Futures on Demand

In “Far Beyond the Stars,” an episode from the television series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (DS9), the commander of a futuristic space station hallucinates that he is a science fiction writer in 1950s New York. Far away from his twenty-fourth century life, Commander Benjamin Sisko (Avery Brooks) becomes Benny Russell, a black writer struggling against the prejudice of his managing editor, the condescension of friends, and the racism of local police.

The contrast between the twenty-fourth and the twentieth centuries is striking. While Sisko’s word is law on the DS9 bridge, Russell suffers petty humiliations in the magazine’s cramped offices. For instance, when fans request headshots of their favorite authors, editors plan a photo-shoot that excludes Russell and his colleague Kay Eaton, “played” in this hallucination by Kira Nerys (Nana Visitor) an extraterrestrial officer on DS9. Against Russell’s protest, editors argue that fans are not ready to know that women and black authors write their science fiction favorites: “As far as our readers are concerned, Benny Russell is as white as they are. Let’s just keep it that way.” This official lack of diversity on the magazine’s staff extends to the storyboard as well. When Russell proposes a piece featuring a black captain on a space station (that is, the premise of DS9) his editor retorts: “People won’t accept it. It’s not believable.” In the office and on the page, “Far Beyond the Stars” argues that the future remains constricted by the social exclusions of the present from which it springs.

Storylines like this ostensibly allow viewers to see how far they—and Star Trek—have come. Yet the franchise’s marketing and production histories complicate the inevitability of this storybook progress. Star Trek: The Original Series (TOS) famously gained prominence after its cancellation, and its reruns funded The Next Generation (TNG). Paramount Domestic Television only offered its syndicated cash cow TOS to stations that bought TNG—a financial strategy that collapsed the distance between an original and its next generation since both programs aired together. Therefore, while TNG and later Star Trek installments may present linear progress, this financial arrangement explodes any such timeline. Stations counted on viewers tuning in to TOS and hopefully staying on board for subsequent Star Trek voyages. While later series question the racial and gendered exclusions of TOS, this past continued to shape the franchise’s future possibility.

A financial engine powers Star Trek’s narrative of social progress. “Far Beyond the Stars” implies that social harmony comes to science fiction with social advance in the real world. However, while its historical vignette shows how financial strategy produced exclusions in the past, it implicitly tells viewers that inclusion follows a similar economic logic. Benny Russell’s unbelievable space station becomes DS9 reality once the fantasy becomes commercially viable. Though “Far Beyond the Stars” anchors future possibility to a multicultural present, social advance remains intertwined with marketing potential.

The juxtaposition of TOS and later Star Trek franchise installments both reveals progress internal to the franchise and continuities that refuse to leave the past behind. For instance, TOS opened each episode with Captain James T. Kirk’s (William Shatner) masculine mission: “to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and civilizations, to boldly go where no man has gone before.” While this statement promised that Star Trek would bring viewers to peoples and places hitherto unknown, its purportedly universal “man” evinced the gendered exclusions of a utopian journey. Fittingly, TNG revised TOS’s mission in the late 1980s by informing viewers that they would “boldly go where no one has gone before.” This shift to the gender neutral corrected past omissions to make Star Trek’s travels more inviting to female voyagers.

The revised opening monologue of Star Trek: the Next Generation.

This updated statement, however, does not include everyone. The persistent use of the phrase “new worlds” evokes a long history of inequality forged between “discoverers” and “discovered.” Though Kirk and Picard promise “to go where no man/one has gone before,” they expect to find “others” already there. Though Star Trek imagines social progress through the allegorical veil of extraterrestrial cooperation, its mission statement and naval metaphors reveal how the franchise maintains a Eurocentric vision of progress and discovery that excludes the rest from the West. By reconsidering Star Trek’s linear progress—a viewing practice facilitated by video on demand services such as Netflix, but prompted by the production history of Star Trek itself—we can see how Star Trek’s future remains mired in the past.

Imperialisms Past

Star Trek follows the intergalactic journeys of Starfleet, the scientific and military arm of the United Federation of Planets. At different points during the franchise, Starfleet confronts a rotating cast of alien antagonists including Klingons, Romulans, Cardassians, and the Borg. Scholars have read these various conflicts as permutations of the U.S.’s geopolitical conflicts gone interstellar. For example, Mark P. Lagon has suggested that TOS’s frequent interference with other civilizations reflected Cold War anxieties. DS9, in contrast, engaged pressing questions from the 1990s: the political futures of “liberated” peoples, new alliances with old enemies, the entrenched legacies of settler colonialism, and the economic challenges of collective markets.

