Dancers and Diplomats: New York City Ballet in Moscow, October 1962

I am indebted to the generosity of everyone who shared their experiences of the 1962 tour. My thanks to Jacques d’Amboise, Marlene Mesavage DeSavino, Paul DeSavino, Allegra Kent, Robert Maiorano, Teena McConnell, Arthur Mitchell, Nina Morozova, Frank Ohman, Suki Schorer, Bettijane Sills, Victoria Simon, Lyudmila Slutskaya, Carol Sumner, Violette Verdy, and Edward Villella. Unless otherwise marked, quotations in this piece are from my interviews with them. Thanks also to Erin Hestvik of the New York City Ballet Archives; to the Jerome Robbins Dance Division at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts; to Svetlana Khaitova and Slava Khaitov for their help with interpretation; and to John Marcy, Nathan Marcy and Eric Nichols for their notes and assistance with the historical photographs.

Robert Maiorano watched from the wings as dancers assembled onstage. On one side of the curtain were seventeen women. On the other side were 6,000 Muscovites filling the seats of the Palace of Congresses, the Kremlin’s new modern theatre. In between the dancers and the audience was the orchestra, which was playing the American and Soviet anthems in turn.

Weeks on tour had left the dancers exhausted. They had departed New York on August 29th—Maiorano remembered the date because it was his sixteenth birthday—and performed in several European cities before arriving in Moscow in early October, 1962.

This night felt particularly tense. “There were riots outside the theatre because the black market had sold extra tickets,” Maiorano remembered. “Plus the fact, of course, that this is the day that Kennedy told Khrushchev to get out of Cuba or else.”

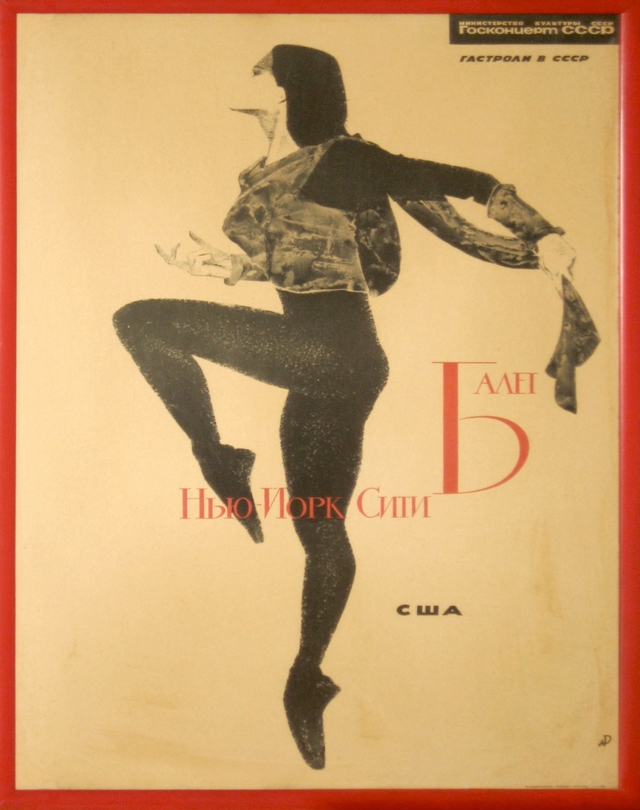

Throughout the 1950s, the United States and the Soviet Union dispatched dancers and musicians across the globe in a kind of cultural proxy war designed to affirm the virtues of liberal democracy and communism. As art forms that don’t rely on shared language to convey meaning, music and dance were particularly suited to cultural exchange. Modern dance companies led by the choreographers Alvin Ailey, Martha Graham, and José Limón conducted successful tours of Asia and South America; New York City Ballet (NYCB), San Francisco Ballet, and other ballet companies followed.

Soviet officials considered Russian achievements in ballet to be unsurpassable. In a widely published 1955 editorial, journalist George Sokolsky disagreed. “The United States need not hang its head in shame in this field,” he wrote. “This is sound propaganda and ought to be encouraged.” Someone at NYCB apparently concurred, because several copies of the editorial were carefully cut and pasted into the company’s scrapbook.

