Party Like It’s 1999: Japanese Retrofuturism and Chrono Trigger

Like most of you reading this, my memory is imperfect.

I forget names, faces, and especially birthdays. Perhaps this is because much of the limited storage space in my hippocampus has been crowded by bits of pop culture trivia. The largest cohesive body of knowledge within this dubious archive is of the animated program The Simpsons—still on the air since its debut just a few weeks before 1990. In many ways, The Simpsons nurtured my web of associative thinking. I learned as much from the show’s often highbrow references as I did from school curricula. So it was only natural that the show should be my cultural anchor when I started to consider the theme “Futures of the Past.”

My thoughts turned to the 1996 episode, “A Fish Called Selma,” in which Bart and Lisa’s always-unlucky-in-love aunt Selma marries a washed-up 1970s actor, Troy McClure. McClure lives in a hexagonal UFO of a home—actually a repurposed aquarium supported by rickety beams. The house, like McClure’s career, is falling apart, and is one broken support beam away from collapse. But humdrum Selma is starstruck. Upon crossing the threshold of her marital home, she is awed by the cheesy opulence. “It’s so modern,” she remarks. “It’s ultra modern, like living in the not-too-distant future.”

I find this same not-too-distant future wherever I see gravity-defying glass architectures, wherever Jetsonian disc-buildings hover precariously on over-tall spires. The not-too-distant future is all around us, but some of it has already become the all-too-recent past.

I recently wrote a book about a videogame called Chrono Trigger, first released in Japanese for the Super Famicom game system in March 1995, and later that year in English for the Super Nintendo, the Super Famicom’s blockier North American cousin. Chrono Trigger is a role-playing game about a disparate crew of heroes traveling through time to stop a cataclysm in the year “1999 AD.” In the game’s mythos, this year will mark the apocalyptic reemergence of legendary beast Lavos from the planet’s core. The characters journey through time to save their world from destruction.

Chrono Trigger is a product of Japanese imaginations, and we might be tempted to read this apocalyptic event as an analogue to natural disasters that have plagued the island nation. The most recent high-profile calamity was the tag-team manmade/natural disaster of March 11th, 2011. On that day, a tremendous earthquake triggered a coastline-devastating tsunami, which in turn surmounted the walls at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, causing significant damage and a meltdown of half of the plant’s reactors. This disaster was deeply palpable for me, a former resident of Fukushima with friends still living in the prefecture.

Before Lavos erupts and dooms the planet to perpetual nuclear winter by 2300 AD, the player gets a brief glimpse of that fateful year 1999 AD. Society has advanced considerably since the time period in which we begin the game—1000 AD, “the present.” But the domed cities dotting the landscape where towns and castles once stood are made less fantastic by evidence of spreading desertification. It is a subtle detail, and one not on screen long enough to permit most players—many of whom might be children and younger teenagers with more interest in gameplay than criticism—a close inspection.

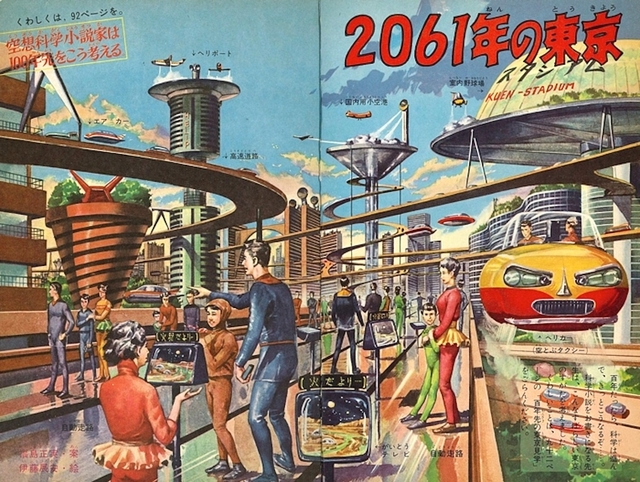

Similarly, nuance isn’t easy to come by in other 20th century Japanese visual renditions of the not-too-distant future, many of which were aimed at young readers. One striking vision of the future captioned “Tokyo in the Year 2061” features a panoply of classic science fiction tropes: hovercars, towering buildings with top-heavy platforms, smiling monoracial citizens in equally monochrome jumpsuits. There is nothing sinister here—except perhaps an instance of ghoulish pareidolia involving a grinning flying car—and indeed this image was published in a 1961 issue of a magazine called Tanoshii Yonensei, or “The Fun Fourth Grader.”