However, to read Star Trek’s future as a simple reflection of the period in which each show was produced ignores how the franchise evokes longer histories of exploration and imperialism. The technological-organic Borg provide a case in point. By “assimilating” their opponents into their mechanical hive mind, the Borg eliminate their enemies’ individualism, liberty, and free will. Their violent practice of homogenization evokes a communist menace as imagined by the U.S. However, as technological hybrids, the Borg also evoke a dystopian future for Western capitalism wherein scientific advances bring dehumanization.

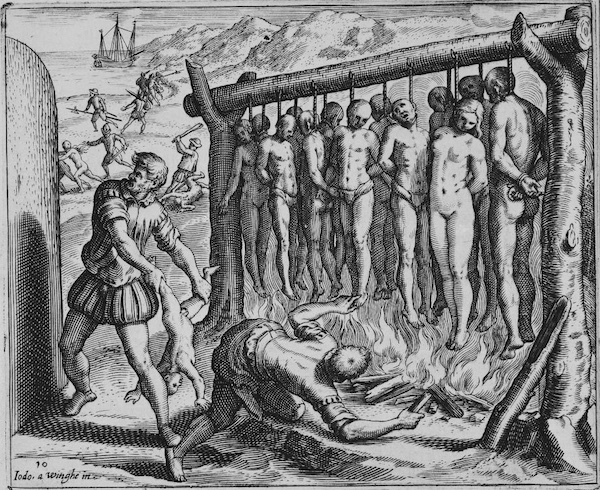

The Borg do not, however, only evoke the future. Scholars have linked the Borg’s famous hail, “resistance is futile,” to the Spanish requerimiento, a sixteenth-century text read to indigenous groups upon “first contact” with Spanish priests, soldiers, and explorers. Though this document ostensibly provided indigenous peoples with options—accept Catholicism or face the consequences—neither offered an alternative to Spanish dominance. Northern European powers encouraged this representation of a violent Spain—the so-called “Black Legend”—to place their own imperial projects in a better light. By reproducing this good cop/bad cop contrast in its speculative future, Star Trek takes a lesson from these historical antagonisms to idealize its own intergalactic police mission. For instance, while Starfleet purports to study other cultures and learn from them, the Borg “assimilate” groups that they deem worthy—those with biological advantages and relevant technology. Starfleet officially denies its militaristic might and cultural egocentrism through its comparison to the Borg, despite the fact that Starfleet employs violence and interferes with other groups throughout the franchise’s run.

Later installments from the Star Trek franchise question this official distance between Starfleet’s “pure” mission and the Borg’s indiscriminant aggression. In both TNG and Voyager, the Borg reflect Starfleet’s self-righteous party line back to its protagonists. For instance, when Voyager’s captain Katherine Janeway (Kathryn Mulgrew) endeavors to recover Seven of Nine (Jeri Ryan), a Borg of human origin, Seven of Nine retorts: “You have imprisoned us in the name of humanity yet you will not grant us your most cherished human right. To choose our own fate. You are hypocritical, manipulative … you are no different than the Borg.” Seven of Nine challenges Janeway’s (and Starfleet’s) attempts to separate their scientific studies from Borg domination. According to Seven of Nine, both groups impose their ideas of life on others. Such comments allow the franchise to critique its own future’s past. Against the self-righteous ideals of the franchise’s earlier installments, these later episodes challenge the purity of Starfleet’s mission. However, in so doing, these auto-critiques often undergird Starfleet’s power all the more. Rather than dismantling Janeway’s authority, Seven of Nine ultimately joins the crew while preserving minimal signs of difference. (The show never completely removes Seven of Nine’s mechanical Borg implants, though they selectively choose implants that don’t obstruct access to a form-fitting uniform). By incorporating alien cultures and listening to dissident voices, Star Trek suggests that it will always improve—progress—in linear fashion.

