The Passing of the Indians Behind Glass

Why natural history museums are taking down their indigenous cultures dioramas—and what can take their place. University of Michigan Museum of Natural History

Late fall is Indian history season, Veronica Pasfield says knowingly. In the run-up to Thanksgiving, public schools always teach kids about Native Americans. In November 2001, Pasfield’s son’s third-grade class in Ann Arbor, Michigan, started a unit about a Great Lakes people called the Potawatomi. They visited the Great Lakes Indians dioramas in what was then called the Exhibit Museum of Natural History in Ann Arbor for their final activity.

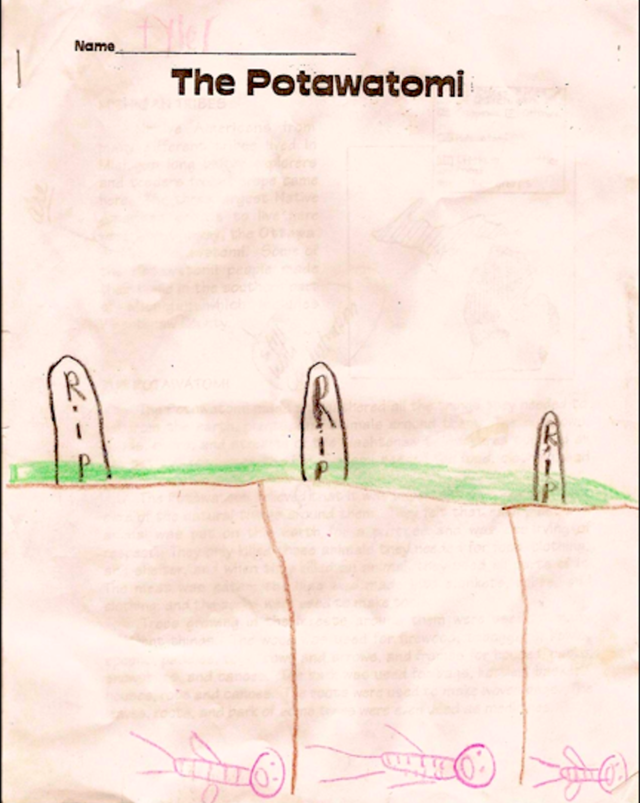

Afterward, the boy illustrated the cover of his folder that contained all the worksheets from his unit on the Potawatomi Indians. He drew three deep graves with skeletons at the bottom and tombstones that said “R.I.P.”

“This was devastating to me as a mother,” Pasfield says, “because my son is an enrolled tribal member.” The family belongs to the Bay Mills Indian Community. They are also Anishinabe, a grouping that includes the Potawatomi. “He has been ritualized properly for his age. He has been a participant in ceremony his entire life.” They had taken him to language classes. He had helped build a community canoe. Yet something about seeing the Exhibit Museum’s wall of glassed-in, miniature Great Lakes dioramas made him think of death.

He wasn’t alone. Shannon Martin, who is also Anishinabe, explains how she felt as a kid, when she saw American Indian exhibits in natural history museums: “It sounded like we were an ancient people and that we didn’t exist anymore.”

Pasfield talked with other parents, both Native and non-Native, and found many of their kids had similar misconceptions after their field trip. So she took her son’s drawing to museum staff, starting a years-long campaign to get the museum to remove the dioramas from display.

It turned out that the Exhibit Museum, re-named the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History in 2011, was one of the last to do so. Dioramas of indigenous cultures have been disappearing from natural history museums worldwide since the 1990s. That decade saw the shuttering of indigenous dioramas in the Cranbook Institute of Science in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. In the South African Museum in Cape Town, staff covered their famed Bushmen diorama with plywood and refused to show it even to a museum studies researcher and his class when they visited, says Amy Harris, director of the University of Michigan’s museum. The Smithsonian Institution took down their dioramas in 2002.

Visitors and museum staff say that by displaying American Indian cultures alongside dinosaur fossils, gemstones and taxidermied animals, dioramas make their subjects seem less than fully human. And because they depict a culture in a freeze-frame moment in time—often during the seventeenth century, around when many tribes first contacted Europeans—they make children think that all the American Indians are dead.

But what also disappears with the people and scenes behind the glass? “Dioramas are a very, very powerful mode of representation,” says Raymond Silverman, director of museum studies at the University of Michigan. Dioramas are fully realized, crafted worlds. They’re full of details, rendered in 3-D better than any movie. “They force one to look closely, especially in miniature,” Silverman says. “Imagine an entire village scene in 100 cubic inches.” Dioramas draw viewers in, inviting them to look for the exact same things that people seek in any new situation. Who’s talking to whom? What are they doing there? Who do I think could be my friend?

At their best, dioramas are like time travel. And some say there might just be a way to replace them, responsibly, before they are as lost as the worlds they claimed to portray.

