Space Cadets and Rat Utopias

The real-life rats of NIMH. Space Cadet Thermos, 1954, National Museum of American History, 2003.3070.18.02.

In 1956, researchers Leonard J. Duhl and John B. Calhoun organized a meeting to discuss space. Not outer space, as the year might suggest, but earth space. Duhl and Calhoun, both posted at the National Institute of Mental Health, wanted to know whether the arrangement of objects in the physical environment affected human well-being. Their choice of meeting title was not subtle; they called it “The Conference on Social and Physical Environmental Variables as Determinants of Mental Health.” But the seventeen invited participants—psychologists, sociologists, ecologists, and one “social physicist”—preferred to call themselves “The Space Cadets.”

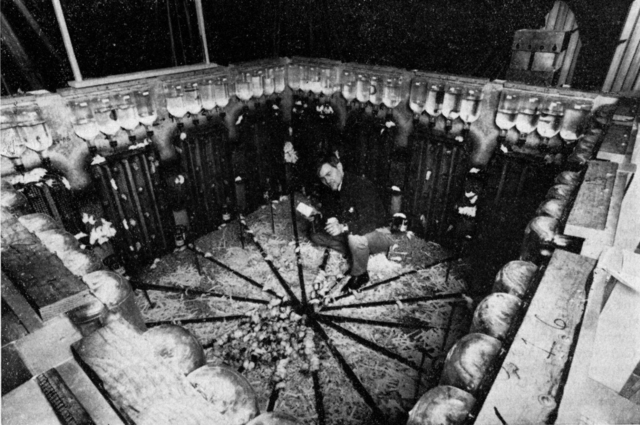

At the NIMH, Duhl specialized in mental health programming. He was a “small, tweedy, quiet-spoken” man who had volunteered for the Public Health Service during the Korean War before finishing his psychiatric training at the Menninger Clinic, in Topeka, Kansas. Calhoun, meanwhile, trained as a zoologist, was studying the social behavior of rats. He began this work in 1947, when a neighbor in Towson, Maryland, agreed to let him build a rodent enclosure behind his house. Calhoun designed experiments to study how population density affected social behavior. The experimental rats enjoyed a world free of predators, disease, and hunger. Their only restriction was space. He called the quarter-acre rat enclosure a “rat city.” He called the room-sized enclosure he would later construct at the NIMH a “rodent universe,” a “mouse paradise,” a “rat utopia.”

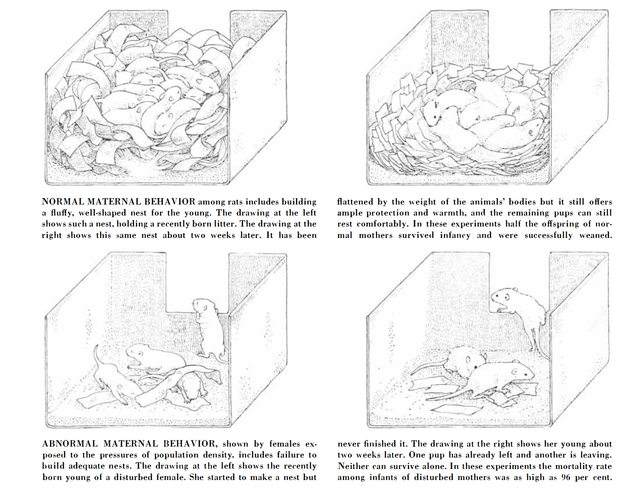

But the trajectory of rat utopia soon sobered Calhoun. The eager rodents did not seem capable of regulating their population size in the long-term. As they reproduced and the pens overflowed, Calhoun noted that male rates became aggressive, moving in gangs and attacking females and young. Some became exclusively homosexual. Female rats, meanwhile, abandoned their infants. The crowded mice had lost the ability to coexist. One of Calhoun’s assistants renamed the “rat utopia” “rodent hell.”

A figure from Calhoun’s 1962 paper, illustrating the behavior of “normal” and “abnormal” mother mice. Image from John B. Calhoun, “Population Density and Social Pathology,” Scientific American 306 (1962): 139-148.

Calhoun saw in his rats the decline of future society, evidence that inner city crowding led to rioting, crime, malaise, and political radicalism: the obsessions of postwar American academics. He wrote up his results in a Scientific American article that he titled “Population Density and Social Pathology.” The article became one of the most widely-cited papers in psychology. Like Pavlov’s dogs and Skinner’s pigeons, Calhoun’s rats became exemplars for human behavior. His experiments suggested a density beyond which rat society disintegrated, and—to Calhoun and his colleagues, at least—the parallels with human society were clear.

