Quests for Fire: Neanderthals and Science Fiction

Humans have been playing with fire for a very long time. Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Fire, 1566, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (via Wikimedia Commons)

The Quest Begins: Neanderthals Meet Science Fiction

In 1856, workers at a limestone quarry in the Neander Valley of Germany turned over a curious set of skeletal remains to a local amateur naturalist, Johann Carl Fuhlrott, who, in turn, delivered the bones to famed anatomist Hermann Schaffhausen. The bones, described as Neanderthal 1 (or Homo neanderthalensis), showed a species very much like our own—yet different enough in anatomical detail to warrant a new taxonomic designation. This new “almost-human” species offered the nascent discipline of paleoanthropology fantastic specimens for study, filling out the fossil record. Archaeological excavations began in earnest across Europe to recover more such fossils, particularly in southern France during the first decade of the twentieth century. These new sites yielded a plethora of Neanderthal fossils.

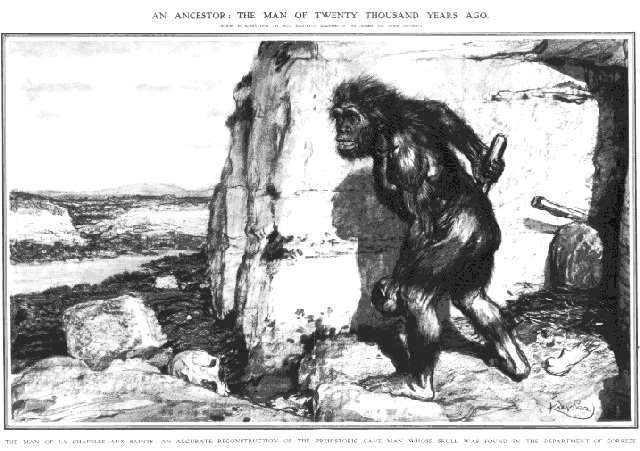

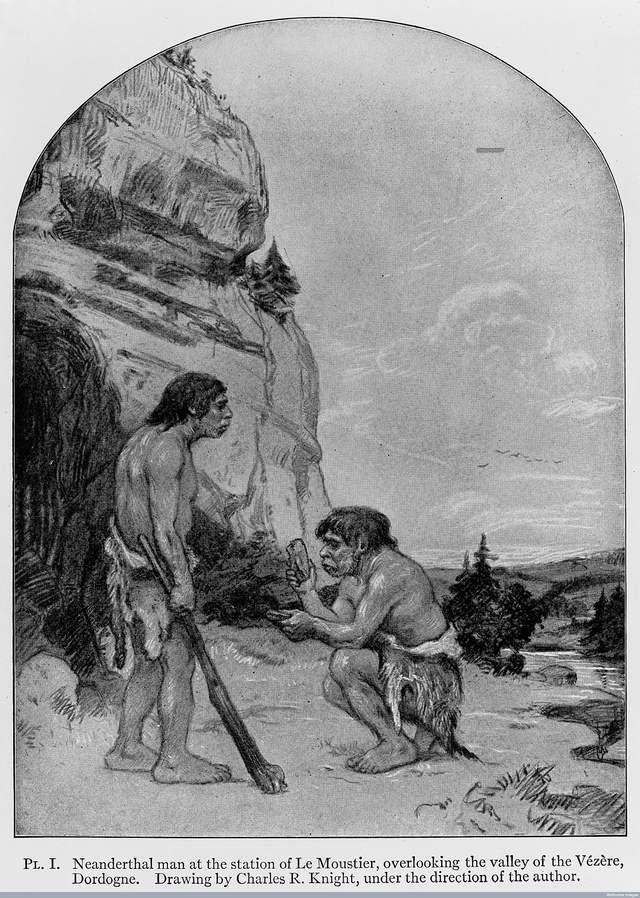

In 1908, Amadee Bouyssonie, Jean Bouyssonie, and L. Bardon published the results of their excavations at La Chapelle-aux-Saints, a cave site in southern France. They described a fossil skeleton known as the Old Man: a skull, jaw, vertebrae, several ribs, most of the arms and legs, and smaller bones of the hands and feet. The print media sensationalized the Old Man and within a year he had appeared in the pages of The Illustrated London News and been painted by eminent paleo-artist Charles Knight. Fragments of additional Neanderthal skeletons were recovered in 1909 at the Dordogne sites of Le Moustier and La Ferrassie, effectively doubling the number of known Neanderthal specimens. Between 1848 and 1914, the field had identified more than fourteen sites across the globe that yielded Neanderthal fossils and the remains of other human ancestors—ancestors like Java Man from Trinil; Homo heidelbergensis from Germany; Cro-Magnon near Bonn; and even “ancestors” like Piltdown. By 1914, paleoanthropology recognized five species of human ancestors, two sub-species, and the tangible evidence of humanity’s antiquity proved utterly captivating.

