I Sing the Body Atomic: Nuclear Transformation in the Marvel Universe

How the atom bomb shaped the Silver Age of comics. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, The Incredible Hulk, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 1, May 1962.

In the 1960s, Marvel Comics went atomic. The mystically inclined or serum-imbued superheroes from earlier decades gave way to scientific heroes who conquered the atom—or were conquered by it. At the core of these books were nuclear metamorphoses that turned ordinary people into weaponized paragons of the Atomic Age.

The Marvel Comics universe has, since its 1930s beginning as Timely Comics, hosted a diverse array of heroes, villains, anti-heroes, conflicted bad guys, ordinary folks, and morally ambiguous beings. Between 1961 and 1964, Marvel entered its most iconic era, debuting The Fantastic Four, Daredevil, The Avengers, The X-Men, Iron Man, Ant-Man, The Incredible Hulk, among other notables. These atomic heroes soon became as synonymous with Marvel Comics as Captain America, Marvel’s flagship hero of the 1940s.

The early heroes of the Marvel label encapsulated the concerns and scientific progress of the time. Captain America emerged at a time when modern physicians were perfecting new vaccines for debilitating diseases. So if an injectable serum could prevent disease, it could also turn a 98-pound weakling into a peak-human marvel. Marvel debuted few—if any—heroes in the 1950s. But in the post-Comic Code era (1954 onwards), their focus shifted to sci-fi and monster comics which would eventually metamorphose into a second superhero era.

The Marvel of the 1960s harnessed contemporary science headlines to give their superheroes new ways to gain power. Rather than using serums and potions to imbue individuals with superpowers, Marvel bonded its superheroes to the atom. Superheroes became living atomic weapons. Yet in the process, they also became vessels for atomic fears and the bodily horrors of mutation the atom could cause. The same atomic sources that birthed their superpowers also negatively impacted their life.

The Age of the Atomic Superhero started with a rogue scientist who rocketed his fiancé, her brother, and a pilot into near Earth orbit, catapulting them into the space race “to beat the Russians.” And thus were born the Fantastic Four. As Rafael York puts it in his study of Cold War comics, “In the case of The Fantastic Four, it is not the mystery of nuclear power that creates trepidation, but the effects of cosmic rays on humans, but in a fundamental sense the source of the fear remains the same. It is the fear that scientists will be unable to control the forces with which they tamper.”

Pilot Benjamin Grimm transforms into The Thing for the first time after his exposure to cosmic radiation. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Fantastic Four, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 1, November 1961.

With nuclear weaponry came nuclear paranoia. In the same year as the first issue of Fantastic Four, the world came precariously close to nuclear war with the Bay of Pigs incident. While science was making leaps and bounds—the space race was on its way, nuclear weapons begat nuclear power, and vacuum tubes were replaced with transistors—the idealism of the 1950s was crumbling. Technology was becoming a race, a space race, an arms race, a race to the technological top.

By rocketing his friends into space, Reed Richards, a doctor of some unspecified science affiliated with an unnamed university, was flinging himself into the nascent space race. But the mission lacked the sort of precautions necessary to survive in deep space. While cosmic rays may have been a comic book means to an end, they also represented an unknown. In 1957, we were only beginning to understand space. It remained a mysterious void. By thrusting himself into the void, Richards and crew opened themselves up to what this unknown environment could unleash on them.

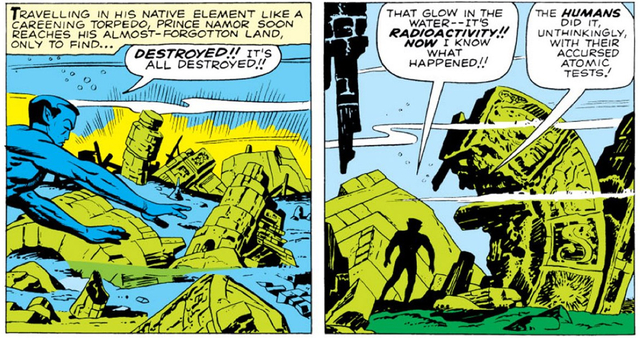

In Fantastic Four #4, the Fantastic Four encounter Namor, the Sub-Mariner, whose home of Atlantis had been destroyed by nuclear catastrophe. Vowing revenge, the Sub-Mariner summons a leviathan, Giganto, to punish humanity for their carelessness with their nuclear projects. As York summarizes the episode:

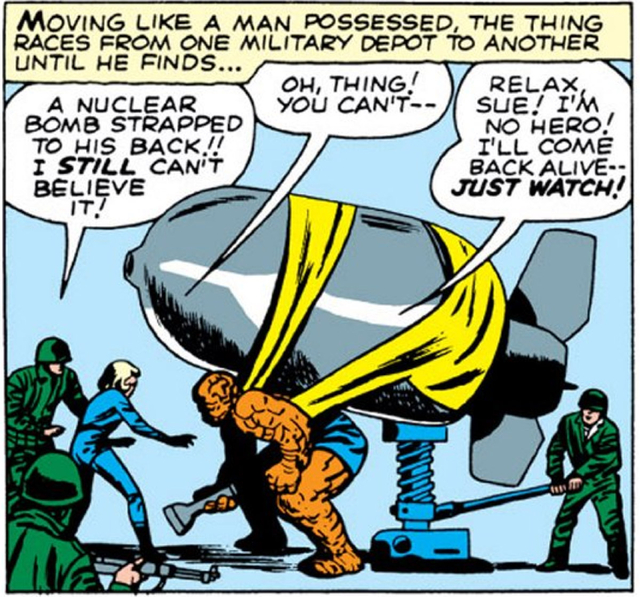

When the Sub-Mariner unleashes his atomic bomb on New York, it is only fitting that The Fantastic Four should retaliate with its own nuclear bomb. The Thing only acquires the necessary ordnance after racing “from one military depot to another,” indicating that the United States government is not only aware of the intended use of the bomb, but that it is complicit in the bomb’s detonation. The Thing’s bomb proves to be more powerful than Giganto, and in this story, the US emerges victorious in the arms race.

It’s perhaps ironic that The Thing employs a nuclear weapon to destroy a creature summoned to punish acts of nuclear aggression.

Namor, Marvel’s first superpowered character, returns to Atlantis to discover it destroyed by atomic weapons. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Fantastic Four, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 4, May 1962.

The Thing straps an atomic bomb to his back to destroy a leviathan summoned by an angry Namor. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Fantastic Four, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 4, May 1962.

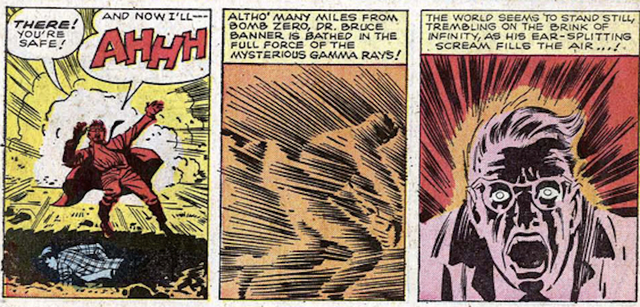

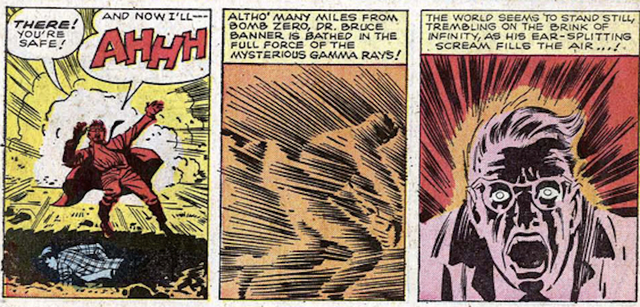

In May, 1962, Stan Lee grabbed the headlines again, introducing a new atomic quasi-hero, the Incredible Hulk. In the first issue, a scientist working on the Gamma Bomb named Bruce Banner absorbs radiation owing to sabotage at the hands of a communist agent. Banner absorbs the radiation, and unleashes his inner Id: a grey brute called The Hulk. In Lee’s atomic age vision, Dr. Jekyll meets Mr. Hyde through gamma radiation.