In 1959, the Soviet Union sent the famed Bolshoi Ballet on a tour of the United States. A total of 900,000 requests poured in for 165,000 tickets, and they were reportedly traded for up to $150 ($1200 in today’s currency). The Bolshoi’s reviews in American papers verged on the ecstatic, but the observation that some of their choreography was old-fashioned—for Western tastes—resulted in accusations in the Soviet press that the U.S. government wasn’t fully committed to cultural exchange. Someone, they argued, was trying to undermine the Bolshoi’s successful presentation of Soviet culture.

In response to the Bolshoi’s tour, the State Department sent American Ballet Theatre to the Soviet Union in 1960. It was a decision that dance critic John Martin predicted would result in “profound national humiliation” for the United States. He derisively called American Ballet Theatre the “Gopher Prairie Civic Ballet” and concluded that the panel giving advice to the State Department should do its patriotic duty and rescind their recommendation. Contrary to Martin’s dire predictions, American Ballet Theatre was well-received. Premier Nikita Khrushchev made a surprise appearance at their closing night in Moscow, after which he hosted an impromptu cast party.

Members of the American Ballet Theatre take a curtain call after a performance in Moscow, 1960. Library of Congress

The State Department wanted another ballet company to tour the Soviet Union, and New York City Ballet was ready to go. The company was co-founded by arts patron Lincoln Kirstein and choreographer George Balanchine, who was born Georgi Balanchivadze to a Russian mother and Georgian father living in St. Petersburg. Balanchine hadn’t always been keen to bring the company to the Soviet Union, and had previously flatly declined. Returning to his drastically altered home country was a difficult prospect, but he was eventually persuaded that taking his company to the U.S.S.R. was virtually a patriotic responsibility.

Company manager Betty Cage announced NYCB’s willingness to travel to any Iron Curtain countries of interest to the State Department, as long as they could also incorporate stops in Western Europe. The State Department wanted the company to spend more time in the Eastern bloc, and Cage replied that an extended tour of “hardship posts” would be too tiring for the dancers. NYCB was also concerned that the Soviets might detain Balanchine, and Cage asked that he be provided with diplomatic immunity. Company administration grew increasingly frustrated as the State Department’s negotiations with their Soviet counterparts dragged on, and in April 1962 Lincoln Kirstein sent a terse telegram to the Department’s Cultural Affairs Office: “Due to pressure of practical existence, we must now schedule fall and winter season in the U.S.” The hard bargaining evidently worked, because three weeks later the company and State Department were debating travel details.

The company would begin its travels in Western Europe, then continue on to Moscow, Leningrad, Kiev, Tbilisi, and Baku, Azerbaijan. All personnel were subject to final approval by the State Department, and “improper conduct” would result in dismissal from the tour. Per the carefully calibrated principles of Cold War reciprocity, NYCB would trade places with the Bolshoi, which would embark on a tour of the U.S. and Canada. “All disputes arising from the present contract,” the agreement noted, “shall be resolved by means of friendly negotiations.”

Betty Cage initiated a flurry of communications with Goskontsert, the Soviet cultural exchange agency. When American Ballet Theatre toured the U.S.S.R. in 1960, they were denied access to Russia’s two greatest theatres, the Bolshoi in Moscow and the Mariinsky in Leningrad, which had been renamed “Kirov” in honor of an assassinated Party official. Goskontsert tried to schedule a lesser venue for the Leningrad opening; Cage made it perfectly clear to Goskontsert that anything other than the Mariinsky/Kirov was unacceptable. Cage requested the technical specifications of the theatres in each city so they could plan their repertoire; the Goskontsert official, apparently affronted by this request, told her she didn’t need them because all their stages were suitable for ballet. “We have also taken counsel with our specialists who are well acquainted with your ballets and they completely share this point of view,” he wrote.

