The King of the Islands of Refreshment

Were the Islands of Refreshment a colonial conquest, the first island micronation—or both? Jed McGowan

An elderly sea elephant lies dozing on a beach. It is a spring morning, and the year is 1812. Unbeknownst to the sea elephant, the patch of sand on which it rests happens to be the most geographically isolated place on planet Earth.

An enormous glistening black shape—an orca whale on the hunt—emerges out of the surf. The orca races up the gentle incline of the beach and scissors the unfortunate pinniped between teeth the size of human hands. But the whale is also being hunted. Watching the scene is a sunburnt man with long scraggly hair, an overhanging brow, and inquisitive eyes. He braces himself, hefts an enormous handmade harpoon, and expertly skewers both orca and sea elephant.

Just another day as the king of the Islands of Refreshment.

The young man is a Yankee sailor from Salem named Jonathan Lambert, and he is the world’s newest and most eccentric head of state. A year earlier, Lambert had formally declared his “absolute possession of the island of Tristan d’Acunha… and the other two, known by the names of Inaccessible and Nightingale Islands, solely for myself and for my heirs for ever.” Lambert reasoned that “as no European, or other power” had ever publicly claimed the islands, they were free for the taking. And renaming: Lambert jettisoned the name Tristan da Cunha, a Portuguese toponym that the main island had borne since the sixteenth century. He rechristened them as the Islands of Refreshment. “Refreshments,” Lambert proclaimed, “may be obtained at my residence,” and he hoped that “all vessels, of whatever description, and belonging to whatever nation, will visit me for that purpose.” The new nation’s naval emblem was a white flag.

Lambert’s statement of possession was self-confident, even lawyerly, grounded on “rational and sure principles”—despite an eccentric mention of “the laws of nations (if any there are)” towards the end. Of course, the truly strange feature of this document was only apparent to those present on the day it was written. Lambert literally represented one quarter of the new nation. The Islands of Refreshment consisted of four people.

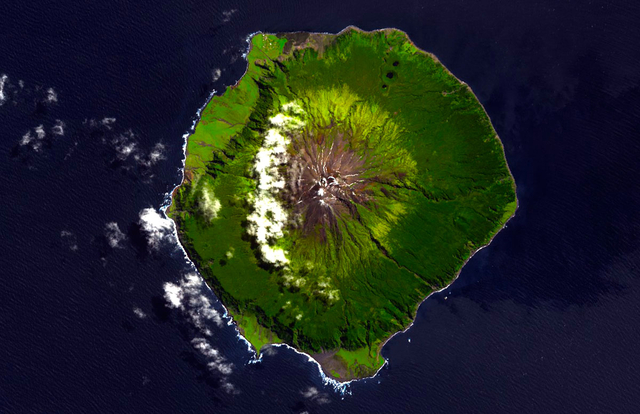

Tristan da Cunha, the sole inhabitable island of the erstwhile Islands of Refreshment, as seen from space. NASA

The Pacific Ocean is our planet’s largest body of water, but the South Atlantic is perhaps Earth’s most desolate expanse of open space. Viewed from satellite orbit, South Atlantic islands like Saint Helena, Ascension, and Tristan da Cunha flicker like miniscule green gems set against a blue void. But they began as flames—jets of molten lava escaping from volcanoes on the sea floor, cooling, then forming outposts of dry land. No humans are indigenous to these islands—indeed, no land mammals of any kind. For millions of years they were the sole domain of birds, of marine mammals, of simple shrubs and grasses. As Homo sapiens made its hungry way out from Africa, moving into Australia, Siberia, Patagonia, Hawaii, these most remote of all islands remained unknown and untouched.

They stayed that way until at least the seventeenth century. Tristan da Cunha, the Portuguese navigator who gave the place its (first) name in 1510, merely spotted it from his ship’s deck, labeled it on a map, and moved on.

Portuguese animal traders as depicted by an anonymous Japanese painter circa 1600. Wikimedia Commons

Lambert believed himself to be the first human to set foot on the island, but this claim is thrown into doubt by his off-handed mention of the presence of wild boars. Portuguese and Spanish sailors were famous for “seeding” desert islands with goats and pigs stored in ship holds. Later expeditions would then return to these islands years or decades later to find thriving colonies of feral (and tasty) herds.

In other words, if wild boars or goats happen to be nosing around on your desert island, you can bet that an early modern Iberian sailor got there first. Indeed, one such island, Exuma in the Bahamas, is still home to a large colony of feral-but-friendly swimming porcines who inhabit a place called “Pig Beach.”

But even if Lambert and his three companions weren’t the definitive discoverers of the island, they were almost certainly the first humans to permanently settle on it. Or at least to make the attempt.