Bruce Banner absorbs the payload of a Gamma Bomb and somehow escapes being instantly vaporized. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. The Incredible Hulk, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 1, May 1962.

The Hulk’s skin would later turn green, but it didn’t repair his tortured soul. More than most heroes, the Hulk agonized over the consequences of his nuclear nature. Not only was his body transformed continuously into the inner horrors of Bruce Banner, but he would later lose his wife (for a period of time at least, this being Marvel) to radiation poisoning.

As with Reed Richards, Bruce Banner gained his powers by becoming the victim of his own research. While Richards and the other members of the Fantastic Four exposed themselves to radiation through pure hubris, Bruce Banner knew the dangers of the gamma bomb. As the Hulk, Banner took on the characteristics of his own weapon and unleashed his temperamental Id.

By writer Stan Lee’s own admission, the comic book was a propaganda vehicle. Looking back at the previous decade in 1975, Lee enjoined his readers to remember that “most of us genuinely felt that the conflict in that tortured land [Vietnam] really was a simple matter of good versus evil”:

that the American military action against the Viet Cong was tantamount to St. George’s battle against the dragon. Since that time, of course, we’ve all grown up a bit, we’ve realized that life isn’t quite so simple, and we’ve been trying to extricate ourselves from the tragic entanglement of Indochina.

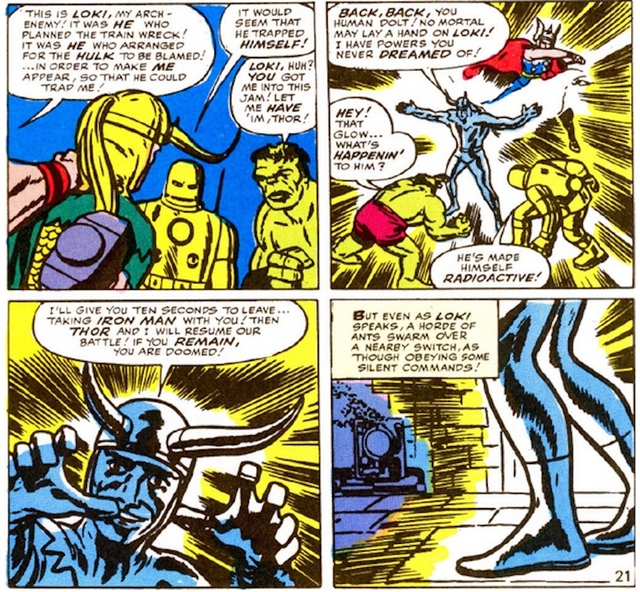

Lee also had in mind a Marvel hero whose origin story begins in Vietnam: Iron Man, née Tony Stark. Ant-Man, Wasp, The Hulk and Iron Man would eventually accidentally congeal into a heroic team known as The Avengers, alongside the distinctly non-atomic Norse thunder god Thor. The team of weapons came together in Avengers #1, quite accidentally. The villain, Loki, even weaponizes himself:

“I have powers you never dreamed of!” Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. The Avengers, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 1, August 1963.

To vanquish the villain, The Avengers seal Loki away in a lead vault to expend the energy. The team debate depositing him in an ocean vault along with other lead-sealed nuclear waste—a solution that sounds fantastical now but was an actual practice. Ultimately they resolve to free him once his “fuel” is spent. Loki, in order to take on the Avengers, must become atomic himself. And while The Hulk, Iron Man, Thor, Ant-Man and Wasp are allowed to continue making displays of atomic force, they must contain and dispose of the enemy before he wields the power of the atom.

It was the nuclear arms race, redux: we need the top of the line weapons in order to subvert whatever weapons the enemy may have.

