Controlling Sound: Musical Torture from the Shoah to Guantánamo

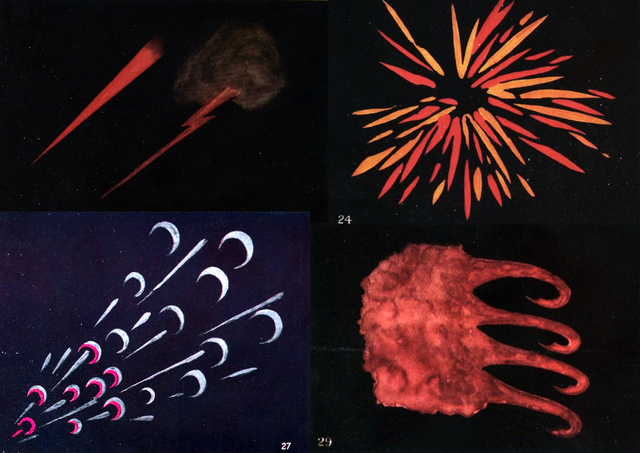

“Sustained Anger,” “Explosive Anger,” “Greed,” and “Fear,” by the synesthetic artist Annie Besant, 1901. Wikimedia Commons

“Purely physical torture is losing importance,” observed the psychologist Gustav Keller in 1981. “Psychological and psychiatric findings and methods are taking its place, planned and sometimes administered by white-collar torturers.” This statement, though prescient, is debatable: plenty of purely physical torture has been reported by former prisoners of Guantánamo and Bagram. The implication, however, is one of progress: that torture has been civilized, professionalized, in some way stripped of its teeth.

After the news broke that American soldiers were torturing detainees in secret prisons like Guantánamo, the idea spread that so-called “no touch” torture is more humane than more conventional methods involving violence to the body. No-touch torture utilizes methods like sleep deprivation, temperature regulation, violation of cultural and religious taboos, the playing of loud music, and psychological manipulation while interrogating prisoners. These methods, though often brutal, frequently don’t leave physical marks, thus nebulizing the concept of torture and leaving the act more open to interpretation.

Music torture at Guantánamo is a prime example of this mindset. Endless news cycles discussed whether waterboarding, hooding, and playing loud music could even be considered torture. Musicians, when asked for comment about “music torture”, sometimes responded dismissively: Metallica’s James Hetfield replied to the news with the comment, “We’ve been punishing our parents, our wives, our loved ones with this music for ever. Why should the Iraqis be any different?” Bob Singleton, who composed the often-used Barney the Purple Dinosaur theme song, wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Would it annoy them? Perhaps … But could it ‘break’ the mental state of an adult? If so, that would say more about their mental state than about the music.”

The implication that these torture methods are somehow softer or easier to withstand than traditional methods is an interesting but dangerous fallacy. In no-touch torture, the torture weapon is the prisoner’s own body, which aches in stress positions, shivers, sweats, and demands sleep. The body itself becomes the enemy, psychologically destroying the prisoner from the inside out.

During war-crime trials, the torture weapon is often used as a synecdoche for the torture itself: a hammer, thumbscrew, or bathtub presented as evidence manifest the experience of that torture in an object. But with no-touch torture, where the weapon is the prisoner’s body, no such object exists to display as a remnant of the event. In the absence of a clearly identifiable torture weapon, the torture practiced on a prisoner becomes nearly invisible to outsiders, and the room itself becomes toxic for the victim.

As a physical torture, music is rarely used by itself; instead, it’s a component of the toxic environment. By blasting music, blaring lights, and keeping a cell ice cold, a prisoner is prevented from sleeping, and this deprivation is the ostensible goal. After enough of this treatment, prisoners are apparently easier to interrogate. As Sergeant Mark Hadsell of the 361st PsyOps Company in Iraq explained in 2003,

These people haven’t heard heavy metal. They can’t take it. If you play it for 24 hours, your brain and body functions start to slide, your train of thought slows down and your will is broken. That’s when we come in and talk to them.

Beyond its psychological power, music’s physical properties also mean that it can be used as a weapon by itself. The US has used LRADs and infrasonic weapons, causing reports of blown out eardrums, dizziness, ringing, and temporary deafness. ‘Safe’ levels of sound are articulated in scientific language.

