Back to the Neotechnic Future: An Online Chat With the Ghost of Lewis Mumford

Conducted by Aaron Sachs, Cornell University, April 2014.

Mumford, the great urban theorist, architecture critic, and cultural historian, has been dead for almost a quarter century. But I’ve been spending so much time with his work over the last couple of years that I sometimes have hallucinations in which he speaks to me in sentences from his books. (That’s normal for scholars, right?) He was so broad-minded that his words seem germane to numerous situations. Indeed, the relevance of his thinking to the 21st century has reinforced my suspicion that we have not entered a completely new “postmodern” era but are merely experiencing an intensification or radicalization of certain modern trends—trends that Mumford analyzed back in the 1920s and 30s with a bracing freshness. And yet, some developments—the Internet, most importantly—do seem utterly novel. What would Mumford have made of cyberspace?

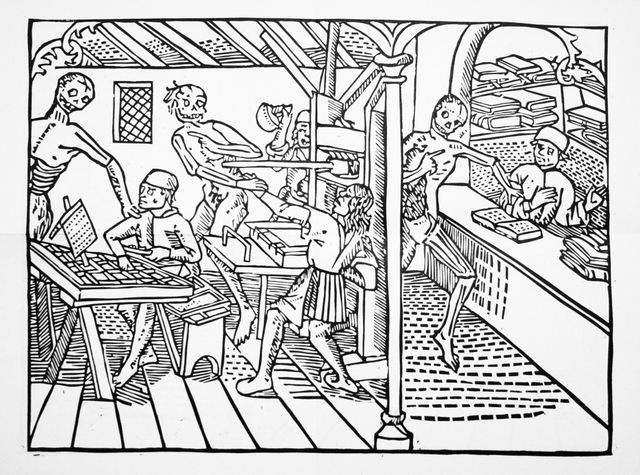

At least one fan of his work thinks it’s pretty obvious. In the 2010 re-issue of Mumford’s Technics and Civilization, put out by the University of Chicago Press, a publisher’s note warns that the Press chose not to include Mumford’s 15 pages of illustrations, explaining that “it is not practical to reproduce those images here—nor is it necessary, in an age when readers can find the same, or similar, images on the Internet (an invention Mumford would have loved).”

But would Mumford have loved the Internet? Technics and Civilization itself features some intriguing answers. The text turns eighty this year, and the voice behind it sounds a bit grumpy, but still quite… what’s the word? Animated?

Mumford was perhaps the most prominent public intellectual of the first half of the twentieth century. He’s made a comeback recently among environmental scholars, thanks largely to his elaboration of a kind of bioregionalism. And he could surely be useful to those who analyze cities and technology. In Technics, he famously divided modern human history into three key periods: the promising eotechnic age, characterized by humble institutions like grist mills and by a general sense of sufficiency; the devastating paleotechnic age, when industrialism took hold and mining the earth became a defining human activity; and the gradually dawning neotechnic age, the era of distributed energy, lighter materials, and environmental balance. Well, two out of three neotechnic attributes ain’t bad, right?

I found Mumford’s ghost in the Bleeping Computer chat room.

Aaron Sachs Mr. Mumford, welcome to the new neotechnic!

Lewis Mumford To the extent that neotechnic industry has failed to transform the coal-and-iron complex, to the extent that it has failed to secure an adequate foundation for its humaner technology in the community as a whole, to the extent that it has lent its heightened powers to the miner, the financier, the militarist, the possibilities of disruption and chaos have increased.

Aaron Sachs But surely, Mr. Mumford, you acknowledge the democratic promise of the Internet? Surely you find technologies like email to be more connective than disruptive? Paperless offices, instant communication, social media buttressing cultures of protest, electric cars, biotechnical design; it’s as if the budding technologies you identified 80 years ago have finally come into full bloom.

Lewis Mumford The gains in technics are never registered automatically in society: they require equally adroit inventions and adaptations in politics; and the careless habit of attributing to mechanical improvements a direct role as instruments of culture and civilization puts a demand upon the machine to which it cannot respond.

Aaron Sachs Of course—I couldn’t agree more: no one is pushing technological determinism here. But I’m surprised by your gloomy tone. One of the reasons your work has endured is that you were always constructive, avoiding the relentless negativity of strict antimodernism and anticapitalism. Didn’t you see the rise of the neotechnic, even in the ‘30s, during the Depression, as offering hope, as renewing an older tradition of recognizing limits and working within them?

Lewis Mumford Indeed, instead of simplifying the organic, to make it intelligibly mechanical, as was necessary for the great neotechnic and paleotechnic inventions, we have begun to complicate the mechanical, in order to make it more organic: therefore more effective, more harmonious with our living environment…. Once the organic image takes the place of the mechanical one, one may confidently predict a slowing down of the tempo of research, the tempo of mechanical investigation, and the tempo of social change, since a coherent and integrated advance must take place more slowly than a one-sided unrelated advance.

