Solitude and Sandaya: The Strange History of Pianos in Burma

On a quiet evening in March 1988, Aung San Suu Kyi’s telephone rang. The Burmese expatriate was reading quietly with her husband at her home in Oxford, England, when she learned of her mother’s stroke. Two days later, she left her family in the UK and returned to Burma for her first extended visit since the age of fourteen. In her thirty-year absence, little had changed politically. Although the country would soon rename itself Myanmar, it was still governed by the same brutal military dictatorship, and internal conflict had been raging for decades. Today, that dictatorship is the world’s oldest, and Burma’s civil war is the world’s longest-lasting.

Aung San Suu Kyi did not intend to dedicate her life to helping the people of her home country when she returned to care for her ailing mother, but events soon spun out of her control. Her father was a national hero who had helped free Burma from colonial rule. A national memorial day commemorates his assassination, and thousands of student protesters carried his portrait as they were gunned down in 1988. Her lineage and the timing of her visit made Aung San Suu Kyi an ideal, if accidental, leader. She soon relented to the call of her compatriots and helped form the National League for Democracy (NLD). In July 1989, the army arrested key members of the new party and confined Aung San Suu Kyi to her home, spared imprisonment only because of her public stature. She continued to lead, launching a twelve-day hunger strike to ensure humane treatment of her supporters. Her party, the NLD, won the election of 1990 in a landslide victory, but the results were ignored. Aung San Suu Kyi remained under house arrest for most of the next twenty years.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s husband, Michael Aris, was permitted to travel from Oxford to visit his wife only five times after her initial arrest. He was denied a visa during his two years fighting terminal cancer because the army hoped Aung San Suu Kyi might finally then be compelled to leave Burma. She remained in her home, a prisoner of conscience. Soon after one Christmas-time visit, Aris wrote of his wife’s “strict regime of exercise, study, and piano.”

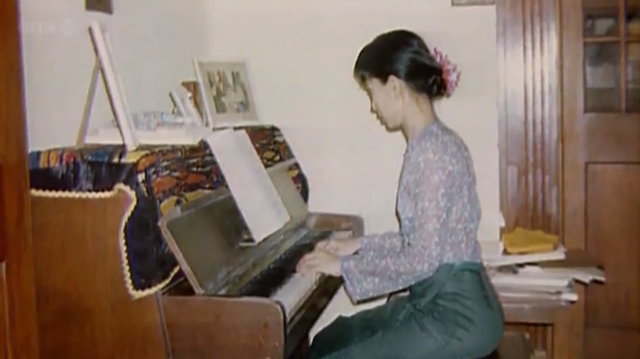

Aung San Suu Kyi at the piano, screenshot from the the BBC 2 documentary Aung San Suu Kyi: The Choice (2012).

The poignancy of Aung San Suu Kyi playing piano in rebellious isolation was not lost on the world. Concerned supporters reportedly snuck within earshot for assurance she was still alive. Famous Europeans who publicized her struggle sympathized with her as musicians. U2 called her “a singing bird in an open cage.” Annie Lennox tried to send her a new piano. The top prize in the Leeds International Piano Competition was recently renamed the Daw Aun Suu Kyi Gold Medal for its fiftieth anniversary.

Musicians have succeeded in turning the image of her piano, sometimes singing proudly, sometimes rendered unplayable due to the unavailability of qualified technicians, into an emblem of Aung San Suu Kyi. Most of the world had long ago already deemed her the principal, if not the only, symbol of opposition to Myanmar’s dictatorship. In a piece from November 2012, the Los Angeles Times connects the dots, calling the piano itself “a symbol of Myanmar’s struggle for democracy.” This web of symbolism is easy for Westerners to appreciate. The movement for democracy in Burma and the instrument played by its most famous champion were both neglected and silenced under tyranny.

The untold dimension of this relationship is that pianos, often in less-than-perfect condition, have been a fixture of Burmese culture since well before Aung San Suu Kyi. A century earlier, pianos were dragged through forests by elephants and ravaged by termites in the tropical heat. Improbably, this Western instrument became a focal point for musical innovation and cultural hybridity in Burma long before it found international prominence as a symbol of Burmese liberation.

Before Burma was annexed by the British Empire, the music of the royal courts and the homes of the elite was similar to the musical accompaniment of outdoor festivals in the countryside. Ensembles in different settings used different instruments, but the music was based on the same collection of traditional melodies, the Mahagita. There was certainly a division between “classical” and “popular” styles, but it was never as stark as the parallel split in Western music after the Christian church began to consciously distance its music from folk music a millennium ago.

