The Case for Female Astronauts: Reproducing Americans in the Final Frontier

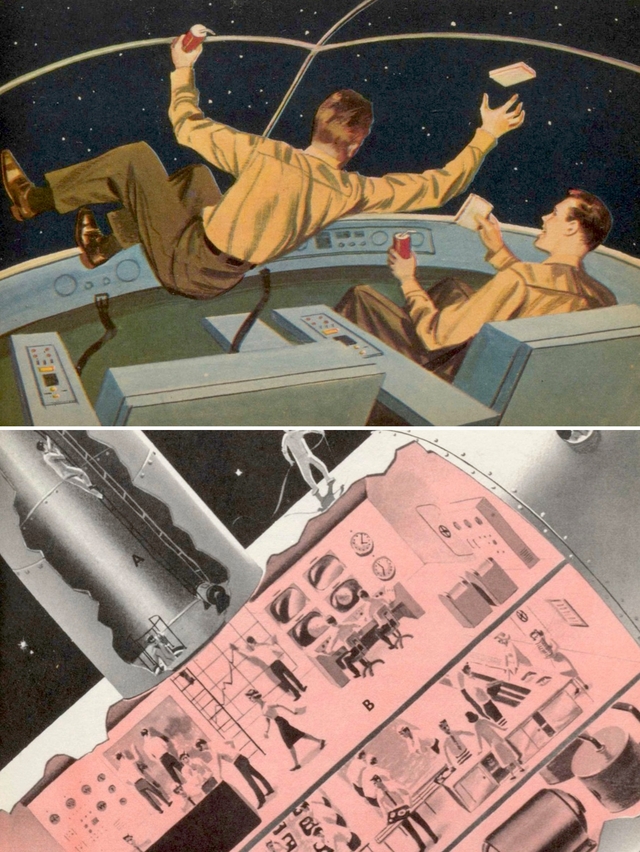

Children’s books envisioned what many could not: marriage and childbirth as a space colonist. Cox, Stations in Space, 1960

It’s bedtime in middle-class, white America, October 1962. Little Billy and Little Susie pick out books for story time. Billy wants Mommy to read his favorite, Timothy’s Space Book. He loves to hear about rockets and engineers and the exciting future he’ll have as an ambitious, tough-as-nails astronaut. But his older sister wants Mommy to read her favorite, Space Flight: The Coming Exploration of the Universe. Susie likes the pictures of satellites and space planes and sandwiches floating in microgravity. Her favorite part is when Mommy reads the section titled “Spacemen”:

In the future, most boys will dream about going into space. The idea of being a spaceman will attract young people just as many now want to become airline pilots. Girls will also want to go out into the Space Service. They will probably do at least as well as men; for long and difficult trips, women may be preferred, since it has been proved that they are able to stand monotony better than men. Some girls may become pilots. The word spacemen must be used to mean either boys or girls, with no difference in the type of job they will do.

Susie drifts to sleep, imagining what kind of job she will do as a spaceman of the future. While this is the only one of the many children’s space books in her family’s library to mention girls and women, she looks forward to living and working in a future of space stations, interplanetary travel, and cosmic colonies.

In outer space, spacemen and sandwiches alike float free (top). No ladies here—though perhaps it’s presumed that they made the sandwiches, as illustrated in a 1960 conception of a future space station (bottom) in which three of four pictured female station inhabitants staff the cafeteria. Three decades later, in her co-authored children’s book To Space & Back (1986), America’s first woman astronaut Sally Ride pragmatically tells young readers that each astronaut must make his or her own sandwich in space, lest they drift apart before consumption. Top: Lester del Rey, illustrated by John Polgreen, Space Flight: The Coming Exploration of the Universe (New York: Golden Press, 1957). Bottom: Donald Cox, illustrated by W. A. Kocher, Stations in Space (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1960)