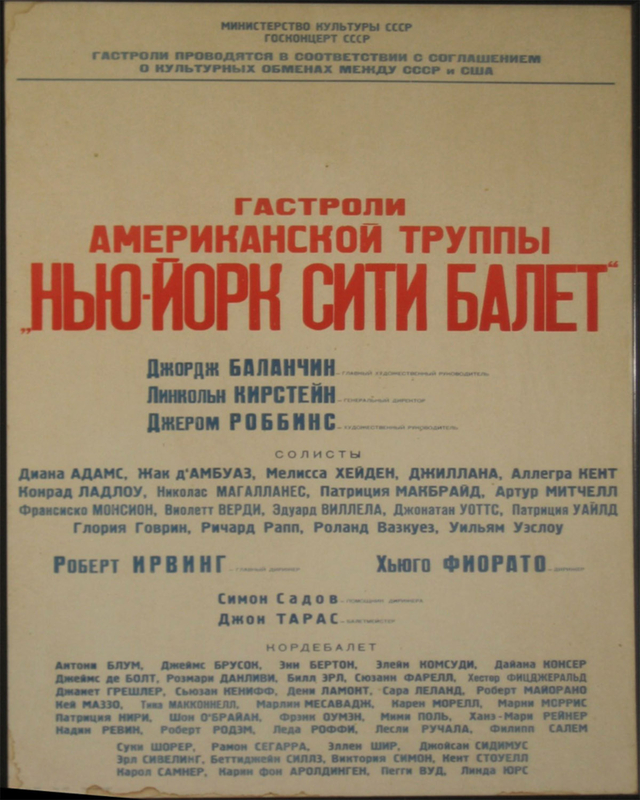

New York City Ballet brought 61 dancers, ranging from 16-year-olds fresh out of the School of American Ballet, to established principal dancers in their late 20s and 30s. They were accompanied by Balanchine, Kirstein, Betty Cage, and a company doctor; four conductors and pianists, who had the task of rehearsing the Soviet orchestra that would travel with them on tour; their stage manager and a small crew; four wardrobe personnel; and chaperones for the dancers under age 18. They would be met by interpreters provided by Goskontsert and attachés from the U.S. Embassy.

After five weeks in Europe, the company’s plane touched down in Moscow on October 6th. “The runway was flooded with lights, and there were photographers and flowers, and it was just an amazing scene,” remembered dancer Marlene Mesavage. Balanchine descended the airplane’s stairs with ballerina Diana Adams, and they were ushered into the airport lobby to meet the press. A contingent of Bolshoi dancers who’d been left out of their company’s tour met their American counterparts with bouquets in hand. Waiting with them was Balanchine’s brother, Andrei Balanchivadze, who was a successful composer in Georgia. The brothers hadn’t seen each other since they were children in St. Petersburg, over 40 years before. They were the last living members of their immediate family; their parents were dead, their sister killed in a German air raid on Leningrad.

Meanwhile, a quieter reunion was taking place on the tarmac. Wardrobe mistress Sophie Pourmel hadn’t returned to her home country in seventeen years. She wrote to her siblings, unsure if she even had the correct address, and was overjoyed to receive a reply from her brother: “My heart is bursting. Come, come.” Now in Moscow, walking down the airplane stairs, she heard people calling her nickname, Sonja. Her siblings had somehow hitched a ride with the press corps. She was so overwhelmed she froze on the steps, and her brother walked up to help her down. They stayed together in the hotel lobby until two o’clock in the morning, talking about their parents’ lives during the war.

The company was accommodated in the Hotel Ukraine. Dancer Bettijane Sills remembered a lobby the size of Grand Central Station, with elevators that could move cattle. One of the middle floors was inaccessible from the elevator, and the dancers surmised it to be the location of the hotel’s listening equipment. They’d been warned by the State Department that their rooms would be bugged, and that they should be constantly careful with their words; the waiters at the breakfast table could be reporting back to the KGB. They were told that if they absolutely had to say something of a political nature, they should write it out and flush it down the toilet.

Their first impressions of Moscow were unflattering: imposing and claustrophobic, spooky, dour, and unrelentingly gray. However, they still felt warmly welcomed. “Wherever we went we had kindnesses from the people,” remembered dancer Teena McConnell. Most of the people on the tour had never encountered conditions like those in the Soviet Union, and previous experience colored their interpretation of what they were seeing. Dancers remembered empty shelves in the stores; Sophie Pourmel was relieved the stores were open, because that meant there was food available. Conditions in the Soviet Union were better than when she had left. The dancers struggled with the food, which featured an abundance of bread and potatoes, and rather few vegetables. They were each allowed to bring a foot locker, which they could stuff to 106 pounds with non-perishables, toilet paper, and cleaning supplies. They brought Sternos and pooled together Spam and tuna to bolster their diet.