Aaron Sachs Yes! I figured you would be a fan of the slowness movement. I can picture you at your homestead in upstate New York, going for long walks, picking fruit from your orchard and vegetables from your garden, and engaging with the wider world by exploring the Internet. Isn’t it amazing how easy it is for people to contribute to our culture now? There are so many creative thinkers out there, not just living simpler, more conscientious lives but also blogging about it, sharing information, helping to shape a slower, more gentle society.

Lewis Mumford What we need, then, is the realization that the creative life, in all its manifestations, is necessarily a social product…. The essential task of all sound economic activity is to produce a state in which creation will be a common fact in all experience: in which no group will be denied, by reason of toil or deficient education, their share in the cultural life of the community.

Aaron Sachs OK, now we’re getting somewhere. Down with the digital divide! You were right, of course, to point out that we still have a dirty, volatile, unjust energy system, but computers are so efficient now, and such powerful tools, that plugging them into the global network clearly represents a social good. It’s the Internet, as Bill McKibben argues, that will allow communities to cut back and ease off without getting bored or reverting to a narrow traditionalism. That’s the balance we need—between acknowledging limits and thinking expansively—if we want to come together and solve new technical challenges like global climate change.

Lewis Mumford But these mechanical aids to efficiency and cooperation and intelligence have been mercilessly exploited, through commercial and political pressure…. We have multiplied the mechanical demands without multiplying in any degree our human capacities for registering and reacting intelligently to them. With the successive demands of the outside world so frequent and so imperative, without any respect to their real importance, the inner world becomes progressively meager and formless; instead of active selection there is passive absorption ending in the state happily described by Victor Branford as “addled subjectivity.”

Aaron Sachs Look, I know you’ve always had a pretty strong contrarian streak, but I’m trying to find some common ground here. Wouldn’t you acknowledge that your frame of reference is a bit out of date? Nothing in the 1930s even hinted at the sophistication and power of the Internet. The world may have been shrinking by then, but now it’s literally at your fingertips; every time you log on, it’s as if you’re connecting yourself to a solidarity machine. I’d argue that subjectivity has actually been bolstered by electronic networking.

Lewis Mumford One further effect of our closer time co-ordination and our instantaneous communication must be noted here: broken time and broken attention. The difficulties of transport and communication before 1850 automatically acted as a selective screen, which permitted no more stimuli to reach a person than he could handle…. Nowadays this screen has vanished…. It becomes more and more difficult to absorb and cope with any one part of the environment, to say nothing of dealing with it as a whole.

Aaron Sachs Well, speaking of screens: maybe this conversation would go better if we could see each other? Do you ever use Skype, Mr. Mumford? Or FaceTime?

Lewis Mumford When the radio telephone is supplemented by television, communication will differ from direct intercourse only to the extent that immediate physical contact will be impossible; the hand of sympathy will not actually grasp the recipient’s hand, nor the raised fist fall upon the provoking head.

Aaron Sachs You know, Mr. Mumford, tone can be really hard to read in this medium. I’m not sure what you meant by that last comment, but I feel pretty strongly that I’d like to hear your voice. Do you have a phone up there? Can I call you?

Lewis Mumford One is faced here with a magnified form of a danger common to all inventions: a tendency to use them whether or not the occasion demands.

Aaron Sachs I apologize. Can we just—

Lewis Mumford What will be the outcome? Obviously, a widened range of intercourse: more numerous contacts: more numerous demands on attention and time.

Aaron Sachs OK, I get it. We’re all busy. But now you’re starting to sound like a knee-jerk neo-luddite. Or a broken record. Or maybe a cranky robot. Come on: give this a chance. You’re not being true to your own worldview.

Lewis Mumford Communication between human beings begins with the immediate physiological expressions of personal contact, from the howlings and cooings and head-turnings of the infant to the more abstract gestures and signs and sounds out of which language, in its fullness, develops. With hieroglyphics, painting, drawing, the written alphabet, there grew up during the historic period a series of abstract forms of expression which deepened and made more reflective and pregnant the intercourse of men. The lapse of time between expression and reception had something of the effect that the arrest of action produced in making thought itself possible.

Aaron Sachs Hey, Mr. Mumford, thanks for the lecture. Right. All of us young instant messengers are basically thoughtless…. But let me try one last angle. Don’t you yourself say, in Technics and Civilization, that neotechnic developments are leading us “toward a dynamic equilibrium” and a more resilient culture, that in fact “wherever neotechnic instruments exist and a common language is used there are now the elements of almost as close a political unity as that which once was possible in the tiniest cities of Attica”?

Lewis Mumford Lewis Mumford is no longer in this chat room. He clicked an interesting-looking link and is now answering a questionnaire that promises to determine what career path he would have followed had he lived in the Middle Ages.

Aaron Sachs Seriously?

Lewis Mumford LOL!