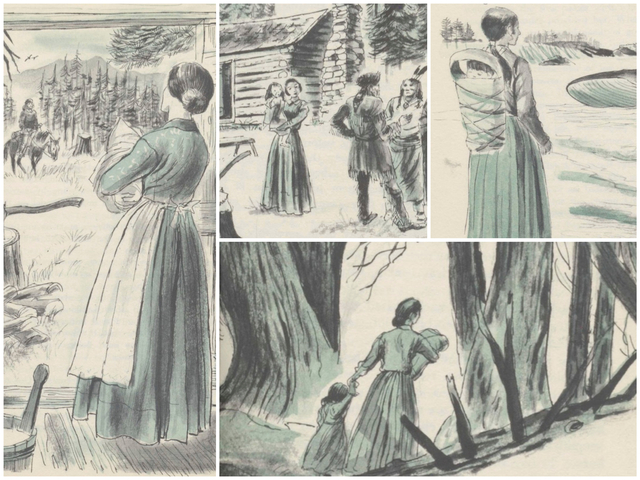

Mommy slides Space Flight back onto the shelf and pulls out Billy’s favorite Wild West storybook. Although the book in her hands portrays a nostalgic pioneer past that seems distant and alien in the modern 1960s, she feels a kinship with the bonneted, rugged women pictured. Her job seems remarkably similar to theirs, occasionally glimpsed in illustrations of wagon trails and homesteads from a century earlier. Next to valiant male explorers with their rifles and plows, pioneer women stand in doorways with a baby in arms, or trudge through prairie grasses with toddlers clinging to their skirts. When pictured at all, these women are evoked and defined solely by their reproductive labor.

It seems to Mommy that if a hundred years hadn’t changed her own primary contribution to American society as wife and mother, perhaps Susie might be setting her sights impossibly high.

Even the rare 1950s and 1960s children’s book that focuses on the “heroines” of the west represents women in the Western frontier as mothers first—or mothers only. Nancy Wilson Ross, Heroines of the Early West (New York: Random House, 1960)

In the living room, Daddy reads the New York Times. In response to publicity surrounding formerly secret medical testing of women to determine their theoretical fitness for spaceflight—and a Congressional hearing weighing whether women should be considered for astronaut selection during or after the Mercury program—a physician-journalist concludes that women could be just as fit spacefarers as the celebrated male Mercury 7 astronauts. But a single, all-important question remains: Why? Why send women into space at all when qualified men already do the job well?

Daddy chuckles at the answer given in the article:

“It appears inevitable that women will eventually be space travelers. If man is to colonize the planets, if celestial housekeeping is ever to be instituted, the ‘second sex’ must have booking on future space flights. Unless the National Aeronautics and Space Administration has in mind some drastic sociological innovations, the story of outer space cannot discard the traditional boy-meets-girl plot.”

The forward-thinking journalist imagines colonies in space, with humankind expanding its reach to the stars. However, even a medical doctor cannot imagine a future that separates women from their definitive biological identity as childbearers—such a future seems so “drastic” as to be unimaginable—in 1962 and today.

Celestial housekeeping as envisioned in a 1968 advertisement for cleaning products. The space suit may be mod, the implied setting futuristic, but the assumptions about how straight, white, domestic women will perpetuate the species (and straight, white, domestic culture) onto other planets reflects longstanding ideas about the imagined role of female pioneers that persist today. Noxell Corporation, 1968

The journalist’s answer may be tongue-in-cheek, but it’s also an accurate representation of standard reasoning regarding women’s primary utility as astronauts across decades and genres of popular and political discourse. Without women to give birth to new generations of strong, intelligent, moral Americans in space, the final frontier would be as good as closed from the start.

The reproductive labor of American women as the fulfillment of their civic duties—known as Republican Motherhood—provides a thread of continuity between the Western American frontier and the imagined final frontier of outer space. During the early days of the American republic, a political role for women evolved from the classical model of the Spartan Mother—a woman whose civic purpose drew from fashioning future soldiers to protect Sparta. The Republican Mother of eighteenth-century America could not vote, but she could raise responsible, civically engaged sons who would.

This idealized political role of women as Republican Mothers endured into nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century historical representations of the Anglo-American push into the Western frontier. Frederick Jackson Turner first publicized his Frontier Thesis at the end of the nineteenth century. In it, he claims that westward expansion played a major role in the formation of a twentieth century American identity of rugged exceptionalism. While women are notably absent from Turner’s thesis, subsequent revisions and elaborations of the Frontier Thesis portray frontier women as political actors by way of their power to reproduce, both physically and socially, a unique breed of American. The Cold War space race of the mid-to-late 20th century required a new kind of pioneer, but one that still expressed this frontier-forged American exceptionalism.