In Guantánamo, music’s physical and psychological properties interrelate. Not only does the music cause headaches and sound like loud, painful banging, its aesthetic qualities demand an innate human reaction. When we listen to music repeatedly, it inscribes itself in our brains (think of ‘getting a tune stuck in your head’ or a German ‘Ohrwurm’).

Musicologist Christian Grüny writes about a former prisoner of Guantanamo who was tortured with David Grey’s “Babylon,” a soft rock ballad seemingly chosen for the geographical coincidence (Babylon as a location in the Middle East). Years after his torture, when Grüny played a part of the song for him, he immediately burst into sobs. Suzanne Cusick describes how music’s cultural connotations come to symbolize the military power of the torturer. Because of music’s ability to get inside its listener, musical torture represents “the overwhelmingly diffuse Power that is outside one, but also is inside, and that operates by forcing one to comply against one’s will, against one’s interests, because there is no way, not even a retreat into interiority—to escape the pain.”

How do interrogators choose the soundtracks of musical torture? During the siege of Fallujah in November 2004, the 361st PsyOps company bombed the city with Metallica. As PsyOps spokesman Ben Abel explained at the time:

It’s not the music so much as the sound. It’s like throwing a smoke bomb. The aim is to disorient and confuse the enemy to gain a tactical advantage … our guys have been getting really creative in finding sounds they think would make the enemy upset …These guys have their own mini-disc players, with their own music, plus hundreds of downloaded sounds. It’s kind of personal preference how they choose the songs. We’ve got very young guys making these decisions.

During the siege of Fallujah, mullahs responded to American rap with “loudspeakers hooked to generators, trying to drown out Eminem with prayers, chants of Allahu Akbar, and Arabic music.”

In the course of my doctoral research, I’ve had the chance to reflect on the parallels between these news stories and the long history of musical torture. The other half of my project involves mapping some of the music heard in the infamous Nazi concentration camp Auschwitz. In some ways, the projects are so different as to seem unconnected: music played at Auschwitz was part of an overall culture of terror and control, but not a torture in itself. However, the same idea, that musical space is a metaphor for control, can be seen all over the camp. A particularly clear example can be heard in the hospital barracks at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

A map of the sonic environment at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp in 1943. Melissa Kagen and Jake Melrose, 2012

Szymon Laks, a survivor who was forced to play in the camp orchestra, describes how his ensemble was sent to the barracks on Christmas of 1943 to console the sick with carols, specifically “Stille Nacht” (“Silent Night”):

After a few bars quiet weeping began to be heard from all sides, which became louder as we played and finally burst out in general uncontrolled sobbing. I didn’t know what to do. To play on? Louder? From all sides, spasmodic cries began to roll in on me. ‘Enough of this! Stop! Clear out! Let us die in peace!’

Laks, though a prisoner himself, appears here as a representative of Nazi power, simply because he’s playing Christmas carols to dying (largely Jewish) inmates.

Stille Nacht (Silent Night)

The prisoners wished to die in peace—which is to say, they wanted the barest hint of autonomy over the space in which they die. This music, to which they are forced to listen, disturbs them not only because it disrupts that space, but because it invades their bodies. A piece played inside a brick barrack would be audible on the path outside, and the march played next to the path would be audible to anyone within. Moreover, there is a limited distinction between sounds heard by guards and sounds heard by prisoners—a difference in psychological affect, certainly, but not in the music itself.

In other words, the sounds heard by guards and prisoners were often the same and, in this strange sense, prisoners and guards were and are united in their experience. In the case of musical torture during the war on terror, this sharing was, at least in one instance, more radical. Jonathan Pieslak records the following quote from U.S. soldier C.J. Grisham, who used music during interrogations in Iraq:

As long as they were listening to babies crying, I had to listen to babies crying …You are not allowed to do anything to the enemy, by law, that you wouldn’t do yourself. So if I’m getting eight hours of sleep, the people I’m interrogating have to get eight hours of sleep, if I’m only getting two hours of sleep, then my prisoners are only required to get two hours of sleep. We can’t treat them any worse than we treat ourselves.

