The Invention of Wireless Cryptography

Wireless technology has always involved a delicate negotiation between state security, secrecy, and citizen oversight.

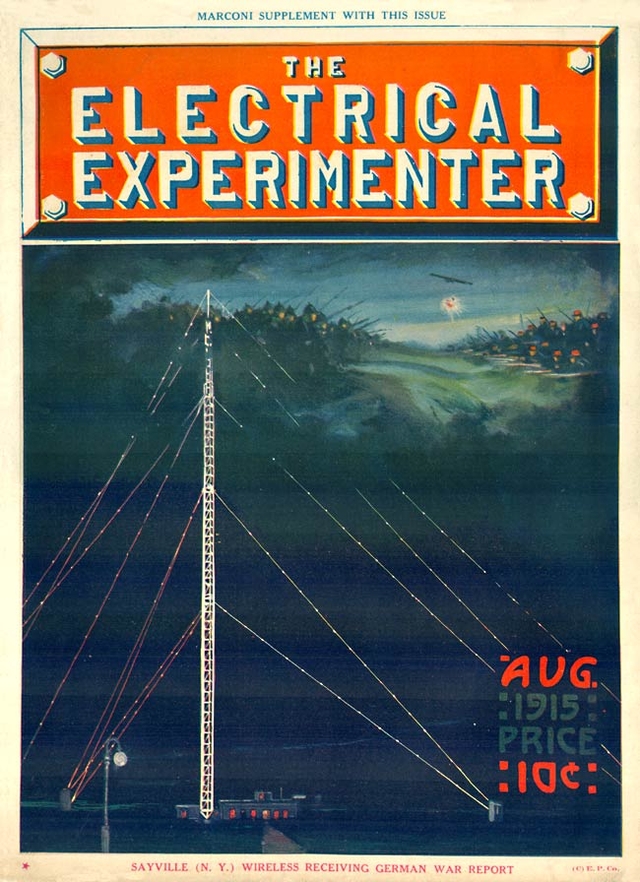

The wireless telegraph station in Sayville, New York was one of the most powerful in the world. Constructed by the German company Telefunken in 1912, it served as a transatlantic relay point for diplomatic messages and business communications. It was a beacon among amateur wireless enthusiasts around the United States who could tune their home-made sets to the station’s nightly press dispatches. All of this changed when one of those amateurs uncovered the station’s true purpose. The Navy seized the station in 1915 on suspicion of relaying covert commands from the German Empire to U-Boats in the Atlantic, and a congressional bill was introduced to ban all civilian wireless activities from the airwaves. The interruptions to the story that follows consist of excerpts from Hugo Gernsback’s serial novel The Scientific Adventures of Baron Münchausen, which ran in Electrical Experimenter magazine right as news of the wireless cryptography scandal unfolded.

Static was always a problem as the summer heat rolled in.

Situated on a hundred-acre plot along the Long Island coastline and “dropped in a mosquito-infested field,” the Sayville wireless plant began experiencing the seasonal interference that comes with longer days and warmer weather in May 1915. At that point little older than the twentieth century itself, wireless telegraphy (a precursor to radio) was not an entirely reliable medium. Debates over the precise cause of this seasonal static soon broke out among the tinkerers and oddballs of the early wireless community. Some said that radio waves experience more interference as they propagate through denser, more humid air. (There was still talk at this time of the existence of a luminiferous aether.) Others speculated that because messages came in clearer at night, the heat of the summer sun on the station’s aerials was affecting their transmitting capabilities.

By late summer, Sayville operators announced that interference from so-called equinoctial storms was forcing them to restrict messages to official government communications. Some commenters quipped that wireless buffs were getting cause and effect mixed up: “they said the electrical effects [of the station] absorbed all the moisture and made Sayville dry as a Saratoga chip,” referring to the potato chip first invented in Saratoga Springs, NY in the 1850s. Perhaps the station itself was altering its surrounding atmospheric conditions.

When one contemplates the marvel of sculptured sound on a graphophonic record, and realizes that from the cold vorticity of line there may magically spring the golden lilt of the greatest song voice that the world has ever heard, then comes the conviction that we are living in the days of white magic.