“An Ancestor: The Man of Twenty Thousand Years Ago,” by Franz Kupka Amédée Bouyssonie, Jean Bouyssonie, and L. Bardon, “Découverte D’un Squelette Humain Moustérien À La Bouffia de La Chapelle-Aux-Saints (Corrèze),” L’Anthropologie 19 (1908): 513-18.

Charles Knight under the direction of Henry Fairfield Osborn, (1915.) “Neanderthal man at the station of Le Moustier, overlooking the valley of the Vezere, Dordogne.” Printed as front piece to Men of the Old Stone Age: Their Environment, Life and Art. Wellcome Images

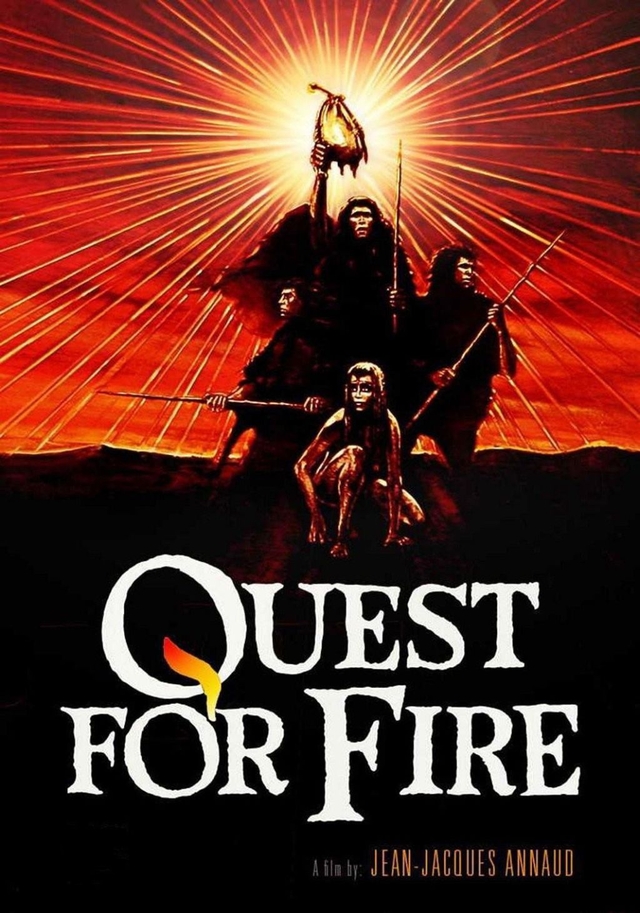

In addition to exciting anthropology and public imagination, these new Neanderthal finds provided fodder for science fiction—a young literary genre on the rise. The worlds of Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and other early sci-fi authors teemed with unexplored geographies, Darwinism, mechanical inventions and the material cultures of science. The caves and archaeological sites of Europe provided a perfect backdrop for speculative fiction. The almost-human Neanderthals became the perfect alien character—so much like us, but also safely different. As more and more Neanderthal fossils entered the published record, questions about who they were, how they lived, and the implications of such a human-but-not-quite human species began to appear in a variety of media. French author J.H. Rosny captured the zeitgeist with his 1911 novella Quest for Fire. “At the very dawn of man’s existence,” Rosny wrote:

Rival tribes clash in a life-and-death struggle for the possession of fire. When their life-sustaining fire is lost during an attack by marauding Neanderthals, three courageous warriors embark on a perilous journey into the vast uncharted world beyond their tribal land—a journey that takes man a giant step into the future.