Principal dancer Violette Verdy felt that her life during the Nazi occupation of France prepared her for conditions in the Soviet Union. She observed the acute culture shock experienced by many of her colleagues. “Americans had no idea how awful countries are after wars and after repression, and with certain types of regimes,” she said. “They had never seen it firsthand.”

Robert Maiorano also took the demands of touring in stride. “I grew up in a cold-water flat in Brooklyn, my mother wasn’t a great cook, and we had bedbugs in Brooklyn, you know? So this wasn’t shocking to me, this wasn’t appalling to me, this was still relatively first-class.”

But the most difficult part of the tour, it seems, was the unshakeable feeling of constantly being watched. Teena McConnell, who as a minor was accompanied by her mother, felt that the dancers were under silent observation. She believed it was mostly curiosity, but it could certainly appear suspicious. Hotel guests had to leave their room keys with a matron on each floor whenever they left their rooms, and one day McConnell turned in her key and went down to the lobby to be bused to the theatre. She realized she’d forgotten something and dashed back upstairs, bypassing the matron’s desk. She soon discovered she didn’t need her key, because hotel staff were in her room, rifling through her suitcases. She asked them what they were doing, and they immediately exited without explanation. The matrons knew everyone’s whereabouts; when company members congregated in one room, the room’s phone would ring, and they were told to pick up their keys and go to their own rooms. Company electrician Paul DeSavino said it was like being in kindergarten.

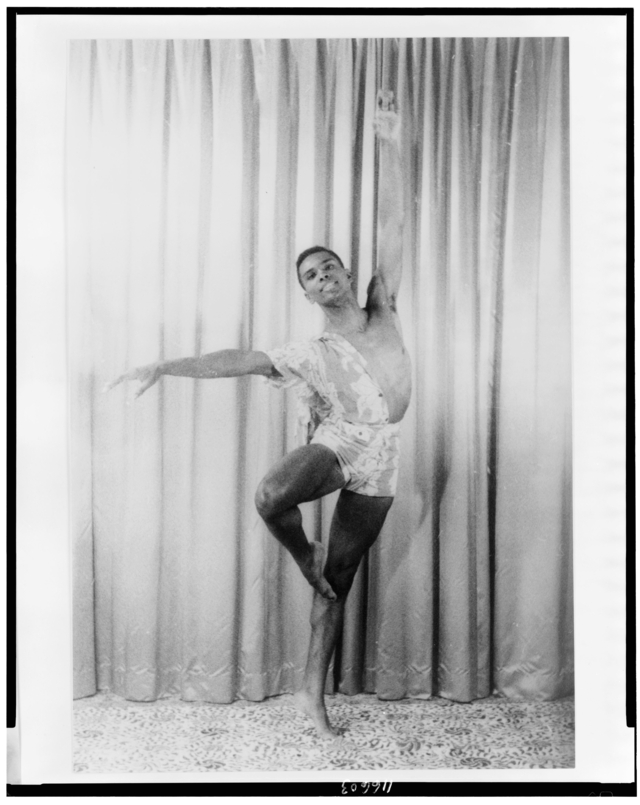

Arthur Mitchell recalled the strain and uncertainty of traveling in the Soviet Union. “We all had to be on our guard all of the time, because you didn’t know who was who, you didn’t know who was KGB. We didn’t know who was there as a spy.” As an African-American principal dancer, Mitchell had no chance of anonymity, and constant observation was exhausting, even if it was in admiration. He felt that the dancers were always on display.

Interactions with local people were closely proscribed, and it could be dangerous for Soviet citizens to approach foreigners. Marlene Mesavage remembered that people on the street in Moscow were often unwilling to make eye contact with the Americans, which they found disconcerting. The penalty for arousing the suspicion of the police was demonstrated when a Russian man struck up a conversation with a group of dancers on the train. “As soon as we got to the next stop,” said principal dancer Edward Villella, “two burly guys just grabbed him, took him off the train, and we watched him get beaten.”

It was easy for the American visitors to be isolated, as very few spoke Russian and they had a rigorous schedule with regimented mealtimes. Their interpreters were always on hand, and functioned as both intermediaries and buffers between the dancers and the public. Some of the dancers did become friends with the Russian staff, and they were able to visit tourist sites. Still, they felt very constrained. Principal dancer Jacques d’Amboise remembered the attachés from the State Department reading the company’s mail. The dancers felt they were being scrutinized onstage and off.