The penultimate Burmese king, Mindon Min, was a reformer whose reign from 1853 to 1878 enjoyed relative prosperity, thanks in part to high cotton prices resulting from the American Civil War. He learned of the piano from a minister he had sent to England to report on Western technology. When an instrument was delivered to him as a present from the Italian ambassador, he reportedly ordered his court musicians to figure out how to translate the music of the Mahagita into something that could be played on the piano. These Burmese may have had some previous familiarity with piano music, but it would seem that little concession was made to established Western technique. Instead, the musicians used their existing pattela and pat waing music as a reference.

Burmese musicians playing traditional instruments, including the pattela, at the Shwedagon Pagoda in 1895. Wikimedia Commons

Burmese musicians enthusiastically adopted the new instrument, which they called sandaya—but on their own terms. Kit Young explains how “a completely unique technique of interlocked fingering with both hands extending a single melodic line allowed for agogic embellishment.” She describes its sound as “fleeting grace notes in syncopated spirals around a steady underlying beat.” The most obvious and seemingly natural element of all Western piano writing was absent from early sandaya music: the right hand playing high notes and the left hand playing low notes. Hundreds of years of Western music featured melody in the right hand with the left hand providing supporting harmonies. Burmese musicians made no such distinction. The two basic components of their music, melody and embellishment of the melody, were equally distributed between the two hands across the whole range of the keyboard.

This method allowed for very rapid playing, and the more notes per second that could be played, the more complex embellishments could become. By the 1930s, extremely fast, florid ornamentation adapted from the style of virtuoso saung gauk (a type of harp) players was expected in all Burmese music. The piano made such figuration easy. A 1980s recording of the famous U Ko Ko playing “When The Saints Go Marching In” demonstrates the distinctiveness of typically elaborate Burmese ornamentation: the tune is almost unrecognizable to Western ears. It is as different from classical or jazz piano playing as those styles are from each other.

U Ko Ko performing “When The Saints Go Marching In”

Sandaya was born in the courts of the last two Burmese kings, but it blossomed in the cinemas that popped up all around the country in the first half of the twentieth century. The burgeoning silent film industry, offering both movies made in the West and ones made at home in Burma, required a steady stream of experienced pianists to accompany them. Burmese music was ideally suited to the task. Listeners already associated different melodic themes and playing styles with corresponding dramatic concepts (such as love scenes, battles, and scenes with horses). The songs of the Mahagita had been used to accompany traditional theater for centuries, creating a musical language that was richly descriptive. Robert Garfias writes of the silent film era, “Pianists were expected to ‘explain’ and highlight the actions on the screen with the appropriate traditional Burmese music.”

Although the piano was not native to Burma, it became a naturalized citizen within a few decades of its arrival. The early sandaya players not only invented their own technique based on existing percussion instruments, but also retuned their pianos to more closely resemble the scales of Burmese instruments. In Rangoon circa 1925, despite the British colonial presence, a person could sit in an entirely Burmese audience, watch a film made in Burma, and listen to music from Burma played by a Burmese musician in a Burmese style and tuning. The presence of a piano made it no less an authentically Burmese experience then the presence of a film projector. It could be argued that their music was Westernized by the piano. But it is more appropriate to see the piano’s arrival as giving birth to something entirely new: a distinctly Burmese tradition based on a foreign instrument.

When Western listeners hear “world music” played on piano, it is almost always the result of a composer incorporating elements of other musical cultures into the fabric of an established Western style. Folk melodies are quoted in sonatas; drones are imitated for meditative, New Age effects. The evolution of sandaya in the twentieth century essentially represents the reverse of that process. The piano was a Burmese instrument that gradually became a vehicle for experiments with Western tonal language, structures, and fingerings. To many, those foreign ideas were an exciting addition to sandaya music; to others, they diluted its uniqueness.

One of the most fundamental shifts in the sound of piano in Burma concerned its tuning. The Cinema de Paris in Rangoon adopted a policy of showing Western films and Burmese films in alternating two-week spans. Two separate pianists were employed to accompany them, a man named Ko Oo Kah handling the locally-made films, and an Anglo-Indian named Mr. Robbins playing for the Western films. Once a month Mr. Robbins would come in, complain about how out-of-tune the piano was, and adjust it to the Western equal-temperament system.

