Deadly Notes: Atlantic Soundscapes and the Writing of the Middle Passage

“A Kind of Chorus”

[S]ince speech was forbidden, slaves camouflaged the word under the provocative intensity of the scream. No one could translate the meaning of what seemed to be nothing but a shout. It was taken to be nothing but the call of a wild animal. This is how dispossessed man organized his speech by weaving it into the apparently meaningless texture of extreme noise.

—Edouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays

In Herman Melville’s Benito Cereno, the captain and crew of the Massachusetts-bound Bachelor’s Delight anchor their ship in the harbor of a small, uninhabited island off the coast of Chile. They soon find that they are not alone. When a rather battered and weather-beaten Spanish merchant ship sails into harbor, the American captain, Amasa Delano, decides to approach the vessel and offer his services.

Boarding the San Dominick, Delano is immediately struck by the “the wailing ejaculations of the indiscriminate multitude” and the “noisy confusion” resonating throughout the Spanish ship: oakum pickers “accompanied the[ir] task with a continuous, low, monotonous chant, droning and drilling away like so many gray-headed bag-pipers playing a funeral march.” Hatchet sharpeners “clashed their hatchets together, like cymbals, with a barbarous din.” Growing “impatient of the hubbub of voices,” Delano turns to the captain of the ship, Benito Cereno, and asks him to account for the discord. As Cereno tells how sickness and maritime misadventure depleted the crew and battered the ship, the “cymballing of the hatchet-polishers” continues to punctuate the narrative, and Delano wonders why “why such an interruption should be allowed, especially in that part of the ship, and in the ears of an invalid.”

Observing the apparent lack of order on board the San Dominick with his “blunt-thinking American eyes,” Captain Delano perhaps serves as a cautionary tale for “bad readers.” By refusing to recognize the “noisy confusion” as a mode of communication, Delano fails to read—or, more accurately, to hear—what has actually happened on the ship: the enslaved men and women had risen up against their former captors, had taken control of the ship, and were attempting to sail to Senegal. The apparent disorder was, in fact, not disorder at all: rather it was a highly orchestrated “operatic” performance that staged the relationship between free and enslaved—European and New World African—precisely as Delano expected to see it.

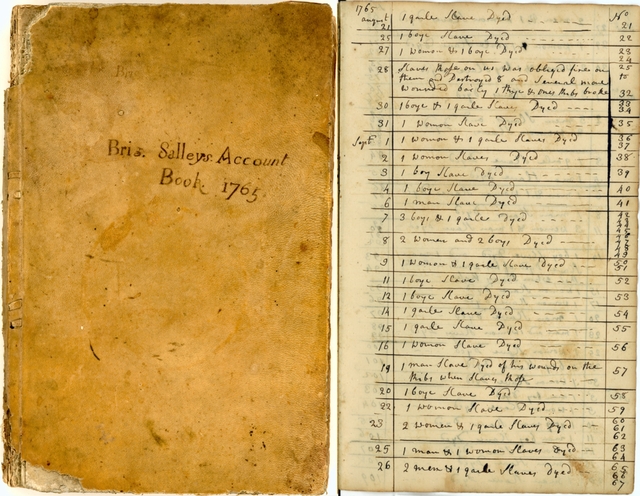

I begin with Melville’s novella because it may also caution scholars who study the archives of Atlantic slavery. Inevitably, we too, like Captain Delano, view the contents of ship’s logs, captain’s journals, and account books with “a stranger’s eyes.” The cold empiricism of these records encourages us to read at a surface level and glean only the facts that record keepers intended to be found.

Yet ships traveling the pathways of the Middle Passage—and beyond—were anything but silent spaces. In the words of a sailor on board the Liverpool slave trader, the Hubridas, in 1786, enslaved men and women raised their voices in “a kind of chorus” that resounded “at the close of particular sentences.” The sailor’s use of the term “chorus” is worth noting. A chorus consists of individual voices coming together to produce a collective, synchronized voice, and in theatrical traditions the chorus served as commentary on dramatic action. These call and response soundings allowed men and women speaking different languages to communicate about the conditions of their captivity. In fact, on board the Hubridas, what began as murmurs and morphed into song erupted before long into the shouts and cries of coordinated revolt. In the words of another sailor, “what [was] the subject of their songs [I] cannot say.”

However, as readers of these archives, we can begin to imagine. It is no easy task to reconstruct these Atlantic soundscapes: sound fades, only writing remains. At the surface, the slave trade’s systematic documentation—in the form of ship’s logs, insurance documents, sales records, account books, and published journals—appears to record the erasure and suppression of African voices, cultures, and resistance. But, like Captain Delano, I wonder if there may be something in these records that we have failed to hear. By understanding the writing of the Middle Passage as an early audio technology—rather than simply a history of exploitation—we can think about sound as a new language of resistance perhaps particular to pathways of the Middle Passage and embedded in the writing itself. In these accounts the deadly notes of an enslaved cargo communicating and acting in mass regularly interrupt the deadly marks of the official record. Maritime writing thus records the conditions of the Middle Passage from two perspectives: the calculated master narrative at the surface of the record, and the sounds that erupt from the depths.

