrupt the nation even more than its monstrous mother’s thefts and reforms. Playing into pervasive tropes of misogyny and biology, the monstrous child will continue Parliament’s work, thus rendering the state unrecognizable to Royalists like Melancholicus. By perpetually reconfiguring and undermining conventional structures of governance and rule, the babe of grace will destroy the churches, assemblies, and courts that Melancholicus hopes to restore.

From the teeming multitudes embodied in Mistris Parliament—a female body representing the people of the nation, full of paper and gold, defined by blood and womb—a lone child harboring a singular future is born. It is part human, part monster, and all ideology. This is monstrous news.

“How ugly will it appear in the Chronicles of after times?” Melancholicus wonders at the end of the play. How ugly, indeed. The hawing and vomiting that accompany the birth of a monstrous future may fade, but its echoes linger in the archive. Mistris Parliament’s {awe.}s are still ugly, though perhaps differently ugly than Melancholicus intended.

Further Reading

Lois Potter, Secret rites and secret writing: Royalist Literature, 1641-1660. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Joad Raymond, The Invention of the Newspaper: English Newsbooks 1641-1649. Oxford: Clarendon, 1996.

Nigel Smith, Literature and Revolution in England, 1640-1660. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

Susan Wiseman, Drama and Politics in the English Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.