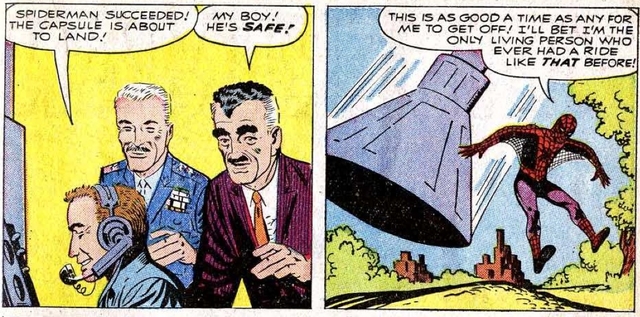

Perhaps the most iconic Atomic Age hero of all is Spider Man, who first appeared in Amazing Fantasy. For all his reluctance to delve into heroics, Peter Parker, as Spider Man, became and continues to be one of Marvel’s most enduring protagonists. Amazing Fantasy was cancelled that very issue, but Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s creation would be back in Amazing Spider-Man #1. The issue introduced newspaper publisher J. Jonah Jameson, Spider-Man’s nemesis and Peter Parker’s boss. After saving Jameson’s astronaut son, who was just “mak(ing) his country proud,” the Daily Bugle lambasts him as a menace, despite his heroic effort.

Spider-Man enters the Space Age on his second adventure. Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Amazing Spider-Man, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 1, March 1963.

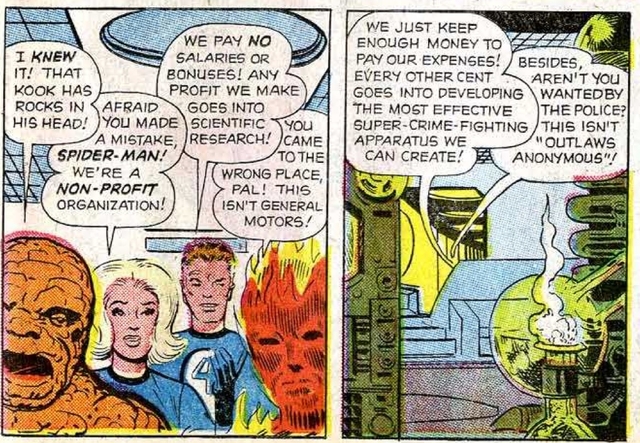

Spider-Man gains his powers from a radioactive spider, and other atomic MacGuffins propel the plot as well. In Amazing Spider-Man #1 Spider-Man tussles with the villainous Chameleon, a freelance mercenary gathering atomic secrets for any Iron Curtain country willing to pay the right price. But Spider-Man manages to best the villain, but not before nearly being arrested himself. The end of the issue has Parker running away, wishing he’d never gained his powers.

Peter Parker, as a teenager thrust into the midst of the superhuman arms race, emerges as a different sort of hero than the Fantastic Four, the Hulk or Iron Man. Peter Parker wasn’t the victim of hubris or accident or invention of the characters’ own design. He was a witness to the scientific progress of the era, and was the innocent bystander to it all—a victim of ambient radiation and transformation.

Spider-Man finds out that being a member of the Fantastic Four is basically an unpaid internship. Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Amazing Spider-Man, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 1, March 1963.

Parker embodied the dark side of science. Even in his second adventure, he’s trying to prevent a catastrophe in the space race. Like the Hulk, he would become an outcast, never fully fitting into the role of hero in the public eye in the way the citizen scientist Fantastic Four or peacekeeping soldier Avengers could. Peter Parker was what could happen to the common man in the face of the scientific era.

The X-Men were the so-called “Children of the Atom,” the title lifted from a Wilmar Shiras novel of the same name. The X-Men were bodily transformation—and occasionally body revulsion—personified. They were teenagers who, at the onset of puberty, exhibited a mutated gene on the 23rd chromosome that caused strange powers to manifest. The X-Men were living weapons, persecuted by the world. Or as they put it, “Hated and feared by a world they were sworn to protect.”

Two X-Men characters in particular stand out as “Children of the Atom,” as their mutations came from a parent’s direct exposure to radiation.

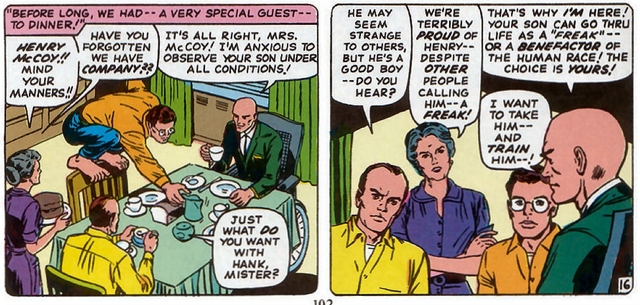

The mutation of Hank McCoy—better known as the Beast—resulted from his nuclear engineer father’s exposure to radioactive elements. The transformations of McCoy offered a window into 1960s America’s horror of the effects of radiation. His hands and feet are giant sized, his posture not unlike an ape. In later iterations, he sprouted fur.