Ko Oo Kah disagreed. The piano was retuned back and forth so many times that the action of the white keys on the instrument was eventually rendered unfixable, leaving Ko Oo Kah to take hammers and screws from the black keys and rebuild the instrument such that only his music would be performable.

Burmese aesthetic convention won that particular battle, but with regard to tuning, there can be no doubt it has lost the war. Today, the original intonation of Burmese piano is difficult to find. According to Kit Young, “U Ko Ko used to play with tunings on his midi-electric keyboard, but for performances in studios and theaters, he stuck to equal-tempered tuning.” There are a few older sandaya recordings available in the West that sound vaguely out-of-tune to our ears, but they are more likely the result of heat warping the instrument than documents of a true equidistant heptatonic Burmese scale. The piano in Myanmar still speaks Burmese, but its original accent has been lost.

In 2011, the isolationist Burmese military demonstrated that they were not immune to political pressure and shifting internal attitudes when they released Aung San Suu Kyi (likely permanently) and began a series of limited reforms. It is impossible to know the exact motivations of those new policies, but it is clear that some kind of change is happening behind the curtain. Aung San Suu Kyi was silenced during her many years of house arrest, but she was not entirely isolated. She likes to say that her daily habit of listening to the radio probably kept her better informed than most people not under house arrest, and she has emerged confident in the company of world leaders.

It is helpful to remember these varieties of isolation when considering the history of sandaya. As Burmese musicians became exposed to Western sounds via films and radio, they produced a variety of syncretic, experimental styles. Isolation did not prevent this music from being performed and recorded, but it did prevent anyone in the West from hearing it. As Timothy Rice explains, “The reclusive policies of the ruling dictatorship have retarded access to, and study, of Burmese music, and to a significant degree they have limited cultural and commercial exchange…” Only two discs devoted to sandaya have ever been available in America and Europe; one is long out of print, and both are flawed.

The decision of many Western countries to impose trade sanctions on Myanmar, suspend aid, and boycott tourism may have pressured the dictatorship to move towards democratic reform, but it also may have impeded that progress to some degree. In either case, dismissing the country as an off-limits “outpost of tyranny” certainly has done little to facilitate cultural understanding. The obscurity of sandaya is the result of internal repression, but also of the West’s own reluctance to engage with Burmese music directly.

The two discs of Burmese piano available in the United States feature Burmese musicians, but they are recorded, mixed, mastered, and edited by Westerners, and marketed towards a Western audience. Lacking sufficient reverb and traditional bell and clapper accompaniments, they do not represent how most Burmese musicians expect their performances to be heard. Sandaya: The Spellbinding Piano of Burma, released by Shanachie Records, almost appears to be presenting the music as an ancient artifact, preserved under glass from a time before the military coup. Packaging sandaya as the product of a happier Burmese past in a clean, uncluttered recording makes for a more palatable (and profitable) disc for international audiences, but it shields us from the reality of a much messier, more varied, more interesting century of music.

More recently, the Gitameit Music Center in Yangon has digitized 3,500 sides of 78s and recorded interviews with older performers. The project needs help to continue, but when it becomes available online it will be most listeners’ first opportunity to hear sandaya unmediated by outsiders. At present, the only commercially available examples of sandaya actually produced by and for Burmese people can be found on compilations released by the record label Sublime Frequencies—but they are still compilation cuts, not original records. The Sublime Frequencies discs will soon by joined by Longing for the Past, a 4 CD collection of Southeast Asian 78s to be released on Dust-to-Digital, which will include two tracks of sandaya playing.

Myanmar is opening up, and Aung San Suu Kyi is free. She is now more than an advocate for democracy and human rights: she is an active politician. As the West alternately celebrates her release and struggles to make sense of her puzzling stance on certain issues of ethnic violence, we might remember sandaya and the hybrid culture it represents. The piano in Burma was more than a sentimental symbol or an exotic museum piece: it was an important player in a tumultuously creative century of Burmese music. “What the Burmese have done with a piano,” write the compilers of Princess Nicotine, “is so precise in the adaptation to their existing form and melody that one would think they invented it.” Yet this was not the case. Perhaps the hybrid origins of the Burmese piano and sandaya might point a way forward toward a Myanmar that forges connections with the West even as it retains a Burmese soul.

The author would like to thank Kit Young for her kind assistance.