The novella takes the state of anthropological knowledge post-La Chapelle and runs with the “what if” scenarios that such an evolutionary history suggested. Early twentieth-century scientists, particularly Marcellin Boule, described Neanderthals as brutish and inherently more primitive than the more “gracile” humans. Others were less overt in their Neanderthal prejudices—they saw Neanderthals as a sad and cautionary evolutionary story about a species unable to successfully evolve. Early dioramas and reconstructions in the 1910s-1930s displayed hunched individuals with exaggerated arms. Here, the dioramas seemed to say, was a clumsy species that couldn’t evolve to compete with the technological and cultural “superiority” of modern humans. The artist Charles Knight even wrote that he felt sorry for Neanderthals. Quest for Fire encapsulated this view of Neanderthals as pitiable primitives, soon to be easily out-competed by their more agile and intelligent human cousins. For all intents and purposes, Rosny’s descriptions of Neanderthals held just enough accepted details—just enough anthropological truth—about Neanderthals to make the story believable.

The key human attribute, for Rosny’s story, was the ability to create fire. Rosny’s sketch of Homo neanderthalensis showed a species capable of maintaining fire, but without mastery over it. Once the fire was lost, fire had to be discovered rather than created. Rosny describes humans as creating, caring, tending, and raising fire—and fire was a tool that Rosny’s audience would read as the success to humanity’s legacy. There was something metaphysical about human history that Rosny’s characters, and anthropomorphized fire, inspired.

Faouhm raised his arms to the sun with a long yell. “What will become of the Oulhamrs without Fire? How shall they live on the savanna and in the forest? Who will defend them against shadows and winter blasts? They will have to eat raw meat and bitter plants, never to warm their limbs, and their spearheads will remain soft. The lion, the saber-toothed tiger, the bear, the tiger, the giant hyena will eat them alive during the night. Who will recapture Fire?”

When Quest for Fire was turned into a film in 1981, the appeal of the story remained because it asked audiences to puzzle out the metaphysics of evolution and origins. Where did we come from? Where are we going? What does our past make us? These themes drove Quest for Fire in 1981 just as much as it did in 1911.

While it is easy to retire Ron Perlman’s Oscar-winning Pleistocene make-up (and that famous moth-eating scene) to Hollywood’s archives, the characterization of the Neanderthal species provided in the film still provides a space to explore the questions of what makes us human—a phylogenetic foil in the literal and literary senses. One hundred years post-Rosny’s Quest, the questions and the characters endure as the scientific community expands interpretations of material culture and archaeological remains but struggles with its own histories.