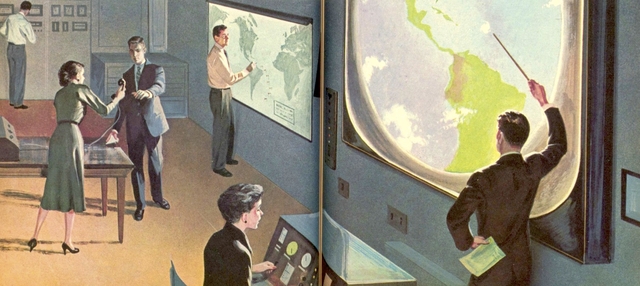

Lester del Rey, illustrated by John Polgreen. Space Flight: The Coming Exploration of the Universe. New York: Golden Press, 1957

In building an American cultural identity in a real or imagined vacuum, the quiet but clear social and political role of American women as nurturers of the next generation of upstanding American citizens extended into this latest, ultimate frontier. In the late twentieth century, journalists, popular writers, scientists, legislators, astronauts—Americans of all stripes—projected into the final frontier of outer space the same nineteenth-century frontier mythology that valued women pioneers as little more than reproductive cargo on the westward wagon trails.

The political output of the frontier-going Republican Mother. Edith S. McCall, Illustrations by Carol Rogers, Pioneering on the Plains (Chicago: Children’s Press, 1962)

Early space age culture in America highlighted women’s reproductive capacity as a primary, crucial contribution that women could and inevitably would make to the space effort. At a broader glance, the concept of women as essential reproductive payloads on space voyages seems deeply at odds with the high-tech fantasies of those suggesting it. Futurists of the early space age could imagine the entire universe as potential human habitat—they envisioned the terraforming of Mars, enclosed biospheres on the Moon, and space stations with artificial gravity. Whole new civilizations sprang forth from predicted technologies that pushed the limits of the known physical universe. However, the idea of removing childbirth from the human female body crossed a border between natural and unnatural that an agricultural space station did not. The limits of the broad-reaching extraterrestrial utopian imagination of mid-twentieth century America stopped at the biological boundary of human reproduction.

Before we shake our heads blithely and chalk this up to 1960s chauvinism, keep in mind that the role of women as interplanetary breeding technology persists in current American scientific and popular culture. Biological studies of the challenges of human reproduction in space have been periodically published in the intervening decades, with one article by NASA researchers on the subject published as recently as 2010. As of April 2014, the Wikipedia page for “Women in Space” is roughly half composed of discussions of motherhood in space—whether it is possible to become a mother in outer space, special risks for astronauts who are also mothers, and studies of mammalian reproduction in space science research. Recent and current science fiction franchises that peddle in spectacular intergalactic futurism, including Star Trek and Star Wars, still bank on the reliable ratings draw of dramatic childbirth. We continue to imagine a future in the stars. We are capable of great flights of fancy that strain logic and credibility—except when it comes to imagining gestation and childbirth taking place outside the female body.

Artist’s conception, circa 1976, of a proposed space habitat known as the Stanford torus. Note the family-friendly recreation area in the foreground, with children playing under the watchful eye of a Space Mother. Featured in Exploring Space, a children’s book published in 1979. NASA

In her groundbreaking book The Dialectic of Sex, Marxist-feminist scholar Shulamith Firestone pinpoints a biological root of gender inequality across cultures. Childbirth, and all its attendant risks, labor, and anxieties, renders women reliant upon men for support, thus reinforcing power imbalances in the larger culture. Only when the physical act of childbirth, and the burden of providing humanity with its biological future, is removed from the female body will gender parity become a reality. Arguably a technological utopian in her own right, Firestone in 1970 foresaw a not-too-distant day when reproductive technologies would free women from the shackles of childbirth, destroying the gender hierarchy once and for all.

Perhaps Firestone was too optimistic in her assessment that the technology to remove reproduction from women’s bodies might be imminently available. Pregnancy and childbirth as the exclusive, almost mythical realm of the female body continue to occupy a sacred place in American culture. Where fanciful technological fixes to social and ecological problems from food supply to energy shortages merit political discussion, topics touching on technologies of childbirth rarely arise without inspiring intense, often polarizing debate.