To understand dioramas’ future, we need to understand their past. How did dinosaur fossils, gems and minerals, taxidermied wildlife and indigenous people all end up in the same museums in the first place? More than unconscious bias mixes American Indians with apatosaurs.

Unlike the displays at the Exhibit Museum, most dioramas were created between the 1890s and the 1930s. Some museums, such as The Field Museum in Chicago, took in dioramas that had been shown in the popular World Expos. Before photographs, films, and cross-country family vacations were common, dioramas allowed museums to show people faraway places. At the American Museum of Natural History in New York, curators commissioned their animal dioramas out of a growing fear that America’s natural lands were being destroyed. They wanted people to see and appreciate those habitats before they disappeared. “Railroads were opening up the country at this time, the great western frontier was disappearing, the vast bison herds were vanishing,” an AMNH senior project manager recently said in a museum-produced podcast. “So the scientists and curators in science museums that were concerned about vanishing wilderness and wildlife were looking for some medium to tell the story.”

Scientists of the time had similar worries about American Indian people. Before and during the turn of the twentieth century, the U.S. government was often at war with different American tribes and federal policies worked to stifle American Indian cultures. In 1879, the government-funded Carlisle Indian School opened in Pennsylvania. With the stated goal “to kill the Indian, and save the man,” the boarding school forbade its young students from speaking their native languages. It forced them to attend church and wear European clothes. Carlisle students were abusively, physically punished for infractions. Over the next two decades, the U.S. government opened as many as 100 similar boarding schools across the nation. Carlisle processed more than 8,000 American Indian children; its counterparts accounted for tens of thousands more.

In 1887, the Dawes Act forced individual land ownership on American Indian adults to further their assimilation and to open up “extra” land to white settlers. The new landowners were expected to farm, whether or not they came from farming cultures and in spite of the fact that the land they were given was often in deserts.

Under these pressures, and as more and more people died in wars or of disease, the survivors began abandoning villages. Anthropologists raced to collect the things they left behind. “Our stuff was being scooped up right and left,” says Anishinabe member Shannon Martin, who directs the Ziibiwing Center, an Anishinabe cultural museum in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan.

Anthropologists were suddenly seeing a supposed need for “collecting the remnants of the ‘vanishing race,’” says fellow Anishinabe member Pasfield, who finished her doctorate in American studies at the University of Michigan last year. The 1893 Columbian World Expo in Chicago included an American Indian village display to show visitors an “almost extinct civilization, if civilization it is to be called,” as one guidebook explained. The expo hired people to wear traditional clothes that tribes had abandoned three or four generations ago. While the U.S. government worked to erase American Indian cultures, American museums tried to store them safely under glass: in natural history museums like fossils, in dioramas like dinosaurs.

“Dioramas hold up a mirror to their creators more than portray some kind of reality,” Pasfield says.

Of course, modern visitors of natural history museums don’t go in with these ideas in mind. But the stamp of injustice still lingers in the displays. These beautiful, 50- or 100-year-old dioramas are a holdover—and a subconscious reminder—of some of the worst moments in U.S. history.

At first, museum director Harris did everything she could to keep the University of Michigan’s Great Lakes dioramas. She and her staff rewrote their labels. “That took a long time,” she acknowledges. She convened an advisory board that included Native people. She hired a consultant from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. She worked with tribal members to develop an improved elementary school history program. She tried adding a display about contemporary Great Lakes culture, showing modern powwows, to address criticisms that dioramas only showed the past. “Even after that, we still got complaints.” The dioramas were so compelling they seemed to overpower whatever modern displays she created.

In the end, she realized they had to come down. She announced the anticipated change in September 2009 with press releases and a short video that aired on the local news. For a semester, the museum showed a “Native American Dioramas in Transition” display to explain Harris’s decision. Then, in January 2010, museum staff carried the dioramas down into the museum’s basement. They had been a part of the institution since the 1950s.

When they were on display, the dioramas were a series of fourteen miniature boxed scenes, each about the size of a large television. The scenes showed tiny figurines of Great Lakes and other American Indian people cooking around a fire, putting up a teepee in a snowy wood, and kneeling on staked-out leather hides to scrape and cure them. A baby napped inside a carrier patterned with blue and red flowers. One woman brushed her hair away from her shoulder with her hand, some strands tangling in her fingers.

The dioramas were arrayed in two long rows, stacked on top of each other. Each was lit from the inside; collectively, they glowed a faint green from all of the trees and grass depicted in the scenes. From a distance, they looked a little like a wall of tanks in the fish section of a pet store.

Museum staff say they were beloved by Ann Arbor residents, second only to the dinosaurs in popularity. When they were taken down, “the majority of our visitors were really unhappy,” Harris says.