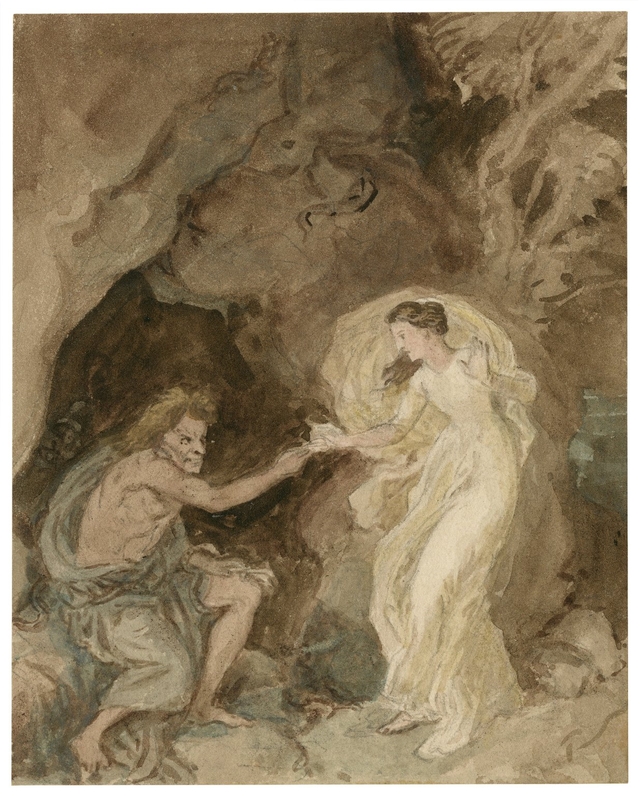

If you want to find the beginnings of a popular literary trope, starting with Shakespeare isn’t a bad bet. Writer and biologist Vladimir Nabokov argued The Tempest was an early precursor to the science fiction genre: Caliban and Ariel—the savage and the ethereal spirit—backstop many traditional elements of imagined histories and futures. Drawing on the themes of Montaigne’s essay “Of Cannibals,” The Tempest uses elements like fantasy, magic, and especially irony to explore what makes humans “human.”

The Tempest and the Sentinel

The tragicomedy was published in the First Folio three hundred years before paleoanthropologists excavated the fossilized bones of Neanderthals in southern France. As material objects, the Neanderthal fossils prompted challenges to scientific categories of species, but as the fossils passed into pop culture they slotted into these long-established Shakespearean archetypes. Caliban and Arial challenge definitions of “human” and “civilized”—notions very much at the heart of speculative anthropology over the last century. Four hundred years post-Tempest, Caliban’s caricature serves, for better or worse, as an archetype in re-imagining long-extinct fossil species.

Caliban and Arial from “rough drawings (small) for scenes from Shakespeare” by John Massey Wright (1777-1866) Folger Shakespeare Library

While Neanderthals were the first fossil species explored in science fiction, they were by no means the only species. In the post-La Chapelle decades of paleoanthropology, more and more fossil species of human ancestors entered humanity’s phylogenetic tree. By the 1930s, australopithecines like the Taung Child had joined Neanderthals and other species of Homo. These new species piqued popular interest, through print, art, and particularly through science fiction. Where early twentieth-century Neanderthals and Quest for Fire posed metaphysical questions about humanity, the mid-twentieth century saw fossil species get tangled up with questions of ethics. After two world wars, researchers pivoted toward trying to trace the history of human violence and morality. The evolutionary history of human morality—the hows and whys of human violence—percolated through both the science and the science fiction of the era.

By the late 1950s, the cast of human ancestors had expanded to include australopithecines—Australopithecus africanus—as well as Neanderthals. Australopithecines were accepted into the paleo community as human ancestors by the mid-twentieth century based on South African fossils like the Taung Child and Mrs. Ples. But even as questions of taxonomy were resolved, the question of how the species behaved—did it have a culture? what did that look like?—intrigued the scientific community, particularly paleoanthropologist and anatomist Dr. Raymond Dart, discoverer of the Taung Child fossil. For several decades, Dart examined a series of artifacts sites in northern South Africa, like Sterkfontein and Makapansgat. Based on his initial studies, in the 1940s, Dart was quick to note the high presence of what looked like purposefully shaped bone in addition to shaped stone tools.

Dart concluded that the fossilized bones and stone tools from the sites were created by Australopithecus africanus, and that these australopithecines were “predatory ape-men,” bludgeoning their way across the landscape. He called this complex of stone and bone technology the Osteodontokeratic Culture (Bone, Tooth, & Horn Culture or ODK) and argued that the artifacts were a collection of tools. In ODK culture, Taung and his ape-men were ruthless hunters—the dominators of the landscape and savages, really, with all of the charged connotations of the term.

Where Dart had imagined a blood-thirsty, bone-club-wielding, violent set of human ancestors, others in the scientific community (such as Dr. Wilford Le Gros Clark), argued that Dart’s ODK culture pushed the limits of scientific evidence and interpretation. Clark argued that Dart’s ODK depended primarily on a lack of alternative hypotheses for the scientific community to evaluate. (In other words, what would account for the accumulation of bones if not human ancestors?) What Dart’s hypothesis did, however, was usher in new fields of study within archaeology and paleoanthropology, like taphonomy, which looked at how soils and bones and rocks accumulated in caves like Makapansgat. New studies by researchers Dr. Sherwood Washborn and Dr. Charles Brain determined that natural causes accounted for the accumulation of bones in caves. Brain’s studies took the budding field of taphonomy one step farther away from ODK-like interpretations by matching leopard teeth to puncture marks in a recovered australopithecine skull from Swatkrans. These findings—like the tooth punctures—revealed that hominins were vulnerable to predation: the hunter was now interpreted as the hunted. While Dart’s theories never quite gained the heft or momentum he wanted in the field, the ODK culture convinced many to “prove it wrong.”