There’s something irrefutably natural about the act of gestation and childbirth that renders it controversial to liberal and conservative alike. On one side are those that would agree with Firestone that childbirth oppresses women; then there are others that see great power in the act of childbirth—that even in the 21st century the physical act of becoming a mother imbues women with unique political power inaccessible to men. Harnessing technical rhetoric to describe the flip side of this power, some critics of partial, assisted reproductive technology such as surrogacy or in vitro fertilization have voiced fear that, should Firestone’s vision come true, women will someday become obsolete like any other supplanted technology.

If women are no longer necessary to procreate, will there be a place for them in any imaginable future?

Cultural anxiety about the immutability of biological childbirth ran—and runs—so deep as to shape the broad scope of possible futures projected in the realm of fiction. Some of the most acclaimed twentieth-century popular American science fiction anticipates a dystopian future—with a major exception of the Star Trek franchise. Perhaps tellingly, iconic sci fi dystopian novels such as Brave New World and Dune feature future human societies that reproduce through technological means separated from the female body. Renowned science fiction luminaries from Isaac Asimov to George Lucas present artificial wombs as the pinnacle of futuristic inhumanity.

In the utopian interstellar future of Star Trek, by contrast, childbirth remains the exclusive domain of female human and humanoid members of Starfleet and the human-like species its members encounter. Female Starfleet members across all Star Trek series—and across inexplicably sexually compatible species—give birth in space. Even Captain Kathryn Janeway, the only female captain of a Star Trek series, cannot evade this unavoidable mark of her gender identity. Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, considered by some to be the Trek franchise with the most subversive, even queer politics, firmly situates childbirth as the exclusive domain of female bodies, even in scenarios where otherworldly, incomprehensible medical interventions allow fetuses to move from one body to another, or convergently evolved humanoid species to generate viable hybrid offspring together.

In Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Major Kira Nerys, a non-human Bajoran female, gives birth to the child of two human parents, originally conceived and gestated by the human birth mother before an accident necessitates moving the fetus to the only available humanoid surrogate. The assisted reproductive technology of the utopian space future enables interspecies surrogacy and mid-pregnancy fetal transfer, but still requires a fleshy womb for successful human reproduction.

Even in the expansive world of fan fiction and slash erotica, where the rules of gender and the physical universe are sometimes even more pliable, the female gendering of childbirth endures as an untouchable rule. In her analysis of Star Trek slash culture, cultural theorist Constance Penley looks at the practices and tastes of women peddlers of Kirk/Spock porn (also referred to as “K/S”). These writers and readers engage in subversive fantasies of futuristic, interspecies gay erotica in order to abandon the gendered inequality of the traditional “romance formula.” However, K/S pairings that result in one of the male pair having a baby never seem to gain traction or support among Star Trek slash aficionados. Overly complicated descriptions of convoluted technical rigs and participation by third and fourth parties render the process of a male pregnancy so awkward as to put off even to the most devoted slash practitioners. Most K/S fans find the suspension of disbelief required to imagine such profound rewriting of biological gender rules either impossible or unpalatable. Even in radical queer rewritings of utopian futures, the de- or re-gendering of childbirth crosses a line into the unthinkable.

One iconic space fantasy film of the 1960s represents a refusal of a future in which space women continue to be marked by their peculiar reproductive identities. While the sexy, campy Barbarella may not seem like a feminist political manifesto on its surface, the film does something very strange indeed: It imagines a spacefaring woman who is not only in control of her sexuality—but in control of a sexuality that is distinctly non-reproductive. Rather than serving as a means to expand the reach of humanity through producing more humans, intrepid astronaut Barbarella wields her sexuality as a tool of political exchange, and even one of pure, non-reproductive pleasure. This radical and dangerous concept in late 1960s America inspired protest and boycotts of the film by concerned conservative Americans. Like the women of ill repute in stories of the Wild West—women scorned largely for their ability to make a living outside the domestic sphere and exerting an economic power antithetical to Republican Motherhood—Barbarella makes her way into the final frontier not as passive reproductive payload but as a political actor equal among men.

In an iconic scene, Barbarella destroys the killer Excessive Machine using the power of her non-reproductive sexuality.