Time might have obscured the tale of Calhoun’s rats, if not for publication of the 1971 children’s book, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH. The book tells the story of a widowed field mouse, Mrs. Frisby, who asks a group of former laboratory rats to help her rescue her home from the farmer’s plow. (It also details the history of the rats’ escape from the laboratory and development of a technological society.)

I first encountered the stenotype transcripts of “The Space Cadets” while at the University of Georgia’s Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library. I was there researching ecologist Eugene Odum, one of the popularizers of ecosystem theory, whose archives have yet to be fully processed. I had already sifted through troves of odd objects: ashed birds, skulls, Kodachromes, coral from the Pacific Proving Grounds, Odum’s pants (the potential radioactivity of the coral from Bikini Atoll concerned me until I found, twelve boxes later, a form stating that the samples had been deemed safe to handle in 2007).

Overwhelmed, I decided to spend an afternoon looking at the Ecological Society of America’s archives, which are also housed at Hargrett Library. It was in this collection that I stumbled upon a letter from Edward Deevey, a former ESA president, to, well, to me. It read:

The file I’m sending to the archives has been sitting in a storeroom for the 14 years I’ve been at Florida. It contains a lot of dross, because Duhl send us xeroxes of everything he read, but I believe the file of stenotypic transcripts is complete, and somehow, someone has to pay attention to the role of social science in forming the research program of human ecology. Of course this panel was only one of the more visible of many “invisible colleges” that contributed to the subject, but if it’s only worth a footnote in a history of 20th-century ecology, it’s at least an interesting footnote.

For the future historian of ecology, these activities cover pretty well the state of the science in the 60’s, and indicate the directions in which a number of leading ecologists were trying to push it.

The note threw me. Edward Deevey died in 1988, but here he was, speaking to me. And here I was, making assumptions about him and his colleagues, what motivated them, how they spent their days.

Ashes of Parula Warblers in a fruitcake box, one of many treasures in the Eugene P. Odum papers at the Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Courtesy of Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library / University of Georgia Libraries. Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, MS3257, series 1, carton 149.

The Space Cadets met twice a year from 1954 to 1966. From seventeen founding members, the group eventually grew to two hundred panelists. Edward Deevey recounted: “We met at [the National Institute of Health], or in some hotel, usually the Dupont Plaza; entertainment at buffet suppers was fabulous, but the conversation was more so.” Other long-term members were Duhl, Calhoun, the psychiatrist Erich Lindemann, the urban economist Harvey Perloff, the sociologist Herbert Gans, the philosopher Scott Buchanan, the biomathematican Nicolas Rashevsky, the physicist John Q. Stewart, and the urban planner Richard Myer.

At first, conversation centered on two questions: What was mental health? And what was the place of federal planning in mental health? Or, more specifically: Were insights from the mental health of individuals applicable to the collective? And was planning compatible with democracy? At stake in these conversations was the question of whether social scientists could contribute to building the future world. If recent advances in psychology could be generalized to the collective, then the Space s could collaborate to build better cities.

But not all of the Space Cadets agreed that social behavior could be modeled. At the October 22 meeting, in 1959, John Seeley of the Alcoholism Research Foundation and Thomas Gladwin of the NIMH sparked a debate on the appropriate use of scientific models in studying “social adaptation”:

DR. SEELEY:

[…] this whole dramatic operation takes place inside History, over which, in its large movement, we have no control, which is a single, unique, unreproducible act, utterly unlike the experimental model. […] The closer we approach to the model of the machine or the biological machine, the more we must lead ourselves astray and the more we must turn our attention away from that which we have come here precisely to do, namely to insure that human life will be different because of our being here from what it might otherwise have been, by deliberation, by choice, by something that is as far from adaptation as anything I can imagine.

DR. DUHL:

You have silenced the group.

DR. SEELEY:

Only for a moment.

DR. GLADWIN:

I wonder, Jack, why you are so concerned. It appears to me that every attempt to approach society, whether scientifically or otherwise, involves the selection of a limited number of dimensions, a restriction in the total complex perspective. If you are Karl Marx you look at it in terms of economics; if you are Freud you look at it in terms of conflict and resolution of conflict; others do it in still different ways. Whether we try to set up an organic or a mechanical model, there will be those who feel that it is all-inclusive, but these are not usually the people whose opinions we would respect anyway. This is just one way of working toward a series of successively closer approximations, through the isolation of relevant variables and modes of description, which will enhance our understanding of our society. As I see it, it doesn’t restrict our range of choice. It simply gives us another mirror in which to see society reflected, another filter which filters out some things and lets other useful things come through.

