Listening to the Past: An African-American Lullaby

My research tries to capture the sounds of the past before the advent of recorded music. I’m curious about ideas that were spoken and sung and shouted and strummed, focusing particularly on musical sounds produced by Afro-Atlantic people in the long eighteenth century. A few of these sounds were transcribed into dots and lines on paper. The descendants of others survive in thriving contemporary music genres. These imprints contain clues about the sounds that weren’t so lucky.

The musical expression of early musicians has not been entirely lost; much of it has been preserved or resurrected in a variety of print and performance-based archives that are available for study. In my work, I question the primacy of documents in the pursuit of knowledge about the sonic past and show that our conventional modes of study can make it difficult to explore aural culture through textual records.

In what follows I share an experimental encounter with a particular song that found its way before my eyes and into my ears. It is not the perfect object through which to answer my questions about the musical life of Afro-descendant people in the Americas, but this little lullaby taught me something about how to hear the past.

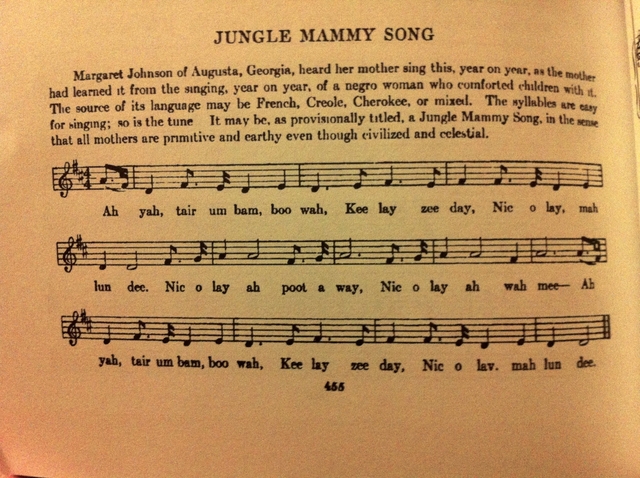

“Jungle Mammy Song”—a cringe-worthy title if ever there was one. The transcription provided by Carl Sandburg in his collection of folk music, American Songbag (1927) explains:

Margaret Johnson of Augusta, Georgia, heard her mother sing this, year on year, as the mother had learned it from singing, year on year, of a negro woman who comforted children with it. The source of its language may be French, Creole, Cherokee, or mixed. The syllables are easy for singing; so is the tune. It may be, as provisionally titled, a Jungle Mammy Song, in the sense that all mothers are primitive and earthly even though civilized and celestial.

The compiler, though most famous for his work as a poet and a biographer of Abraham Lincoln, was a musician and avid song-collector. His American Songbag was published during an era in which fascinations with blackface minstrelsy and “coon songs” were giving way to more folkloric presentations of American musical forms. The book offers arrangements of many different kinds of music, including cowboy songs, work songs from railroads and logging camps, and a sizable number of pieces emanating from the black experience.

In the volume, Sandburg’s appreciation of African-American music competes with his choice to refurbish long-standing stereotypes about “mammies” and render song lyrics in “negro dialect.” The Songbag is no outlier in this regard. It has long been common for white authors to denigrate and laud black music culture in the same breath. Many of the earliest accounts of Afro-Atlantic musical practices include this type of reckless and self-important ambivalence. Seemingly uncomfortable with all that the term “jungle mammy” implies, Sandburg wades into sexist territory while addressing the derogatory title by reassuring readers that “all mothers are primitive and earthly even though civilized and celestial.”

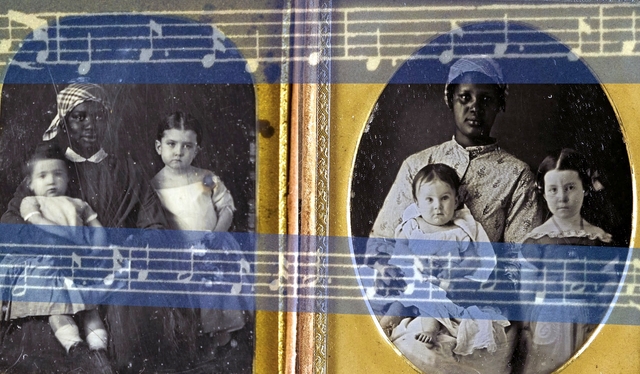

Both during slavery and after, the power structures of American society confined many black women to the role of caretakers of white families—creating a legacy of close yet troubled relations between black nurses and white children. In addition to the “mammy” stereotype, this arrangement has long been romanticized and idealized in literature and images emerging from white perspectives, particularly in the South. But rather than focusing strictly on the ways in which the image of the “negro woman” who sang this tune was degraded in Sandburg’s introduction and attending cultural norms, I want to ask whether this imperfect, highly mediated artifact bears witness to her experience, history, and voice. If we can mute the iconography of The Black Mammy, what might we hear?