At the rate of a dollar per word, civilians and government officials alike could relay messages from Sayville to its sister station at Nauen, Germany. In addition to commercial and diplomatic communications, Sayville sent out press dispatches every night at 9:00 that amateurs around the country tuned in to using their hand-built crystal detector sets. Receiving transmissions from the Sayville station was the gold standard for both wireless sets and their owners (who referred to themselves as ‘muckers’), and electronics manufacturers regularly promised easy reception of Sayville transmissions in advertisements for their products. The static that came with summer weather was nothing new for these wireless professionals and amateurs. Seasonal disturbances were simply a part of the natural rhythms of a new medium.

A 1907 crystal radio receiver housed in mahogany, designed by Harry Shoemaker in 1907. History San José, Perham Collection

But this summer, Telefunken, the German company that owned the station, seemed absolutely determined not to let any atmospheric or climatic disturbances interfere with the transmission of messages between Sayville and Nauen. By June, to the surprise of the wireless community, the Sayville station could be heard clearly at much greater distances. Local observers reported that three 500-foot towers had been added to the system of aerials atop the plant. These new aerials were coupled with an increase in transmitting power from 35 to 100 kilowatts, effectively tripling the plant’s abilities “in order to insure absolute communication, under all conditions and particularly through the heavy static obtaining during the summer weather.” The Electrical Experimenter reported that Telefunken had imported the new equipment from Rotterdam, a Dutch port city clinging to its neutrality between Germany to the east and occupied Belgium to the west.

The outbreak of the great war of 1914 found me in the midst of the study of several new inventions which I was trying to perfect. But I welcomed the war, nevertheless, with a glad heart. Here at last was my long hoped for chance to get even with Prussia against whom I had nursed a growing hate during the past few years. My ‘révanche’ was at hand.

‘Yes, Monsieur le Président,’ I replied fervently, ‘it was my misfortune to be born in Prussia, but I assure you that there is to-day no more ardent, patriotic Frenchman in France than myself. Down with the tyrant Prussia!’

The newly expanded station introduced a number of groundbreaking innovations designed by Telefunken, including a new lettered keyboard that produced a perforated paper tape of transliterated Morse code messages ready to be fed into an automatic transmitter. Type in alphabetic letters just as you would on a QWERTY keyboard, and out comes a ticker tape of machine-readable Morse code. Messages could now be sent at up to 150 words per minute, a speed that would have been impossible for any manual operator of a single Morse code key.

On the receiving end of things, “a specially tuned microphonic form of amplifier” allowed messages to ring loudly throughout the station. Before, specially trained operators had to carefully listen in over headphones to often-staticky signals repeated over and over again for the sake of clarity. The act of human transduction was thus replaced by a more sensitive mechanism.

The cover of the August, 1915 issue of The Electrical Experimenter, featuring an illustration of the Sayville station. Magazineart.org

Most importantly, Sayville’s new five-hundred foot aerials “insure[d] a fluent, consistent discharge of radio wave into the air” so powerful that it only needed to be sent once. Before Sayville’s upgrade, atmospheric disturbances would produce holes in transatlantic signals. In order to ensure the reception of a complete message, transmissions were thus sent several times so that they could be cross checked on the other side. According to Sayville’s manager Dr. Karl G. Frank, the repetition of messages aroused fears of espionage. “Suspicious persons,” he complained, “were prompt to construe the process of repetition into a series of communications with German submarines.” It was his hope that such concerns would be alleviated by the more powerful, one-off transmissions.

With tangible records on paper tape, transmitted once only and ringing out clearly at the station for all to hear, the German-owned station seemed to be operating more transparently than ever at a time of increasingly strained relations with the US. Yet it would soon become clear that quite the opposite was true. Telefunken’s aspiration to so-called “absolute communication” between Sayville and Nauen in fact enabled forms of never-before-seen cryptographic deception.

We tested the plant thoroughly and after we had satisfied ourselves that it would work for at least 300 days I opened the telegraphone circuit and began to register this message to you. It will be the last one which you will receive for 30 days or more. As it must needs take us from five to 10 days to build a transmitting plant on Mars, you need not expect to hear from us for from 35 to 40 days. You might, therefore, commence to ‘listen in’ beginning with the 35th day from tonight. No message can ever be repeated, for the ‘wiping’ electromagnets of the telegraphone wipe out the magnetic impuse from the steel wire as quickly as they pass the transmitting magnets. Neither can you transmit a message to me, for no provisions were made to relay your messages to us when on Mars.