Charles Xavier meets the McCoys, including their big-limbed son. Unlike his teammate Iceman, Hank McCoy received unconditional support from his parents. Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. X-Men, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 15, Sept 1963.

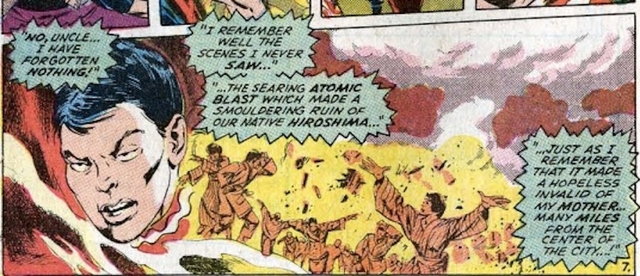

The second atomic X-Man was the Japanese superhero, Sunfire, née Shiro Yoshida, introduced in 1970’s X-Men #64. His powers came from a parent’s direct exposure to radioactivity. Shiro Yoshida blasted beams of plasma, as if he were the embodiment of hydrogen fission, with the temperament to match. Unlike Beast, that exposure wasn’t from a power plant, but from his mother’s exposure to the horrors at Hiroshima. His mother later died of radiation poisoning. For Marvel, this was a rare nod to real-world consequences of the Atomic Age.

Coming after Stan Lee’s tenure on X-Men, Yoshida was a realistic response to nuclear aggression. He was angry, having lost his family to atomic violence. And like Peter Parker, he was unwittingly the recipient of someone else’s payload, given powers he never asked for in the fall out of the act of nuclear warfare. In this sense, Yoshida was the antithesis of Marvel heroes that had come before. He was cursed, not blessed, by the atom.

The sometimes-X-Man Sunfire makes his first appearance, this time as an antagonist to the mutant team. Roy Thomas and Don Heck. X-Men, Marvel Comics, Vol 1, No 64, Sept 1963.

Since the Marvel Universe’s Big Bang in 1939, Marvel’s comics kept pace with science in vogue—or at least science that was familiar to its audience. Daredevil, a lawyer blinded by the same nuclear accident that gave him his radar sense, was introduced in 1964, the last major hero of the atomic era. By 1965 Marvel had largely begun to shift away from atomic rooted powers, incorporating more varied origin stories and backgrounds. The next wave of superhumans were largely alien: the largely-human-looking Inhumans, the Kree hero Captain Marvel and the cosmic wave riding Silver Surfer.

But the final end-point of the Atomic Era for Marvel was 1982’s The Death of Captain Marvel. The hero, a member of the Kree alien race, had faced down cosmic baddy after cosmic baddy. But what finally did him in was the unseen enemy: a cancerous growth owing to years of exposure to cosmic radiation. There for the Captain’s final moments were many of the same heroes who had benefitted from their own exposure to radiation. There, present at his bedside in his final moments, are The Incredible Hulk and The Amazing Spider-Man, two heroes whose lives were radically transformed by radiation. Both would later suffer the consequences of their mutation: the Hulk’s wife died after years of radioactive exposure from him and Spider-Man’s child was stillborn after a series of pregnancy abnormalities. Radiation was a destructive force, able to fell the mightiest of heroes.

The Atomic Era of Marvel Comic dies with the Captain. Much of the decade after the 1982 publication of the graphic novel was spent in fear of the final confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union.

The nuclear monsters of this era became smaller, the transformations more personal. When the company introduced superheroes again, they made the horror of metamorphosis more intimate.

New origins would arise in the times after that narrow window, going beyond the atomic era and into the space race and beyond. But the revived run of Marvel heroes solidified the concerns of the time, reflecting the power of the atom. And, in the way only comics can do, dramatized the need for survivors of the Atomic Age not only to survive, but to live on, more powerful than before.