Despite the enforced divide between performers and audience, the dancers were encouraged by the State Department and company administration to give small gifts to locals, although they had to be very discreet in doing so. Teena McConnell offered a piece of chewing gum to the hotel’s elderly elevator operator, and was flummoxed when the woman waved it away, shushing her with a finger to her lips. The next time she went in the elevator, the woman signaled that she could take the gum, which she slipped into her pocket with a conspiratorial “shh.” Despite the danger, people sometimes approached the company and asked for goods; dancer Frank Ohman said one man offered to buy the shoes off his feet. Jeans were particularly coveted items, as electrician Paul DeSavino discovered when he gave a pair of jeans to a young man, a student who followed the company around Moscow.

It was a small thing for him to give away a pair of thoroughly used, unwashed work jeans, but the student was overjoyed. In turn, Soviet ballet fans gave the dancers flowers.

The dancers were coming off five weeks in Western Europe, but they barely had time to catch their collective breath before they launched into stage rehearsals for their run in Moscow. The costumes, sets, and lights had been shipped ahead and delivered to the Bolshoi Theatre via horse-drawn wagons. DeSavino recalled the hard-working stagehands of the Bolshoi, “sensational” middle-aged women who kept everything running smoothly despite the language barrier. The American stage crew came equipped with an English-Russian glossary of theatre terms, but communicated mainly through pointing. During the Moscow run, the company alternated between the historic Bolshoi and the massive Palace of Congresses in the Kremlin. The dancers were sharing space with the Bolshoi Opera—where the American singer Jerome Hines was guest starring in Boris Godunov—and were displaced from the Kremlin for the 150th anniversary celebrations of Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia. This was particularly stressful for the stage crew, who had to shuttle the sets and lighting equipment between the two theatres.

Young corps member Teena McConnell and principal dancer Allegra Kent used the same phrase to describe their experience of performing on the tour: tremendous pressure. “We were determined to be the best we possibly could be, because we were representing America, but also Mr. Balanchine and New York City Ballet,” explained Arthur Mitchell. Given ballet’s long history in Russia, the dancers were excited and anxious about performing before such knowledgeable audiences.

Marlene Mesavage vividly remembered opening night. “The entire company was gathered onstage, and the curtain rose, and they played the Soviet anthem followed by the American. I have to say that I really felt the significance of the occasion. Tears welled in my eyes when I heard ours, and I just felt such tremendous pride and attachment to my country. I felt that art was transcending our political differences. It was extraordinary.”

Opening night in every city on the tour was attended by Party officials, and the response was generally tepid. Even if those in attendance genuinely appreciated the company’s work, they were reluctant to demonstrate overt enthusiasm for anything American. “I remember finishing my variation in Agon to thundering silence,” Edward Villella wryly commented.

The dancers were unsure what the audience would like, as Balanchine’s choreography was very different from the 19th century classics and the 20th century staples of Soviet ballet repertoire. Soviet choreography was story-driven and incorporated mime; New York City Ballet brought abstract, pure-dance pieces or works with minimally sketched plots. Lyudmila Slutskaya saw the company perform at the Kremlin. She was twenty-two, around the same age as many of the dancers. It was a one in millions chance that she got a ticket; she was dating a young man whose mother worked in the government, and who had procured two tickets for the ballet. She had participated in children’s dance classes and seen children’s theatre shows, but she’d never seen the Bolshoi. What Slutskaya saw astounded her. New York City Ballet felt like the rock and roll music being smuggled into the U.S.S.R., and to see it performed onstage, with official sanction from the government, was startling. She wasn’t able to discuss it with anyone, because her family and friends weren’t able to attend—and because people were scared to talk about anything Western.

One of the most avant-garde pieces performed was Agon (“contest” in Greek), the product of the close collaboration between Balanchine and Igor Stravinsky, who composed a work based on 17th-century French court dances. The ballet is performed by twelve dancers wearing plain black and white costumes, in a minimalist setting. It is both courtly and nervy, employing traditional forms to create a disquieting atmosphere evocative of modernism and the Cold War. The dancers intertwine their bodies in otherwordly yet frankly sensual positions not found in the academic ballet vocabulary.

Balanchine also took the bold step of casting a black man and a white woman—Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams—in the central pas de deux of the ballet. Mitchell was emphatic about the social significance of the casting of the ballet, which was choreographed in 1957. “That was an amazing, amazing thing for him to do. That was defying what society was all against,” he said.