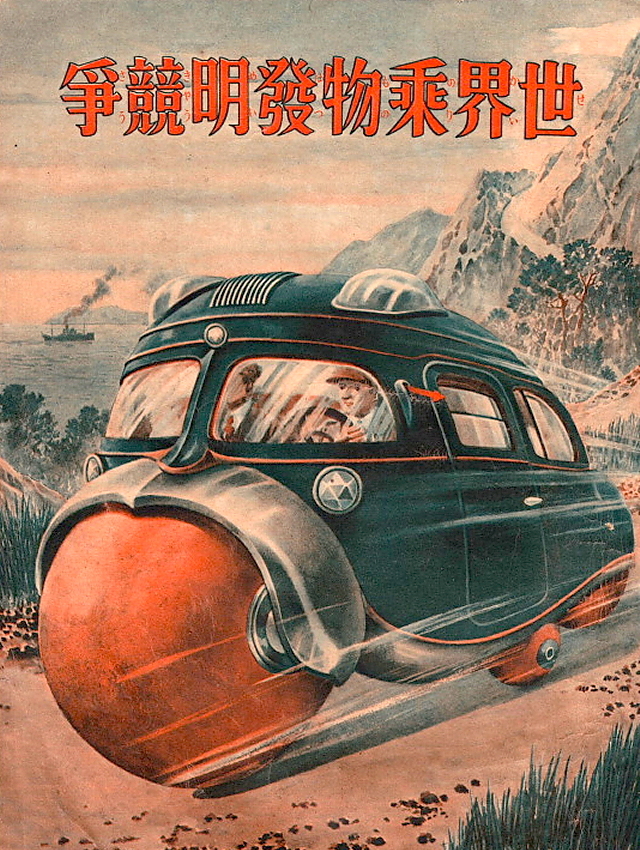

This is far from the oldest Japanese juvenile future I’ve encountered. A 1936 survey of future transportation published in the magazine Shōnen Kurabu (“Boys Club”) features a series of Japanese illustrations interpreting American and German inventions as part of a “World Transportation Invention Competition.”

Some machines, like the “amazingly swift flying machine,” still look revolutionary. Others, like the “sphere-wheeled car,” seem like dead ends of vehicular evolution.

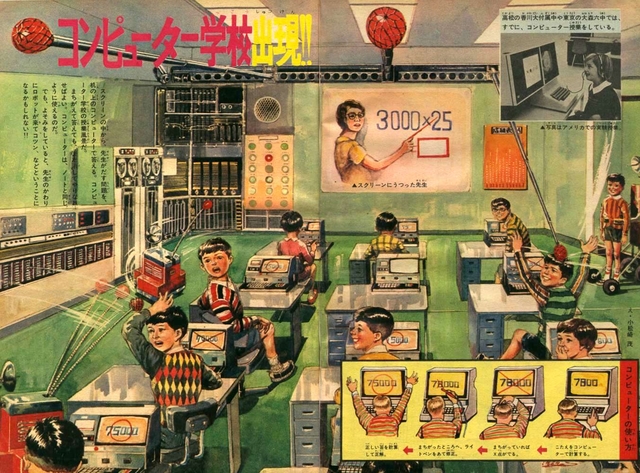

None of these curvilinear vehicles make an appearance in “Computopia,” published in a 1969 issue of another boys’ magazine, Shōnen Sandē (“Boys Sunday”). Instead the reader is treated to a transhumanist survey of the future of 20 years from then—that is, 1989. Boxy robot proctors patrol teacherless classrooms, bonking the noggins of children who input the incorrect answer on their computerminal desks.