This inference of shared experience through music is reminiscent of the musical warfare at the Siege of Fallujah, where opposing soundtracks competed for control of the city in a sonic analogue to the battle. It also articulates the sonic hegemony I’m investigating: how sound equalizes all ears, while still demonstrating an unequal power relation.

Grisham’s description of this army guideline, requiring a certain equality between prisoners and guards, provides an interesting inversion of a traditional understanding of torture. For Scarry, torture’s premise is the utter gulf between a person being tortured, who experiences the pain as world-destroying, and a person not being tortured, who doubts the existence of that pain because of its utter unsharability. The boundaries between torturer and victim blur—not in their power relations, but in the similarity of their experienced environment.

That shared environment is part of what I find so interesting about music in Auschwitz, and it is a feature of the camps that I have tried to visualize in my work. My partner Jake Melrose and I mapped forced music (which prisoners were required to play) in red, and voluntary music in blue. Performance allowed for a modicum of creative expression, an outlet not readily available for manual laborers. For example, after a rehearsal in Block 24 of Auschwitz I (the Main Camp), a Hungarian pianist played Chopin’s Funeral March (Piano Sonata #2 in B-flat minor), saying it was the only appropriate music considering the circumstances. This same Block 24, however, transformed into a perverse jazz club when SS officers came to unwind after a long day. They would ask musicians to play prohibited American jazz and ragtime songs like “Dinah,” “Sweet Sue,” “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love,” and “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.”

Alexander’s Ragtime Band

Directly outside Block 24 was the area through which work gangs marched into and out of the gates, accompanied by various marches like Fucik’s “Florentiner Marsch,” Liebling’s “Wenn Ich Traurig Bin,” and the “Horst Wessel Lied.” Obviously, this area could become a very different musical environment at different times of the day. By having the freedom to choose the music they wanted to hear, the guards made their authority clear and their control absolute. Moments of musical mourning, like the pianist playing Chopin, had to be squeezed in when no one was listening.

Chopin’s Piano Sonata #2 In B Flat Minor, Op. 35, “Funeral March”

Julius Fucik’s Florentiner Marsch

Music played in Guantánamo is similarly varied. The most confusing category to me is emotional, nostalgic music: Fleetwood Mac, Matchbox 20, Chris Christopherson, David Grey’s “Babylon” as well as children’s songs—notably the themes from Sesame Street and Barney the Purple Dinosaur. To me, this bespeaks a strange nostalgia for a specifically American childhood, even as those American children have grown up to inherit a world that is nothing like what they anticipated while watching Sesame Street.

“American Pie,” another song in this category, similarly invokes nostalgia for a lost past, in addition to carrying a religious implication—one verse reads, “the three men I admired most, the father, son, and holy ghost, they caught the last train to the coast, the day the music died”—in a kind of requiem for a nation that’s strayed from its God. The emotional thrust of this piece would hit American soldiers much harder than prisoners less familiar with Americana. This is a particularly American kind of abuse: aggressive exertion of cultural hegemony mixed with physical force, ostensible compliance with the “good guy” rules, and nostalgia for the lost American dream.

My project began as an attempt to think about music in space. How does music work to control space, and how can it affect bodies inhabiting that space? What does an environment that has been saturated with an enemy culture’s music sound like, and is the music functioning as anything beyond cultural aggression?

But one of the most interesting aspects for me, beyond those initial questions, has been the responses. The first comment from almost everyone who hears about my project is either a joke or a respectful “hmm,” depending on which case I begin with. If I start to describe music torture in Guantánamo, the comment will usually be a quip about what musical genre or artist they would consider torturous: country music, Yoko Ono, Justin Bieber, insert-hated-group-here. If I begin by describing the Auschwitz maps, the comment is something quiet, curious and respectful. It seems like firsthand evidence of the way we differentiate history from current events, and American behavior from everyone else’s.

And this American exceptionalism can prevent us from hearing crucial voices coming out of Guantánamo now. An op-ed in The New York Times on Sunday, April 14, 2013 by Samir Naji al Hasan Moqbel reported on a hunger strike in Guantánamo. It ended with the plea, “I just hope that because of the pain we are suffering, the eyes of the world will once again look to Guantánamo before it is too late.”