Because we do not know much about the woman who is said to have comforted children with this song, it is difficult to imagine the contours of her life, much less the timbre of her voice. We are left to wonder many things like, did she work as a nurse and if so, how did she feel about her job? Did she sing this song to her own children? What other musical practices did she participate in? As a researcher, I would love to verify that the song was originally authored or transmitted by a newly enslaved person or from an established slave culture, since both scenarios would strengthen the song’s ties to early Afro-diasporic musical practices. Whatever the case may be, the musical transcription is a rare artifact because it connects listeners to the artistry of a female singer whose musical expression would otherwise be lost to us.

Though little is clear about the vocalist’s biography, we do know something about the way her song was circulated. She is said to have “comforted children” with it and Margaret Johnson’s mother appears to have done the same, transmitting the piece across at least three generations as it was sung “year on year.”

I am curious about why the music made such a strong impression on those who encountered it. Perhaps the original singer had an especially beautiful voice or an especially beautiful way with children. Maybe she sang it passionately to honor the memory of a particular child who had loved the piece—a first born or a dear younger sister. Or alternatively, perhaps she invented the song to shush fussy white children with a supposedly “authentic negro” lullaby as a kind of joke or a subtle act of resistance. Or the tune could have entered Sandburg’s Songbag simply because it is catchy and easy to remember.

Whatever the original inspirations for the melody might have been, the history of its circulation is a testimony to its resonance with listeners. It endures, year on year.

The song is so resonant, in fact, that it found its way from Sandburg’s page into my voice—and from there, into the voices of a new generation. When I first thumbed my way through the facsimile of American Songbag that my mother had ordered for me over the Internet on a whim, “Jungle Mammy Song” immediately caught my eye. At first disgusted by the title, I was then intrigued by the headnote and even more so by the undecipherable lyrics. I wanted to learn it so that I could hear it, hoping that it would yield some sonic information about the early music cultures I study. I also wondered if the music-making would be able to drown out Sandburg’s disrespectful story-telling.

Learning the song was a process of creation as well as discovery. At first using a mandolin to pluck out the notes, I learned the melody and finally the words—an interesting task because the unfamiliar language required a lot of guesswork. In addition to selecting a key, note values, and time-signature, the arranger took it upon themselves to punctuate the words in the same way that they would familiar syntax. Lyrics are often accompanied by dashes and commas that indicate the manner in which they should be expressed musically.

It seems bizarre to do this to an unknown language, but the directions helped me to deliver word-strings as musical phrases. The arranger probably followed the musical line when deciding how to punctuate the lyrics, rather than the other way around. Here is a recording of one of my early attempts to render the song:

The author shares an early attempt to render the lullaby.

I immediately enjoyed singing the melody and especially the expressive first words, “Ah yah.” The relaxed, open syllables and the descending notes feel quite a bit like sighing. Though I love the way the song feels in my voice, I am not entirely taken with my musical interpretation. In the recording you will notice that my vocal style is informed by classical singing and that I use a vibrato and a clear “attack” in my pronunciation. By that I mean that the syllables are not obscured by elision and the initial parts of words and notes are articulated more forcefully than they might be in other traditions.

When I learn music by reading, I find it difficult not to perform in the conventions of my classical training; much as a long-dormant accent emerges when I go home to my native East Texas. Context is everything. By contrast, in my activities as a bluegrass fiddler, I learn primarily by ear. Bluegrass is one of many music traditions that prides itself on a dependence on aural transmission. When I learn a fiddle tune, or a vocal melody by ear, I find it much easier to be expressive in my initial interpretations. To be sure, many classically trained musicians have a deft facility with sheet music and can perform it with far greater flexibility.

I bring up issues of acquisition and style because they are uniquely challenging when singing (or transcribing) for historical purposes. Because I study an early oral music culture in which there are very few transcriptions and no audio-recordings, I am interested in gleaning whatever information I can from sources that might otherwise seem only distantly connected to earlier centuries. It is so rare to find an example of women’s music from this period, and I wanted to do this song and its original performer justice. But I felt inhibited by my performance style and frustrated that I would never be able to really know how the woman who popularized this song would have sung it. Because my interest is in vernacular music and its aural circulation, it felt odd to encounter the piece through a textual transcription.