On July 7, seemingly without warning, the American government revoked the operator’s license for Sayville. That night, a force of Naval engineers and “bluejacket” sailors seized control of the plant from its German employees. Rumors surfaced that a similar takeover had been executed at the station in Tuckerton, New Jersey, which transmitted regularly to Hanover. The New York Times found that the decision to seize control of the wireless stations had been made after a series of conferences among members of President Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet.

But what had led to their decision? The official statement from the Atlantic Communication Company (which operated the plant) failed to offer answers, and speculation ran rampant. In an editorial to the August issue of Electrical Experimenter, Hugo Gernsback argued that the takeover of this powerful station was absolutely necessary since there is no telling who received its messages or how they were read. Explaining why the government didn’t seize transoceanic cable stations as well as wireless plants, he wrote:

A cable message during the time of its dispatch stays on the cable. It has only one destination; no one can “tap” the message without serious difficulties. Not so with the “wireless.” Its waves being propagated in every direction, a thousand stations, or more, if properly equipped, can catch the message anywhere within the receiving radius of the sending station.

Gernsback was right. The Germans had anticipated the possibility of a war with England and, with it, the risks of severed telegraph lines. Sayville was the answer. Thus when England actually did cut the German cables early in August 1914, Germany retained links to the outside world. Thanks to the wireless technology at Sayville, telegraphic traffic between America and Germany went on the same as before—with the difference that the messages now traveled right over the heads of Germany’s enemies.

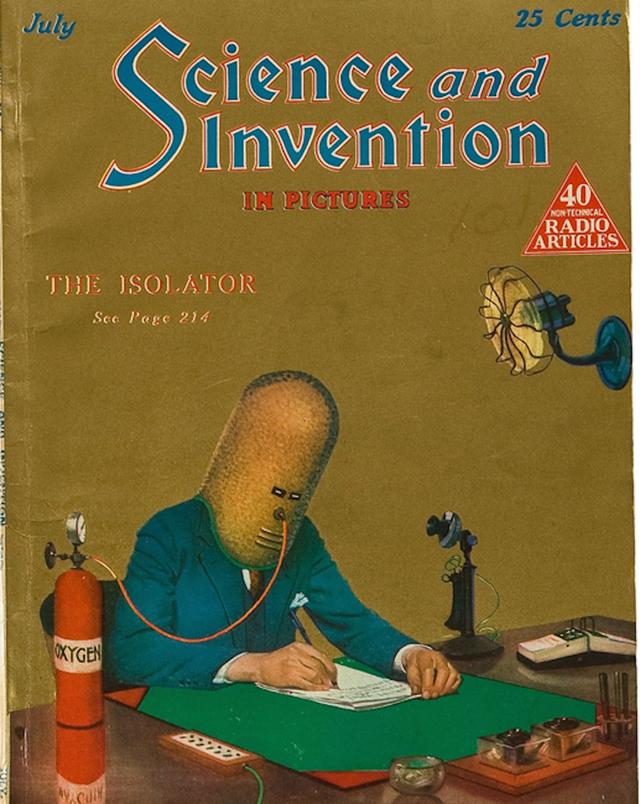

Hugo Gernsback’s “Isolator” helmet as featured on the July, 1925 issue of Science and Invention. Laughing Squid

I may add, therefore, that all conversations between Baron Münchausen and myself, which I shall publish hereafter, are exactly as stated, taken from my brother’s stenographic reports. The original notes are open to anyone doubting their truth.