Life on the Islands of Refreshment, it turned out, was almost impossibly miserable.

For a year after his crowning as king, Lambert threw all of his energies into developing the island’s fledgling economy. He and his three subjects (a friend named Andrew Millett, a man known as Thomas Currie or Tomasso Curri, and an unnamed “apprentice boy”) tended to a small flock of geese, ten breeding pairs of chickens, a few dozen cattle and a herd of wild boars. They went scouting with the island’s unofficial fifth subject, Lambert’s dog, and nurtured a garden of cabbage, beets, carrots, parsnips, and lettuce. But as Lambert admitted in his final letter from the island (which was sent to his friend, the Indian-born army officer John Briggs, and later republished in the Edinburgh Magazine), “our situation, like all new settlers, has not been very comfortable.”

That was a massive understatement. Several pages into his letter, which dwells on the fresh air and natural abundance of the region, Lambert let slip a revealing fact: the residents of the Islands of Refreshment, man and beast, actually subsisted almost entirely on elephant seals. “We have killed about 60 since we landed,” he reported, “and I suppose we shall kill about two a-week through the year.” Stop and consider this for a moment: southern elephant seals max out at approximately 6,600 pounds. In other words, the four humans and several dozen animals of the Islands of Refreshment went through around 8,000 to 10,000 pounds of oil-laden elephant seal meat and blubber per week. Which, though presumably sustaining, doesn’t sound particularly refreshing.

Lambert consoled himself with the (never realized) prospect of making a healthy living by selling the elephant seal’s oil to traveling mariners. But until then, the king’s life seems mainly to have consisted of elephant seal hunting interspersed with the tedium of growing, cooking, and eating bland root vegetables. “Turnips have been bread to us,” is another buried lede in Lambert’s final letter. Lambert even apparently tried to domesticate his local sea elephant herd, describing his “two ponds, where the sea elephants abound; here I have 8 sows, and 4 boars quite tame; all of which, save 5, we have caught on the island.”

King Lambert never had a chance to see his plans reach fruition: his reign ended after a year. Lambert and two of his subjects, fully three quarters of the island’s population, drowned in a fishing expedition in May of 1812.

But Thomas Currie survived, and he lived to see the modern history of the islands take shape.

Even today, the Tristaners (as they’re called) carry on a hardscrabble existence, eking out a living in the volcanic soil by growing potatoes and harvesting lobster for sale to Japan.

“The Tristan islander lives with his back to the mountain and his face to the sea,” was the Royal Navy officer Derick Booy’s impression in 1942. Booy had been sent to the islands at the height of World War Two in order to set up a secret U-boat monitoring station. But he became preoccupied by the strange and tight-knit society he found there. By the 1940s, the island was home to 200 people who shared only seven family names in total: Glass, Swain, Green, Rogers, Hagan, Repetto, and Lavarello. Today, these seven families are still the sole residents of the islands, and the population is only slightly larger, hovering at around 270.

But when Lambert died, this relatively populous future was still a century from fruition. From being islands of refreshment and hospitality, Tristan da Cunha and the other South Atlantic islands would become places of solitude in the decades following Lambert’s one-year reign as king.

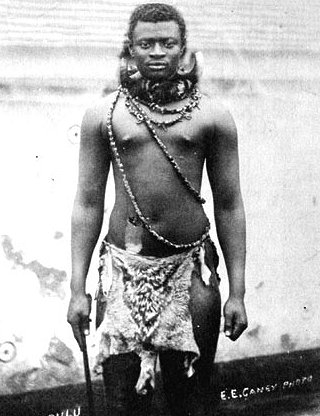

The island’s closest neighbor, St. Helena, emerged as a kind of exotic imperial prison: it was there that the British confined Napoleon following his defeat at Waterloo. Seventy years later, a second defeated military leader would be exiled at St. Helena: Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, the King of the Zulu. Islands like St. Helena and Tristan da Cunha ceased to tantalize adventurers and sailors with the promise of a life of Robinson Crusoe-like self-reliance. They became way stations in a vast system of global empire, staffed and maintained like fortresses, and administered by bureaucrats thousands of miles away.

In the great games of nineteenth-century imperial rivalry, it seemed impossible that such tiny outposts could ever be more than places to restock supplies or deposit the occasional prisoner. But in the twenty-first century, such tiny, remote islands have taken on a entirely different function.

Starting in 1967, when a group of British oddballs founded Sealand on an abandoned World War Two platform off the coast of England, micronations have been enjoying a renaissance. One of the pioneers of the movement was none other than Ernest Hemingway’s brother Leicester, who constructed a small platform off the coast of Jamaica, dubbed it New Atlantis, and declared himself its ruler. The island’s constitution was simply the U.S. Constitution with the words “United States” replaced by “New Atlantis.”