Captain’s Log

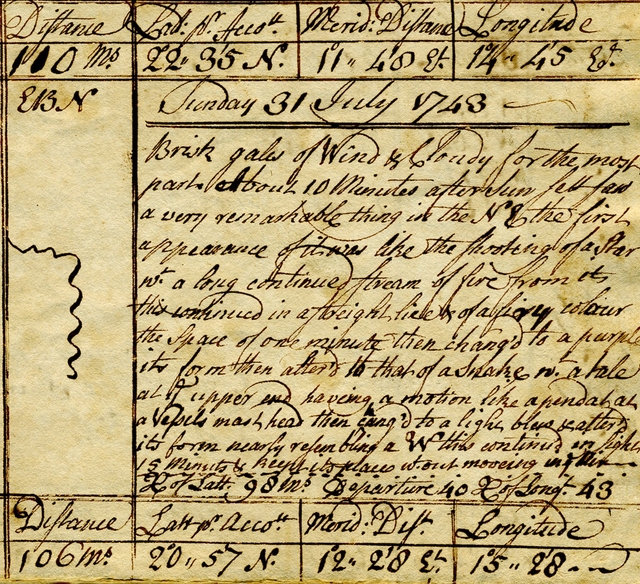

Star Trek’s official faith in the Starfleet mission is mirrored in the franchise’s opening narrative form, which borrows a convention from European “exploration”: the captain’s log. In the captain’s log, the show’s principal actor/highest-in-command introduces an episode’s primary theme or conflict through a voiceover. For instance, the first episode of TOS begins:

Captain’s log, stardate 1312.4. The impossible has happened. From directly ahead, we’re picking up a recorded distress signal, the call letters of a vessel which has been missing for over two centuries. Did another Earth ship once probe out of the galaxy as we intend to do? What happened to it out there? Is this some warning they’ve left behind?

While this first log entry explicitly deals with time (a vessel has been missing for two centuries) and the newness of the Enterprise’s mission (has another ship been here before?), it encapsulates these rhetorical questions of the future within a common naval form. The captain’s log makes the novelty of intergalactic exploration a future echo of past travel narratives.

As important, these captain’s logs align viewers with Starfleet, insinuating that what viewers “see” is not an impartial account. Instead, viewers voyage with Kirk, Picard, and Janeway, who set the stage for them. They are privy to official information recorded in captains’ logs, later destined for the Federation’s review. Though this narrative form provides a window into the workings of Starfleet and the minds of its captains, viewers are not asked to reconsider or disagree with these official interpretations. For instance, in preparation for an impending conflict with the Borg, Janeway reviews a series of captains’ logs in search of inspiration. Quoting Picard, she reads aloud: “The Borg are utterly without mercy; driven by one will alone: the will to conquer. They are beyond redemption, beyond reason.” Janeway’s citation does more than recite an official Starfleet position regarding the Borg. It provides a baseline assessment for viewers to “encounter” this alien antagonist. Though viewers’ opinion of the Borg may change, it will grow with that of Starfleet. Viewers are told to fear what Starfleet fears and to see from Starfleet’s vantage. The captain’s log demonstrates how Star Trek constructs its Other through Eurocentric channels—despite the intergalactic makeup of Star Trek crews.

A second technology shows how Star Trek inherits a Eurocentric history of discovery, order, and progress. The same episode discussed above opens with Janeway in the holodeck—a holographic playroom aboard Starfleet vessels that allows staff to recreate their home worlds (“Encounter at Farpoint,” TNG, season 1, episode 1), to unwind in imaginary jazz bars (“11001001,” TNG, season 1, episode 15), and to write their own 3-D novels (“Author, Author,” Voyager, season 7, episode 20). In this episode, however, viewers meet Janeway in a simulation of Leonardo Da Vinci’s workshop. Janeway negotiates with the inventor for corner space in his study since, as she argues, “just being here in your presence is inspiring to me.”

By turning to Da Vinci for inspiration, Voyager makes its intergalactic mission the progeny of European “innovation.” In such moments, rather than break with the past, Star Trek preserves a Eurocentric view of scientific advance that marginalizes its Others (even as it purports to “incorporate them” into its intergalactic crew).

However, to take the captain and his/her log as an all-powerful determinant of Star Trek’s content ignores the re-evaluations and revisions of authority that undercut this Eurocentric line. Throughout its multi-series run, Star Trek reconsiders its own representations of gender, race, and extraterrestrial otherness. In the DS9 episode “Trials and Tribble-ations,” Sisko and his crew travel back in time to TOS to prevent a bombing by the Klingons. To blend in, these travelers change their uniforms to match the color codes of TOS. Sisko glosses, “In the old days, operations officers wore red, command officers wore gold…” At this point, Lieutenant Commander Jadzia Dax (Terry Farrell) appears in a miniskirt, interrupting, “And women wore less.”

Dax smiles and twirls, presenting time travel as an amusing and exciting fan fiction. In fact, throughout the episode, Dax voices the fan’s desires: to meet Kirk, to go on the Bridge, and to run around this science fiction playground. However, Dax’s twirl and comment also present another possible interpretation of this Star Trek future past: a tongue-in-cheek reflection on its sexist uniforms and the diminished presence of women in roles of authority. Dax’s comment reveals the lack of progressive futures in Star Trek. By traveling backwards, the cast of DS9 inhabits a 1960s future that seems outdated by the 1990s.