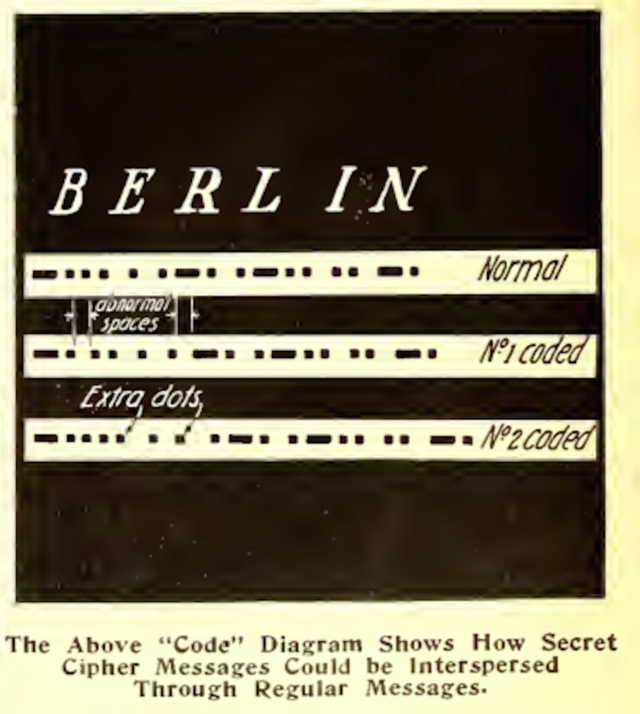

But effectively relaying these coded messages posed unique problems that demanded a new approach to cryptography. Now that the summer heat no longer troubled the Sayville plant, debates in the wireless community shifted to how lossless signals might be disguised. In one proposal, hidden instructions were interspersed within regular, ordinary-looking messages by slightly lengthening the spaces between dots and dashes (see No. 1 Coded below). Perfectly uninterrupted, strong signals meant that gaps in a message could actually mean something rather than being a product of noise or static.

Another proposed scheme involved adding additional dots to the end of normal Morse characters. Thanks to the plant’s novel keyboard-specific automation of Morse signaling, it’s possible that this overcoding could have even been mechanized through what the Electrical Experimenter called “a small attachment of an electrical nature, perhaps, which could be fitted secretly to one of the automatic paper tape perforators or to one of the magnetic key transmitting mechanisms.” Ever since the invention of the telegraph in the early nineteenth century, the cadence or rhythm characteristic of an individual telegraph operator’s sending touch was known as their “fist.” Operators were identifiable by their fist, and cryptanalysts used these unique rhythms to track patterns in the location of messages and their messengers. An automated sender could thus not only plant hidden messages within wireless signals, it would completely anonymize them.

The Navy enforced strict rules overseeing Sayville, but overlooked several glaring holes. Seeing as only four of the eighteen people working at Sayville were employees of Telefunken, there was never a moment that outgoing and incoming transmissions didn’t pass through government scrutiny. “Every message is censored before it goes out,” an article in the September, 1916 issue of the Electrical Experimenter explained. “A Government officer sits there with a blue pencil and if he suspects the message has another meaning than what is on its face he returns it to the sender; or he may paraphrase its meaning, saying the same thing in different words.” The idea was that this re-wording of the message would upset any code hidden within that precise wording—if it contained one.

What the government overlooked was that the fact that covert messages could be hidden not within the content of a given message, but rather within the signaling itself. If the speculations about an automated transcoding mechanism tucked within the Sayville sending apparatus were true, a US government employee could type out a message that contained hidden instructions to German U-Boats without even realizing it. But without a record of the transmissions themselves, only a Morse code paper tape or a transcript of the initial text, government censors didn’t have the ability to analyze the messages directly.

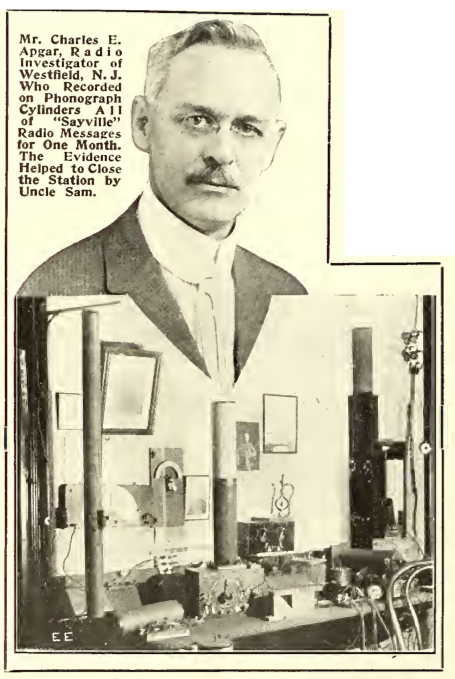

This is where an amateur experimenter named Charles E. Apgar stepped in.

