“The Lying Pen of the Scribes”: A Nineteenth-Century Dead Sea Scroll

The original version of Deuteronomy.

That’s how the newly-discovered text was billed in August 1883. Several fragments of a 2,800-year-old scroll had made their way into the hands of Moses Shapira, an antiquities dealer in Jerusalem. According to Shapira, a group of Arabs

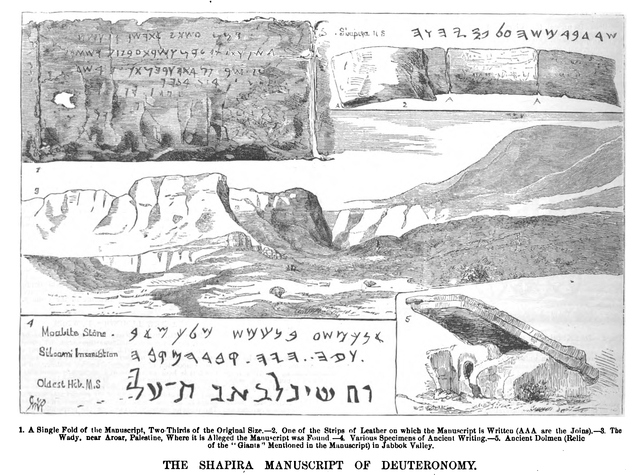

had hidden themselves, in the time when the Wali of Damascus was fighting the Arabs, in caves hewn high up in a rock about an hour east of Aroar, near the Modjib. They found there several bundles of old black linen. They peeled away the linen, and, behold, instead of gold, which they expected to find, there were only some black inscribed strips of leather (called Nekesh, which means some signs or scratches), which they threw away (or I believe he said threw into the fire, but I am not certain); but one of them picked them up and kept them in great honour as charms, and he became a rich man, worth three hundred sheep.

Now Shapira offered the scroll to the British Museum provided they pay one million British pounds. It was an enormous sum at the time—but a small price to pay if the text was authentic.

To find out, the British Museum enlisted the services of an expert Hebraist, Christian David Ginsburg. But in Shapira’s eyes these tests of authenticity were mere formalities: he seemed convinced of its antiquity. In the meantime, the Museum put two of the fragments on display. Soon crowds were thronging to see it, including Prime Minister Gladstone himself. The original Deuteronomy was a sensation.

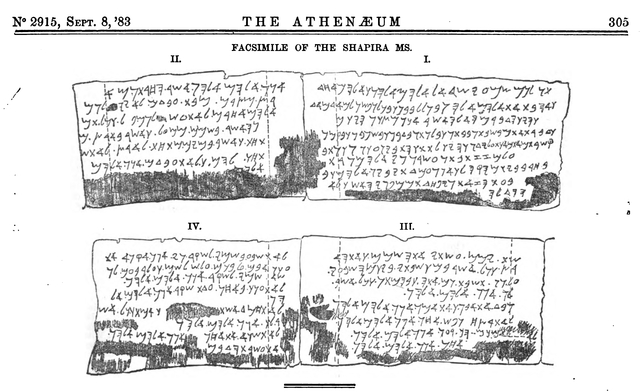

Ginsburg’s facsimile of 4 columns of the Shapira Strips, including the Ten Commandments. The Athenaeum, September 8, 1883, p. 305.

Another face in the crowd was Charles Clermont-Ganneau: archaeologist, biblical scholar, explorer of Palestine. He had been on Shapira’s trail for over a decade. Ten years earlier, Shapira had sold a set of roughly 1700 figurines and pottery vessels to the Old Museum in Berlin as remains of the ancient Moabite civilization. Clermont-Ganneau played a crucial role in revealing the “Moabitica” to be forgeries, their script copying the recently discovered Mesha Stele, aka the Moabite Stone, which Clermont-Ganneau himself had been instrumental in publicizing and preserving. (Whether Shapira had any role in the fiasco beyond selling the artifacts was, and remains, unclear.) Now Clermont-Ganneau was closely scrutinizing Shapira’s newest discovery. Not surprisingly, Shapira refused him access to the scroll. Ginsburg let him briefly inspect a couple of the strips, but for the most part Clermont-Ganneau was forced to catch glimpses through the crowds like any other member of the public. Despite these difficulties, Clermont-Ganneau rapidly reached his conclusion: the manuscript was a forgery.