Audiences loved Agon. “Every second night from that time on, the audiences were just unbelievable,” said Edward Villella. “We got the politics on the first night, and we got humanity from the second night on.”

Soviet critics were less impressed with Agon, and complained that Balanchine’s work was cold and somewhat inhuman. One wrote that the ballet “is nearer to mathematics than to art… this work is being addressed to our brain, says nothing to our heart.” Another charitably wrote that Stravinsky was an outstanding composer, but Agon “could hardly be one of his best works.” Anna Ilupina of The Moscow News flatly called the ballet a “morbid tragedy.”

Critics were initially hesitant to praise the company, partly due to the dangers of showing real enthusiasm, and partly due to artistic differences. Anna Ilupina acknowledged the company’s success with the audience while denying that anything they offered was truly intriguing. “The troupe led by Balanchine has apparently awaked a great deal of interest, despite their having brought nothing that could be termed basically new,” she wrote. She even employed the unusual tactic of praising the audience for their “customary hospitality,” interpreting the applause as praise for the dancers “who displayed real heroism in overcoming the intricate steps, and who obviously defied the cold abstract quality” of the work. In other words, the dancers succeeded in spite of the music and choreography, not because of it, and the audience was applauding out of sympathy. Balanchine, Ilupina believed, was at his best when he hewed closest to the traditions of his Russian predecessors. She praised dancer Suki Schorer by comparing her to “our Katya Maksimova who is being so greatly admired now by the Americans.” A favorable comparison to a Russian dancer was a safe way to issue compliments, while reminding readers that the Bolshoi was equally formidable.

After observing the NYCB dancers in their daily ballet class, Natalia Roslavleva praised the visitors’ musicality and work ethic. “Their discipline, resilience, readiness for hard work and stamina are really astounding,” she wrote. Audiences were particularly enraptured with the Americans’ speedy footwork. Carol Sumner was stunned to get three bows for her solo in Raymonda Variations. “I don’t think they ever saw anybody move that fast,” she remembered. Roslavleva interpreted the American style of dance as reflective of national traits: “athleticism, endurance, a sense of humor and the rationalism of the American nation.”

“Rocky Staples, cultural attaché, informed us that the embassy takes no responsibility for dancers,” Lincoln Kirstein recalled of the onset of the Cuban Missile Crisis during the tour:

In case of our internment, he has no authority to intervene. In the Kremlin at the Palace of Soviets, brilliant performance of Agon, with the crowd cheering Arthur Mitchell (“Meech-elle, Meech-elle”). On the way to the hotel, rumbling tanks in back streets. The kitchen made a special effort to prepare a feast; the maids frighteningly sympathetic. Betty Cage and I in cold sweats. Balanchine cheerful: I’ve never been to Siberia.

In Washington, revelations of missiles in Cuba sent the Kennedy administration into a diplomatic and military scramble. In Moscow, Edward Villella finished his solo in Donizetti Variations to prolonged rhythmic applause. When the audience refused to stop clapping after 20 curtain calls, he walked to the front of the stage, nodded to the conductor, and did the whole thing over again. “The interpreters were telling me that you could count the number of encores in the history of the Bolshoi on one hand,” he remembered.

Both the State Department and the dancers were determined to carry on with the performances, even if they were nervous about the crisis. The rigorous performing schedule and the unfamiliar food were taking their toll, and presented more immediate concerns than the Soviet vessels moving toward Cuba. Dancers were suffering stress injuries and a condition they named “Moscow tummy,” causing the healthier among them to take on extra parts. “I was dancing four ballets a night, hard ones,” said Carol Sumner. “Everything else to me was all irrelevant.” Victoria Simon remembered being thrown on for Scotch Symphony, a ballet she’d never even understudied. She was taught the ballet’s first movement in the half-hour before curtain, and then was taught the third movement in the wings during the second movement. “I kept saying, ‘Just pull me and push me in the right direction!’”

Allegra Kent was also taking on extra roles, while coping with anxiety over being separated from her young daughter. “I thought, Oh my God, my daughter is in New York City and I’m in Moscow,” she recalled. “It’s just horrible.” Kent danced multiple leading roles in almost every performance, including the pas de deux in Agon opposite Arthur Mitchell. “My routine was to have breakfast, go to the theatre, rehearsals, get ready, performance, dinner after the performance, come home, go to sleep,” she remembered.