The first clash with the Germans was spectacular. We rushed upon them in the early morning, but instead of our artillery using the ordinary explosive shells we used my compressed laughing gas cylinders. These were constructed in such a way that they would open upon striking the ground. The soldiers of rank and file were quipped with a similar device, who, instead of shooting bullets, shot compressed laughing gas cylinders.

Our first attack proved as great an astonishment to us as to the enemy. When we began shooting the laughing gas a the ferocious-looking Germans their expressions changed suddenly to abominable grins.

I had long since discovered that the German advance could not be stopped by ordinary means, so I adopted extraordinary measures.

Charles Apgar was a hobbyist new to the wireless scene who in 1913 had quietly devised the first ever means of recording a wireless telegraph signal on a phonograph cylinder. At some point, the US Secret Service became aware of Apgar’s tinkering and immediately understood its potential. Apgar was approached by Louis R. Krumm, the Department of Commerce’s Chief Radio Inspector about checking up on Sayville. In a profile of his work for the Secret Service, Apgar wrote,

I was called in on the matter and told to ‘get busy.’ The work of making the records began each night at 11 o’clock and continued for two or three hours, dependent on the accumulation of messages at the Sayville station. The next morning a translation of the records was made and a copy of them turned over to [Secret Service Chief William J.] Flynn, which permitted of immediate comparison with the censored message records received by other departments of the Government.

Telefunken’s Karl G. Frank was shaken by this new possibility. Upon hearing of Apgar’s recordings, Frank immediately sent out a press release: “The statement that Mr. Apgar can record messages sent out by wireless on a phonographic cylinder is hardly worth discussing. That is physically impossiblle. I haven’t ever heard of it being done. If Mr. Apgar has accomplished it he should get his idea patented and perhaps we will buy it.”

A Columbia Phonograph Company cylinder, c. 1905, similar to the one Apgar used to make his recordings. futuremuseum.co.uk

Apgar’s records allowed the government to compare the messages that were submitted for approval to the censors with the signals that actually left Sayville’s aerials. Messages that seemed to contain little more than innocent commercial transactions were found to hide instructions for German submarines throughout the Atlantic. With the simple addition of a word, a space, or a minor repetition—present neither on the text submitted to the censors nor on the ticker tape produced by the machine—covert communications could be sent right under everyone’s nose. In addition, Apgar’s recordings captured unsigned messages flashed from Nauen to Sayville, transactions that hadn’t been properly registered. Apgar’s phonograph cylinders allowed an audible record of what was actually transmitted and received by the station to be poured over and decrypted by the Secret Service.

Had the defenders found out during our advance on Berlin that we were not their compatriots they would have been powerless, as their numbers were pitifully small as compared with the immense armies of the Allies. However, they never suspected us. As we had naturally taken charge of all the telegraph and telephone lines immediately upon emerging from our forests, we sent, of course, fake war reports to Berlin all day long purporting to come from the front. The deception could not have been more complete. So you can readily see that all the ‘news’ which the Nauen wireless plant sent out broadcast each day over the entire world during the month of March was nothing but a hoax, manufactured expressly for it by our own General Staff!

When the Electrical Experimenter made public that Apgar was responsible for uncovering the station’s covert actions, he became a hero among the amateurs. An advertisement ran in the next month’s issue for the very headphones Apgar used to listen in on Sayville’s transmissions and hear that something was in fact out of the ordinary.

Meanwhile, the full extent of Karl Frank’s deception was exposed by the press. Frank’s activities as a German spy went far beyond the operation at Sayville. In August, The Providence Journal sent a formal complaint to the Secretary of the Navy, including the charge that Dr. Frank was one of the principle German secret agents in the United States. The Journal charged that he had tried, among other things, to obtain intelligence on the fire control system used by the US Navy, and to gain access to a battleship in the New York Navy Yard. Two years later, the New York Times reported that Dr. Frank was arrested at his home in Millburn, New Jersey and taken to Ellis Island, presumably for deportation.

Through the glass portholes at the bottom of the machine we could see the Marconium wires glowing in their characteristic green glow. Immediately we were lifted toward the moon overhead at a frightful speed. In less than 90 seconds the entire American continent became visible, and in a few more seconds the earth in its true form as an immense globe stood out against a pitch-black sky.