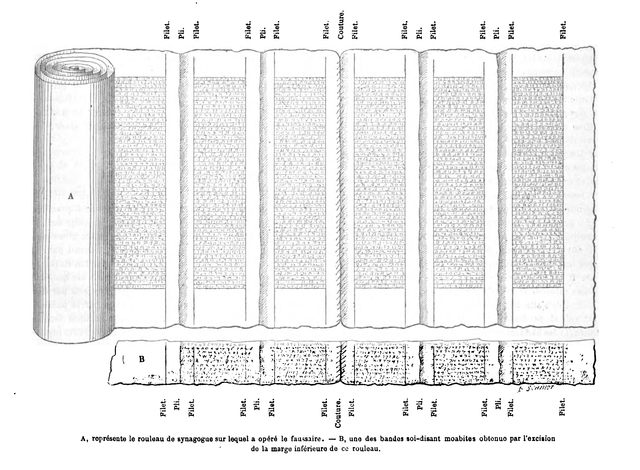

What’s more, he implicated Shapira himself in the forgery. Clermont-Ganneau noted that Shapira had previously sold the British Museum a series of medieval Torah scrolls he had acquired in Yemen. According to Clermont-Ganneau, Shapira had formed the Deuteronomy strips by simply cutting the bottom margins of some medieval scrolls, then applying chemicals to the surface to give them the appearance of antiquity.

Clermont-Ganneau’s diagram of how he believed Shapira had made his strips. Revue politique et littéraire: revue bleue 3rd series, no. 13 (September 29, 1883): 389.

The public rejections of the scholarly community followed en masse. Adolphe Neubauer, rabbinic Hebrew scholar at Oxford, and Archibald Sayce, eminent Assyriologist and tutor at Oxford, had already had letters published in The Academy proclaiming the manuscript a forgery. Claude Conder, co-director of the Survey of Western Palestine, also published a letter in the Times denouncing the fraud. Then came the verdict for which everyone had been waiting: Ginsburg wrapped up his three-week analysis and declared the manuscript a forgery. Ginsburg, who was perhaps deliberately drawing out the process in order to build suspense and interest. Ginsburg, who in the past had approved of Shapira’s sale of medieval Hebrew manuscripts to the Museum.” On top of all of this, it soon came out that, before he arrived in London, Shapira had brought his strips to Germany, offering them for sale to the Royal Library in Berlin but meeting rejection from a series of distinguished scholars.

More than simply rejection, this was a public humiliation. Apparently it was too much for Shapira. He continued to argue for the genuineness of the manuscript, or at any rate for his innocence—even suggesting that if forged it must have been the work Clermont-Ganneau himself, in an effort to frame him. But Shapira quickly fled England for Amsterdam, then Rotterdam where he checked into a hotel, and, on March 9, 1884, shot himself.

As for the manuscript itself: Shapira had left it with the British Museum when he fled England in haste. It was bought by the bookseller Bernard Quaritch in a Sotheby’s auction in 1885. Quaritch himself offered them for sale two years later, for a sum of £25. The manuscript that had once been valued at a million. It was subsequently lost: Alan Crown’s research suggests that it was likely acquired by Sir Charles Nicholson, an important figure in the founding of the University of Sydney, and likely burnt in a fire in Nicholson’s study in England in 1899.

And so ended the story of the ill-fated Shapira Deuteronomy.

There’s a good reason why the story of Shapira’s scrolls might sound familiar, despite its obscurity. The tale of their discovery is remarkably similar to that of a far more famous find related to the Bible. Six decades later, in the winter of 1946-47, an Arab shepherd named Muhammed edh-Dhib followed a stray goat into a cave at Qumran, near the Dead Sea. There he and two friends discovered seven fragile scrolls of animal hide, wrapped in linen and stuffed into an ancient jar. These were the first of the Dead Sea Scrolls: a series of texts including the oldest manuscripts of most of the books that would eventually make up the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament, as well as many other lost writings. It was a discovery that would capture the world’s attention, ignite considerable controversy, and revolutionize our knowledge of ancient Judaism and Christian origins.

Looking back today, the similarities between the two narratives of biblical finds at the Dead Sea must give us pause. Many of the original objections to the Shapira scrolls now seem obsolete, even humorous. For instance, several eminent scholars were convinced that no sheepskins could survive for thousands of years in Palestine. Archibald Sayce dismissed the find in this way:

It is really demanding too much of Western credulity to ask us to believe that in a damp climate like that of Palestine any sheepskins could have lasted for nearly 3,000 years, either above ground or under ground, even though they may have been abundantly salted with asphalt from the Vale of Siddim itself.