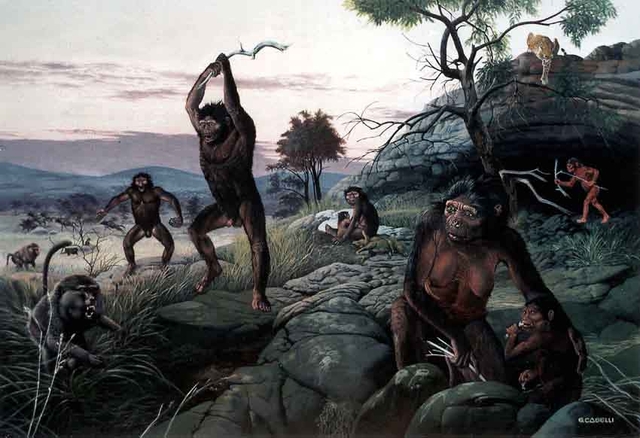

“Australopithecus at Home” by Giovanni Caselli. Courtesy of Giovanni Caselli

In public imaginations, however, the idea of a savage human ancestry caught fire, thanks in no small part to author, playwright, and trained anthropologist, Robert Ardey, and his popular African Genesis: A Personal Investigation into the Animal Origins and Nature of Man.

Reviews of African Genesis described the book as

Presenting a fascinating array of new scientific evidence, largely accumulated over the past thirty years of the origins of man. It is the author’s unorthodox and intriguing theory that Homo sapiens developed from carnivorous, predatory killer apes and that man’s age-old affinity for war and weapons is the natural result of this inherited animal instinct.

While not science fiction, per se, African Genesis was unquestioningly pivotal in disseminating the Killer Ape Hypothesis to those outside of conversations within academic anthropology. Ardey saw African Genesis filling a role that in contemporary literature might call narrative nonfiction.

Not in innocence, and not in Asia, was mankind born … In neither bankruptcy nor bastardy did we face our long beginnings. Man’s line is legitimate. Our ancestry is firmly rooted in the animal world, and to its subtle, antique ways our hearts are yet pledged. Children of all animal kind, we inherited many a social nicety as well as the predator’s way. But most significant of all our gifts, as things turned out, was the legacy bequeathed us by those killer apes, our immediate forebears. Even in the first long day of our beginnings we held in our hand the weapon, an instrument somewhat older than ourselves.

Elements of the ODK culture intrigued science fiction great Arthur C. Clarke, whose writing painted humanity’s past as violent and destructive. His short story “The Sentinel” (written in 1948, a year after Dart’s the discovery of ODK specimens) looked to deep time in order to explain humanity’s present and “savage” condition. The story focuses on an usual artifact, found on Earth’s moon, that seemed to be sending signals out into the universe. As the story unfolds, we learn that the transmitting artifact was encountered by humans and then left on the Moon as a mysterious material legacy, much like the way scientists uncovering tools from the archaeological record work to understand a material culture long past. “The Sentinel” emphasized the power and pervasiveness of tools and technology and the role that these play in shaping human history. Clarke’s story gave his audiences the literary distance to read this transmitting artifact as a parallel to other technological innovations in human history—or not. “The Sentinel” would go on to inspire Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Clarke’s artifact became the monolith in 2001, surrounded by furry human ancestors wielding weapons much like the ODK culture. Like Rosny’s details in Quest for Fire, the anthropology Clarke (and later Kubrick) included in their science fiction made their stories just believable enough to attract their audience’s interest.

The interpretation of the australopithecines, much like the Neanderthals decades earlier, became imbued with meaning and morality. These themes became deeply entrenched in the public’s mind and long associated with fossils like Taung. However, much science points to a hominin that was very much at the mercy of its environment.