Once the full extent of the Sayville wireless spy ring became clear, public attention inevitably returned to the sinking of the Lusitania at the beginning of that very summer, in May 1915. Speculations and conspiracy theories abounded on Sayville’s role in the sinking of the ship by a German U-Boat. Were the instructions to attack sent by Sayville? How could the government have allowed the Germans to triple the station’s power in the very next month?

One popular history of the German secret service published at the tail end of the war advanced the theory that when the British admiralty received a request from the Lusitania’s Captain William Thomas Turner for protection as the ship approached the English coast, Sayville responded with duplicitous information before anyone else could. The authors of this book claimed that Sayville was able “to flash a false reply with a perfect British Admiralty touch. … The British Admiralty also received Captain Turner’s inquiry, just as the Sayville operator had snatched it from the air, and despatched an answer: orders that the Lusitania proceed to a point some 70 or 80 miles south of the Old Head of Kinsale, there to meet her convoy. Captain Turner never received that message. The British Government knows why the message was not delivered, though the fact has not, at this date, been made public.”

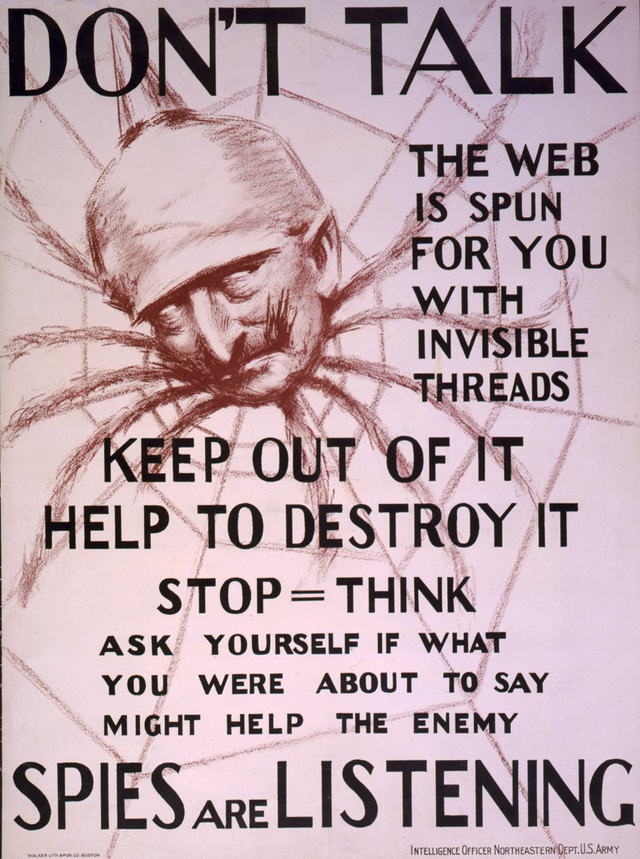

A World War One propaganda poster depicting Kaiser Wilhelm II as a spider at the center of an invisible web, c. 1918. Library of Congress

The experimenter community greeted Apgar’s decisive contribution to the war effort with great enthusiasm, holding him up as an exemplar of what a formerly closed, quirky group of amateur tinkerers could offer to the public at large. But it was Apgar’s discovery of the inherent insecurity of the airwaves that led several American congressmen to draw up legislation that would ban all amateur radio activities. Citing security concerns, the Navy took control of the airwaves for the remainder of the Great War. Once it was over, they didn’t want to give it back, setting up one of the first battles over public and private interests in broadcast regulation. The Alexander Wireless Bill, though it never passed, is a reminder today of the close connections between state secrets and amateur eavesdropping.

Today, the word “cable” has become synonymous with encrypted diplomatic communications—like those included in the famed Wikileaks documents—despite the fact that these messages are now sent via e-mail. The story of Sayville serves as a reminder that wireless technology, from its inception, involved a delicate negotiation between state security, secrecy, and citizen oversight.

But I note by my chronometer that the time is up and in a few seconds the telegraphone wire on my radiotomatic on the moon will be to full capacity. So I must cut off short. Au revoir dear boy, and pleasant dreams till to-morrow…’ A low rhythmic hum for a few seconds, then click, click-click, click- click-click, click, a snapping sound and the ether between the Moon and old mother Earth was undisturbed once more.

Further reading:

The Electrical Experimenter digitized on Archive.org