Most of the dancers remembered receiving bulletins from the U.S. Embassy about developing events. Some dancers thought they were given incomplete information because the State Department didn’t want them to panic. Others thought they were given accurate information for the same reason: the Embassy didn’t want speculation to take the place of facts. Some of the dancers even remembered reading a transcript of Adlai Stevenson’s speech at the UN, and Kennedy’s address. Others felt adrift, only learning the extent of the crisis when they returned home. Many of the dancers assumed that if the situation became truly dire, they would be sent back to the United States, and the Bolshoi would be returned to Moscow. There was a precedent for this expectation, as previous state-sponsored tours had been cut short due to political tensions. If they weren’t being shipped back, war probably wasn’t imminent.

Some dancers recalled being told to leave the Embassy—where they went to get hamburgers to supplement their hotel food—because there was going to be a planned demonstration. Young people tumbled out of buses, lobbing rocks and ink bottles at the Embassy’s honey-colored stone walls.

Dancer Teena McConnell and her mother probably had the most frightening experience of the crisis: they were walking near their hotel when they encountered a mass of chanting people. Men in the crowd threw lit cigarettes and tried to burn her mother’s coat, and they beat a hasty retreat to the hotel. In a report for the CIA, an attaché for the U.S. Air Force wrote that the Soviet government planned a large demonstration for October 27th, when they had troops installed on side streets around the Embassy to maintain control of the crowd of around 5,000 recruited youths. This was likely the demonstration Teena McConnell and her mother encountered, and although most of the demonstrators were minimally enthusiastic, some clearly took it as an opportunity for common malice.

At other points, the reaction to the crisis seemed surreally mundane. The Australian ambassador in Moscow extended invitations to company members, and Marlene Mesavage and Paul DeSavino went to dinner at his residence. As they were eating, people in the street started overturning cars and setting them on fire. The ambassador calmly explained that it wasn’t anything to worry about—just something to make a headline. They finished their dinner and walked back past smoldering cars.

The State Department staff could perhaps have done a better job communicating to the dancers that life in the Soviet Union was proceeding fairly normally, as the visitors had no barometer for interpreting displays of military power. “One morning we got up and we saw all these tanks and airplanes and soldiers, and we said, Oh my God, we’re at war!” remembered Arthur Mitchell. The company gathered in the dining room and anxiously discussed their options for getting out of the U.S.S.R., until someone finally told them it was a rehearsal for a parade celebrating the October Revolution.

In truth, the Kennedy Administration did not inform Ambassador Foy Kohler of the crisis, and the Embassy remained in the dark for the first six days, until they received a copy of Kennedy’s address to the nation. In his memoir, NYCB’s attaché, Hans Tuch, wrote that he wasn’t aware of the crisis until it was almost over, and wasn’t aware of the extent of the situation until a letter arrived from his wife, advising him to move further east to escape the range of American missiles. The Embassy had been charged with shaping public perceptions of the United States, and NYCB’s performances proved a fortuitous tool. In his report, the Air Force attaché wrote that “the most talked-about event in Moscow during the week of the crisis was the opening of the New York City Ballet.”

In a 1976 interview, Betty Cage reflected that “perhaps we over-reacted, but we had visions of ourselves being impounded and put in concentration camps being kept for the duration, because it looked as though war was possible, so it was a real panic.” The company was also worried that the Soviet government would attempt to detain Balanchine, as they’d originally feared. In the moment, the possibility of war and detention seemed very, very real. Years later, Lincoln Kirstein wrote of the strain of the crisis: “The tension, indeed the terror, of those few days and nights, without a blow ever being struck in anger, were more demoralizing than anything I had ever encountered.”

It was at this point that Robert Maiorano was in the wings of the Kremlin’s theatre, listening to the national anthems. “They’re all on stage, vulnerable, 17 girls standing,” he recounted. “And then when the curtain went up on Serenade…the whole audience, 6,000 people, rose up at the same time. And then they cheered.”