“It saddens me greatly that we would not have these dioramas anymore,” Ann Brill, a fourth-grade teacher in Dexter, Michigan, wrote in a comment to the museum. University of Michigan archaeologist Lisa Young scanned and shared the comments over email. “We cannot take our students back into time to experience firsthand the life of our country’s natives; … the dioramas offer a wonderful visual aid,” Brill wrote.

“No museum director ever wants to do anything that makes the majority of museum visitors unhappy,” Amy Harris says. But she takes full responsibility for her decision: “I think it was the right one.” Veronica Pasfield was pleased with Harris’s response. What used to be the museum’s Great Lakes hall now holds an exhibit of large mineral samples.

Yet some museum staff members say that ordinary displays of artifacts cannot fully replace dioramas. Dioramas show objects in action—a basket on a shelf doesn’t tell a museum visitor as much as a basket being carried by a person, a basket being filled with wild rice gathered on the shore of Lake Superior, or a basket getting woven in a home.

Dioramas are created with a seemingly bygone level of care and attention, fitting for a craft more than 100 years old. Every last minuscule detail, from baby blanket to braided pigtail, is handmade. Robert Butsch, a zoologist who worked at the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History for 32 years starting in 1954, created their dioramas. At the time of his death in 2006 at age 91, he was working on a Pennsylvania coal forest scene for the museum. In an age when children and adults spend so much time looking at images and videos online, it still gives people pause to see Butsch’s handiwork.

At least one Native American visitor agreed, writing in to protest the dioramas’ removal: “My name is Joseph [Last name redacted by Young]. Oglala Lakota pipe carrier, sun-dancer, Holy man, and singer. I have enjoyed these dioramas with my children for many years … . Truly it idealizes a way of life we will never have again.”

Elsewhere, however, more respectful ways of visualizing the indigenous past have developed.

In the northwestern-most corner of the contiguous United States, on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington state, the land meets the Pacific Ocean on cold, yellow, scrubby beaches, where evergreens grow almost right out to the salt water. Before they met Europeans, the Makah tribe lived here for more than 3,800 years, plying the rough ocean in canoes carved from Western red cedar. They fished and hunted porpoises, seals and several species of whales. They carved small canoes for kids to practice navigating.

In the winter of 1969-1970, hikers visited the beach here after a storm had washed some of the beach mud out to sea. They discovered the erosion had exposed some long-buried wooden artifacts. One hiker called the Makah Nation and Makah officials called Washington State University in Pullman. In April, university archaeologists began excavating the site by washing away the mud with seawater.

Makah oral tradition had long talked about an ancient “Great Slide” that buried a part of one of their villages. This was the buried section. It was a part of Ozette Village, in which people lived until 1917, when families left for the town of Neah Bay so they could send their children to school, as required by U.S. regulations.

Archaeologists determined the buried Ozette artifacts were about 500 years old, dating from before European contact with the Makah people. Over eleven years, the archaeology team unearthed six longhouses, 60-foot-long cedar buildings where many generations of one family lived. Inside and around the longhouses were 55,000 artifacts: bits of everyday life, from wooden bowls to colorful baskets to one carved wooden whale dorsal fin decorated with 700 evenly-spaced otter teeth, the purpose of which is still unknown.

Washington State University archaeologist Richard Daugherty examines an artifact found at the Ozette Village archaeological site, Neah Bay, Washington. Photo courtesy Harvey Rice/Washington State University

The Makah Tribal Council decided to create a cultural center to care for and display these artifacts. The center would be more than a museum; it would also house the basket weaving and language classes that had previously been scattered throughout the reservation. Council members met with an exhibit design company from Victoria, Canada, and in 1979, they opened the Makah Cultural and Research Center at Neah Bay.

The center was one of dozens of Native-run cultural museums that opened in the Americas that decade. Most non-tribal anthropology museums, however, continued to use the traditional dioramas. The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History kept 1950s and 1960s-era Native American exhibits until the early 1990s, when museum staff, for the first time, asked Native artists to write and record explanations of the Seminole textiles and Mohawk baskets the museum had on display. At that time, the tides began turning for how museums showed Native culture and history. One major signal of change was the 1990 passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which compelled museums and federal agencies to let tribes know if their collections held tribal items.

First Nations-run museums continued to open throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Now there are about 200 of them in the U.S., Canada and Mexico.

The Makah Nation may have been among the first to display their own cultural objects, but Janine Bowechop, executive director of the cultural center, says they never considered anything else. “We would never give this collection away,” she says. “This collection is really a treasure of our tribe. They were made by Makah people. They were excavated from Makah territory. We’ve done a great job in taking care of the collection and in using it to interpret culture, to preserve culture.”

When visitors walk into the museum portion of the center, one of the first things they see is an eight-foot-long scale model of the buried village. Though it includes tiny people, halibut drying on racks, and canoes on the beach, Bowechop says it’s a scale model, not a diorama. “It helps people understand the layout of the village,” she says.