ODK culture was eventually shown to be fossilized horn cores from extinct antelope, the result of the natural, taphonomic processes of fossil formation. The presence of the cores at Makapansgat were not the result of hominin actions, a discovery that completely undercut Dart’s hypotheses. Yet while Dart saw his Killer Ape and ODK culture fall out of favor, he never really lost his sense that humanity’s history was long and dark.

Hominins, Humans and Hybrids

Rosny’s Quest for Fire looked to La Chapelle’s Neanderthal bones and Clarke’s speculative anthropology looked to material culture as inspiration for their science fiction worlds. Today, with the recent publication of the Neanderthal genome, it would appear that interest in mapping new anthropological discoveries onto the literary tropes of science fiction is just beginning.

By the end of the twentieth century, Neanderthals had come back in vogue for science fiction and speculative anthropology. Canadian sci-fi writer Robert Sawyer drew heavily on the then-most up to date paleoanthropology for the Neanderthal Parallax trilogy Hominins, Humans, and Hybrids, published in 2003-2004. Sawyer’s details—like those of Rosny—were well-researched and rang just true enough to lend anthropological legitimacy to the stories.

In the trilogy, Sawyer lays out two different Earths—an Earth, as we traditionally consider it, and an Earth where Neanderthals became the dominant hominin 250,000 year prior. In this parallel world humans (or gliksin) went extinct, not Neanderthals. (Sawyer’s Neanderthals posit that the extinction of gliksin was due to technological superiority of Neanderthals, an inability to adapt to climate conditions, and a general inferiority of intelligence.) These two Earths cross when the Neanderthal physicist Ponter Boddit manages to travel between the Neanderthal world and our own Earth, through a portal that opens up at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory’s physical lab.

The Neanderthal Parallax trilogy asks: What if Homo sapiens came from a dark and violent evolutionary history? How would that shape and explain how we make sense of culture today? What if Neanderthals “won” the Pleistocene and outcompeted modern humans? How would those hominins read human evolutionary history?

The winner of a Hugo Award, Hominins examines those what-if scenarios through Neanderthal and human interspecies relationships. Sawyer’s attention to detail and his paleoanthropological research provide the same gestures toward scientific legitimacy as Rosny’s survey of La Chapelle and the ODK literature. The paleoanthropological research Sawyer does—and the experts he interviews—is meticulous and thorough. The Neanderthal Parallax trilogy centers around the question of how to define humanity. By anatomy? By society? By history? Agency? By juxtaposing the Earth that’s familiar to readers with an Earth where humans, rather than Neanderthals, become extinct during the Pleistocene, Sawyer generates a plot to explore these themes. In Sawyer’s trilogy, Neanderthals live in a world where crime is unheard of and culture is completely cooperative. By “humanizing” Neanderthals in such a way, Sawyer’s trilogy draws on more recent decades of Neanderthal research; research that demonstrates Neanderthal culture was complex and more nuanced than people like Henry Fairfield Osborn had originally argued.

For anthropology, science fiction dramatizes an imagined past; it offers these “what ifs?” as explanations for why modern society is the way it is. The “what if” question takes the discovery of a fossil and introduces that discovery to audiences outside of a strictly scientific community. For Rosny, the invention of fire set humans on a path toward technological mastery. Science fiction inspired by Dart’s ODK culture and the violence of 2001, by contrast, spoke to a dark and bloody evolutionary history. More recent sci-fi interpretations of the human past like the Neanderthal Parallax series interrogate the boundaries between human and not-quite-human.

These questions will remain salient in the twenty-first century and beyond. And though we usually associate science fiction with the future, it also explores imagined pasts—the trajectories that brought us here, and which will shape where we’re going. Thinking about, researching, and dramatizing our long-extinct human ancestors provides intellectual space for a metaphysics of past and future humanities that extends beyond the material record.

The author would like to thank CJ Heim and Charles Heim for their questions and discussions about Neanderthals and science fiction—this prompted a much-needed rereading of Quest for Fire. The author would also like to thank the Institute for Historical Studies, University of Texas at Austin.