For the purpose of maintaining order, the future classroom will come equipped with watchful robots that rap students on the head if they lose focus or act up,” Shōnen Sunday, 1969. Darkroastedblend.com

Meanwhile at home, a bubblegum machine-like kitchen robot enacts mundane tasks, as a technicolor-jumpsuited Mom takes care of home economics on a punchcard calculator. Yes, there are silly bits, but there is also striking prescience—a surgeon performing a delicate heart transplant using a guided computer arm, a self-propelled vacuum scouring the floor for debris, and Dad chatting on a videophone. While none of these futures had come to pass by 1989, they would be implemented within the next two decades.

The early 1970s Japanese book series Nazenani Gakushū Zukan (“Whywhat Illustrated Encyclopedia for Learning”) features more fantastical takes on possible futures and alternate presents. The volumes in the series juxtapose the realistic and the fantastic—a UFO whizzing past the Great Sphinx of Giza, or a giant dragonfly used as a rocket-powered airplane.

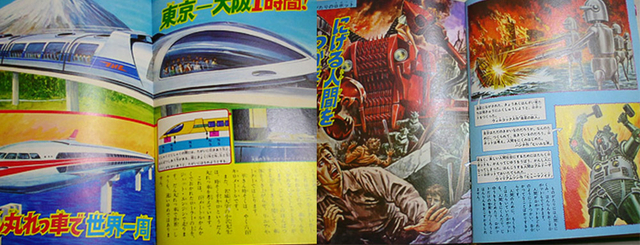

The volume which drew my attention was number 14, Robots and Life in the Future (Robotto to Mirai no Seikatsu), published in 1973. Used copies are prohibitively expensive and difficult to have shipped from Japan, and no library in the United States seems to own this volume. I was, however, able to find a digital preview of its contents. The first section depicts what it calls a “bright future,” where robots labor on moon colonies and humans zip from Tokyo to Osaka in one hour on a massive bullet train. The second, the “dark future,” shows laser-armed robots revolting against their selfish human masters.

Bright and dark futures of high technology juxtaposed in the pages of the 1973 book Robots and Life in the Future. Shōwa Nabi

The final image of the dark future is a two page spread: the first shows a global ice age, with Tokyo Tower (or is it the Eiffel Tower?) drooping defeatedly to the ground; the second depicts a series of transparent domes on a barren landscape, sustaining both the ecosystems and the cityscapes within them under artificial sunlamps. While this book was undoubtedly designed to be read right to left, the decontextualization of these two pages into one image shows a frightening synchronicity. These domed cities could just as easily pass for Chrono Trigger’s 1999 AD, and the wintry desolation for its 2300 AD. Here in the Whywhat? series, these dark futures are one and the same, separated only by the gutter of paginal transition.

Most of these original sources are difficult to find, and I do not doubt that many undiscovered gems are still buried within unindexed library-bound journals or the bins of Japanese used bookstores. The most fascinating thing about these images is not what they got right or what was way off, but rather that humans today are so captivated by them. The force that drives up the price of these collectibles—perhaps the very same quality that imbues them with collectibility in the first place—is nostalgia. Nostalgia for a past of which I wasn’t a part. Nostalgia that imagined futures in which nostalgia for the past would become obsolete.

One element conspicuously lacking from mid-century Japanese visions of the future was play. Almost every character in these images is doomed to a sedentary lifestyle, and their activities are either productive of, or passively receptive to, information. There is nothing fun about Computopia.

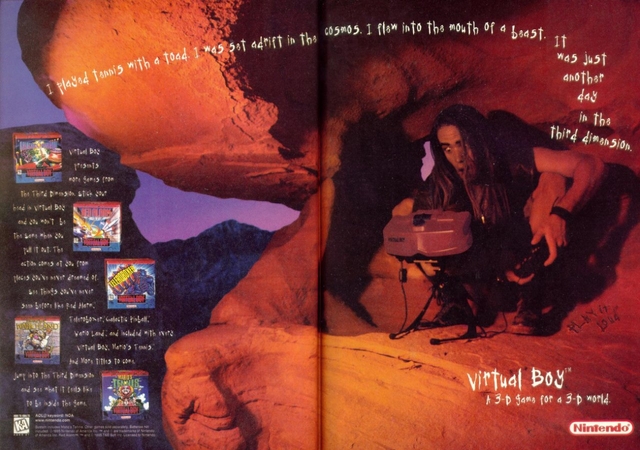

A caveman-like Gen Xer discovers the three-dimensional wonders of the Virtual Boy, 1995. Nintendo Life