The account Book of the Brig Sally with a 1765 page from its inventories listing slaves. Digitized by the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

Histories Sunk in the Sea

By a curious coincidence, as each point was recalled, the black wizards of Ashantee would strike up with their hatchets, as in ominous comment on the white stranger’s thoughts.

—Herman Melville, Benito Cereno

Because few firsthand narratives of the Middle Passage written or dictated by New World Africans survive, the experiences of men and women traversing the Atlantic has been understood as largely unrepresentable. For these reasons we inevitably turn to the records of their captors, and this record seems to only confirm the unrepresentable nature of enslaved voices and experiences: the sounds produced by captives are recorded as mere noise—as ‘murmurs,’ ‘cries,’ ‘complaints,’ ‘shrieks,’ ‘groans,’ ‘bursts,’ ‘uproars.’

By favoring the written word, we also thereby privilege forms of knowledge deriving from sight rather than sound. Sight has long been associated with ‘reason’ and modernity, in turn, as triggered by and indebted to the rise of ocular thinking. And as we ‘examine,’ ‘look to,’ ‘investigate,’ and ‘seek’ the remnants of histories sunk in the sea, the very language we use to disclose, discover, and detect the meanings of texts points to a methodology that is, in many ways, still rooted in Enlightenment-era empiricism and traditions of favoring sight as the most critical of the five senses.

The rise of “sound studies” has challenged the primacy of text and has invited us to think about—or listen for—how sound has shaped the history of human experience. By focusing on the sounds we can glean from written records, we can begin to listen to the static—or silence—and for other messages embedded in the texts. And it is here that the cold accounts of the slave trade itself become the background static—the non-sense—that frames the primary action staged on slave ships: that is, enslaved people’s acts of communication and production of sounds.

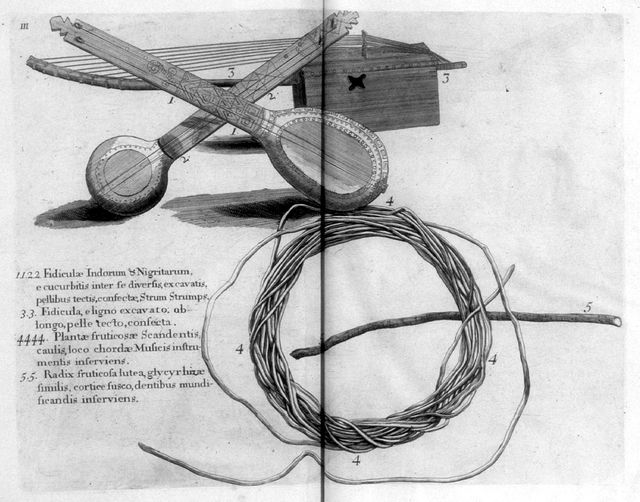

The soundscape of the Middle Passage relied on the human voice, the body, and the ship—rather than traditional instruments—to make sound. Notably, these sounds are produced by people using the material conditions of their imprisonment—instruments of labor, chains, and the ship itself. The captain of the Sandown, for instance, records feet stomping on boards, hands slapping on thighs and, what seemed to him “unintelligible cries.” Dr. Thomas Trotter, a surgeon on board the Brookes recreates the stifled voices crying out from below deck, “Yarra! Yarra!” [We are sick] and “Kickeraboo! Kickeraboo!” [we are dying]. And Joseph Hawkins dramatizes voices and bodies staged for revolt as enslaved men and women in the hold “set up a scream,” “shouting whenever those above did any thing that appeared likely” to overturn the order of the ship.

One of the earliest images of the gourd banjo, an instrument of the Middle Passage and African diaspora, depicted in Sir Hans Sloane’s Voyage (1707). Wikimedia Commons

By using their own bodies to make sound, enslaved Africans could contest the logic of their enslavement, challenging the very notion that these bodies are no longer their own. The acoustic architecture of ships was essential to creating this sound. In Olaudah Equiano’s account of the Middle Passage he describes the ship as a “hollow place.” As Equiano’s language suggests, the grave-like architectural design of the ship and its daily workings were intended to strip men and women of ties to culture, language, and homeland, and to alienate them from each other; however, these very conditions may have led to the formation of new communities and new cultures.

The very hollowness of the ship, structured by wood, cloth, and copper, meant it was also a space that was, if unintentionally, designed to resonate and carry sound: wooden ships were gigantic, migrating percussionist instruments that carried voices, rhythms, and sounds beyond ship holds and deck barricades. Moreover, if sailors and captains used the spatial design and knowledge of ship mechanics to assert Anglophone authority, enslaved men and women may have used the ship as percussionist instrument and amplifier of sound to contest that authority.

