There’s a Starman / Waiting in the Sky: Yuri Gagarin sings!

What to hum to the cosmos? Surrounded by uncaring vacuum, what to whistle in the dark?

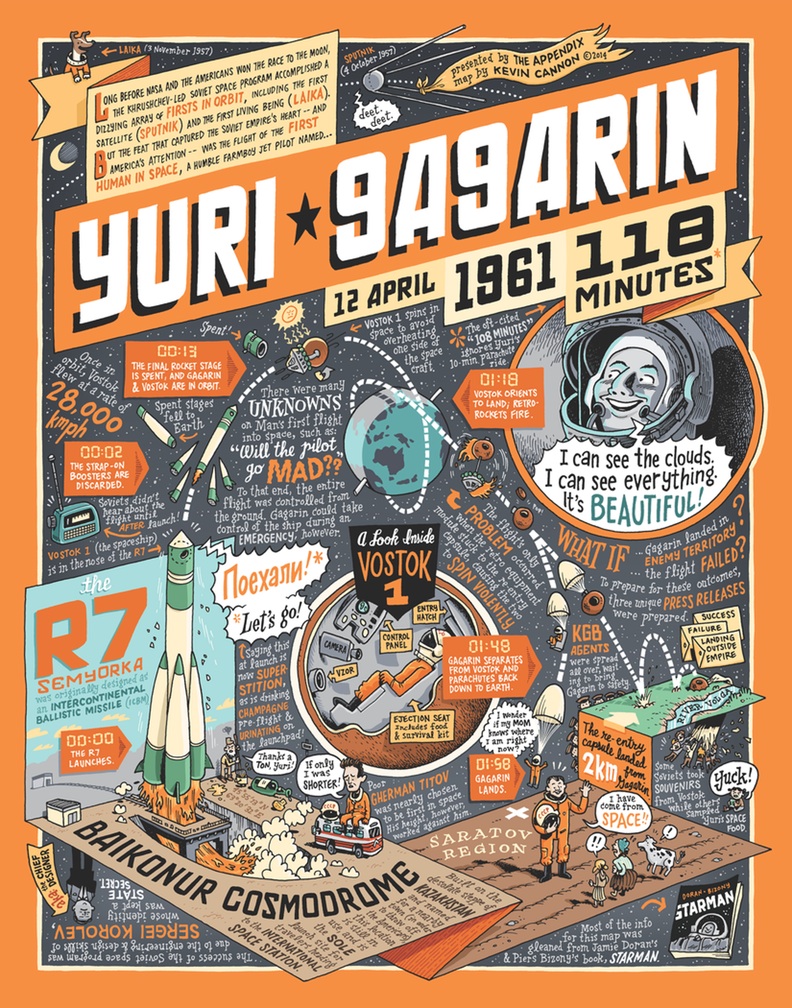

Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space, had time to decide. On April 12, 1961, while waiting on the launch pad in Kazakhstan to take off for his pioneering orbit around Earth in the spacecraft Vostok—depicted wonderfully in this issue’s carto-biography by Kevin Cannon—the twenty-seven year-old learned that a minor problem had caused a six-minute delay. His cosmonaut comrade Pavel Popovich worried Gagarin might get restless during the wait; during his pre-flight medical exam Yuri had been pale and quiet, and had sometimes started humming songs. To keep him from getting “bored,” Popovich went to see about piping some music over the radio. A few minutes later, Sergei Korolev, the father of the Soviet Union’s space program, asked if Gagarin could hear it.

“Nothing yet,” Gagarin replied.

“Of course, that’s the way musicians are,” said Korolev. “Now they’re here, now they’re there, but they don’t do anything fast, as the saying goes, Yuri Alekseyevich.”

On came the music.

“Oh, now they’ve done it,” Gagarin said. “They gave me love songs.”

“A love song? Good choice, I’d say, Yuri.”

Popovich came back on the line. “Yuri, they gave you the music, right?”

“They gave me the music, all is well.”

“Well, well, now you won’t be so bored.”

Half an hour passed. Gagarin stayed cheerful. He kept his heart rate at sixty-four beats per minute. The music was presumably cut by the time mission control told him to turn his volume up to loud. As 0906 hours turned to 0907 hours, in kicked the ignition.

“POYEKHALI!” Gagarin shouted. Off we go!

Humanity, shaking hands with the cosmos. Weightlessness, before Kubrick’s 2001 made Strauss’s ‘Blue Danube Waltz’ its soundtrack. Gagarin, the first man to see two dawns on one day.

The flight lasted 108 minutes. For ten of them near the end, the capsule failed to separate from the instrument module, and Gagarin spun on three axes. The capsule separated, righted, and flames began to lick its sides. It was then, perhaps, that Gagarin began to sing or whistle—or so he later told Nikita Khruschev—a tune by Dmitri Shostakovich.

“The Motherland hears, the Motherland knows/Where her son flies in the sky!”

Seven kilometers above the ground, Gagarin was ejected from the spacecraft, presumably no longer singing. He landed in Siberia, assured a farmer and her daughter that he too was a Soviet, and went to find a phone to call Moscow.

Back home, Yuri’s sister Zoya waited nervously for reports on the radio. The cheerful patriotic music stopped, and it was announced that Gagarin had been enrolled in the Komsomol Central Committee Roll of Honour. Zoya thought it was a prelude to announcing his death.

It was not. That moment would come seven years in the future, during a training accident. When the music returned in 1961, Zoya took heart that Yuri was safe.

The above exchange draws from three translations: this awkwardly translated transcript of the launch; Asif A. Siddiq, Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974 (Washington, D.C.: Nasa History Division, 2000), 276, and Jamie Doran and Piers Bizony, Starman: The Truth Behind the Legend of Yuri Gagarin (New York: Walker & Company, 2011), 101. Some space historians have raised red flags about some aspects of Starman, particularly its reliance on one ex-KGB source, but for this sequence—and the sequence of events rendered in Kevin Cannon’s narrative—it flies.