These early micronations attempted to make a living by selling collectible coins and stamps—a tactic employed by the current residents of Tristan da Cunha as well. One resident wrote in 2009 that:

We do get visitors here on Tristan—up to 130 a year on “regular” passenger vessels plus several hundred more via the handful of cruise ships which call. Our main income is derived from lobster fishing, although we also earn revenue from the sale of commemorative stamps and coins.

A thirty-five dollar coin from the short-lived Republic of Minerva, created on a coral reef in the South Pacific by a Los Vegas real estate millionaire in January of 1972 and invaded by the Tongan navy in September 1972. Wikimedia Commons

The histories of micronations are often histories of personal eccentricity. Michael Oliver, a Lithuanian immigrant turned Las Vegas millionaire, devoted a fortune to sustaining the short-lived Republic of Minerva (1971-1972) in the South Pacific, only to see it collapse following an invasion by the Republic of Togo. Yet Oliver persisted, founding a libertarian group called the New Hebrides Autonomy Movement in Vanuata (which has since slapped him with a lifelong ban). Purely whimsical micronations abound, from the Belgian Niels Vermeersch’s Grand Duchy of Flandrensis, which has claimed five islands off the coast of Antarctica, to the Republic of Kugelmugel, which occupied an orb-shaped house in 1980s Vienna.

Other plans have been more serious, for better but usually for worse. The Dominion of Melchizedek is perhaps the shadiest micronation of all, created almost entirely to facilitate international crime. It lays claim to a handful of uninhabited islands and lands in Antarctica, and can be traced back to a father and son duo, the Pedleys, who began operating it in the mid-1980s. The Dominion has been accused of selling fraudulent travel documents to hundreds of Chinese, Filipino, and Bangladeshi immigrants. It is recognized by only one country, the Central African Republic, and its current president is a mysterious Filipino-American businesswoman named Pearlasia Gamboa. Things get even weirder from there: the Washington Post described the micronation’s history as a “walk down a bizarre labyrinth that includes a home-brew religion.”

Micronations also loom large in the writings of near future sci-fi novelists like Neil Stephenson and William Gibson. In his cyberpunk classic Neuromancer, Gibson described independent orbital platforms used as tax havens, casinos, and even Rastafari outposts, while Stephenson envisioned the rise of independent nations functioning as “data havens” for encrypted web traffic. Recent investments by tech billionaires like Peter Thiel in an organization known as the Seasteading Institute hint that this latter prediction, at least, is on its way to becoming a reality.

Yet while they might look forward to these twenty-first century futures, the present-day inheritors of the Islands of Refreshment also face the past. Simon Winchester, who wrote about the island for his book Outposts, observed that “the older islanders incorporate nineteenth-century ‘thees’ and ‘thous’ into their speech.” History is still ever-present in the islands, for the simple reason that there isn’t much to go around. The documented human history of the place begins with Lambert and ends only two hundred years later in the present day.

The events that took place in between have taken on a towering importance in local lore.

The first edition cover of Derrick Booy’s Rock of Exile: A Narrative of Tristan da Cunha (London, 1957).

Winchester became especially interested in the Royal Navy officer Booy’s 1942 visit and the book he wrote about it, Rock of Exile. Booy fell in love with a local girl named Emily who he remembered even decades later with an almost suffocating vividness:

The night air was an enveloping golden presence as we stood at the break in the wall. I was conscious of bare, rounded arms and the fragrance of thickly clustered hair. The lingering day was full of noises. As the sky darkened to a deep, umbrageous blue, speckled with starlight, and the village was swallowed by darkness at the foot of the mountain, from somewhere in that blackness came the throaty plaint of an old sheep, like a voice from the mountain… the girl waited only a few minutes before her full lips breathed “Goodnight,” and she slipped toward the house.

Winchester performed a bit of sleuthing during his visit, tracing the aftermath of the officer Booy’s love affair. He eventually found the house where Emily lived some forty years later, now married to a local Tristaner who Winchester asked about his past. But on an island like this, even a broken-off love affair with a military man—surely one of the most common personal tales of the World War Two era—took on a powerful local significance. It became part of the island’s scanty past, and with it, part of its future. It’s a lesson about history and its futures that nation-builders from Lambert to the contemporary vanguard of Libertarian micronations would do well to keep in mind.

“Remember,” the man told Winchester. “Whatever you write will last for years; we back on the island will pore over it and analyze it a thousand times. Be careful what you write—for our own sakes.”