Throughout this euphoric trip, characters repeatedly stumble over the inequalities of gender and race that marked Star Trek’s utopian future’s past. When one of his crew calls Sisko “Captain,” Sisko responds, “Lieutenant, actually. I didn’t want to push my luck.” Sisko provides no other explanation for this hierarchy change. Perhaps he strategically diminishes his own authority to prevent infelicitous questions or scrutiny by other Starfleet officers. However, on the heels of Dax’s remark, another possibility comes into view. As a black Starfleet captain—an impossibility in TOS’s “time”—Sisko would trouble the utopian terms of Star Trek’s future past.

Race appears most explicitly, however, in conflicts centering around Worf (Michael Dorn), a Klingon member of Starfleet. The Klingons famously changed appearance and personality over the course of Star Trek’s run. In TOS, they were presented as an alien stereotype of the Orientalized “Yellow Peril.” However, beginning with Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), the franchise reconceived the Klingons. In that film, Klingons appeared with an amalgamation of militaristic values, feudal habits, and “tribal” aesthetics. This difference is so striking that the DS9 crew cannot identify TOS Klingons and ask Worf incredulously: “Those are Klingons?” In showing how Klingons become unrecognizable in the course of Star Trek, DS9 remarks on the contingency of race as opposed to its transhistorical truth.

This does not mean that Star Trek eventually gets it right. To the contrary, it’s fairly simple to play the “who are they really supposed to be” game with Star Trek’s treatment of (intergalactic) race. While individual characters from non-terrestrial places may be fleshed out and given a range of emotional responses, the group as a whole is often restricted to a series of tropes. By making the Ferengis a race of intergalactic traders with oversized appendages and an addiction to “gold-plated latinum,” Star Trek merely updates Jewish stereotypes. Though Worf might complicate the general depiction of Klingons as “tribal” and bellicose by nature, his planetary brethren remain reduced to aggressive types.

An early episode of Voyager that focuses on B’Elanna Torres, a Human-Klingon “hybrid” (Star Trek’s official term for persons of interplanetary descent), shows how Klingon-as-racial-type remains subordinated to the more expansive possibilities of unmarked human. In Faces, an alien (Vidiian) splits Torres into two bodies, one Klingon and the other human, because her Klingon genome remains immune to a disease that is ravaging his people. In determining what traits belong to which body, it becomes painfully clear that the human B’Elanna is a fully fleshed-out character with whom the viewer is expected to align and sympathize. B’Elanna the human remains in an official Starfleet uniform while other aspects of her identity that would not seem biological become reified in the split. While the human B’Elanna continues to speak as the main character did, the Klingon B’Elanna speaks with a stereotypical Klingon accent. While the human experiences a range of emotion, the Klingon remains voraciously sexual, aggressive, and—like her genome—resistant. Rather than conceive of this “new” Klingon as an improvement on the racist imagination from the TOS past, Voyager shows how future changes reconfigure but do not ameliorate racist types.

“Time is Not Linear”

Star Trek does not leave the past behind, a point made in the very first episode of DS9. In its pilot, Sisko struggles with a disembodied alien population known as “The Prophets” that does not experience time in a linear fashion. Throughout the episode, these aliens return Sisko to a traumatic scene from his past: the death of his wife. After circling back to this moment, the alien consciousness asks Sisko why “you bring us here.” Sisko argues that he does not do the “bringing,” that the alien forces him to dwell in this particular moment. However, he finally acquiesces, “I never left this ship. I exist here. I don’t know if you can understand. I see her like this every time I close my eyes. In the darkness, in the blink of an eye, I see her like this.” As Sisko breaks down, he agrees with the alien consciousness, “No. [Time] is not linear.” Star Trek’s official narrative of progress that moves in linear fashion—expressed most clearly in the captain’s log—cannot address or repair the enduring experience of things like loss, discrimination, and suffering.

_Star Trek’_s future remains unfinished. With J.J. Abram’s two films, the franchise continues to look to its own past to rethink its future. But each new installment does not merely add more to the plot. Rather, it adds another set of hopes and failures to an already messy utopia.

With the rise of video on demand (VOD) services, viewers seem in control of their televisual destinies. They can abandon story arcs, travel back to greatest hits, and compare original versions to reboots. However, for a media franchise like Star Trek that spans over fifty years, VOD shows how fleeting our control may be. Star Trek illustrates not how far we’ve come, but rather how conflicts persist under allegorical veils and extraterrestrial makeup. While Star Trek smoothes over inequality with its intergalactic cast, the program routinely calls attention to the limits of future utopia. Thinking about the future always revises futures past, but that doesn’t mean that we leave them behind.