Perhaps it was the Barbarella-like infertility and non-reproductive power of pilot and astronaut aspirant Geraldyn “Jerrie” Cobb that put her interlocutors at odds with her strident argument that she and other women be considered for spaceflight. In the early 1960s, she regularly spoke in defiance of high-ranking NASA administrators who publicly argued that training women astronauts would be a “waste” and a “luxury.” Cobb’s singleness, childlessness, and tendency to lapse into feminine faux pas such as kicking her shoes off under the table might not have resonated well with the ideal of the female spacefarer as Republican Mother for the space age lauded by supporters of a theoretical women-in-space program.

Cobb had reason to believe that women would make excellent astronauts, even within the macho culture of the Cold War American space program. Starting in 1959, the medical clinic that tested Mercury astronaut candidates ran a group of women, beginning with Cobb, through the same qualification exams that the men underwent. While these exams were privately funded and did not represent any official move towards hiring women astronauts, the project came to public notice in 1962 when the U.S. House of Representatives held a hearing on the selection of astronauts, with the explicit goal of determining whether or not women had been intentionally excluded from consideration and deciding if women should be integrated within the ranks of the nation’s space pilots.

Over the course of the two-day hearing, the Special Subcommittee on the Selection of Astronauts of the Committee on Science and Astronautics heard from a range of space flight and aviation experts, starting with Jerrie Cobb. Cobb’s testimony detailed the raft of tests she undertook, from two days in an isolation tank to swallowing radioactive water to pedaling a bike until exhaustion set in. She also noted that she and twelve fellow female test subjects had matched or even surpassed the results achieved by the male Mercury 7 astronauts, though she was careful not to suggest that her gender made her superior to the newly minted American heroes.

Jerrie Cobb poses next to a Mercury spacecraft in this undated photo. Nearly four decades later, supporters would campaign for her to become an astronaut prior to John Glenn’s historic return to space aboard the Space Shuttle in 1998, arguing that experiments on space geriatrics should include women, who make up the majority of the elderly in America. The campaign did not succeed. NASA

While the legislators in presence responded positively to Cobb, they spoke with extra deference to the next speaker—Jane Hart, a senator’s wife and mother of eight children who also successfully passed the suite of Mercury medical tests. A model of Republican Motherhood, her potential as the perfect space colonist did not go unnoticed even in the austere setting of a Congressional hearing.

Mr. ANFUSO: Miss Cobb, that was an excellent statement. I think that we can safely say at this time that the whole purpose of space exploration is to some day colonize these other planets and I don’t see how we can do that without women. [Laughter.]

Mrs. HART: I would like to say, I couldn’t help but notice that you call upon me immediately after you referred to colonizing space.

Mr. ANFUSO: That is why I did it. [Laughter.]

Representative James Fulton, the most outspoken member of the committee in support of Cobb and Hart, invoked the names of legendary pioneering women in arguing for including women in the American space effort. From Queen Isabella to Sacagawea, Fulton argued that women provided greater services than his colleagues would acknowledge—women generated capital, performed essential labor, and displayed quick thinking in frontiers across history, concluding that “ladies can be courageous for various reasons in space.”

Damning counterevidence came in the form of testimony by the funder of the women’s medical exams. Jacqueline Cochran was a famous aviator of her time. Wealthy, accomplished, and sharp as any pioneer woman invoked by Fulton, by the end of her life she held the greatest number of flight records by anyone, man or woman. She organized the Women’s Air Service Pilot (WASP) initiative during World War II. She was a personal friend of Chuck Yeager and Dwight Eisenhower. Cochran believed that while women might be physically and psychologically fit for space flight, their primary dedication to domestic roles as wives and mothers made them a poor investment by the cash- and time-strapped space program. She testified as such to the assembled committee, to the shock and consternation of Cobb and Hart.

Cochran’s testimony was followed the next day by that of John Glenn and Scott Carpenter, two recently returned astronaut heroes who expressed clear opinions on whether or not to change existing astronaut selection guidelines to allow more women to be eligible. John Glenn particularly noted his belief that passing the medical exam did not make the women test subjects “automatically astronauts,” stating:

It just shows that they are a good healthy person. These [exams] are such a minimum thing…A real crude analogy might be… My mother could probably pass the physical exam that they give preseason for the Redskins, but I doubt if she could play too many games for them.