Meanwhile, in the publication of his results in the Times, Ginsburg listed a series of criteria by which he could conclude that the strips were forged: external criteria (relating to the format of the strips themselves, and echoing Clermont-Ganneau’s arguments), and internal criteria (relating to the script, the language, and the text). These include the short height of the strips (only 8-9 cm), the vertical lines serving as margins for each columns (but with text extending beyond them), the use of dots as word dividers.

Yet these feature, as identified by Ginsburg and others, are matched on at least some of the actual Dead Sea Scrolls. While Shapira’s manuscript may not work as a ninth or eighth or seventh-century text, in several respects it does resemble texts from the last two centuries BCE. By that time, the old Hebrew script of the Iron Age—what Shapira’s manuscript is written in—had been replaced in most writing by the square Jewish script adapted from Aramaic writing. However, there was a revival of the old script, referred to as paleo-Hebrew, in some special cases. These include coins of the second century B.C.E. through the second century CE—and a few of the Dead Sea Scrolls, especially books of the Pentateuch (like Deuteronomy), presumably because they were seen as most ancient. This would also account for some of the late (post-biblical) forms and vocabulary identified by Neubauer and the German biblicist Hermann Guthe.

A second century C.E. coin from the Bar Kokhba revolt with Paleo-Hebrew script. The left inscription reads “For the freedom of Jerusalem” and the right reads “Year two of the freedom of Israel.”

Not only that, but as has been widely observed, the discoveries of the 1940s and 1950s were not the first time that scrolls were found in the vicinity of the Dead Sea. In the last few decades, scholars have traced a long history of reports of scroll discoveries in the region. As early as the third century C.E., the church father Origen described manuscripts found in his time in a jar (or jars) near Jericho; the report was repeated by Eusebius, Athanasius, and Epiphanius in the following centuries. Around 800 C.E., Timotheus, bishop of the Eastern Orthodox church in Baghdad, wrote about a similar discovery of non-canonical scrolls; the story he told is again eerily similar, of an Arab hunter who followed his dog into a cave. Meanwhile, in the tenth century, Yaʽqūb al-Qirqisānī, a Karaite scholar (Karaism being a breakaway Jewish movement, originating in the Middle Ages, which did not recognize the authority of the Talmud), discussed an ancient group of people known as al-Maghāriyah (the “cave people”) because they left books in caves.

In light of these sorts of considerations, several scholars lobbied for the case of Shapira’s Deuteronomy to be reopened. These included Menahem Mansoor, professor of Hebrew at the University of Wisconsin; and the eccentric Dead Sea Scrolls publication team member John Marco Allegro, perhaps best known for his book The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross. In fact, the parallels occurred to more than simply those who wanted to reevaluate the Shapira case. The most prominent critic of the Dead Sea Scrolls’ authenticity upon their initial discovery, Solomon Zeitlin of Dropsie College, dismissed them as either medieval texts or modern forgeries—arguing in part because of their similarity to the Shapira strips!

Reproductions of the manuscript and the location where it was found in an 1883 issue of Scientific American. Scientific American, October 27, 1883

So should we reconsider the authenticity of Shapira’s nineteenth-century Dead Sea scroll?

In my opinion, we must still conclude that Shapira’s scroll was a forgery. Beyond any external or internal criteria, consider this simple fact: we are dealing with a manuscript that can only be traced back to an antiquities dealer, whose story about their discovery has never been verified—a dealer, moreover, who had previously been involved in the sale of forged artifacts. Especially since the strips themselves are lost, we must adopt the position that they are a fraud as our default. Beyond this, of course, some of the objections raised by Ginsburg and others are most certainly legitimate: certain lexical items, forms, and spellings are bizarre in any period. There are also various aspects of Ginsburg’s facsimile, such as the form of the letters themselves: they are typical of monumental inscriptions in stone, not of paleo-Hebrew manuscripts written in ink.

The text, in short, is almost certainly a fake.

In the nineteenth, twentieth, and even twenty-first centuries, the Shapira manuscript has provoked a particularly hostile reaction: invective, hyperbole, ridicule, and more, directed both at the manuscript and at Shapira himself.