While the nature and goal of commercial maritime writing means these sounds are rare in the records, they are a significant characteristic of enslaved peoples’ accounts of the Middle Passage. For instance, in Ottobah Cugoano’s 1787 narrative, he recounts “when a vessel arrived to conduct us away to the ship, it was a most horrible scene; there was nothing to be heard but the rattling of chains, smacking of whips, and the groans and cries of our fellow-men.” The “horrible scene” in Cugoano’s account quickly shifts registers to the sounds of the ship, and thus from the visual to the auditory: chains rattling, whips lashing. Cugoano repeatedly acknowledges that these experiences are beyond what “language can describe,” and his passage into slavery also suggests a passage into an Atlantic soundscape defined by the voices of the enslaved—rather than the written record of captors.

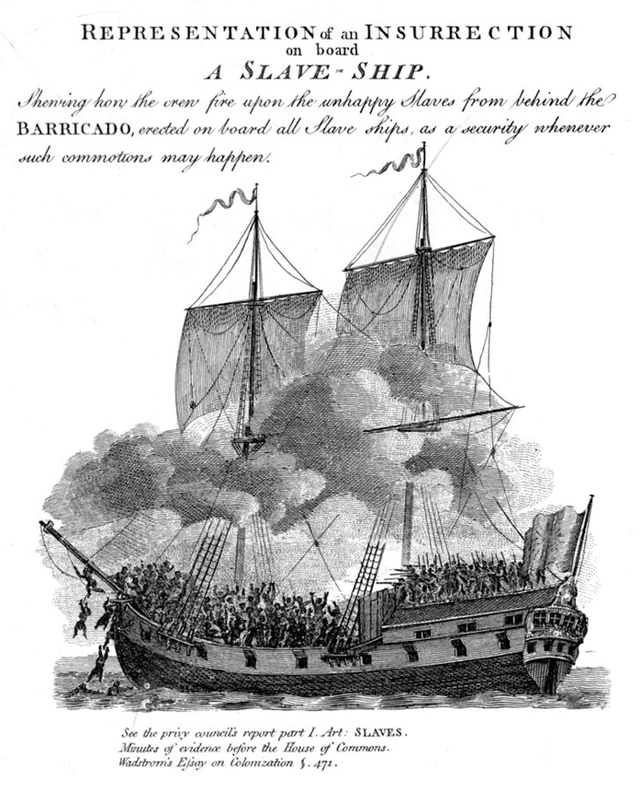

As Paul Gilroy suggests, the “unsayability” of racial terror “can be used to challenge the privileged conception of both language and writing as preeminent expressions of human consciousness.” Language and writing have only a “limited expressive power” to communicate the polyphonic—or multi-sounded—experiences of the Middle Passage. Sound, in the words of Saidiya Hartman, could be said to “topple the hierarchy of discourse, and … engulf authorized speech in the clash of voices”—or, as in Benito Cereno, the clash of hatchets. That is, the sound produced by New World Africans may represent a counterclaim to political enfranchisement and may provide another model of political process. The combined record of noise and revolt suggests that cargoes of captive men and women speaking a number of different languages and dialects who began their journey to ships coasting off the shores of Western Africa from vastly different regions and cultures began to communicate with each other and to act en masse.

In the words of another author, the poet James Field Stanfield, “fearful sounds,” “deadly notes,” and “trembling rage” reverberate through the bodies of slaving ships. He continues, “In one long groan the feeble throng unite; One strain of anguish wastes the lengthen’d night.” Out of discordant voices, he suggests, emerge sounds that combine in a polyphonic chorus to contest the abstraction and inhumanity of the slave trade. These sonic registers transform radical unbelonging into, potentially, a form of radical resistance—radical, perhaps, precisely because it cannot be reproduced by the record.

“Representation of an Insurrection on board a Slave-Ship,” from Carl B. Wadstrom, An Essay on Colonization (1794). Slaveryimages.org, compiled by Jerome Handler and Michael Tuite, and sponsored by the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and the University of Virginia Library.

Now with scales dropped from his eyes, [Captain Delano] saw the negroes, not in misrule, not in tumult, not as if frantically concerned for Don Benito, but with mask torn away, flourishing hatchets and knives, in ferocious piratical revolt.

—Herman Melville, Benito Cereno

New ways of reading the archive of Atlantic slavery are particularly significant at this moment. Since 2002, eight major cities—Berkeley, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Oakland, Philadelphia, and San Francisco—and three states—California, Iowa, and Illinois—have passed slavery disclosure laws. Disclosure laws belong to a history of movements to secure reparations for slavery: they require companies to research and then disclose any ties that these companies or their predecessors had to slavery. The focus on disclosure—on opening up that which was closed or shut, on unclosing, unfolding, and unfastening contemporary economic and historical ties to the slave trade—points to a history that will not be silenced.

Yet the question remains: whose stories do these archives tell? How can one represent the (largely) unvoiced experiences of men and women on ships traversing the Middle Passage? And can this be a story of their voices and resistance, or merely a repetition of historical violence by re-examining the cold accounting of the written record? Maritime writing may be produced by Europeans, but it also reminds us that enslaved peoples formed a significant part of an emergent soundscape of modernity. Technologies of seeing and looking serve as imperial engines that perhaps only sound can contest.

In accounts that record the sounds of insurrection along the routes of colonial slavery, we can see—and listen for—histories sunk in the sea.