Glenn invoked his own mother as proof of the absurdity of allowing a group of exceptional women to join an elite club, rendering them wholly unexceptional by association. The banality of motherhood presented by Glenn combined with the indisputable prioritizing of motherhood at the expense of flying professions presented by Cochran did not help Cobb and Hart’s case. Instead it lent a contradictory valence to the debate about women’s fitness and utility for spaceflight. Women’s reproductive capacity constituted both an accepted eventual necessity for their inclusion as spacefarers, but also the main obstacle to their immediate employment as astronauts. So long as childbirth took place after a future point of extraterrestrial colonization, women could become welcome, contributing members of spacefaring society. Their fertility both limited and necessitated their participation in a spacefaring American future.

After the hearing, which was cut short by a day following the astronauts’ celebrity appearances, the matter seemed closed. Meager attempts to jumpstart a woman in space initiative met lukewarm to downright hostile response among the ranks of the federal government. The first woman in space would be a Soviet, Valentina Tereshkova, who orbited the planet a year later. It would take another 20 years until an American woman would follow in her footsteps, and another fifteen years after that until the first American woman would command a space mission.

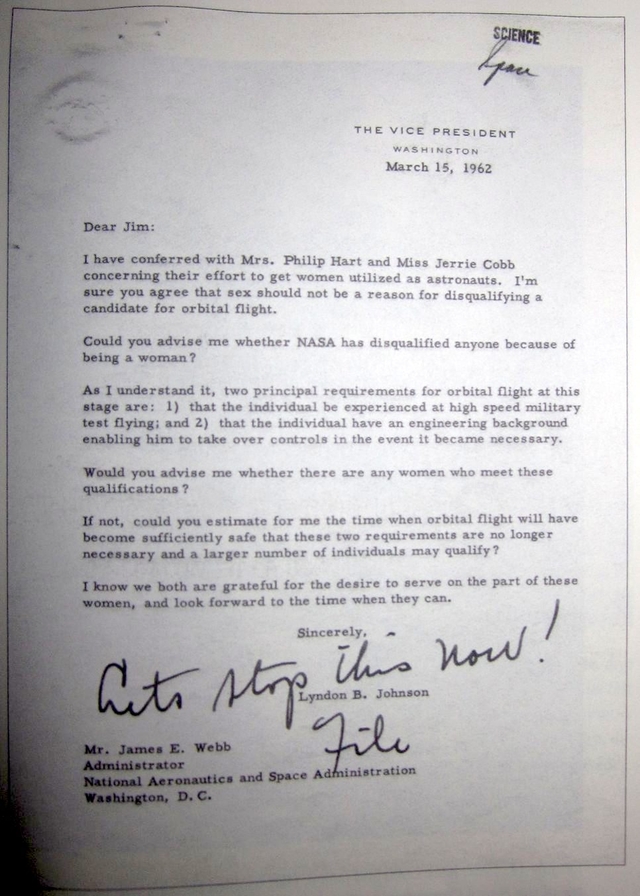

Written four months before the Congressional hearing on astronaut selection, a letter to NASA Administrator James Webb drafted by Lyndon B. Johnson’s secretary on the topic of investigating a possible program for women in space gets filed away, unsent, with telling marginalia in the Vice President’s hand. Cobb and Hart faced an uphill battle from the start. NASA History Office

That first woman spaceflight commander, Eileen Collins, credits science fiction for expanding her ideas of what human futures in space could look like. Perhaps our fictional Little Susie also turned to Star Trek to find a place for herself in the cosmos, even as its radical representations of women across race, class, and creed as fictional or real spacefarers retained gendered marks of fertility and reproductivity.

It may take Susie growing up into Susan, getting radicalized by reading Simone de Beauvoir, and joining a consciousness-raising group to realize that even in her beloved childhood picture books, the only women pictured engaged in space labor are answering phones, serving food, and sewing spacesuits, feet firmly planted on the ground. In the 1980s she will have Sally Ride and Shannon Lucid to look to for inspiration, real women who flew in space in spite of, not because of, their ability to give birth—even as the popular press attempted to highlight that ability above all others. In the 1990s she will have fictional Captain Janeway and Major Kira Nerys, who participate fully in galactic politics even as they give birth in alien places under strange and fantastic circumstances. In the 2010s, Susan will see a new group of astronaut candidates, the first cohort in history to be made up of an equal number of men and women. She will also notice that the vastly lower total number of women astronauts boast higher levels of education and qualifications compared to the men that make up the significant majority of the astronaut corps.