Students in the Department of Geography and Community Planning at Appalachian State University in 1977. University Archives, Appalachian State University, General Picture Files, 2004.040, Box 10, Geography and Planning, C14.2.2.4.

As the years passed, new concerns crept into the Space Cadets’ conversations: nuclear annihilation, birth control, racial integration, communism, computers, the “problem of ulcers and coronaries in terms of social climbing in suburbia.” At one session, the group discussed The Fund for the Republic’s Center for the Study of Democratic Institutions’ 1960 report, Community of Fear, which imagined a future cave-dwelling society living in cities dug underground to escape the hazards of nuclear war. The Space Cadets wondered: Would there still be social anxiety underground?

Leisure time was another sticking point. As Dr. Gans proclaimed in a 1961 meeting, “a generation ago, boating and golf were upper-income group sports; today, almost everyone of middle income who is not afraid of the water or too lazy to walk the greens can participate in both.” Summer theatre, art movies, foreign travel, do-it-yourself activities, photography and painting, television. A number of critics argued that “citizens” (read: upper middle class white families) would soon be unable to psychologically cope with further increases in leisure time. The Space Cadets discussed “weekend neurosis,” a condition that existed mostly among professional people “for whom work is so pressing or exciting that all other forms of activity pall.”

DR. FEISS:

If we figure an 8-hour day, with five workdays, roughly 8 hours of sleep—some of us don’t get it—we have another 8 hours which is also undesignated, which, theoretically, is used in family activity or otherwise, or a total of another 153 days. The two together mean 157 days of the year, out of 365, in which we have leisure time or unassigned time. That is a devil of a lot of time.

Dr. Gans’s research suggested that “the pleasures of being outdoors are as satisfying in a small backyard as they are in the majestic environment of a National Park landscape.” Perhaps the urban individual was subject to a “sensory overload” to which he or she was not adapted.

DR. SEELEY:

I think this presses differentially on the man and woman. I think the man in many suburbs would say “I see enough diverse kinds of people during the day” (and this is probably true) “and when I come home at night I want to be among my own.” The isolated woman, in some suburbs at least, says “I never see anybody different from myself. Let me go out—let me go to the club—let me play golf—let me play tennis,” and a number of other things.

Calhoun, for one, believed there was a natural limit to the number of social interactions an individual rat—or human—could psychologically handle, so that large groups over a certain size—twelve, to be exact—bred discontent. Put more than twelve in a space and unwanted interaction would lead to hostility and withdrawal, and ultimately, social breakdown. A fan of H. G. Wells and George Orwell, Calhoun put stock in the alternative futures those authors imagined.

But the bomb loomed large.

MR. POSTON:

All this concern about leisure time always bothers me because I feel that we are living in an age when 25 years from now our civilization may not exist. I think that we are currently engaged in a world struggle for survival, and I don’t think there is much time. So that when people talk about the Americans lounging around in parks and worrying about whether or not there are enough swimming pools, that sort of thing concerns me.

John B. Calhoun in the rat universe, 1970. John B. Calhoun, “Death Squared: The Explosive Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 66 (1973): 80-88.

Today the Space Cadets are remarkable for exploring the confluences of psychology, ecology, and urban planning. Although psychology and ecology still occasionally interface (think Last Child in the Woods or “biophilia”), sociobiology peaked in the 1970s, and ecologists rarely meet with their urban planning equivalents, landscape architects. Ecology, a field founded to resist disciplinary borders, is now a well-defined discipline that deals with rats but not humans.

Human population growth, it seems, is the only interest of the Space Cadets that has remained central to ecology and conservation biology. Many believe that disaster looms in the future, that humans will overflow their earth as Calhoun’s rats overflowed their pens. Others believe in the power of technology to overcome famine and fear, a technological utopia.

And so it was no surprise that a September 2013 New York Times Op-Ed article entitled “Overpopulation is Not the Problem,” caused a kerfuffle. Erle Ellis, an ecologist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, wrote:

Many scientists believe that by transforming the earth’s natural landscapes, we are undermining the very life support systems that sustain us. Like bacteria in a petri dish, our exploding numbers are reaching the limits of a finite planet, with dire consequences. Disaster looms as humans exceed the earth’s natural carrying capacity. Clearly, this could not be sustainable.

But Ellis went on:

This is nonsense. […] The conditions that sustain humanity are not natural and never have been. Since prehistory, human populations have used technologies and engineered ecosystems to sustain populations well beyond the capabilities of unaltered “natural” ecosystems.