Even Nintendo’s mid-90s game system flops were futurist. The Virtual Boy, a system that aimed to be portable and to create virtual experiences, managed to fail on both accounts. Not only was this ViewMaster lookalike incredibly cumbersome, it was not even wearable—players had to place the device on a flat surface. Even worse, graphics generated by the device were only red and black, and rumors abounded of players developing severe headaches. Even with continuing discounts on its initially hefty price tag of $180 in 1995 dollars—Toys “R” Us eventually started selling the system at $25 after poor Christmas season sales—the Virtual Boy failed to attract an audience and was soon retired from production. Despite inspiring modern successors like the truly portable, stereoscopic Nintendo 3DS, the Virtual Boy was by most accounts a spectacular failure.

While 1995 was a disappointing year for Nintendo, it was a great one for Square, the publisher of Chrono Trigger. Debuting at $80 in North America, the memory-heavy game was one of the most expensive Super Nintendo cartridges ever produced. Despite a retail price noticeably higher than other games on the market, Chrono Trigger became a worldwide bestseller. Chrono Trigger’s ultimate origins lie in a project codenamed Maru Island in development for a CD-ROM peripheral that would attach to the Japanese Super Famicom system underneath, alleviating the memory and data storage limits of the system’s game cartridges. Although the CD-ROM add-on never materialized, its co-developer Sony would eventually use it as the basis for their Playstation system, whose entry into the gaming console market would disrupt the traditional Nintendo versus Sega dichotomy of home gaming. The leftovers of Maru Island would be repackaged as two distinct cartridge games with striking visual similarities: Secret of Mana, released in 1993; and Chrono Trigger, released in 1995.

Another stackable Super Famicom add-on was the rather successful Satellaview, a satellite modem launched in 1995 that could receive new game data as it was broadcast. Although the cost of the system and the monthly subscription fees were high, the system was successful—it enjoyed a five-year run before it was discontinued in 2000. The Satellaview is notable for demonstrating an early, if ultimately flawed, model of remotely distributing games.

The Satellaview was never released in North America, and the CD-ROM addition was a future that never came to be either. I can only imagine how ridiculous the angular gray chunk that was my Super Nintendo would look with two big peripheral boxes undergirding the lofty perch of the cartridge slot. The potential existence of this totem of cartridge worship in a world slowly trending toward optical discs strikes me as both foolish and sublimely quaint. It is an image perhaps best illustrated by a Japanese science fiction artist from the 1960s.

I had intended this article to be a way to talk about things that didn’t find a place into my eponymous book on Chrono Trigger. In Japanese, this piece might be called a gaiden—a noncanonical sidestory. But I want to end with another gaiden to the story I’ve been trying to tell here—our collective failure to archive digital pasts.

Who will preserve outmoded technologies for posterity? Attempts to create videos of Virtual Boy gameplay are hampered by the inability to display the system’s 3D technology as it existed—while anaglyphic images can be generated, and then viewed with red/cyan 3D glasses, these would not reflect the games as they were originally experienced. There are also few archives of the Satellaview’s broadcasts, some of which included live narration—whether these exist somewhere in the vaults of Nintendo’s headquarters in Kyoto is a matter of speculation. Concerned gamers, though, have archived many of the games that players downloaded, but this far from a complete snapshot of the compelling Satellaview content that kept Japanese players paying those monthly subscription fees.

It is in another staple of early 1990s futures of the past that I find an idealized, almost-perfect, archive of human achievement—Star Trek: The Next Generation. The all-knowing computer of the starship Enterprise could access and cross-reference data from all manners of polyglot sources, and could announce the compiled results in an even-tempered, clinical voice. But even this near-omnipotent database couldn’t fill in the blanks left by humans of pre-singularity eras. I have trouble accepting a disappointing truth of human progress—there are things that have been forgotten, and they will never be re-remembered.

There is no going back to the mid-twentieth century to snatch up copies of Japanese kids’ magazines for preservation. There is no backwards journey to the 1990s to capture the ephemeral radio narration of Satellaview broadcasts. Our present is as imperfect as our past, and our future will carry this legacy onward.