To be received with such generosity at a time of great political tension made a deep and lasting impression on the dancers. They felt that they were cultural ambassadors, with a mission to connect on a human level. On October 28th, when Radio Moscow announced that the Soviet Union had accepted the U.S. proposal to end the standoff, the company closed its run in Moscow at the Bolshoi Theatre. The applause was so vociferous that Balanchine came on stage to ask the audience to let them leave. Fans were still clamoring for an encore even as the company’s bus pulled away from the theatre.

The Bolshoi Ballet’s tour began auspiciously. Advance ticket sales had run up to $600,000 ($4.7 million today). Adlai Stevenson attended the New York premiere as the special guest of Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. UN Secretary General U Thant, who would mediate between the two powers to resolve the crisis, was also in attendance. Sol Hurok, the Ukrainian-American impresario who helped fund both the Bolshoi and NYCB tours, commented: “As long as they keep dancing and the diplomats keep talking, we’ll have no war.”

But the crisis—and the press coverage—only intensified in the days to come. Bill Lockwood, who was presenting the Bolshoi’s run in San Francisco, found his plans for a sell-out week derailed by the announcement of the blockade on Cuba. The potential audience stayed home. Lockwood didn’t believe that San Franciscans were trying to send a message to the Soviet Union; they were simply too preoccupied to think of going to the ballet (Throughout the Cold War, protests were frequently staged outside theatres when Soviet groups toured the United States).

By the time the Bolshoi circled back to the East Coast, the crisis had abated. The Kennedys took great pains to make the company feel welcome. President Kennedy’s first social outing after the crisis was to the ballet; he reportedly clapped louder and longer than anyone in his section, and went backstage with Ambassador Dobrynin to greet the dancers. Jackie Kennedy hosted the dancers at the White House, with Mrs. Dobrynin on hand as interpreter, and took young Caroline to watch the Bolshoi’s leading ballerina, Maya Plisetskaya, in rehearsal. The President’s mother and his brother Ted hosted the company on Cape Cod, throwing a Thanksgiving-style dinner party for Plisetskaya’s birthday.

New York City Ballet continued its tour, through Leningrad, Kiev, Tbilisi, and Baku. Everywhere, they were enthusiastically received. The dancers appreciated the opportunity to perform in the historic Mariinsky Theatre in Leningrad, and their run in Balanchine’s ancestral hometown of Tbilisi was a smashing success. At the end of thirteen weeks on tour, they returned to Moscow to fly back to New York via Copenhagen. A small crowd gathered on the tarmac, despite a developing snowstorm. Paul DeSavino looked out the window and was surprised to see the student to whom he’d given his jeans amongst the crowd of well-wishers. He was running alongside the plane, showing off the jeans, which he’d had washed and pressed. “It was the start of a blizzard, so it was really coming down, and there was this kid out there with a big smile on his face, pointing down to his jeans,” he marvelled. The student had waited weeks for the chance to see them off.

Betty Cage had orchestrated publicity from afar, and reporters mobbed the company when they landed in New York. “A blonde mother with a ponytail hairdo rushed through Customs at Idlewild Airport yesterday evening, wanting more to see her 2-year-old daughter than to reflect on the eight-week tour of the Soviet Union,” wrote the New York Times. The “blonde mother” was Allegra Kent, and photographers made sure to get a shot of her reunion with her daughter.

In his report for the State Department, Hans Tuch wrote of the success of the tour: “I believe that the New York City Ballet made a deep and lasting impression on Soviet artists and intelligentsia who saw their performances and with whom they came into contact…New York City Ballet deserves official recognition for its contribution to the U.S. objectives of the exchange program.”

But the dancers were most impressed by the connection they forged with the audience. “You know, art does bring people together, because nobody cared at the theatre,” Carol Sumner remarked.

“I’m so glad I had that experience, because I look at the world in a totally different way,” Teena McConnell recalled. The 1962 tour gave her the drive to see as much of the world as she could, and marked the beginning of her extensive travels. The dancers were deeply affected by what they saw in the Soviet Union. “It changed us… We grew up fast,” Sumner said. “Never complained about much after that.”

For Violette Verdy, the tour was an epochal event in the history of the art form. “It was the meeting of all those conceptions of ballet,” she remembered decades later.

And the meeting of national identities recognizing each other, and the blending of all those schoolings, and all those teachers and their legacies coming to life together, and it was incredible. I mean, a fantastic cocktail, you know. Just an incredible richness, a huge patrimony, huge.

Like a bouquet. A great big bouquet.