William F. Albright opined shortly after the announcement of the Dead Sea Scrolls:

Since several scholars have compared the new Scrolls to the so-called archetype of Deuteronomy, offered by the notorious forger Shapira to the British Government for a million pounds, it should be emphasized that there is nothing whatever in common between them except the fact that texts of the Hebrew Bible written in ancient scripts are involved [emphasis in original].

A similar dismissive tone, but even more hostile, can be found in the responses of scholars like Moshe Goshen-Gottstein and Oskar Rabinowicz. The articles of Goshen-Gottstein and Rabinowicz include quite personal attacks against those asking for a reevaluation of the evidence, specifically Mansoor and Allegro—attacks based on no more than a cursory presentation of the evidence.

More recently, consider the discussions by Kyle McCarter and André Lemaire in the more popular magazine Biblical Archaeology Review. Lemaire welcomed the opportunity to revisit the episode, but then simply affirmed the objections of Ginsburg and Clermont-Ganneau—even though many of these apply just as much to the Dead Sea Scrolls. Most remarkably, he asserts (and repeats in a letter to the editor in Biblical Archaeology Review in response to Mansoor) that het/kaf and tet/tav confusions do not occur in ancient texts. This is simply wrong: both confusions are attested multiple times in texts from Qumran.

Meanwhile, McCarter claimed that interest at the time in Britain, in the Shapira manuscript and in the Bible and religion more generally, was due largely to the work of biblical critic Julius Wellhausen (the second edition of his seminal Prolegomena, and the first edition under that title, was published in German that same year). While some British accounts of the affair (by both scholars and journalists) refer to the work of biblical critics generally, many do not, and biblical criticism is never a major focus of the responses; Wellhausen and his work are never named; and the second edition was not translated into English until 1885. And in Germany there was no similar reaction when Shapira brought his strips. Even in Guthe’s book on the Shapira manuscript, published in Germany in 1883, Wellhausen’s name is limited to three footnotes on minor points, and none is to the Prolegomena. Certainly, we would do better to contextualize the public excitement in England in the religious climate of the day, and natural interest in an ancient (and possibly “original”) manuscript of Deuteronomy.

I do not mean to call into question the integrity of these biblical scholars and archaeologists and epigraphers. My point is a different one: even prominent, important scholars have been quick to dismiss the Shapira strips, often with sloppiness and hostility. Even those expressing interest in a reevaluation have done so without proper analysis or context. Most, however, have been swift to reject them, often without careful consideration—and in fact to condemn or ridicule both the scroll and Shapira personally, in decidedly non-scholarly language.

The same is true, as we have seen, for the original response to the strips. Personal attacks are widespread in the public letters of Clermont-Ganneau, Neubauer, and others. Neubauer, like Goshen-Gottstein later, explicitly rejected the need to waste much time with a comprehensive review. In particular, consider the comment of Sayce quoted above. Or Clermont-Ganneau, in his first letter to the Times:

Let there be given me a synagogue roll, two or three centuries old, with permission to cut it up. I engage to procure from it strips in every respect similar to the Moabitish strips, and to transcribe upon them in archaic characters the text of Leviticus, for example, or of Numbers. This would make a fitting sequel to the Deuteronomy of Mr. Shapira, but would have the slight advantage over it of not costing quite a million sterling.

As the London newspaper The Echo put it at the time, “From the moment that the discoveries were declared to the world there was an eagerness in many quarters, quite inconsistent with the true spirit of criticism or scholarship, to stigmatize them as forgeries.”

What is the reason for this reception? What accounts for such an unfavorable ratio of scholarly care to overheated rhetoric?

I think we can offer a series of answers for the particularly hostile response to Shapira’s exhibition of the scrolls in 1883. One, of course, is that Shapira had already been revealed once as a seller of forged objects. In particular this may have animated Clermont-Ganneau, and it may have led to a personal vendetta on his part against Shapira. (It is worth noting that there may also have been tension between Ginsburg and Clermont-Ganneau, as Ginsburg had previously implicated Clermont-Ganneau’s actions in inadvertently contributing to the dismantling of the Mesha Stele.) But this is not enough. After all, the revelation of the Moabitica forgery did not stop Ginsburg’s approval of the medieval scrolls Shapira sold to the British Museum. Nor did it affect the opinion of other scholars concerning these manuscripts: In a letter published in the June 11, 1881 edition of The Academy, Sayce praised a collection of such manuscripts Shapira was bringing to London, concluding: “It would be a pity if the collection were allowed to go to Berlin like its predecessor.”