Joel Cohen, Daniel Schrag, and William Clark, professors at Columbia University and Harvard University, respectively, retorted:

It is not possible to predict precisely what some human choices may lead to, or whether some future environmental changes may be beyond human control. It is clear, however, that every additional billion people constrain further the choices available for life on earth, human and otherwise.

Such debate nests within a larger contemporary debate over “the Anthropocene.” The magnitude of global change— an umbrella term that includes rising tropospheric CO2 concentrations, increasing UV-B irradiation, species invasion, eutrophication, radionuclides in oceans, and biodiversity loss—has prompted some ecologists to use the term “Anthropocene” when referring to the present geological age. (The International Union of Geological Sciences continues to use the term Holocene.)

Few scientists contest the magnitude of human impacts on the Earth. Humans consume about one-third of all solar energy converted to plant matter, and their actions directly impact 75 percent of the terrestrial world—or, if we take climate change into account, the entire world. But many contest what it means to adopt the term Anthropocene. Rather than the “cheery” Anthropocene, E.O. Wilson prefers to call Earth’s new era of history the Eremocene: the Age of Loneliness. Elsewhere, Erle Ellis has called the Anthropocene “an opportunity we should embrace.”

Fifty years ago, the Space Cadets, too, were divided over whether the future was dismal or bright. In 1948, two books were published that inspired a “neo-Malthusian” debate on population and the environment: Fairfield Osborn’s Our Plundered Planet and William Vogt’s Road to Survival. While attending college in the early 1950s, Paul R. Ehrlich heard Vogt lecture. The lecture resonated, and Ehrlich went on to publish The Population Bomb in 1968. In it Ehrlich warned of mass famine and social upheaval in the 1970s and 1980s due to overpopulation. The Population Bomb went on to sell two million copies within its first two years and go through twelve re-printings, selling more copies than Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962).

Calhoun and some of his fellow Space Cadets rejected Ehrlich’s “dismal theorem”—the idea that each additional human would have a negative impact on the environment. While the media portrayed the future as one of malnutrition, disease, and misery, the Space Cadets asked how to control human behavior while not restricting an individual’s freedom of action. The way to avoid the future necessity of individual psychotherapy, they contended, was to manipulate the present environment. And to do this they needed first to understand the relationship between space and behavior. Different arrangements of yards, housing units, streets, and commercial centers could, perhaps, ward off disaster.

In his early experiments, Calhoun believed he had observed innovation in rat society. When building a new burrow, some rats did not simply dig out the dirt as they went, “as any normal rat would do”; rather they packed it into a large ball that they then rolled out. This innovation had come not from the socially dominant individuals, but from a disorganized and withdrawn group of subordinates. Inspired by this example, Calhoun attempted to design rodent universes that would produce “creative deviants.”

Calhoun also believed that future technologies would change the nature of the environments in which social interactions occurred. He predicted that a “communication-electronic revolution” would occur in 1988. As the availability of physical space declined, human society would extend into “conceptual space” to better use natural resources while ensuring that each individual maintained a limited number of social interactions.

That part sounds about right.

I returned to the Odum papers grateful for the glimpse that Deevey had given me into the concerns and ambitions of a generation of social scientists. It had kept me away from Facebook, that leisure destination of the post-communication-electronic-revolution workday. As of 2010, there were thirty times more farmers on the Facebook game FarmVille than there are in the United States. In the spirit of the Space Cadets, we might also ask how many acres those FarmVille farms comprise in “conceptual space.”

In his discussions with the Space Cadets, Calhoun struggled with the limitations of models. Could rat behavior stand in for human behavior? Was an overflowing pen at all like a city? Was behavior determined by population size or by individuals? Such questions were unresolvable. But it was important to ask them.

Like the Space Cadets, today’s Anthropoceners are attempting to model the present world with an eye towards the future world. Today’s Anthropocene discourse constitutes a teleological argument—it posits that past human action has set us on an inevitable trajectory that ends with the Anthropocene. (If this last point is unclear, ask: When will the Anthropocene end?)

Anthropoceners are interested in the universal, not the particular. They seek global patterns. And so they aggregate the impacts of human lives. But while generalizations are often generative, patterns alluring, the Anthropocene model is blind to the distribution of power. It asks what—what are the consequences of human action—and not who—who is acting, who is responsible, who is suffering. The Space Cadets modeled the disenfranchised with rats. Who are the Anthropoceners modeling? And for whom is their future world?