After the scale model, the museum takes visitors through what pre-contact Makah people did from season to season. The first displays show artifacts related to springtime and the whale hunt. There’s an actual diorama, showing taxidermied Steller sea lions, that’s mostly notable for its flood of lighting in a museum typically kept a bit dimmer than most to protect the 500-year-old objects on display. Fishing and seal hunting shade into summer. Next come cases with tools and art made and used in the fall and winter. The museum uses text panels and photographs to show how the artifacts were used. There are two recently carved canoes with paddles and tools inside, which visitors can pick up. Kids who visit can make their own paddles to take home.

What the displays lack are full-sized Indian mannequins. “It was deliberate not to have mannequins,” says Jean Jacques André, founder of André & Associates, the design company that worked with the Makah Tribal Council. “It was out of the question to single out a person or persons to represent their ancestor.”

Bowechop, who was a teenager when the center opened, says she’s glad her predecessors made that choice. She doesn’t like “these orange-looking Indians in the displays.”

One of the Makah Center’s highlights is the full-size replica of a longhouse that visitors can go inside and explore. Cracks in the roof let in light and let out smoke. It’s dim inside, just as pre-contact longhouses were. Fire pits are located just where they were in the buried structures. “It’s turned out that it’s a really nice feature because so many of our artifacts are behind glass,” Bowechop says. “When you have an exhibit that you can walk inside, it really helps people understand what life was like.”

Although many tribal museums and their counterparts now avoid dioramas altogether, re-envisioned cultural exhibits like those at the Makah Center live on in many institutions. Life-sized, walk-in structures appear in The Field Museum in Chicago and the Ziibiwing Center in Mt. Pleasant, Michigan. The structures bring objects to life in a way that usual displays can’t, by taking things off museum shelves and tucking them just where they would be stored in a house. The walk-in displays replace some of the functions of older dioramas.

Ziibiwing Center leaders discussed dioramas extensively before they opened in 2004. They settled instead on more open displays, populated with life-sized mannequins that can be updated as Anishinabe culture changes. The displays are spread along the sides of the main, curving pathway where visitors walk. They show pre-contact Anishinabe people and Anishinabe activities through the seasons. Photographs and artifacts show the colonization of Anishinabe land by white Americans, while modern Anishinabe-made artwork show the tribe’s current culture. None of the mannequins are inside glass cases. “We wanted to stay away from the whole idea of Indians behind glass,” says Martin, the center’s director.

The mannequins are all modeled after Anishinabe people living in the U.S. today. “We had kind of a casting call for our tribal community,” Martin says. “The mannequins are real tribal member likenesses, individuals who volunteered to come in to get headshots and get measured.” They are rendered in a terra-cotta monochrome. Their stylized hue helped the center avoid representing skin color—the issue that unsettled Bowechop, the executive director of the Makah Center.

Tribal members voiced all the recordings in the museum. Modern tribal artisans made all the clothes the mannequins wear and reproduced sacred objects that can’t be shown publicly, such as religious scrolls. The rest of the objects shown are authentic. In a walk-in lodge display, hidden smoked hide and cedar oil diffusers even give the building the right smell.

Yet in spite of all the thought and effort that have gone into American Indian dioramas since the 1980s and 1990s, there is no consensus about what works best. Bowechop dislikes full-sized mannequins and emphasized that the Makah Center doesn’t use any. Some critics of the University of Michigan displays thought miniaturization was problematic because it trivialized American Indians.

These disagreements arise because dioramas aren’t the soul of the problem. The problem is the culture that put American Indians in dioramas in the first place—in natural history museums, alongside the dinosaurs, in these sometimes-beautiful, contained worlds meant to record what the assumed viewer’s ancestors had wiped out. Different museums and cultural centers try to move away and move on from that history in different ways.

Moving on doesn’t mean forgetting, however. Displays such as modified dioramas and walk-in buildings maintain the older dioramas’ power to capture the imagination and show what life was like in the past. For scholars who want to see and think about how we used to display American Indian cultures, the University of Michigan’s Great Lakes dioramas are available for academic study in the basement of the building.

Some of the skills behind diorama-making also live on. Besides its sea lion scene, the Makah Center has one other display that Bowechop calls a diorama. At the end of the longhouse, a doorway opens out onto a painted background of the Pacific Ocean. Sculpted seagulls hang overhead on translucent wires. It’s meant to give visitors a sense of what it was like to live on the edge of the open ocean, something they cannot see where most Makah people live today. Neah Bay, where Makah villagers retreated when told to send their children to school, sits on the Strait of Juan de Fuca, not the open Pacific. For non-Makah visitors, it is a diorama in which the viewer doesn’t examine the Indian under glass, but takes her place.

For the Makah, it’s a window to what their ancestors called home.