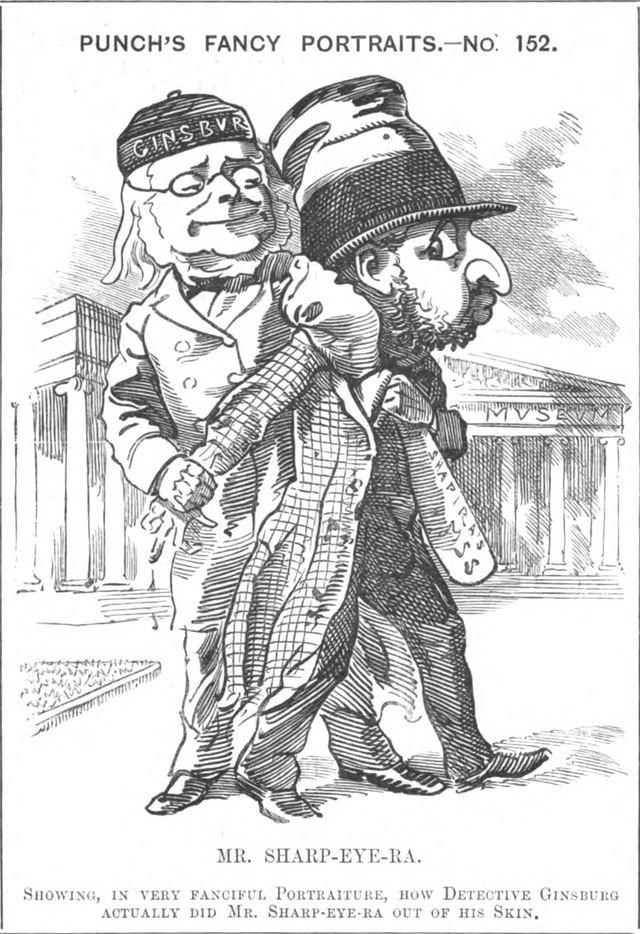

Another answer is racism. Several responses to the Shapira affair highlights Shapira’s Jewish heritage (he was born Jewish but had converted to Anglicanism). Walter Besant, secretary of the Palestine Exploration Fund, recalled Shapira this way in his autobiography: “a Polish Jew converted to Christianity but not to good works.” Of particular interest is a cartoon appearing in the British humor magazine Punch in September 1883.

The cartoon depicts Ginsburg apprehending Shapira, with the latter caricatured in a stereotypically anti-Jewish manner, particularly with a large nose. Of course, not only was Shapira a Jewish Christian convert, but so was Ginsburg—who is not negatively stereotyped in any way. In fact, this differential treatment of the two converted Jews is typical of the British press, which (as Fred Reiner has discussed) lionized Ginsburg as protector of England from the scheming Shapira. (In this narrative, the earlier critiques of Neubauer and especially of the Frenchman Clermont-Ganneau are forgotten—a fact that Clermont-Ganneau complained about at length in his Les fraudes archéologiques.)

It may be that Shapira was targeted specifically as an eastern Jew: born in Russia and, even worse, living in Jerusalem. Thus W.J. Loftie wrote at the time in the literary magazine The Manhattan: “It seems strange, however, and not easy to believe, that anyone living at present in the semi-barbarous Levant can write in the letters of the ancient Phoenicians with such ease and accuracy as to deceive.” (Actually, Loftie scored a two-fer: just before this he had criticized Clermont-Ganneau for his “truly French self-complacence.”) Compare a quote from a later review of the affair by John A. Maynard:

In these Eastern lands, blessed with intense sunshine, there is no such thing as a cold fact. The sheen of romance which has escaped so many of our scholarly Bible critics makes fiction very real to its creators. There the liars come very soon to believing their own lies.”

But all of these reactions to Shapira postdate the rejection of his manuscript. In that light, they may be better seen as a symptom of the rejection and not as a (major) cause.

On the other hand, what if we look at the Shapira scroll and its reception in the context of other scroll discoveries, or claims of scroll discoveries, and their reception? The ancient reports generally do not even hint at suspicion of genuineness: Origen, Eusebius, Athanasius, Epiphanius, Timotheus, al-Qirqisānī, all accept the reports at face value.

What accounts for the difference? The answer seems simple enough: the rise of modern critical scholarship. The development of linguistic competence in both language and script, and the ability to provide proper historical context, have revolutionized how we understand ancient texts, and how we understand the ancient world itself.