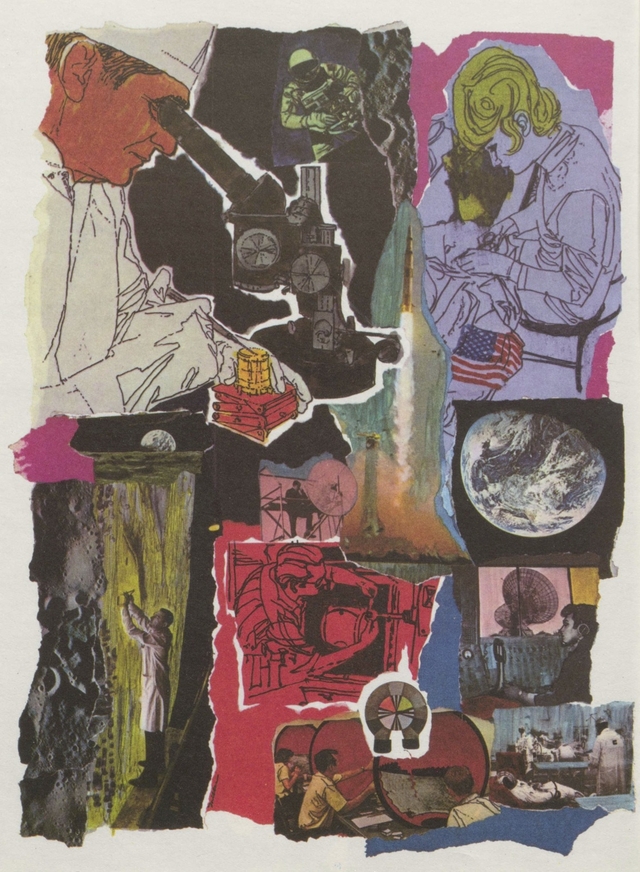

Men and woman (singular) at work in the space industry, as imagined in 1969. Leroi Smith, ed. We Came in Peace. (San Rafael, Calif., Classic Press, 1969)

A new millennium of self-perpetuating human colonies on Mars imagined by 1960s space-age futurists has not yet come to pass, nor has the alternative radical feminist fantasy of gender equity through artificial reproductive technology. Astronauts of all genders continue to be transient visitors, not permanent residents, of outer space. Pregnancy in space remains “contraindicated” in deference to the unknowns of what a microgravity and high radiation environment might do to fetal development. The intergalactic futurism of the Cold War space race has mellowed into legislative debates over whether the Moon, Mars, or an asteroid should host our next celestial visit, with no serious proposals of imminent extraterrestrial human civilizations. The latest projections of the next era of American human spaceflight reflect more pragmatism and ambivalence than the sweeping cosmic visions of the 50s and 60s.

For better or worse, these futures may be less immediately contingent on physically sustaining the frontier narrative into the universe. Will today’s Little Susies be able to imagine a future in space liberated from their procreative responsibilities? Will the astronauts of the next centuries be Jerrie Cobbs, Barbarellas, or Kira Neryses? Or will even visions of grand future civilizations in space continue to be confined within the wombs of the next generation of long-suffering frontierswomen?

A 1973 children’s book stars a young girl of color who makes her dream of spaceflight a reality through ingenuity, imagination, and a little gaming of the very system that would exclude her—the heroine builds her own spaceship out of salvaged junk, and travels solo under no expectations but her own. Here’s hoping Susan picked up a copy of this exceptional book for her daughter. Linda C. Cain and Susan Rosenbaum. Blast Off! (Lexington, Mass.: Ginn, 1973)

Further Reading:

Joyce Chaplin on “terrestriality” and the dangers of space flight in our fifth issue, “Bodies.”

Matt Goldmark on Star Trek’s colonial inspirations elsewhere in this issue.