I decided to enlist some help. What if I shared the song with someone else so that I could hear it outside of my own voice? How might that open up possibilities for interpreting the piece? I teach a singing class to young women between the ages of seven and fourteen at a non-profit children’s theatre. Every once in a while I throw a strange tune at the students and let them in on my research. I explained that the song was a lullaby. It was originally sung by an African-American woman in Georgia, probably just after the era of slavery and it had been passed from woman to child. Though some of the students in my class read music, we learn by ear. I handed out copies of the song made directly from the book, but without the title or headnote.

Ah yah, tair um bam, boo wah, Kee lay zee day, Nic o lay, mah lun dee.

Nico lay ah poot a way, Nic o lay ah wah mee—

Ah yah, tair um bam boo wah, Kee lay zee day, Nic o lav. mah lun dee.

Before learning to sing it, we talked about what the words might mean. They laughed hard at “poot a way” … and not just because it sounds like a reference to flatulence, but because several of the young women are native Spanish speakers and one of the syllable combinations sounds like a particularly bad curse word in that language. The girls were fixated on “bam, boo” possibly meaning something about bamboo trees and a forest. We all decided that “Wah me” sounds like “Why me?”

Though it was impossible to locate a fixed meaning, thinking through the possibilities allowed us to imagine certain emotional scenarios that would help us musically express the song. My students ended up interpreting the piece much as I had, but they added their own touches.

The students sing the lullaby.

We made this recording soon after learning the song. At first, I hesitated to share it because the singers don’t perform particularly well. However, I think that some of what we might hear as ‘errors’ in terms of technique open up possibilities for new interpretations and can teach us quite a bit about the process of oral circulation. In the recording, the young singers are more playful with pitch than I am and because I have no verification that Sandburg’s transcription is accurate by any means, it’s fun to imagine that by failing to execute the lyrics or music perfectly, they may not be any more ‘incorrect’ than his version.

After all, wouldn’t a song like this have changed from woman to child, from day to day, from generation to generation? I love the way the girls’ pitch slides throughout the piece, as if their voices are determined to find a more comfortable key. They reach unison on certain notes and stray and wander on others.

This rough performance exemplifies music as a process: how a single piece of music can evolve as it circulates across voices and time. It is, in a way, a sonic illustration of musical variation, helping us to perceive how a tune can exist in various forms and still be considered a single entity. Also, by encountering the song through a multi-vocal recording, we can lift it off the page and back into the realm of the vernacular. Though I don’t wish to overstate the distinction between the two modes or to romanticize the one over the other, my point is that the media through which we encounter music makes a strong impression on our understanding of it. Because I am interested in exploring vernacular music cultures historically, restoring transcriptions to aural performances is a useful way to de-privilege print and text in our efforts to hear the past.

Here is an example of one of the students, Nadia, performing the piece solo.

Nadia sings the lullaby solo.

By sharing the lullaby with a new generation of singers, I have been able to experience the song as far outside its textual representation as I can as a historical observer. Margaret Johnson’s story, Sandburg’s title and narration, and the transcription into sheet music all threatened to overpower the possibility that the song could speak its own history. Though I wanted to listen to the woman who initiated the chain of transmission that brought the piece to me, I continued to be distracted by the writing that accompanied it.

I felt persuaded that the song was a lullaby, for example, and because I myself shared the piece with children, I wanted to interpret the music and my encounter with it as something connected to childcare and a genre of music-making predominated by women. Maybe one can’t press a mute button on stereotypes. Now, having written this essay, I realize that by listening to the sounds themselves in the form of my students’ performances, I learned more than I anticipated about the nature of aural transmission and music transcription.

But what of the singer whose story I longed to uncover?

Though she remains distant and opaque to me, hidden among the silences of history and the words framing her performance in the book, her music is frequently in my ears and on my mind. It may be that knowing her song means simply that, to know it. Listening is often understood as a means to receive rather than perceive information. (“I hear you” and “I’m listening” come across a bit differently than “I see what you mean.”) By staging opportunities to listen to historical performances, we can mobilize both our fields of perception and reception. Emphasizing auditory culture also helps us to engage with historical actors who did not author their own narratives in print as subjects rather than as simple objects of history. The song, then, is not a portal into an understanding of a particular woman’s story, but an opportunity to witness something that her voice made known. Rather than repackaging the music and its creator like Sandburg did, this time, I’d rather just listen.

I wish to thank the young women in my singing class for sharing their voices with me and for challenging my assumptions. I dedicate this essay to them and to the memory of the woman who first sang this song.

The author would like to acknowledge Whitney Trettien, Darren Mueller, Ben Breen, and the Appendix editorial team for their insightful contributions to this essay.