In “Why All the Fuss?” McCarter suggests that one reaction of the public to the Shapira manuscript would have been to question the validity of critical biblical scholarship. And to a limited extent we do see this reflected in newspaper article at the time; it is also echoed in the “scoffing atheists” in the Quaritch listing. But we must not forget that biblical scholarship itself is not an objective critical enterprise. It, too, is deeply rooted and intertwined with religious views. The Shapira manuscript, a purported original or ancient version of Deuteronomy with many divergences from the canonical version, could have been seen as a threat both to critical scholarship and its religious foundations. And in fact this view appears explicitly in the comments of Konstantin Schlottmann, Protestant theologian and scholar, who had responded to Shapira about the manuscript when Shapira claimed to have first received it, back in 1878: “How dare I to call this forgery the Old Testament? Could I suppose even for a moment that it is older than our unquestionable genuine Ten Commandments?”

We see the potential, realized with Schlottmann, for even scholarly response to be entangled with religious belief. This should not be surprising: modern biblical scholarship has been overwhelmingly Protestant, both in its origins and in its practitioners. Its roots are found in the two towering movements of the Renaissance and the Reformation, with their mottos ad fontes (“to the sources”—not only classical antiquity but also biblical antiquity) and sola scriptura (“by scripture alone”). The Protestant background of biblical scholarship has been long acknowledged. But this is mostly a neutral observation, or a positive praise of its critical tools; it has rarely been acknowledged that this origin might have a negative side.

The development of historical context and perspective, from the perspective of “to the sources” and “by scripture alone,” has led to a near obsession with origins, and specifically with origins of Scripture. Discovering the original documents behind the Pentateuch, establishing the (single) original form of the biblical text, reconstructing the (single) source (Vorlage) of a biblical translation—these have been among the most important goals of modern scholarship. Perhaps this may explain how, when the Dead Sea Scrolls were first brought to the attention of scholars, before archaeological excavations at Qumran confirmed their authenticity, they were generally accepted by scholars: unlike the Shapira scroll, they did not claim to be original versions of biblical books but part of a later stage in the process of transmission. Consider the reaction of biblical scholar Harry Orlinsky to the Dead Sea Scrolls: he believed them to be of limited importance for biblical studies, because they had little bearing on the original form of the biblical text.

If we reconsider John Maynard’s statement above, we realize it may be quite helpful for understanding ancient modes of thinking. The focus on “cold facts,” on origins and linear evolution, on our Bible, can mislead us when we turn to the variety of sacred writing and the variety of textual forms for individual books throughout so much of antiquity. In other traditions, at other times, scripture did not necessarily equal Scripture. It is an illuminating way to consider things like pseudepigrapha, instead of as “pious frauds”—and of course the original “pious fraud” of the Bible, the book of Deuteronomy itself. It is perhaps the ultimate irony that the Shapira strips pretended to be the original version of a book that scholars think in some sense was “fake”: scholarly consensus holds that Deuteronomy is the ancient book of the law referred to in 2 Kings 22, claimed to be miraculously “found” in the reign of Josiah king of Judah, but in fact written at that time.

While on the one hand modern biblical scholars stand apart from earlier readers of the texts in their historical and philological concerns, on the other hand we too have been thoroughly influenced by our environments—personal, cultural, or religious. We cannot simply draw a bright line between ancient and modern interpreters. Broadly speaking, our understandings are not purely “objective”: they are formed from a range of influences and agendas, as the Shapira incident demonstrates clearly.

In biblical scholarship in particular, those understandings, like the understandings of ancient readers, cannot be divorced from considerations of religion—especially when considerations of religion are intimately integrated into the very methods we as scholars use. I am by no means dismissing the importance of historical and philological approaches, or of the advances made by modern scholarship in understanding the ancient world. But those advances are ultimately limited by our distance from that world, and by the fragmentary state of its remains. The result is that the remaining pieces are filled in to some extent by our own imaginations.

Paradoxically, the study of the past always keeps one eye on the future. Historical research is important not simply for its own sake, but for what we can learn from it and apply to the future. More than that, our understandings of the past are always in flux, changing with the discovery of new data, and changing as we ourselves change and adopt new paradigms. In order to understand the past better, we need to accept a simple truth about ourselves: we are merely the latest in a long line of interpreters of texts—another chapter in the reception of antiquity.